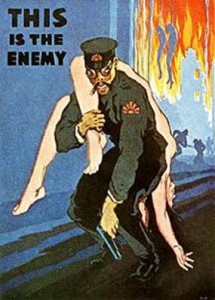

Because Japan chose to invade several colonial outposts of the West, the war in the Pacific laid bare the inherent racism of the colonial structure. In the United States and Britain, the Japanese were more hated than the Germans. The race card was played to the hilt through a variety of Allied propaganda methods. Spurred on by vocal American trade protectionists wary of inexpensive Japanese goods, the campaign would eventually help cajole the American public into a pro-war, anti-Japan position. By 1938, as historian Michael C.C. Adams writes, polls showed more Americans favored military aid to China than to Britain or France. Even more so than the Third Reich, Japan was the U.S. villain of choice.

“Periodicals that regularly featured accounts of Japanese atrocities,” says author John Dower, “gave negligible coverage to the genocide of the Jews, and the Holocaust was not even mentioned in the ‘Why We Fight’ [film] series Frank Capra directed for the U.S. Army.”

The Japanese soldiers (and, for that matter, all Japanese) were commonly referred to and depicted as subhuman: insects, monkeys, apes, rodents, or simply barbarians that must be wiped out or exterminated. The American Legion Magazine‘s cartoon of monkeys in a zoo who had posted a sign reading, “Any similarity between us and the Japs is purely coincidental” was typical. A U.S. Army poll in 1943 found that roughly half of all GIs believed it would be necessary to kill every Japanese on earth before peace could be achieved. Their superiors in Washington appeared to agree. By December 1943, as Adams notes, there were more troops and equipment in the Pacific than in Europe, and it has been estimated that 1,589 artillery rounds were fired to kill each Japanese soldier.

The Japanese soldiers (and, for that matter, all Japanese) were commonly referred to and depicted as subhuman: insects, monkeys, apes, rodents, or simply barbarians that must be wiped out or exterminated. The American Legion Magazine‘s cartoon of monkeys in a zoo who had posted a sign reading, “Any similarity between us and the Japs is purely coincidental” was typical. A U.S. Army poll in 1943 found that roughly half of all GIs believed it would be necessary to kill every Japanese on earth before peace could be achieved. Their superiors in Washington appeared to agree. By December 1943, as Adams notes, there were more troops and equipment in the Pacific than in Europe, and it has been estimated that 1,589 artillery rounds were fired to kill each Japanese soldier.

As a December 1945 Fortune poll revealed, American feelings for the Japanese did not soften after the war. Nearly twenty-three percent of those questioned wished the U.S. could have dropped “many more [atomic bombs] before the Japanese had a chance to surrender.”

This virulent brand of genocidal hatred was the end result of a massive public relations effort to demonize the enemy in the Pacific and thereby justify anything in the name of victory. A fine example could be found in the New York Times when the newspaper of record ran an ad that showed a flamethrower being used to kill Japanese, bearing the headline: “Clearing Out a Rats’ Nest.”

With generals like the Australian Sir Thomas Blamey informing his troops that, “Beneath the thin veneer of a few generations of civilization, [the Japanese] is a subhuman beast,” the feeding frenzy of ignorance and race antagonism culminated in the Allied forces acting our their predetermined role in a self-fulfilling prophecy. If a subhuman will fight to the death like an animal, those fighting on the side of good were simply left with no alternative but to slaughter them unmercifully. Since Japanese soldiers were under pressure not to surrender and were often killed when they did, this became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

General Blamey later told the New York Times: “Fighting Japs is not like fighting normal human beings. The Jap is a little barbarian. . . . We are not dealing with humans as we know them. We are dealing with something primitive. Our troops have the right view of the Japs. They regard them as vermin.”

This insight was quoted by the Times on the front page.

Eugene B. Sledge, author of With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, wrote of his comrades “harvesting gold teeth” from the enemy dead. In Okinawa, Sledge witnessed, “the most repulsive thing I ever saw an American do in the war” — when a Marine officer stood over a Japanese corpse and urinated into its mouth.

There was no shortage of horror stories about Japanese atrocities to fuel such animosity, and a large part of them were true. Of the 235,473 U.S. and U.K. prisoners reported captured by Germany and Italy combined, only 4 percent (9,348) died while an astonishing 27 percent of Japan’s Anglo-American POWs (35,756 of 132,134) did not survive. Indeed, with the Rape of Nanking, the Bataan Death March, and incidents such as an ambushing of Marines on Guadalcanal by Japanese soldiers pretending to surrender, the litany of Japanese war crimes did not need much embellishment to stir up Allied fury. The ensuing behavior of the men fighting the Japanese in the Pacific (and those rooting for them back home) was merely the anticipated outcome of a deadly campaign of manipulation and propaganda against an enemy, which often played right into those fears. The results, however predictable, are no less appalling.

