This article is a modified and developed version of a chapter from Social Class in Contemporary Japan: Structures, Socialization and Strategies, edited by Ishida Hiroshi and David H. Slater, Routledge, 2009. For a brief outline of the book’s arguments, please see <japanfocus.org/data/Social_Class_5.htm>.

Introduction: The “New Working Class” of Urban Japan

Tomo was a first-year and Keiko a third-year student at Musashino Metropolitan High School,1 a working-class high school in western Tokyo. I have known them since the early 1990s, when I began working at their school. Two snapshots from those first years illustrate some features of family background, survival strategies, and career trajectories. These are features that they share with many working-class youth all over Japan, especially in the urban areas where public schools are more finely ranked and the labor market is larger but also more unstable and precarious. Part I sketches how class and culture are interrelated within the context of Japanese secondary education. Part II focuses on the ways different class groups navigate the transition from middle to high school. Part III focuses on the sorts of orientations, goals, and strategies that characterize school culture at Musashino High, a place where working-class culture takes institutionalized form through practice. The final part traces these young people’s trajectories into the bottom rungs of the service labor market and into their new status as “freeter.”

Tomo’s mother is pleading with her son’s teacher, trying to do what she can to keep her son in high school despite his having been caught smoking, again. Tomo was very involved in his middle school homeroom and club activities, at least until the end. Now, having failed to get into any school other than Musashino, he is in school but demoralized. He has been caught smoking twice before and suspended once for half a day. His tone varies from simmering resentment to feigned unconcern. He points out that there are almost three smoking cases a day at this school, so his getting caught only twice in the first year is not so bad, “on the mathematical average.” While bright, at Musashino High Tomo has stopped following most of the lessons and is beginning to think that maybe he is not “cut out for” school. His mother asks his teacher about his participation in the baseball team, a widely accepted index of school integration, especially for a student struggling academically. The teacher turns to Tomo, who replies deadpan: “Didn’t you know? Everyone has quit because all the teacher wants to do is drill.” (This is true — the baseball team does not have enough players to field a team.) His mother has reassured him that if he would just come to school, he could graduate and then maybe play baseball when he gets a job. Tomo’s reply to his mother is a sarcastic indictment: “You mean, so I can get a job like Dad?” The teacher asks Tomo’s mother about her husband’s job at the discount electrical shop in the area. She mumbles something, but, in fact, she does not know what sort of work Tomo’s father is doing these days because, after he was laid off from what was a temporary job anyway, he has not lived with them for many months.

Like many working-class youths who end up at Musashino, Tomo is somewhat bewildered at how he got to this place or where to go from here. The same is true for his mother. There is no suspicion of anti-education culture in their household or neighborhood, and his mother fully expects Tomo to graduate and get a job. She believes in school as a way to secure a job and a future. She makes another appeal: “But Sensei, as his homeroom teacher, how do you think it is best for Tomo to return to the regular flow of the class,” a question that rests on the assumption that success in high school relies on, or at least begins with, one’s contribution to the school as a moral community. The teacher labors under no such illusions, as he takes out the school rulebook to show Tomo and his mother the chart that clearly shows the punishment for missing classes or breaking rules — three suspensions and then withdrawal.2 Flustered, his mother protests that this is premature. “Tomo is kicked out already?” The teacher shakes his head and calmly replies, “I just wanted you to know how students move through the school.” All three of them stare blankly at the chart in the rule book.

Keiko was a senior when I first interviewed her formally, and like most students who make it to their final year at Musashino, if they have learned anything, it is the art of survival by withdrawal from the school as a social and emotional center (a lesson the struggling Tomo had never learned by the time he dropped out). She is averaging just above 30% on her term tests from two classes, but as she points out, there is really nothing to worry about:

School is fine. I stay out of the headlights of the teachers and I guess I am not rude, and also, I have good looks. Let’s face it, I could be a fashion model if I were not in school. I might be a model, afterwards. Anyway, they don’t want to fail me. They don’t really want to think about me at all. Sometimes, a teacher will wake me up in class, and ask why I am so tired, and I say “homework.” This is funny to them, big laugh because everyone knows that no one is doing much homework here, but what can they say? I can pass these tests, if I take them enough times.

Tokyo snack bar |

Keiko was never part of the school routine, even in middle school, when she spent her time smoking and drinking with an older boyfriend. Now, in high school, she works two part-time jobs — one on the weekend at a neighborhood fast-food restaurant where her mother used to work before she got sick. The other is at a place called “Twilight Snack,” a sort of hostess bar where high school girls wear nice school uniforms (not from their own schools), serve drinks and chat with the male customers (“and nothing else,” as she points out) for good money between the end of school and 8 or 9 pm. She says that she first thought of this because her father worked as a freelance accountant in a similar place once. She does not tell her mother about this job, because she knows that she is treading close to the line of respectability. She has told me since on a number of occasions that she never stays overnight, never misses the last train (about midnight), and never sleeps at her workplace or in a club. She tells me that she knows some other girls who end up in Ikebukuro (a Tokyo entertainment district) all night, and “you never know what happens to them. They usually drop out of school pretty soon after. That is not me. I always go home. I will be in school until I graduate. I promised my mom.”

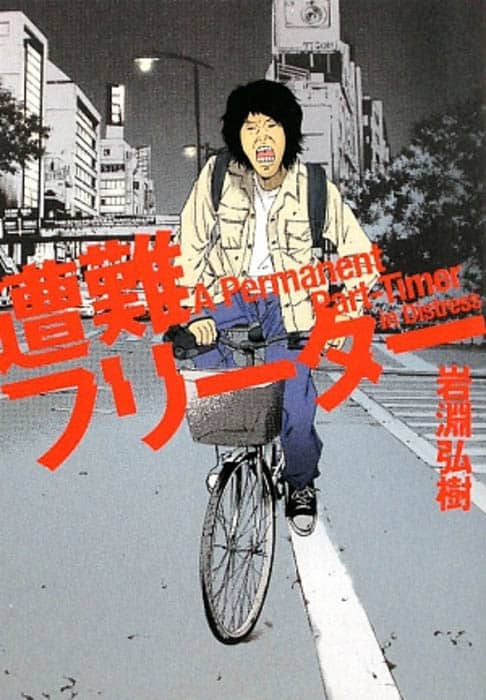

A bike like the one Tomo first used. He eventually began using a small motorcycle when he increased his hours after graduation. |

