Paul LeBlanc |

Paul LeBlanc is what I have called an “organic intellectual,” a scholar and activist who has risen directly out of the working class. Paul is the author of many books, including A Short History of the U.S. Working Class (Humanity Books, 1999) and Black Liberation and the American Dream (Humanity Books 2003), and is an internationally known and respected historian of the life and works of Rosa Luxemburg. Paul has been active all his adult life in antiwar, antiracist, and socialist movements. He is currently an Associate Professor of History and Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at La Roche College in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This interview was conducted by email in August 2006.

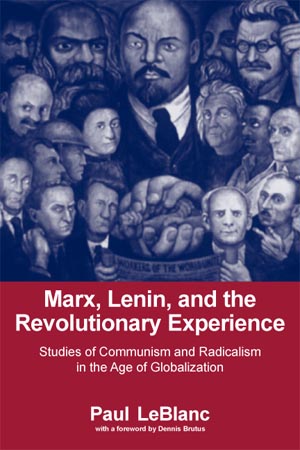

Michael Yates (MY): Paul, tell us how you came to write Marx, Lenin, and the Revolutionary Experience?

MARX, LENIN, AND THE REVOLUTIONARY EXPERIENCE: Studies of Communism and Radicalism in an Age of Globalization by Paul LeBlanc BUY THIS BOOK |

Paul Le Blanc (PLB): I started writing it almost eight years ago, and it went through about twelve revisions. It was initially a follow-up to a book I wrote in the late 1980s, Lenin and the Revolutionary Party. Originally I called this one “What’s Wrong With Lenin?” and thought of it as a short work that would look seriously at common critiques of this controversial but (for serious revolutionaries) essential figure. I wanted especially to reach out to younger activists to share information that I thought would be helpful to them in figuring out “what is to be done” to make the world a better place. It seemed to me that these activists should look critically at the Leninist tradition, but that they should not accept the dismissive or trash-and-bash attitude toward Lenin common among conservatives and liberals but also on so much of the Left.

As I kept working on the book, I revised it and reworked it under the impact of reactions from various people (political comrades, colleagues, students, and others), but influenced as well by all that was happening in the world around me, and also by my own evolving thought and experience in that changing world. In some ways I am a different person than the one who began writing this book a decade ago. It evolved in the way that some authors describe novels evolving: the characters take on a life of their own, forcing the author to go places that he or she had not imagined going, taking what — for the author — are startling turns. It was as if various people that I knew, through my life and through my reading and research, took hold of what was happening as I labored to tell the stories that are part of this book.

Paul LeBlanc Lectures on Rosa Luxemburg at Wuhan University. Photo by Wu Xin Wei.

Paul LeBlanc Surrounded by Students at Wuhan University. Photo by Wu Xin Wei.

The original purpose is very much there — and yet the book has broadened dramatically. Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg have insisted on a greater presence than I had intended, and so have the anarchists. People who were members of the mainstream of the Communist movement in the time of Stalin have insisted on being taken more seriously, and so have people who were part of that movement but who went on to become anti-Communists and were even propelled to the political right. (How on earth can someone who believed in making the world a better place, someone who committed his or her life to that, have ended up on the other side of the barricades? I felt pushed into wrestling with that question, into taking such people seriously, even as I disagreed with them on so many things.) The biggest surprise, though, was around religion — and the influence of Martin Luther King, Jr., A. J. Muste, Paul Tillich, Simone Weil, Dorothy Day, Pope John XXIII, and others are very much in this book.

It amazes me how the classical Marxist work of Karl Kautsky on early Christianity, as well as the Irish-American revolutionary James Larkin‘s pugnacious blending of Marx and Christ, intersects with the Social Gospel strictures of Walter Rauschenbusch, the radical “Christian realist” interventions of Reinhold Niebuhr, the “black church” radicalism of Howard Thurman and James Cone, the liberationist challenges of Leonardo Boff and Dorothee Soelle, the theological reflections of Marcus Borg, groundbreaking scholarship John Dominic Crossan, and even (with all his contradictions) the social thought of Pope John Paul II. The revolutionary novelist Maxim Gorky and the Bolshevik Commissar of Culture Anatoly Lunacharsky are part of this mix, as is the great U.S. literary critic F. O. Matthiessen (one of the earliest and most substantial supporters of Monthly Review, a Christian, victim of homophobia and McCarthyism, a suicide).

The book engages with the “red decade” of the 1930s, and with the 1940s aftermath (in which Monthly Review‘s founders Paul Sweezy and Leo Huberman played such an important role), the decades in which some of my favorite relatives flourished as political activists, but also with the 1950s — which such idiosyncratic people as Hannah Arendt, Harry Braverman, C. L. R. James, C. Wright Mills, Nora Sayre, and others (each in their own way) helped to define. Then came the 1960s — with the upsurge of the civil rights movement, the opposition to the U.S. war in Vietnam, and the “new left” in which I was involved.

