A Sense of History?

“Kahin building, kahin trame, kahin motor, kahin mil; sab milta hai yahan par bas milta nahin dil,”1 croons the late Johnny Walker to Sahir Ludhayanvi‘s immortal lyrics (CID, 1956) while ruing the difficulties one has to face in finding true love in a world of industry, automation, and speed. In this, one already finds a critique, also seen in the movies and songs of Bimal Roy and Guru Dutt within a decade of the Indian Independence, of the Nehruvian “Socialistic” vision. These movies portray the exploitation and poverty at one end (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) and the brutalizing and alienating selfishness engendered by “modern” life that doesn’t even spare relations of love (Pyasa, 1957). Little did they know that there are other ways of becoming happy and winning eternal love!

The Story

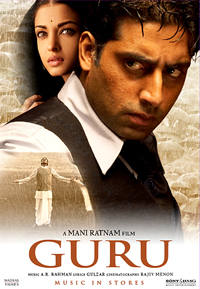

Mani Ratnam’s paean to Capitalism, entitled Guru, shows the way. Shot in picturesque locales of verdant forests and enchanting rivers, with beautiful people, romantic lyrics, and scintillating music, the movie narrates the rags-to-riches story of one Gurukant Desai, son of a teacher (and failed businessman). It traces his journey from the village of his birth, his growth into a worldly-wise man in Turkey, and his return to India, to the big bad world of textile business in Mumbai, where he triumphs. Along the way, he receives true and enduring love from his beautiful wife Sujata; meets his mentor and bete noir Nanaji, owner of the Swatantrya newspaper; and eventually emerges as the patriarch owner of the most successful business house (Shakti Parivar) of the country. Not given to hearing a “No” (“na nahin sun sakta”), he achieves his success by breaking all the rules of the game. He raises his initial capital through a marriage for the dowry it brings, besmirches the reputation of a business opponent, uses bribes (“salaam”) and brawn (“laatein”) to get his way, indulges in financial irregularities, corruption, and fraud. All this without losing his boyish charm. As the movie draws to an end, Guru has it all: love of his devoted wife and family, respect of his persecutors as well as shareholders, and untold riches. What more can one ask for? Funny guy, the other Guru (Dutt)!

Mani Ratnam’s paean to Capitalism, entitled Guru, shows the way. Shot in picturesque locales of verdant forests and enchanting rivers, with beautiful people, romantic lyrics, and scintillating music, the movie narrates the rags-to-riches story of one Gurukant Desai, son of a teacher (and failed businessman). It traces his journey from the village of his birth, his growth into a worldly-wise man in Turkey, and his return to India, to the big bad world of textile business in Mumbai, where he triumphs. Along the way, he receives true and enduring love from his beautiful wife Sujata; meets his mentor and bete noir Nanaji, owner of the Swatantrya newspaper; and eventually emerges as the patriarch owner of the most successful business house (Shakti Parivar) of the country. Not given to hearing a “No” (“na nahin sun sakta”), he achieves his success by breaking all the rules of the game. He raises his initial capital through a marriage for the dowry it brings, besmirches the reputation of a business opponent, uses bribes (“salaam”) and brawn (“laatein”) to get his way, indulges in financial irregularities, corruption, and fraud. All this without losing his boyish charm. As the movie draws to an end, Guru has it all: love of his devoted wife and family, respect of his persecutors as well as shareholders, and untold riches. What more can one ask for? Funny guy, the other Guru (Dutt)!

The problem is how this story justifies our highly individualistic society. In one of the initial scenes where Aishwarya’s usurer father contemptuously refers to the “cowardice” of the sloganeering, red-flag-bearing ex-lover of his daughter. The battle lines are drawn. Cowardly Labor is juxtaposed with Valiant Capital, and the “battlefield is the human heart.” This valor (“himmat”) is again invoked by Guru at his trial by the justice department as he justifies frauds as the only recourse left for people, who like him, want to become wealthy.

The film demonstrates no understanding of the science of wealth creation. Wealth is not conjured out of thin air or created only by “valiant” illegality or bullying, as the film implies. It involves production of commodities that are then sold at profit. Since profits can be made only by controlling costs of production, and since investments in machinery cannot be avoided, the only way this can be achieved is by exploiting labor (by under-paying workers and extracting surplus work from them), using the cheapest (often environmentally damaging) technologies, and riding on free or under-priced natural goods such as clean water and soil as raw material. But why talk about this? After all, did he not manage to make a few lakh ordinary people (“aam public”) rich? Didn’t even a taxi driver marry off three of his daughters, all thanks to the money he made on the shares he has invested in Guru’s Shakti Enterprises? True, capitalists like Guru do indeed enrich a few who otherwise may have languished in semi-poverty. But this “trickle down of wealth” is possible only at the cost of denying others even the basics of survival, inflicting ecological depredations, and remorselessly deepening the division in society between the haves and the have nots. This chasm is what maintains the “trickling up of wealth” for the accumulators of capital.

Guru’s vision, shown at the end of the film, is of a nation/society of share-holders and consumers, not of citizens. He brazenly compares himself with the father of the nation, forgetting that Bapu’s (Father of the Nation Mahatma Gandhi’s) vision of India was based on building a self-reliant local economy and not on predatory and imperialistic ambitions (to make his firm “duniya ki sabse badi company,” the world’s largest company). The Gandhian ethic that the world has enough to meet everybody’s need and not enough to meet even a single person’s greed is violated by Guru’s endorsement of creation and multiplication of wealth, commodities, and wants through the capitalistic route. This system also creates the culture of exploitation, unemployment, and wars, of relentless consumerism and depressed and unhealthy human beings. Since such issues do not concern the director of this film, the movie has a surreal quality about it that makes the daily grind of real people largely invisible. If entertainment is only about mindless consumption, Guru is a superb “finished product.”

1 “In this city of buildings and trams, motor cars and mills, everything is available except a heart.”

Milind Wani, Manju Menon, and Kanchi Kohli are member of the Kalpavriksh Environment Action Group.

|

| Print