When Musashino students (both graduates and the many who withdraw) get jobs, usually they are of short duration, with little security and few if any benefits. They go on to do the work that every society needs to have done — cleaning, serving, delivering, cooking, entertaining. Tomo never graduated. He enrolled in a trade school to get a certificate in computer repair, but did not finish that either. He kicked around at various delivery jobs until he began planning and managing the routes for the bicycle delivery carriers of a Tokyo newspaper. He is a part-time worker, with no prospects of any more stable employment in the future. When asked about Musashino, he recalls it with bitterness, as the result of his abrupt and unjust relegation to the bottom of his middle school class, once things got difficult heading into high school. After graduation, Keiko did not become a fashion model but instead worked in a number of clubs and bars, where by her own reckoning, she often crossed the line of respectability she had kept during high school, but for much better pay. Today, she waitresses and manages the accounts (“just like my dad,” she says) in a dank hostess bar in a rather upscale neighborhood. She, too, works what amounts to full-time hours (as many as 60 per week) but is paid by the hour with no prospect of promotion. She looks back on Musashino with much more affection, as a time of play with friends and being indulged by her teachers, but also points out that she would probably be doing what she is doing now whether or not she had gone to high school.

Tomo and Keiko are ochikobore, a term which might be translated as “fallen student” or “dropout,” but is in fact used to identify a student, still in school, who has dropped down to any school as low as Musashino. All regular schools in Tokyo are divided into districts and Musashino is distinguished from other schools in the district by being at the very bottom in terms of its student body.3 It is in the same position as all of the other schools at the bottom of their district rankings all over Tokyo and other urban centers of Japan. It is also an important link in the channeling of young people from mostly working-class backgrounds into working-class jobs, and in teaching the skills, aspirations, and strategies that allow working-class youth to get by in the city. Musashino is a bit less selective than those schools at the bottom of the districts around the new towns to the south and west, but higher than those at the bottom of the “old towns” in eastern Tokyo, the traditional working-class area of Shitamachi manual laborers, shopkeepers, and small business owners (see Bestor 1990). Vogel (1971) and Murakami (1977), among others, use the term “new middle class” for the white-collar salaried men and their families that were supposed to become the norm in urban Japan. Neither Tomo’s nor Keiko’s parents graduated from college (although Keiko’s father did have a certificate in accounting, she says), nor did they have regular jobs in an office. Yet, neither were they doing regular manual labor, as the term “working class” might have suggested to earlier generations. Very few Musashino parents work in the sorts of jobs that offer full-time, lifetime employment with benefits and stability, the sorts of jobs that were once thought to characterize both white- and blue-collar jobs in Japan (see Rohlen 1974, Cole 1971). Since many of these manufacturing jobs were outsourced to cheaper markets abroad over the bubble period and even in the early 1990s, white-collar jobs are increasingly hard to come by. Instead, Musashino High School caters to the children of what we might call the “new working class”: those working in service-oriented jobs, with little stability and few benefits, jobs that characterize the bottom of the Japanese labor market as in many other post-industrial economies.

Depending upon the year and class, as few as between 6% and 15% of Musashino students had at least one parent with some college experience. Across the whole school, there were as many as 25% with divorced or separated parents, far above the national average, and based on my interviews concerning their relatively fluid home life, more than half had one parent not regularly at home for some part of their school life.4 About 85% of the students’ mothers worked outside of the home in some capacity. Fewer than 5% of Musashino students had a room of their own for study. No Musashino students went regularly to any high-powered cram school during high school, and not more than 15% had remedial home tutoring. One or two students per year would get into a four-year college, but these were not competitive colleges. Those students with parents able to pay the tuition for senmon gakkō (training schools) might put off entry into the labor market. This option increased in popularity from almost none in 1990 to almost half of the class in 2005. Upon graduation in 1990, 25% got a regular (seishain) job, one that provided health and retirement benefits, annual pay raises, bonus, and the kind of job security and even life-time employment. Between 1995 and 2000, the figure was closer to 15%. And in 2005, there were only two students (out of a graduating class of 150). The ratio of part-time jobs had also shifted: in 1990 almost half the class got part-time jobs, usually at local stores and small firms.5 The most common way for these students to enter the job market was to begin sounding out the supervisor at their part-time job to see if increased hours might be offered once they graduated — if they graduate.6 (Between a quarter and a third of the students who enter Musashino High never finish.)

For much of the post-war period, students like Tomo and Keiko were under-represented in the academic literature in both English and Japanese as theorists rushed to capture the rise of the bright and shining middle-class society of post-war Japan, something that such students were not really part of. But this “reserve army” was important in reindustrialization after the war and the shifts into a more post-industrial economy. More recently, as the academic and popular focus has shifted to the “flexibilization” of the labor market in this post-bubble, neoliberal moment, these students have once again been lost in our focus on the fracturing of middle-class identity and labor patterns. But this working class, old and new, is as important in today’s post-industrial economy as it was in the high-growth economy of post-war recovery and bubble affluence. Today, these young people are filling the ranks of the fastest growing segment of the labor market: temporary and part-time workers in the lower levels of the service economy. Not only do they allow the Japanese economy to respond to new contractions and survive recessionary times by having a skilled and literate temporary workforce, but this has also allowed middle-aged workers, mostly men, to protect their own jobs, thereby localizing the effect of “restructuring” on the young. The school today is still sorting young people into low-level jobs, but as the skills and attitudes required of these jobs have shifted, so have the ways that the school socializes its students for this sort of new “freeter” work.

Culture and Class: Unity, Differentiation, and Contradiction

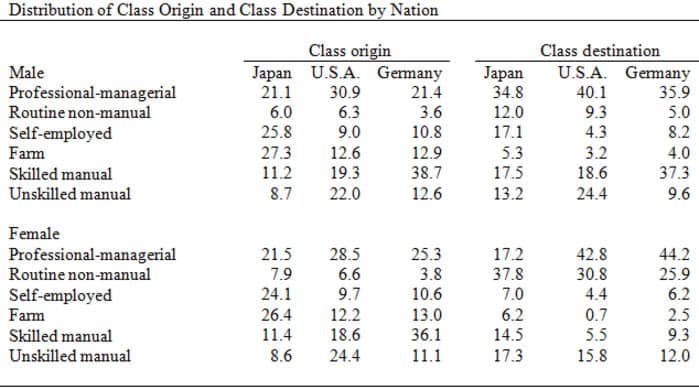

Class formation, and its reproduction, is not only an economic fact, but a social and cultural fact as well. To the extent that cultural forms guide the participation and secure the consent of individuals, the perceived legitimacy and the hegemonic force of class formation depends upon the cultural forms deployed in the representation of these mechanisms and their results. Class analysis thus must include not only the charting of stratification (or the articulation of class structure), but also must identify the differential distribution of these cultural forms and the ways in which they are deployed, manipulated, and transformed by institutions and individuals at different places in social space in ways that explain and obscure, legitimate and naturalize, these structural differences. These cultural forms are not internal to the logic of capital itself, but are selected and combined from a pool of cultural forms that are specific to a particular time and place, a particular society at a particular historical moment. So, at one pole we have the relatively universal economic workings of capitalism while, at the other, we have a very specific subset of Japanese cultural forms through which capitalism takes shape and efficacy. Class formation is thus situated between these two poles: between the economy and the culture, between the universal and the particular. The ways in which different positions in social spaces find differential cultural forms thus also vary in different societies and at different times. (See table below from Ishida 2009.)