And then there are late-1960s and early-1970s theorizations of leftist philosophes Herbert Marcuse and Henri Lefebvre, which at the time did not conform to my Trotskyist inclinations, but whose insights have corresponded to the global justice movement of recent years and therefore caused me to rethink some of my own notions.

So my feeling was that these elements needed to be part of the book. I felt that there was a need for connecting with the generations preceding me, and for connecting them and my own generation with the generations — including our children and grandchildren, and their children — evolving after me. I think it’s so important for the rising and future layers of activists to have a sense of the many, many kindred spirits who came before, and to learn something from their ideas and experiences.

There was something else that impacted on the development of the book. There seems to have been a major push in this country, especially since the end of the Cold War, to demonize the Communist tradition, globally and in the United States, as simply a wicked and murderous totalitarian conspiracy. There’s the translation of The Black Book on Communism, books like John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr’s In Denial, the sad recent works of David Horowitz and Ronald Radosh, not to mention such stuff as Ann Coulter’s Treason. I believe the Communist tradition must be understood critically, and aspects of it — particularly those that have been identified with the term “Stalinism” — must be utterly rejected by serious political people. It is also important to critically assess Lenin. But the wholesale demonization blocks serious political thought (and in some cases is meant to do just that).

Especially in the dangerous times in which we live now, we can’t allow that to happen. There have been the intensifying global problems culminating in the terrorist assaults of 9/11, in the drive toward Empire embroiling us in the disastrous Iraq war, in the growth and intensification of poverty and hunger and disease, in the catastrophic erosion of the ecological balance of our world. People have to be able to think knowledgeably and clearly about the realities of the past and possibilities of the future. A key aspect of this means cutting across the demonization of the Communist tradition and, instead, critically comprehending it and being able to make use of elements from it that have been positive and can help serious political people both to understand and to change the world.

MY: You argue in your book that the influence of Marx and Lenin is much greater than might normally be supposed. For example, the civil rights movement. Liberation theology, etc. have been influenced by them. Can you tell us something about this?

PLB: I think there is no question about this. Marx and Lenin — their concerns, insights, conceptualizations — powerfully influenced, for example, religious thinkers who were incredibly influential in the United States long before liberation theology came into being. You see this in Rauschenbusch, Niebuhr, Tillich, and others whom I talk about in my book. In part because of this influence, and also very much because of the 1930s labor radicalization (through Communists, Socialists, Trotskyists, Lovestoneites, Musteites and others), their ideas permeated the thinking of those who initiated and helped lead the early civil rights movement.

These folks were not necessarily Marxists or Leninists (though some were), but they were influenced by the concerns, insights, and conceptualizations of Marx and Lenin. This is true not only of people like Carl and Anne Braden of the Southern Conference Educational Fund, or Myles Horton and those who created the Highlander Folk School that was important in the development of so many activists (such as Rosa Parks, Septima Clark, Andrew Young, etc.). There were also people such as A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Ella Baker who had earlier been shaped, in part, by Marxist influences. This is also true, though to a somewhat lesser extent (and largely through his engagement, I think, with Rauschenbusch and Niebuhr), of Martin Luther King, Jr., who seems to have been a conscious socialist since the late 1940s. Many of the young activists who became part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were influenced not only by the people I’ve just mentioned but by others with similar orientations (as well as such publications as Monthly Review) as they helped organize the struggles that transformed the South and the entire country.

Similar things can be said, of course, about the labor movement, and not only in the “red decade” of the 1930s with the well-documented involvement of the Left in the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. If you take a look at the early organizers of the American Federation of Labor in the 1880s, you see a strong Marxist influence — which was written into the class-struggle preamble of the AFL’s original constitution (which was only junked when the AFL and CIO merged in 1955). As Alan Wald, Paul Buhle, Michael Denning, and others have shown, the influence of Marx, Lenin, and other revolutionaries has also soaked into U.S. culture (including popular culture) — among writers, artists, intellectuals, filmmakers, actors and actresses, cartoonists, in television, in our music, and so on.

Of course, right-wingers have often sought to make much of this, attacking “communistic influences” that they claim subvert the “American way of life.” But they should be careful. As I show in my book, conservative thought in the United States has also been “contaminated” by the influence of Marx and Lenin (particularly through such people as James Burnham, Frank Meyer, Will Herberg, Whittaker Chambers, Irving Kristol and other ex-leftists — with a twist, to be sure).

MY: Do you see any contradictions between the secularism of Marx and Lenin and the religiosity of so many progressive change activists?