“In April 1943,” Dower reports, “the Baltimore Sun ran a story about a local mother who had petitioned authorities to permit her son to mail her an ear he had cut off a Japanese soldier in the South Pacific. She wished to nail it to her front door for all to see.”

In a 1943 issue of Leatherneck, the Marine monthly, a photo of Japanese corpses was run above the caption: “GOOD JAPS are dead Japs.” The March 15, 1943 issue of Time followed suit by reporting without criticism about a “low-flying fighter turning lifeboats towed by motor barges and packed with Jap survivors, into bloody sieves.”

Where is such behavior spawned? One breeding ground is boot camp. Consider this U.S. Marine Corps boot camp chant:

“Rape the town and kill the people, that’s the thing we love to do! Rape the town and kill the people, that’s the only thing to do! Watch the kiddies scream and shout, rape the town and kill the people, that’s the thing we love to do!”

Perhaps Edgar L. Jones, a former war correspondent in the Pacific, put it best when he asked in the February 1946 Atlantic Monthly, “What kind of war do civilians suppose we fought anyway? We shot prisoners in cold blood, wiped out hospitals, strafed lifeboats, killed or mistreated enemy civilians, finished off the enemy wounded, tossed the dying into a hole with the dead, and in the Pacific boiled flesh off enemy skulls to make table ornaments for sweethearts, or carved their bones into letter openers.”

The “official” word was equally as repugnant: Elliot Roosevelt, the

president’s son and confidant, told Henry Wallace in 1945 that America should bomb Japan “until we have destroyed about half the Japanese civilian population.” Paul V. McNutt, chairman of the War Manpower Commission, went a little further when he advocated to a public audience in April 1945 the “extermination of the Japanese in toto.” Secretary of War Henry Stimson concurred, stating that, “to get on with Japan, one had to treat her rough, unlike other countries.” That these sentiments were often translated into action is borne out in the reality that the U.S. bombers killed four to five times as many civilians in the last five months of the Pacific war than in three years of Allied bombing in Europe combined. And then there was the man who’d eventually give the order to drop atomic bombs on Japanese civilians.

“We have used [the bomb] against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare,” Harry Truman later explained, thus justifying his decision to nuke a people that he termed “savages, ruthless, merciless, and fanatic.”

Such rhetoric and the comportment it spawned were encouraged, according to Dower, by three basic rationalizations. Firstly, the “suicide psychology” involved the myth that, since the fanatical Japanese would rather die than surrender, they “invited destruction.” The second rationalization had its roots in the First World War and the treaty that ended it. “Anything less than a thoroughgoing defeat” would be “incomplete” and invite the Japanese to use peace as a chance to prepare for war . . . as the Germans did between the

two world wars. Finally, the “psychological purge” evoked the concept of the Japanese requiring castigation in the form of “great destruction and suffering.” As Alger Hiss explained at the time, “[Japan’s] entire national psychology [must] be radically modified.”

The inherently racist premises behind these three rationalizations eerily evoke the justifications often proffered for the extermination of Native Americans or the enslavement of Africans. Two decades after the end of the “Good War,” the U.S. was still getting mileage from what became known as the “mere gook rule.”

“During the Vietnam War,” writes Edward S. Herman, “it was reported that cynical U.S. lawyers working in that country had coined the phrase ‘mere gook rule’ to describe the very lenient treatment given to U.S. military personnel who killed Vietnamese civilians.” This policy held sway right on through various American intervention in Latin America, the “humanitarian” effort in Somalia, and, of course, the Gulf War and Kosovo. Herman sums up the philosophy as follows: “If our opponents do not submit and we are obliged to blow them up, clearly it is their responsibility.”

Of course, for the men doing the actual fighting, it essentially comes down to the most basic of racist tenets. In order to inflict inhumane punishment, it is necessary to convince oneself that the enemy is not fully human. Once that belief is established, slavery, genocide, and the boiling of flesh off of Japanese skulls to be saved as souvenirs have all the justification they will ever need.

Mickey Z. is the author of several books including the soon-to-be-released There Is No Good War: The Myths of World War II (Vox Pop) and 50 American Revolutions You’re Not Supposed to Know: Reclaiming American Patriotism (Disinformation Books). This essay was excerpted from There Is No Good War. He can be found on the Web at <http://www.mickeyz.net>.