For much of the post-war period, the social scientific literature on Japan has stressed the importance, even distinctiveness, of a shared “middle-class culture” that has somehow bound Japanese society into a single coherent order in ways that have resisted the formation of distinctive or oppositional class cultures. And yet, Ishida (1993) has demonstrated that the reproduction of social inequality is just as regular and just as effective in Japan as it is in other capitalist democracies; the chances of social mobility and class closure in Japan are roughly consistent with the UK, US, and Germany. What are we to do with these divergent and possibly contradictory patterns, ones that points toward cultural cohesion and social unity, and the other toward structural differentiation and class divergence? More specifically, how can there be class formation without class culture? How can young people be reliably sorted into a highly differentiated labor market and still show so few of the signs of class identity or class consciousness thought to characterize capitalism? If we cannot speak of distinct class cultures, what are the mechanisms of class sorting? What are the structures and contradictions of differential class socialization? What constitutes the experience of class formation?

In Japan, as in many other so-called “middle-class” societies, the deployment of cultural forms does not necessarily result in the coalescence of any “tangible” (Hall, et al.) sets of symbols that mark out some bounded population into a discrete “class culture.” Like the notion of culture itself, which has undergone such thorough critique (see, for example, Gupta and Ferguson 1997), we need to rethink class culture. We need to recognize that “class cultures” rarely resemble anything like bounded subcultural groups as imagined on the model of ethnic enclaves with distinct “class codes” (Bernstein 1977). As Voloshinov (1973) reminds us, classes do not form single distinct sign communities. Rather, different classes draw from much the same symbolic resources as the dominant culture in their attempt to make sense of their material situation in ways that often lead to contradiction. And depending upon their place within social space, different groups will draw upon different signs in different ways, experience even shared processes as differentially meaningful, as generating different options and leading to different patterns of participation. In this way, the deployment of cultural forms outlines the boundaries of struggle as much as the flow of seamless reproduction. This approach requires a level of analysis that moves away from the abstraction of “Japanese Culture” as something shared by the whole society but still does not settle into the notion of bounded “class cultures.” Instead, I attempt to identify those specific institutional mechanisms that are most responsible for the differential distribution of the cultural forms that generate, organize, and legitimate class practices that allow and obscure individual understanding and movement through this process.

In Japan, the educational system has probably been the primary institution most responsible for both of these functions. That is, schooling is the primary site for the development of shared patterns of representation and whole-culture forms so central to the integrity of adult culture and social cohesion, and at the same time, it is the primary mechanism for the social and cultural differentiation of different segments of the population into distinct class trajectories, which is central to the reallocation of young people into a highly diversified labor market. We should not imagine these two processes to be at odds with one another; in fact, it is only because school is so effective in the socialization of whole-cultural values that it is an effective mechanism for what is largely understood as legitimate differentiation. Reproduction of inequality and whole-culture socialization are always already occurring together.7 In a country where 98% of the students attend some high school, where high schools supposedly share the same curriculum, and where virtually the entire adolescent population is reallocated (from comprehensive middle schools to finely-ranked high schools) into ranked streams, education is one of the privileged domains in which to examine class formation.

The rich ethnographic literature on Japanese education provides us with a detailed image of the primary cultural forms as they are manifest in society through school. In class analysis, this work must be extended and recontextualized; the goal of class analysis is not to construct a cross-national comparison of cultural forms in order to capture “The Japanese School” (Duke 1973) or even “The Japanese High School” (Rohlen 1983) as different from another nation’s school, as is often the case.8 As necessary as these sorts of studies may be as a preliminary stage, they work by essentializing some common cultural core at the expense of noting the internal differences among schools. The goal of an ethnography of class formation is to demonstrate how hegemonic cultural forms are differently distributed and deployed to different ends at schools of different levels, and then, to show if and how these forms are linked backward to family class profile and forward to job and future life course trajectories. The ethnography of social class is still essentially comparative, although the level of analysis is not at the distribution of these forms among different societies, but within each society. That is, we need to understand how core cultural forms are differentially distributed in ways that allow different class groups to recognize, participate in, represent, and legitimate the shared functional requirements of sorting and socializing young people into different places within a complex class structure. Just as often, this distribution of cultural forms generates patterns of contradiction rather than seamless reproduction, and the deployment of these same forms often leads to a denaturalization of the process that results in young people (and their parents) questioning their own flow through the system. “Group living” (shūdan seikatsu) is one such key cultural form.

Group Living: Models of Self-Making and Institutional Management

Much of the primary and early middle-school curriculum is based on a model of socialization that has been called “group living” (shūdan seikatsu). Unlike some incipient undercurrent buried in the “hidden curriculum,” group living is the articulation of a moral community that is at the core of the formal curriculum as manifest in textbooks and teachers’ manuals, and as evident in everyday school life. It begins with students’ acknowledgment of the legitimacy, even primacy, of collective school goals. Realization of these collective goals often requires hard work, dedication, and sacrifice, but also offers a place of secure membership, warm acceptance, and “wet” indulgence. The idiom of wetness implies high levels of the emotional and largely unstructured involvement characteristic of an enduring relationship of belonging and even identity and is most often contrasted with what might be called an instrumental or “dry” relationship that one enters into for personal advantage. Full participation in group living requires restraint (enryo) of one’s own personal desires, both as a way to support others with feelings of empathy and mutual dependence, but also as a precondition that allows others to support you. In this way, an individual demonstrates fitness to be a member of a collective. In its more developed form, participation comes to imply taking personal responsibility for these collective goals for others and for the cultural project of developing a self that is connected to and supportive of others. Thus, rather than setting individual goals against collective goals, group living becomes the foundation for individual development of self, a channel through which self can develop and mature. In short, you make yourself valuable insofar as you contribute to others within an institutional context.