PLB: Yes and no. Or to put it differently, it depends (as always) on what we mean by such things. The word “religion” has the connotation for many secular leftists of being equivalent to superstition, opposition to science, authoritarian moralistic rules, drawing people away from struggles for social justice today because they are promised a “pie in the sky” afterlife tomorrow. It is also seen as being intertwined with existing power structures. It is certainly the case that organized religion inclined very much in the direction of being pillars of a very reactionary status quo in the specific national cultures which Marx and Lenin experienced. Such “religiosity” is certainly in absolute contradiction to the orientation of Marx and Lenin, and they bluntly said so.

On the other hand, both Marx and Lenin expressed respect for religious revolutionaries who were prepared to challenge the powers-that-be and to help mobilize the poor, the exploited and the oppressed in struggles for social justice. Secular revolutionaries certainly have much more in common with religious revolutionaries than they do with secular opponents of revolution. My friend, the late Marxist literary critic Paul Siegel, tried to get at this by dedicating his critique of world religions, The Meek and the Militant (which has just been republished by Haymarket Books) to Thomas Münzer and Thomas Paine. Münzer was a revolutionary Christian leader and martyr during the Reformation and Peasant War in Germany, and Paine was a hero of the American and French revolutions and also an uncompromising critic of organized religion.

Teddy Roosevelt (who blended his own religiosity with the commitment to establish an American Empire) once called Paine “a filthy little atheist” — but actually, when you read Paine’s no-holds-barred assault on established religion, The Age of Reason, you find that he is not an atheist at all. He passionately believes in God, which he defines as the First Cause of all things — but his God is not a cranky tyrant sitting up in Heaven, but instead a force that is inseparable from the natural sciences, from a global embrace of all humanity, and from a deep moral sense that leads to struggles “to do good” for human freedom, democracy and social justice. There are some contemporary religious thinkers and activists who have an orientation — including a conception of God — very much like that of Tom Paine and who are opponents of the kind of imperial religiosity represented by Teddy Roosevelt and his modern-day counterparts.

Religion can be a way of giving simplistic answers to complex and troubling questions, as a way of providing reassuring, dogmatic certainties in order to explain away unpleasant realities, as a way of limiting and blocking critical thinking and preventing openness to those who are different. It can be, in this form, a powerful force for tyranny and intolerance, for hurtful and sometimes even murderous divisions among people, and for an enforced conformity to narrow conceptions of what it means to be human. Sometimes, when a secular Marxist accuses another secular Marxist of being dogmatic and sectarian and of having a “religious approach to Marxism,” what is meant is that the accused person is turning Marxism into an closed, intolerant, reassuring (as opposed to illuminating) mode of thought. This suggests that the same negative qualities which some people associate with religion are found among those who idolize secularism and science.

Religion is also a way of structuring one’s sense of connection with the rest of reality. It can involve a sense of awe and wonder over all that exists — the amazing mysteries of life and consciousness, one’s interrelationships with other people and other beings, one’s own sensuality and passion and creativity (in the broadest and deepest meaning of those words). These qualities, which I don’t see as being inconsistent with science or with the secularism of Marx and Lenin, are sometimes referred to as a sense of spirituality. I agree with Joel Kovel when he criticizes modern capitalism, in his interesting book History and Spirit, for a “de-spiritualization” that impoverishes the lives of so many people in our culture. Whatever labels one uses, these qualities can be structured and given coherence within the framework of the Marxist tradition and within the framework of one or another religious tradition. And I have come to the conclusion that it is possible to develop such structures — for example, an approach to Marxism and an approach to Judaism or Christianity or Islam or Buddhism — in ways that are very positive and very much in harmony with each other.

MY: What do you think are the most valuable lessons we can take from the radical ferment of the 1960s?

PLB: One of the most valuable lessons for me was that dramatic social and political change is possible — that minorities can be transformed into majorities, and power structures can often be forced to yield to the pressures created by popular movements. I saw this happen during the 1960s, and I helped make it happen, along with many other people of my generation.

It was interesting to see the transformation at the University of Pittsburgh, between 1965 and 1970. In 1965, the Student Government — with support of the Pitt News and the active participation of the fraternities and sororities — organized a large rally with about 1000 people in support of the U.S. war effort in Vietnam. Anti-war activists were definitely a marginal presence and were not permitted even to set up literature tables on campus. By 1970, in the wake of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State killings, the Student Government — with support from the Pitt News and the very active participation of fraternities and sororities — organized an anti-war strike that closed the campus down, in conjunction with student strikes throughout Pittsburgh that did the same thing. The anti-war movement drew thousands into the city’s streets, and no one would have considered trying to prevent activists from having their say or distributing their literature within the campus community.