But this alignment also enables group living to function as the foundation of institutional management or, more generally, governance (Rose 1989). It is as much about the management of individuals into coherent shapes and projects as it is a structure that allows those individuals to develop at all. It is as much a site of social order as it is one of social control. Group living demonstrates this capacity for governance in its representation of legitimate power as “soft authority,” a diffuse set of priorities represented as naturally emanating from the collective needs of the group, rather than from the station or office of a superior such as a boss or a teacher.9 In this way, group living aligns the individual and the collective in mutually constitutive processes of self-making and institutional governance.

Group living in Japan is not something that young people grow out of and leave behind in primary school. In fact, it is the educational manifestation of roughly isomorphic patterns of collective order and control found in a wide range of adult social institutions. Some variant of group living is present in most sites of middle-class participation: clubs, university and professional academic associations, sports teams, company training practices, and most importantly, in virtually all corporate white-collar and blue-collar contexts. Stability, mobilization, and productivity of adult institutions, especially work groups, are often structured through these principles. On the other hand, failure to secure such a place in one of these corporate groups risks relegation to spaces of largely anomic social relationships, ordered by “dry” criteria of contact, a world with ordered assumptions of distinct identities and divergent interests. The learning of group living in school is thus an important lesson for participation in and belonging to adult society. Where social identity is bound up with the full participation of institutional membership, learning the routines and ethos of the moral community of group living is a primary function of school socialization in whole-culture values. This group living model of whole-culture socialization orders the daily routines of primary school and the beginning of middle school, but is marginalized as middle school students begin to be sorted and streamed into highly stratified high schools.

Academic Maximization and Class Sorting

Middle schools, like primary schools, accept students in their immediate residential area, and thus reflect the diversity of their neighborhoods. Once, urban neighborhoods were said to be more diverse in Japan than in many countries,10 so that each school demonstrated an internal heterogeneity more or less similar to that of other middle schools. But today, things have shifted. First, although not as uniformly or dramatically as in many other countries, urban neighborhoods do differ in terms of class composition, especially since the wild fluctuations of land prices during the bubble period forced out many older and less wealthy residents. Middle schools in wealthier areas have more parental participation and support (including financial), which results in better facilities, a wider range of programs, and more parental influence at the school. Based on these differences, some middle schools are sought after by parents because they have a better reputation for getting students into better high schools. In this time of declining student populations and greater support of market-oriented solutions to what were once governmental services, many districts in Tokyo allow students from other districts to enroll in their schools, thereby facilitating something that looks increasingly like ‘school choice’ patterns familiar to other countries. Nevertheless, middle schools are not (yet) as universally or finely ranked as high schools and have much broader class heterogeneity than do high schools. Thus, this shift from middle to high school still represents the most significant moment of reallocation of the adolescent population.

The second trend is more dramatic and obvious in its effect of class-based sorting. More parents are enrolling their children in private schools, even from elementary school, thereby removing them from the public school mix altogether. Earlier in the post-war period, the top high schools in urban areas were almost all public — the highest achievers saw public school as insuring a quality education and an effective means of social advancement. Private schools were thought of as a place for those who could not get into a desired public school, a way to buy your children a better place than they could secure on the basis of achievement. But today, the trend has reversed: the top schools in any given district are mostly private, and schools like Musashino are not only for those who cannot or won’t study, but also for parents who cannot afford private high schools. (There are no high schools below the level of Musashino, public or private.) In Tokyo, only about 5% of students go to private elementary school; in middle school is it about 25% who go to private school; and by high school, more students are now going to private than to public schools. It is difficult to confirm the class background of those parents who move their children when and why, but the common wisdom among teachers, based on their interviews with parents, is that parents who can afford it usually choose between two private educational options in order to compete on the educational market: private schools (which often, but not always, are assumed to reduce the need to attend a cram school because they are more effective at placing their students in good secondary schools or colleges) or cram school (while their children stay in public school). If some portion of middle schoolers has already moved to private schools, then the sorting process into high school will proceed within somewhat different parameters, but the mechanism is still the same. The results are somewhat chilling. If those who can afford it move their child into private school, the public schools end up with those students who are, in the words of one public school teacher, “poor enough so that they have to rely on public schools — it is a shame.” Another teacher called it “educational apartheid.” While this is a stronger statement than many teachers might support, the point is clear: Tokyo, and other large cities, end up having a social class divide that is played out between public and private schools.

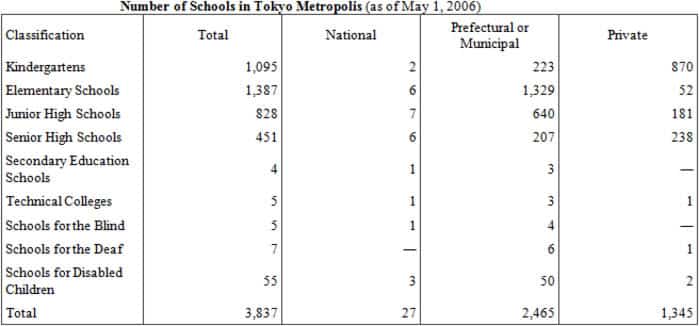

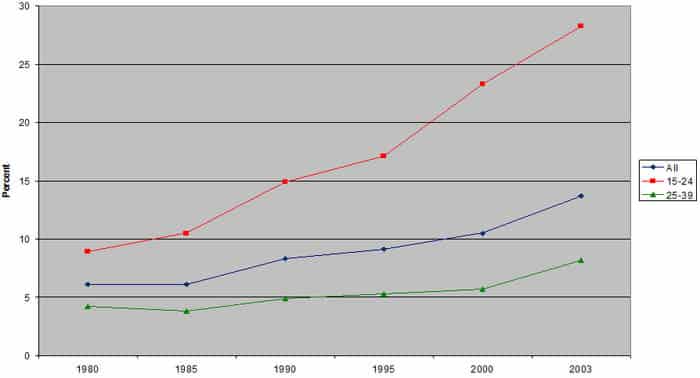

Note: Excludes senior high school correspondence courses, senior high school postgraduate courses, and technical college postgraduate courses.

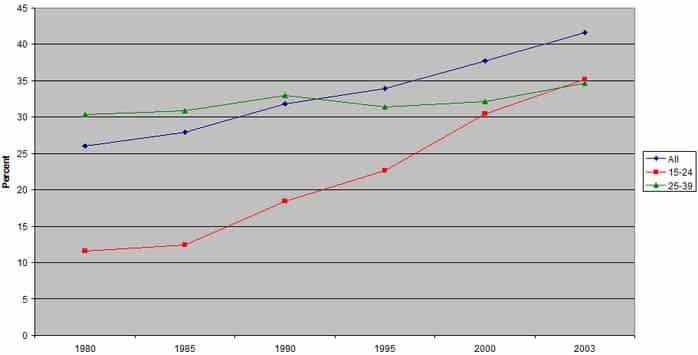

Note: Excludes junior/senior high school correspondence courses and senior high school/technical college postgraduate courses.

Children whose parents select the second path — staying in public school and investing in cram school — as illustrated below — progressively move away from the public school as the curricular, moral, and social pivot of their lives as a result of their focus on cram school. The sorting process is mediated through the middle school as follows. During elementary and early middle school, the curriculum is substantially uniform across schools and focuses on the various forms of social relations that are needed to form productive and coherent school cultures, that is, group living. But at the end of middle school, all students are reallocated to high schools on the basis of their achievement test scores. The top students in each district are streamed into the most selective high schools, and low-achieving middle schoolers end up at the bottom-ranked high schools. In order to facilitate this reallocation, the middle school curriculum becomes increasingly academic, ensuring that students are sorted into a reliable array of academic streams that find formal articulation through high school entrance exam scores (hensachi). This is the most obvious juncture of class sorting in a young person’s life course, a transition from relative class heterogeneity in middle school to class homogeneity in each of the strictly stratified high schools. This redistribution of students is broadly predictive of future educational, occupational, and life course trajectories, as well as being closely coordinated with family background. It is the first instance of, and perhaps the clearest indication of, the class structure of the whole society, held up for all to see at precisely the moment when it first emerges as an institutionalized fact.

Whole-culture socialization, as embodied in group living and practices of class sorting manifest through school reallocation, works in contrasting ways to produce different school cultures, different sorts of institutional order and control, and different sorts of identities. Rather than the whole culture curriculum of group living that stresses contribution to a collective moral community, entering into a desirable high school depends upon a development of individualistic achievement strategies, whose outcome is measured in the minute relative differences among students. This collective moral order comes into direct conflict with the larger imperative of capital to sort and socialize students for different places within the highly stratified labor market. New goals and strategies for reaching these goals develop: rather than contributing to a warm and wet moral community, middle school becomes more of a competitive market involving a rearticulation of individual values based on a narrow criterion of academic success. Group living that once served as the foundation for constituting a coherent and meaningful self is juxtaposed with the imperative of developing coherent and effective maximization strategies. In fact, the group living strategies learned in primary school have little value; indeed, they often retard success within this new academic curriculum. Individual priorities, peer relations, and deployment of institutional authority all shift accordingly. Some students are better able to negotiate this shift than others.

The next section shows how students from different class positions are caught in this transition in different ways; they have different resources to draw upon and different class-specific goals that lead to different survival strategies. For students from richer families, this transition is an all-important moment which they start preparing to exploit years before. For students from working-class families, those who end up at high schools such as Musashino, the transition is one that is intellectually confusing and often emotionally draining, as they fall out of the community that once supported them (and which they once supported) to the bottom of an academic hierarchy. While young people from more elite families are learning maximization strategies through cram school, for example, working-class students do not even recognize the significance of this moment until it is already past.

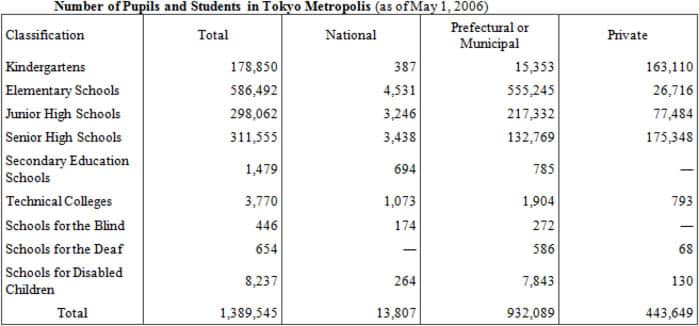

Organization of the School System in Japan

Organization of the School System in Japan

Middle School Sorting

We often imagine class formation to function somehow beyond the recognition of individuals, often because it is obscured by ideas of race (Ogbu 1992), gender (Willis 1977), or other more accessible forms of identity. But because the process of class differentiation that occurs during Japanese middle school is the result of a relatively harsh disjuncture between group living and a more maximizing ethic of academic achievement, both are denaturalized and very much available as objects of explicit reflection, at least temporarily.11 Interviews and fieldwork revealed clear awareness of the workings and significance of this sorting process, even if it was rare to find any students able to articulate the link between school sorting and the larger class implications that it carried. More obvious was how differently students from different class trajectories understood and represented this process. By juxtaposing the experience of those students who ended up at elite schools with the experience of students like Tomo and Keiko from Musashino, we can begin to sort out the ways in which class formation is experienced.

Sara, a first-year student who entered one of the well-known elite high schools in Tokyo, explained:12

I knew that getting into this school was important for me, for my future, because this puts you on the track. And if you are not on the track, well, I don’t know, but you don’t get where you are trying to go. You cannot just go to any high school and then get into a good college.

She continued: “My middle school was pretty good, I guess, and some of the teachers really helped you, but they could not make everyone ready [for high school] because we were all going to different sorts of high schools. It’s not the teachers’ fault — it’s just impossible because lots of the kids just did not care about studying.”

Sara’s parents did what more than 90% of the parents of the students in her homeroom class at her elite high school did: enrolled her in cram school in a strategic way to maximize her chances.

The cram school was close to my house. My father used to joke that we moved houses so we could be near the cram school, but I don’t know. Actually, he also said that the cram school was so expensive that we could not afford to pay train fare to some other cram school, so I had to go there. [This was offered and accepted as a joke by all the students present, humorously juxtaposing the relatively small train fare to the large tuition her father must have paid.] I went every day, with no commuting time back home. That was the key I think. Some of my friends commuted an hour or even 90 minutes each way to cram school. But for me, no time spent sleeping on the train. I could just go home, take a short nap and then work again. Or even skip my nap.