This change was the product of several years of serious organizing — with one-on-one and small-group discussions, forums, mass leafleting, classes and conferences, marches and rallies — and it was happening not just on the campuses but in the larger community, and not just in Pittsburgh but throughout the country. And with inevitable fluctuations it continued beyond 1970 until the United States was finally out of Vietnam, in part because the protests and the creation of an anti-war majority limited the options of the war-makers. This organization of popular anti-war pressure (combined with similar organized pressures against racism, for women’s rights, and around other issues) both polarized “mainstream” politics and pushed it leftward. Many of us learned that politics is not the same thing as elections or politicians or government. We quickly came to understand that you can’t put your faith in such entities, that if we attempted to keep politics within those narrow frameworks, there would be no change. Only by moving outside the frameworks of such “traditional politics” would it be possible to build effective pressure — and on some questions, win majority support — for major changes.

Another thing I learned is that it is possible and sometimes necessary to engage in activity even when you don’t have a blueprint for where you want to go or how to get there. Sometimes it is necessary — if you have a moral sense and an understanding that something being done in society or by the government is just plain wrong — just to say that, to take a stand, to protest. Leading up to the protests, in the context of the protests, in the wake of the protests, it is possible and necessary to educate ourselves more about the realities, and to think through or debate possible goals and strategies — but it was important to be able to do something, to act, even as we were thinking through our politics. Along with this was the fact that we had to learn our own lessons. Sometimes older and more experienced political activists would offer warnings and suggestions and alternatives that made no sense to me initially — but in some cases they would make a lot more sense to me after experience challenged my earlier assumptions.

In some ways, the new left experience taught me a negative lesson. There was, in the early years of the new left, a sort of mystique about our “newness” and about our youth. We were inclined to believe that all the older left-wing organizations and ideologies had failed and were irrelevant, that such groups as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and SNCC represented the wave of the future and would somehow evolve qualitatively new ideologies that would enable us to change the world. And we came up against the inadequacy of our own half-formed and half-baked ideologies, and our inadequate organizational norms — in the midst of the youth radicalization exploding to mass proportions. There was a growing exasperation that the intensified struggles were not stopping the war or overcoming racism. I saw once easy-going and quietly reflective activists become, under such pressures, intense and dogmatic and sectarian — seeming to embrace caricatures of the worst of what some of us had earlier imagined the “old left” represented.

There were a few (as SDS blew apart) who went the way of the Weather Underground, others who evolved from the “new left” to one or another variant of Maoism in the “new Communist movement,” and others who went on to connect with one or another variant of the old left — whether the Social-Democratic reformism of Democratic Socialists of America, or the Stalin-influenced Marxism-Leninism of the old Communist Party, or the Trotskyism of the old Socialist Workers Party, or whatever. But there was something that had been valuable in the freshness and openness of the “new left,” I think, and it is a shame that this was lost.

Perhaps that was inevitable, but I think it is worth reaching to reclaim some of that for the left of today and tomorrow. Maybe more of that could have been held on to if less had been made of the old left/new left dichotomy, if there had been a greater symbiosis and interaction. Looking back on some of my own experience, it seems to me that in my experience as a new leftist I learned some old lessons (things you can find in Marx and Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin, Trotsky, Gramsci and others) having to do with the relationship between reform struggles and the revolutionary struggle, with the interplay between spontaneity and organization (and the importance of organization), the nature and importance of class, and questions of consciousness and culture. From the so-called “old left” side, I think Monthly Review was one of the few significant entities that tried to encourage the kind of symbiosis and interaction that I’m talking about. If there had been more of that, I think the U.S. Left would have been enriched even more by the new left contributions – and more of the distinctively new left freshness and openness might have survived.

MY: There has been a strong anarchist tendency in parts of the various contemporary social change movements. Do you see this as a problem?

PLB: I think in some ways it is a very good thing, and in some ways it is a problem. The anarchist tendency reminds me, in some ways, of the new left tendency of the 1960s. After the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the anarchist movement was a marginal element on the U.S. Left. For a young activist to become an anarchist today is — in some ways — to adopt a vibrantly “new” stance that clearly distances him or her from “old” and seemingly discredited elements associated with the Marxist-oriented Left (whether Social-Democratic, Communist, Trotskyist, or Maoist).

This can have a positive impact, I think, by helping to create an activist space for a rising layer of youthful radicals similar to what the new left represented. Also, the actual anarchist tradition historically contains a rich accumulation of insights, concepts, and ideas that can have a valuable impact. If we look back to the movement of Albert and Lucy Parsons, August Spies, and others — the International Working People’s Association (IWPA) of the 1880s — we find a wonderful blend of Marxist, libertarian, and labor-radical ideology that is worth retrieving and embracing. There are contributions from Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, Daniel Guerin, Paul Goodman, Noam Chomsky and others that deserve widespread circulation — to the extent that activists of today and tomorrow engage with them, the better off we will all be.

Of course, there are different variants of anarchism, and different currents and tendencies among today’s anarchists. Some tend to be in-grown and sectarian, creating their own little universe and dividing themselves off from other political currents, and in some cases from older activists in general. While this may have short-term benefits for those involved in such an orientation, I think it becomes a dead-end. There have also been some anarchists who are quite elitist and manipulative — and such things are problematical regardless of what political tendency they crop up in. One of the worst examples occurred in Genoa a few years back, when the irresponsible utilization of violent tactics by a militant minority did serious damage to the work of a broader international global justice coalition. That hardly defines the practice of all of today’s anarchists, but it certainly represents a problem.

A deeper problem that more than one anarchist theorist has commented on is the fact that there is such a diversity of distinctively anarchist political analyses, strategic and tactical orientations, organizational perspectives, and even basic principles, that it has been difficult to unify anarchists around a body of thought that would enable them to become a cohesive force capable of ushering in a better society. As a distinctive body of social analysis and strategic thinking, it was never able to offer anything approximating the coherence and relevance of Marxism. This is so even where the anarchists were capable of building relatively powerful movements — the Makhno movement during the Russian revolution and civil war, for example, as well as the anarcho-syndicalists of Spain in the 1930s.

It seems to me that the most promising anarchist model for us was in the Chicago labor movement of the 1880s, in the wing of the IWPA led by Spies and Parsons. There we find a bold and energetic blending of anarchist with Marxist ideas, a zestful creativity in reaching out to more and more sectors of the working class majority, and a thoughtful interweaving of reform struggles with revolutionary perspectives. Mistakes were certainly made (particularly due to the influence of more sectarian and ultra-left currents in different sectors of the IWPA) — and these mistakes made it possible for the authorities to break the IWPA and execute some of its leaders. It is important to avoid such mistakes, but a rebirth of the kind of anarchism represented by Spies and Parsons would be a very good thing.

MY: In the United States, the various Maoist groups that arose in the 1960s proved to be radical dead ends. Yet, as events in Nepal and parts of India have shown us, Maoism is alive and well. What is you assessment of Maoism?

PLB: My political background is one that is inconsistent with important aspects of Maoism, and my own experience with Maoism and Maoists is complex and contradictory. It seems to me that Max Elbaum’s account of Maoism in the United States, Revolution in the Air, provides a valuable account and critique of Maoism as it rose and fell within the U.S. Left — but aspects of that critique go beyond the idiosyncrasies of North American Maoism. I want to begin with the negatives, which I think Elbaum explains very well. Then I want to look at what strike me as positive qualities that can be found among some of those associated with the Maoist tradition.

Historically, Maoism has been closely intertwined with Stalinism. The fatal characteristics of Stalinism involve the glorification of a one-party dictatorship in which there is a cult around an absolutist leader, who claims an almost divine continuity between himself and the founders of Marxism (who are themselves portrayed as infallible) and whose wisdom cannot be questioned, let alone challenged. This naturally resulted in an uncritical, dogmatic approach to Marxism — which was opportunistically manipulated by the central Communist Party leaders to justify whatever policies they advanced, which were in some cases the opposite of those they had advanced only a short time before.

For Marx and Lenin, socialism involves, as the name implies, social ownership and control over the economic resources and institutions of society. This means the most radical form of “rule by the people” over the economy — that is, the most radical form of democracy. This is made clear in many of their writings — such as Marx’s Civil War in France and Lenin’s State and Revolution. For Stalin and Mao, socialism involved a collectivized and planned economy ruled over by a dictatorship in the name of the people, and often at the expense of the people. Stalin initiated a murderous “revolution from above” in the early 1930s which mobilized sectors of the population around top-down policies of rapid industrialization and forced collectivization of land, and also around a strident cultural conformism. Those who protested or got in the way — millions of people — were destroyed. Reflections of this can be found in much of what Mao did as well. In both cases, regardless of whatever gains might have been achieved, extreme damage was done to both the Soviet Union and China, as well as to the cause of socialism. Also, the foreign policies of both Stalin and Mao — despite significant amounts of anti-imperialist and class-struggle rhetoric during one or another moment — were also characterized, at other moments, by far-reaching deals and accommodations with imperialism and with the capitalist powers, often at the expense of working-class and liberation struggles around the world.

On the other hand, these negative qualities are not what drew millions of oppressed people and idealistic activists into the Communist movements influenced by Stalin or Mao. These millions were attracted by what appeared to be effective global movements against capitalist oppression and exploitation, in the interests of the laboring majorities of all countries, influenced by the powerful ideas of Marx and Lenin, punctuated by revolutionary victories. These movements were seen as pushing uncompromisingly in the direction of a better world in which there would be no more hunger and poverty and violence and tyranny, a world in which every person could have dignity, in which a decent and creative existence would be the common birthright of all humanity. When we analyze Maoism we cannot focus simply on the ideas or policies or individual qualities of Mao Zedong — we have to take into account the larger social reality of cadres and activists and supporters who were drawn into struggles around such goals and motivations, and the experiences accumulated through those struggles.