It would be tempting to say that academic success is less the result of talent and hard work than it is bought and paid for in the urban market of secondary school in Japan, and in some sense this would not be untrue. But the ability to allocate family economic resources to cram schools only provides opportunity; it does not secure success. Parents’ money cannot buy success for children without the creation of a maximizing subjectivity, one that depends upon the definition of self as a possessive self, one defined by what can be accomplished, by the scores that can be generated. The matter-of-fact calculation of commuting time and study results was a common topic among Sara and her elite classmates. Sara seemed very bright and her narrative speaks of hard, directed effort over an extended period of time — just what she or any other student would need to get into the elite school she got into — but we see that this effort must be directed through particular institutional channels, in this case, cram school.

In contrast, Tomo explained his path through middle school to Musashino with a sense of confusion, even bewilderment, rather than strategic intent:

I know that we were supposed to work hard in middle school, really, that’s all we were doing. Studying for tests and taking tests. One after another. It was so sudden. The things that I liked to do [science projects, anything outside of the school classroom] we just did not do. And if you were going to pass these tests, you couldn’t even do sports.

Tomo was active in class affairs and a real contributor to his homeroom for festivals and class projects, patterns of participation that embody the best ethic of group living. But he appears never to have caught up with the curve into more academic focus as it developed in middle school. Tomo’s mother told me in an interview that “really, in middle school, Tomo worked hard, spent all of his time in school, so I thought he would be okay.” She did not think that cram school was necessary as long as he worked hard, “because I thought his teachers would help him out more.” Another day she explained, “I’m not sure where we could have found any money to pay for cram schools. Not for middle school. Maybe for high school, if he continues to struggle.” In comments like these, we see both economic handicap, but also a set of priorities over the allocation of discretionary income within a family budget. Neither Tomo nor his mother was engaged in a strategy to maximize his chances and saw school as an opportunity to do so. Like so many of the Musashino narratives, their narratives were grounded in a rhetoric of getting by, developing compensation strategies, and covering up.

Tomo and Sara both went to public comprehensive middle schools that streamed young people into the full range of high schools, public and private. Tomo, and other students who ended up at Musashino not only did not make the cut for the desirable high schools due to their low levels of achievement but, in some fundamental way, did not realize the scope and significance of the academic shift during middle school. We can assume that smart and able young minds are probably distributed across the spectrum of class positions in roughly even patterns. To be sure, there are instances of students who enter top high schools and colleges without going to cram school, but these are the exception to the rule — for example, fewer than 10% of Sara’s classmates at her elite school. Class practices might best be seen in the larger orientation to and awareness of this pivotal moment. Coming from his family background and without the sort of cram school that Sara attended, Tomo had little systematic preparation in terms of test-taking skills or the larger discipline of competitive strategies (including those that extended all the way down to the precise calculation of the impact of train time on study). This transition found Tomo, and many others at Musashino, ill equipped and unprepared. Less than any particular low test score, it is more the lack of awareness of and systematic preparation for this shift that is the key feature of Tomo’s working-class trajectory.

Kento, a classmate of Sara’s, explained middle school this way:

I enjoyed my [middle school] classes and my homeroom teacher was great. She was always giving me extra work, until I became too busy with cram school. I learned all sorts of things, but not that much of what I learned ended up on the entrance exams for high school. We took all sorts of “mock tests” and I did very well on these, but they were just something that the teachers made up themselves. My teachers at cram school actually had the tests that the different high schools gave [from previous years] and they had figured out the techniques to help us pass. I knew that our regular [middle school] teachers could never do that. It was just a different thing.

Tomo and most of his first-year classmates at Musashino reported very negative feelings toward schoolwork, and their middle school teachers in particular, who in their minds were mostly pushing them into, even punishing them through, test taking. They had no luxury of distance and their narratives were as emotional as they were wet. Narratives of being ignored and abandoned, even betrayed, point to a representation of teachers as failing to live up to expectations. These expectations do not involve any transmission of useful knowledge or test-taking strategies, but whole-person care and guidance, traits that appear to be mostly generated from representations of group living. Working-class students often reported being locked into relationships of conflict with their teachers over their poor test performance.13

Tomo recalled his middle school this way:

[The teachers] stopped caring about the students and we never did anything except tests. The only time we ever did anything as a homeroom was once a week when we had to, and even then, we usually used that time to study vocabulary lists or something. They would keep on complaining about each test. They would read out test scores to the whole class, or post them on the wall, and everyone knew who got what. They all knew that I was at the bottom, and was dragging the class average down. I said, “Hey, everyone below the middle is also pulling it down,” but I was always blamed. They always went after the bottom dwellers. Like me. After a while, you see what is going to happen and there is nothing you can do. Nothing to do about that. You have to give up. But I hated it. I always hated it.

This is not to suggest that group living is completely extinguished in middle school. In fact, there is still a framework of group living, albeit challenged and embattled, that rearticulates the macro-level contradiction between moral community and achievement in more immediate form within the daily life of the school. As one teacher at Sara’s high school explained,

When students focus too much on cram school, it pulls them away from participation in [middle] school. Even if they are physically here, when their future is focused on results that come from cram school, they become selfish and start putting their personal things ahead of classroom things. It becomes very hard to teach a class like that anything but the textbook. I guess this is understandable — it’s the reality of [middle] school — but nevertheless, it’s a problem for us when so many students are spending time in cram school.

While Tomo felt conflicted between these divergent possibilities, students like Sara quickly learned how to balance them in ways that satisfied both by compartmentalizing. Sara explained that as she progressed in middle school, she would spend as much time on her school lessons as was required for her to pass and as much time on her club activities as was available, but first allocated the time and energy necessary for success at cram schools. She knew that the path to success did not pass through her middle school classroom, and this distance from the school as sorting mechanism allowed her to avoid some of the contradictory tensions that characterize middle school, enabling her to keep a generally positive, although rather dry, relationship at her school. As with her high school teachers, her relationship with her middle school teachers might be described as positive or negative, friendly or unfriendly, as the case may be, but rarely was there much emotion or complexity. There did not seem to be much at stake in these relationships, which is what we would expect given their tangential relationship to her larger instrumental goals.

Sara and her classmates who entered the high-level schools reported little conflict between the requirements of cram school and middle school. Successful maximization strategies almost always included the ability to move back and forth between these two spheres with ease and fluency. Sara explained, “My time was somewhat flexible [since she lived close to the cram school], but there were also times when I just had to leave. Sometimes the teacher understood that I just could not always be around after school.”14 Sara’s classmate Kenji recalled, “I enjoyed my other activities at school, but everyone knows that you don’t get into a good high school by spending all of your time cleaning up the classroom or being good at club activities. Some kids do that, but not the students who go to cram school.”

For Tomo, middle school was an arena of conflict and struggle. He did not experience the shift and increase of student attention to cram school as a balancing between responsibilities and spheres of belonging (to some moral community) and achievement (in the physically displaced academic market defined by the cram school industry). Rather, for him and many students who end up at Musashino, there were processes of betrayal by teachers and alienation from peers.

When things first got difficult, I was able to get help from some of my friends, but this didn’t last. They abandoned me. I guess they were busy at first, but then they started to spend more time with the others who were also going to cram school. Cram school. That was all they talked about. How interesting it was, their teachers, what good friends they had there.15 At first, I wanted to go, but I began to see that it’s just more study. No reason to do more of that if you don’t have to.

It is not uncommon for students to strike out at teachers and classmates for violations of collective commitments to one another, at one time the foundation of the school’s moral community. This is balanced by self-blame for failure to keep up with the curriculum. Self-chastisement about how much work they should have done in middle school is also another familiar theme if students get to the second year of high school. (During the first year, they are usually still too angry to blame themselves or too bewildered to realize the full implications of being at such a low-level school.) Many become “ochikobore,” or those who fall to the bottom, like Tomo. Some remove themselves from the school, like Keiko. But unlike Sara and her elite classmates, the working-class students have no alternative paths for advancement, such as cram school. So for Keiko and other working-class students, removal from the middle school community (not talking to the teachers as much, not socializing with classmates, or in more extreme situations, skipping school) meant jeopardizing any chances to advance to a desirable high school. So, whether they leave middle school full of anger and resentment, or have already emotionally removed themselves from the contradictions of middle school, few enter high school with very high expectations.

High School Socialization

High schools in metropolitan Japan are fully class-sorted, with each school having a thin segment of the student population of the district. Thus, while middle schools most immediately confront students with the often rending process of internal stratification and sorting, high school confronts students with the result of that sorting process. If the primary purpose of middle school is to differentiate a heterogeneous population, the high school’s purpose is to solidify a homogeneous one. The curriculum plays a large part in this process.16 More than around any philosophy of education or development of community, the days, weeks, and months of high school are structured around the achievement of certain curricular goals. This is not much different from high schools in other national systems, but the structure of this curriculum is somewhat distinctive, resulting in different school cultures and different ways that class groups make sense of them. Usually, class theorists of education assume a sort of functionalist correspondence (e.g., as outlined by Bowles and Gintis 1976) between a curriculum and the future occupational requirements of students in the school. Thus, for example, a curriculum focused on abstract reasoning and synthetic problem solving will be found at elite schools that prepare students for future positions of authority and responsibility, while working-class curricula stress execution and repetition, the ability to follow orders. The Japanese school is based on the memorization of non-synthetic pieces of information, a high degree of fragmented knowledge, largely devoid of any analytical or synthetic operation, characteristic of what is often called a “deskilling” curriculum considered most suitable to manual labor (see Apple and Weis 1983 for a review). But unlike in many national education systems, this is the same national curriculum to which all students are subjected. The national curriculum in Japan is not differentiated into high and low tracks that work according to different principles, and while there are differences in pedagogy, it is probably high-level high school students who must spend the most time mastering this “deskilled” curriculum in order to pass the tests to enter the most prestigious universities. While some have pointed to this fact as evidence of equality, even democracy (Cummings 1980), others have argued (Horio 1988) that this form and the amount of work required to master it encourage adherence to rule and repetition, and engender attitudes of docility and uncritical receptivity across society. In any case, class differences do not seem to be primarily encoded in the formal curriculum.

In order to find how class differences are encoded into symbolic and social capital, we need to look at the way this curriculum is embedded in different, class-specific institutional contexts. As we have already seen, through cram school, elite students far more often develop strategies which improve their chances of high exam scores. In this case, class privilege is reproduced less through the informal conversation of home cultural capital than it is valorized through in-school evaluation. In Japan, economic capital is not converted in the strict sense into another form, but simply spent: spent on cram school where the knowledge of future tests and the strategies for passing them are gathered and sold by pedagogy specialists in the cram school industry.17 In fact, the highly segmented form of the curriculum lends itself to this form of purchase far better than the abstraction of “class codes” (Bernstein 1977) or “habitus” (Bourdieu 1977), both of which may be rather too complex for reliable transmission in most school settings.18 In this way, a curriculum that appears to be class-neutral (that is, in no way corresponds to differential patterns of home-culture capital form) actually becomes an even more efficient, if prosaic, vehicle for the reproduction of inequality.

Of course, this is not to say that the total experience of being in more elite schools, both public and private, does not differ in significant and systemic ways which reflect different patterns of class socialization. In fact, one of the distinctive characteristics of more elite schools is that they do not have to follow or rely on the formal curriculum as much as more middle-level schools do because their students will be looking to their cram school to pass the entrance exams. This allows teachers at more elite schools to read whole novels, in Japanese and English class, organize debates over the causes of World War I, or have more experimental labs in chemistry — none of which will directly improve students’ chances on the entrance exams. These clearly contribute to class-specific habitus, but unlike in educational systems in other countries, these differences are less encoded in the formal curriculum.19

This formal curriculum thus does not demand understanding (how do you “understand” a multiplication table or a list of the longest rivers in Europe?), but it does require hard work strategically directed at and justified by the promise of passing entrance exams. Sara’s classmate explained the thinking of many students at elite schools: “What we study is not really something you can ‘understand’ (rikai). You just memorize. That’s okay because if we had to understand it all, we could never pass the exams.” High school is a means of moving to another level, to college for elite students such as Sara, and mastery of the seemingly arbitrary bits and pieces of the exam curriculum is the means to that end. Maximization of this opportunity by students is not easy but is essential for success. Sara’s classmate continues: “It is hard work, tons of work, but if you don’t do it, you won’t get anywhere. And then, why are you in school?”

Working-Class High Schoolers Preparing for College Entrance Exams Never to Be Taken

Students preparing for exams. |

The situation at low-level high schools such as Musashino is dramatically different because virtually none of the students will even be taking college entrance exams. And if they are not going to take entrance exams, then what are they doing in school, which is built around preparation for these exams? At a bottom-level school such as Musashino, few students find any meaning in attempting to master the high school curriculum because where they go after Musashino and the knowledge and skills required for their future jobs will be very little affected by what they do at Musashino. It is not just that what is taught at these schools is unrelated to their future or the skills required by the world of work. It is that in order to enter the institutions that they will enter (trade schools or the workplace) no exams are required. This is not a mystery to Musashino students, who see their elder siblings, friends, and school sempai drifting into the low-level service sector of the economy. They quickly realize that they have very little chance of translating good school performance into a desirable job.20 And this situation has not changed much recently. Despite the years of deregulation of education and reduction of required courses, yutori kyōiku (“relaxed education”) and jiyūka (“liberalization”), supposedly to allow each school to more sensitively cater to the particular needs of their own student body, this has not made the curriculum any more relevant or suitable to the students at Musashino. Said one teacher,

Our students have always been so far below any sort of national standards that those sorts of policies have no meaning for us. When they stopped having classes on Saturday all it meant was less suffering for us and the students. We are not trying to meet any standards. The only thing that we try to do is finish whatever textbook we ask the students to buy. They don’t like to spend money on books that we don’t finish, and I can understand that.