There are also certain specific qualities that can be identified with Maoism that go beyond such generalities. The fact that the young Mao was a thoughtful, idealistic Communist organizer working among oppressed peasants in the 1920s allowed him to develop insights about this sector of the population that was a vast majority of the people not only in China but throughout the world — insights that were beyond the experience of Marx and even Lenin. Related to this were innovations around the conceptualization of guerrilla warfare and the strategy of “people’s war.” Also related to this, given the dogmatic and opportunistic distortions of Marxism that developed under Stalin, was an inclination toward critical thought and a distinctive “Chinese approach to Marxism” that had to develop among Mao and his closest comrades as their policies of the 1930s diverged from the Stalinist orthodoxies being imposed on the world Communist movement (even as they sought to give lip service to those orthodoxies). It seems to me that some of this critical approach can be found, as well, in at least some of the differences between what happened in the USSR while Stalin was alive and what happened in the People’s Republic of China when Mao was alive.

Also, there were certain positive aspects of what was seen as Maoism — aspects that were in some ways illusory or were later compromised by Mao himself — that for a time drew many to the Maoist banner. Certainly during the 1960s there was a belief that Mao represented a far more consistent approach to anti-imperialism and class struggle than did the post-Stalin leadership of the USSR. There was also a belief that Mao represented a more consistent egalitarianism and involvement of the masses of the people in the struggle to create socialism after the Communist revolutionaries took power in China, and a greater rejection of bureaucracy and bureaucratic privilege, than had been the case in the USSR. Some of these beliefs about what Mao actually thought and did and represented involved major illusions about the actualities of such things as the incredibly destructive Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution — but such beliefs were definitely part of the Maoist movement throughout the world, nonetheless.

What this adds up to, I think, is that some of the most thoughtful and committed revolutionaries who were drawn to the banner of Maoism have been able — despite serious problems and contradictions — to remain revolutionaries, and to evolve into more informed, more effective, more consistent revolutionaries. This is the case, I think, particularly as they have remained true to the revolutionary ideals and commitments that originally brought them into the struggle. It is so particularly as they have remained connected to the ideas of Marx and Lenin (which have always been part of Maoism’s ideological mix and which contain essential anti-bodies to the Stalinist virus), and particularly as they have allowed themselves to reflect critically and self-critically on their own accumulating experiences and on what has happened in the world.

I certainly don’t know enough about Maoism in Nepal to offer anything of value in the form of either critical or positive analysis, but I have had an opportunity to connect and interact with activists influenced by Maoist thought in the United States, in Philippines, in India, and most recently in the People’s Republic of China. Among some of these activists, I have seen very positive qualities, and they seem to have moved significantly beyond the narrowness and destructiveness associated with Stalinism. I have found such comrades to be critical-minded people, open to working seriously with people from other political traditions, despite certain political differences that might remain. I am reminded of Lenin approvingly citing a remark of Trotsky’s, in the early 1920s, that debates within the Communist movement should involve mutual influence rather than mutual ostracism.

We live in an especially interesting time — highlighted for me recently when I had an opportunity to participate in an international Rosa Luxemburg conference at Wuhan University in China. Today in China, the official theoretical orthodoxy is called MMD — which means Marxism-Leninism/Mao Zedong Thought/Deng Xiaoping Theory. For many, this provides a justification for the Chinese economy’s far-reaching transition to becoming a component of global capitalism. For some who embrace the shift away from the destructiveness associated with Mao’s Cultural Revolution, however, there is a growing critical reaction to the destructiveness associated with the market economy. Some draw on Maoist conceptions to challenge this, and others also reach deeper into the Marxist tradition to make sense of the dramatically shifting realities in China and the world. At the conference, this involved divergent ways of understanding — in dialogue with international guests — the rich and potentially explosive ideas of Rosa Luxemburg.

MY: Paul, what do you think are the most important insights of Marx and Lenin in terms of transforming society in a revolutionary way?

PLB: A handful of slogans or an entire book could be offered as an answer — but a dense set of interrelated notions are what I will try to offer here in response to your challenging question. These include: capitalism making socialism possible and necessary; the centrality of the working class and working-class democracy in replacing capitalism with socialism; the importance of internationalism; and the necessity of organization.

One of the key insights offered by Marx and Lenin is that revolutionary change is possible and necessary. This is so in several ways. The nature of capitalism makes it both possible and necessary. The advance of technology and productivity — thanks to the dynamics of capitalist development — has drawn the different regions of our planet together and created a sufficient degree of social wealth, or economic surplus, to make possible a decent, creative, free existence and meaningful self-development for each and every person. Yet the dynamics of capitalist development (the accumulation process) are so destructive of human freedom and dignity that it is necessary to move to a different form of economic life.

The natural trend of capitalist development has been creating a working class majority in more and more sectors of the world, and the nature of the working class makes a socialist future both possible and necessary: possible because a majority class, essential to the functioning of capitalism, has the potential power to lay hold of the technology and resources of the economy to bring about a socialist future; necessary because the economic democracy of socialism is required to ensure the dignity, the freedom, and the survival of the working-class majority.

For both Marx and Lenin, then, we also see that socialism and democracy are inseparable: the very definition of socialism, for both of these revolutionaries, involves social ownership and democratic control over the technology and resources on which human life depends. Marx says in the Communist Manifesto that the working class must win the battle for democracy in order to take control of the economy. Lenin assents in various writings leading up to 1917 that the working class can make itself capable of bringing about socialism only by becoming the most consistent fighter for all forms of democracy and democratic rights.

Both of these comrades believe it will be possible to win a working-class majority to this perspective if revolutionaries develop a clear understanding of capitalist reality (which creates the possibility and necessity for socialism) and help others — especially among the growing working class — to understand that reality. But both of them also insist that an essential part of this process of creating a socialist majority among the working class will involve helping to organize the workers themselves around serious struggles to improve the condition of the working class (a better economic situation, an expansion of democratic rights, etc.). Not only will this result in life-giving improvements for the workers, but it will also give them a sense of their power and their ability to bring about change, and their organizational and class-struggle experience will enable them to struggle more effectively in the future. This will be necessary because the natural dynamics of capitalism will work ultimately to erode any gains the workers are able to win. Such erosion can be blocked, ultimately, only by moving beyond capitalism to the economic democracy of socialism. In the struggles of today, it is necessary to educate about the requirements of the future. In multiple ways, the struggle for reforms in the here and now must be linked to the struggle for revolutionary change.

In order to advance its interests, then, the working class must organize itself not only as an economic movement but also as a political movement, and it must be politically independent from the capitalists and other upper-class elements organized in various liberal, conservative, and hybrid political parties. The workers must utilize their trade unions, reform organizations, and political party to struggle for political power. When they are able to win political power (which will have to be organized in more radically democratic structures than those developed by the capitalist politicians), this will constitute a working-class revolution, and they should use this revolutionary power to begin the transition from a capitalist to a socialist economy. In this entire process, the workers must ally themselves with all laboring people (especially farmers, peasants, etc.), and with all of the oppressed, whose liberation must be part of the working-class political program.

Because capitalism is a global system, the struggle of the working class for a better life and for socialism must be global, and the development of socialism can only be accomplished on a global scale. Lenin played a major role in grounding revolutionary strategy in a clear understanding of imperialism, but the global and exploitative expansiveness inherent in capitalism is laid out clearly in the Communist Manifesto. Marx and Lenin shared a most thoroughgoing revolutionary internationalism, rejecting the notion that a single country could somehow, on its own, achieve the socialist future. Workers of all countries will have to unite in a multi-faceted international movement to bring such a future into being.

There is also the matter of organization — to which Lenin is correctly credited with giving intense attention, but in which (it seems to me) he followed Marx to a large extent. August Nimtz, in his recent book Marx and Engels: Their Contribution to the Democratic Breakthrough, did a nice job of demonstrating the seriousness with which Marx and Engels approached the organization question. As they emphasized in the Communist Manifesto, Communists are the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class movement seeking to push forward all the others – because they are the most theoretically clear element within the working class, with a definite understanding of “the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement.” There is a need for democratic, cohesive, effective organizations of working-class activists to play this role. There are radical insights and militant upsurges that animate the working-class in its struggles — but much serious work needs to be done to help draw together and deepen such insights into consistent class consciousness, and to sustain and broaden such upsurges into consistent class struggle that can lead to socialism.

Questions must be raised about how all of this can be translated into something relevant to the realities of our own time. Marx, Lenin, and the Revolutionary Experience wrestles with such questions. Marx and Lenin are essential for dealing with our own realities — but it is not a simple matter to make use of those ideas in a manner that actually advances the struggle for a better world. We have a lot of work to do to accomplish that. I hope my book helps.

MY: My wife and I have been traveling around the United States for five years now, and I must say that what we have seen and heard doesn’t give us much hope for radical change any time soon. How do you see the contemporary United States? Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

PLB: I know what you’re saying. The organized Left is a shambles, and the working class is able to see nothing that stands as a serious alternative to the capitalist status quo. It is by no means about to spontaneously transform itself into a class-struggle force for socialism. But I have to confess that I am an optimist.

The great Italian Communist leader Antonio Gramsci has been credited with saying that we must be pessimists of the intellect but optimists of the will (although actually he took that from the French novelist Romain Rolland). I am not sure exactly how that is supposed to be understood in our time — it seems to have been fashionable, in recent decades, for radical activists to say: “I will myself to be optimistic even though my brain tells me we can’t really win.” I just don’t see things that way.

I’m getting old — I’m almost sixty! That means that I have been part of the working class, and have known working-class people, for a fairly long time. I like working-class people — they make me think of Carl Sandburg‘s wonderful book-length poem The People, Yes. Some are Democrats, some are Republicans, some are none of the above. All of us are screwed up in some ways – and some of us are screwed up a whole lot more, while others seem to be in pretty good shape as human beings. Some look to Jesus in a way that doesn’t make sense to me, others look to Jesus in a way that does, and many don’t seem to look to Jesus at all. Some seem to believe in the President (whoever that might be at any given moment) and some don’t. Some want to buy lots of stuff, and some do but can’t really afford it, and some seem to not be into that at all. Some like the same movies and music that I do and some don’t. Most don’t really know who Karl Marx was or what he had to say, which is a shame.

But there are some things that are true about all of the working class. It is composed of people who either sell their ability to work for a paycheck (or are trying to, or really need to) or are dependent on a family member who gets such a paycheck. It is composed of people who do the work that keeps our whole complex society alive and functioning. These are people who are exploited, who create the wealth that is — for the most part — taken away from them, but who are as indispensable as their exploiters, ultimately, are not. Many are aware of two Golden Rules: one says “he who has the gold makes the rules” (most laugh at the joke and hate the reality), the other says “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” (most think that sounds pretty good).

Although some of us are treated like trash, all of us are worth something. There is a lot of humor and creativity, strength and resiliency, beauty and sensuality, cleverness and wisdom (with generous helpings of foolishness and stupidity, to be sure!), and what George Orwell once praised as “plain human decency” (despite some of the opposite) in the working class. And within this class is a strong bias (despite contradictions) favoring the notion of “rule by the people.” So much of this — it seems to me — is just a step away from socialism.

Then there is capitalism. My father was a class-conscious socialist and working-class organizer, and he used to say: “The boss is the best union organizer.” I think that’s true, and capitalism is the best socialist organizer. But “one” organizer cannot do the job alone. You can’t organize an effective union without a number of workers getting into the act. You can’t organize for socialism without workers getting into the act on an even larger and more intensive scale. We need organizations of union activists to organize effectively to defend the immediate interests of the workers. We need organizations of socialist activists to educate and organize effectively to advance the ultimate interests of the workers.

In 1867, who would have thought that the immense power of Russia’s tsarist autocracy would be overthrown fifty years later? In the 1899, who would have thought that a mighty revolution would establish the People’s Republic of China fifty years later? In fifty years you and I will be “gone with the snows of yesteryear.” But some of the people reading this interview will be alive, and some of them — and in some cases their children — will have been able to continue our work (more effectively, I would hope) in a manner that could bring about the transformation to which we have been committed. I think they will be aided mightily, also, by the fact that they are not alone in the world — that there are many in other lands who are engaged in the same struggle. The struggle for a decent life and a better world will go on not only in the United States but also in Latin America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and elsewhere, with gains in one area helping to inspire, teach lessons to, and strengthen the struggle in the other areas.

The one thing that introduces a pessimistic note for me is the question of whether humanity actually has enough time, given the destructiveness of capitalism to our planet, to create a better world. If the working class is not able to bring about the transition to socialism soon enough, perhaps we will see the common ruin of the contending classes that the Communist Manifesto warns us about. This adds an element of urgency in my view of our situation.

MY: Any last words for us about your new book?

PLB: It seems to me that this book will have value to the extent that people engage with it, and that the best form of engagement will be to try to utilize whatever insights it may offer in our lives and in our struggles for a better world. An essential part of this, I think, will involve its getting mixed into discussions of “what is to be done” to make the world a better place.

I think there are people who are not activists who will find this book interesting and useful. I am certainly interested in connecting with them. I am also very, very interested in connecting with people who are activists. It is a book largely inspired by them and by their counterparts in previous generations.

The book itself is a set of cross-generational and global dialogues among people from a variety of political tendencies. My hope is that it will become a part of a series of discussions and debates and explorations on how to build and make more effective a global movement — or set of interrelated movements — for social change in which the free development of each will become the condition for the free development of all.

MY: Thanks for this interview, Paul. I know our readers will enjoy it. And I hope each of them goes out and buys your book!

Paul and Nancy

Michael D. Yates is associate editor of Monthly Review. He was for many years professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. He is author of Longer Hours, Fewer Jobs: Employment and Unemployment in the United States (1994), Why Unions Matter (1998), and Naming the System: Inequality and Work in the Global System (2004), all published by Monthly Review Press.

|

| Print