If there has been any consistent pattern of change to which teachers at Musashino point, it is less a function of any Ministry of Education reforms than it is to do with the reduced preparation of the students entering high school and their reduced learning. One teacher, who had worked at Musashino for more than 10 years, explained: “While we hear about other schools increasingly teaching exam-oriented lessons, the real change for schools at the bottom is that we are being forced to accept lower and lower standards of passable work.”

To cite one example, Keiko told a story from her 2nd-year English class. The test was a translation from English into Japanese of a passage on Australian culture. All of the students were taught the English passage and its Japanese translation and were given a copy of each to study. When the day of the test arrived, they were given the English and asked to translate it. The teacher recorded their grades, and those students who did not get a passing grade had to take the test again, and then again, and then again, until they could produce enough of the Japanese to get a passing grade. This took a couple of weeks, as some of the students’ scores went down in their subsequent attempts. Finally, the teacher began to give partial tests — where a student was tested on only a part of the passage at a time. This sped things up, finally allowing the last few stragglers to complete the passage one sentence at a time. They would stand out in the hall memorizing the Japanese sentence and then rush into the teachers’ room, and often without even looking at the English, scrawl the memorized sentence as fast as they could before it slipped away. The teacher was embarrassed about this compromise, but defended his approach this way:

I know that they don’t learn the English in this way, not really. In fact, most of them don’t understand the Japanese [that they translate into]. I also know that they don’t need to study English. But they need to pass because they need to graduate, and if memorizing the lesson bit by bit will allow them to do that, that’s okay with me. It’s [the curriculum] all in pieces anyway, so it’s not really very different [from the rest of the lessons]. For a school like Musashino, it’s what we have to do. Otherwise, everyone in the class fails. For students like ours, that means they cannot get a job. They at least have to graduate. I’m not going to fail them.

Clearly, in this instance, students did not expand their understanding and mastery of the subject matter. They were also not working for some personal advantage. They were not maximizing anything, like their more elite peers. Having no stake in the outcome, they had no stake in the process. And the teachers, of course, were not deluded enough to imagine that they did.

But the students were learning something that did prepare them for their future: a form of work that was both distinct to their low-level, working-class school and that in some way “prepared” them for their next step. They did not learn logical reasoning nor did they have to take responsibility for their own learning, in the way we might associate with elite jobs. Nor did they learn the unquestioned obedience to authority one might associate with an ethic of factory work in Western theorizing on working-class culture in industrial capitalism. The cultural forms that often characterize class trajectories elsewhere are not replicated in today’s Japan nor are they meaningful to the ways in which these young people are situated within the Japanese service economies. What’s more, the students did not learn something more distinctively “Japanese” about collective responsibility or the moral community of group living. Instead, Musashino students learned how to perform clearly demarcated tasks, not for some meaningful if remote goal, but for the sake of completing it because they were asked to. Not in an oppressive atmosphere of strict obedience or conflict, but a sort of going through the motions of what we might call “dry” living. One very experienced female teacher characterized her students and what they learned in this way:

You watch the kids coming to school, going to their classes, talking to us and to each other. Of course, they learn to do the things that they’re supposed to do, and they do most of what we ask them to do. We don’t have much verbal fighting and no actual school violence [like the teacher’s schools in the 1970s and 1980s]. But that’s because violence would take too much energy. They call the US school a “shopping mall” high school, right? Well, this is more like a “convenience store” high school. 21 We should have them punch in the time clock and wear a 7/11 logo. Some people say this is not what school is supposed to be like. But here, at Musashino, that is what school is like, and we are luckier than we were before.

When students were asked to comment on this characterization, some pointed out that “there are some differences: you can’t sleep when you work the way you can in class.” When one student said that you do get money from working, and you have to pay to be in school, another pointed out, “Yeah, but it’s not much money in either place.” On the whole they thought the comparison was quite apt.

The Vacuum of Authority and the Politics of Its Delegation

An advert for the video version of the popular Be-Bop High School. Many students and parents unfamiliar with Musashino cited this as an example what it probably is like. |

Group living is a cultural context that shapes individual subjectivities in line with the moral and practical expectations of adult society, and as such, it is an important part of whole-culture socialization, an important part of learning how to participate in a wide range of institutional contexts. But as noted above, it is at the same time a management strategy, a form of governance that allows social control to be legitimately secured. Securing order is clearly an important consideration for teachers at any high school. But more than that, the sort of order and control, the representation of legitimate authority and consent, provides a context within which students learn how to define themselves, their peers, and those around them.22

In the more elite institutions, somewhat paradoxically, an ethic of utilitarian maximization and the displacement of the high school by the cram school as the primary terrain of competition enable the school to be a more manageable and relatively conflict-free zone. Students do not have to depend upon their teachers or compete with their peers as much as those students who are less able to access cram school. Still, the assumed importance of academics, and maybe more significantly, the relatively unquestioned patterns of participation that structure the practices of schoolwork support willing cooperation in an orderly classroom. Elite schools are able to secure sufficient legitimacy to order and facilitate the various non-academic parts of the school. At most elite high schools, most students show up at sports day, participate to some extent in coordinated club activities, and allow teachers to maintain sufficient institutional authority to control the class. Musashino teachers cannot assume the same level of willing participation or cooperation from students. Neither the instrumental value of grades nor the academic orientations apply in the case of Musashino students. By definition, these students are those who failed to demonstrate such abilities and orientations — otherwise they would not be at Musashino in the first place. This is combined with the virtual meaninglessness of an academic curriculum, leaving working-class high schools without any coherent center. Missing is the primary mechanism that establishes daily routine, motivates students, and helps teachers establish their authority around some model of orderly social control, some pattern of legitimate governance. When students have no reason to be in school, making their time in school meaningful is quite difficult.

When the more abstract problem of “why the students are in school” finds no real consensus among teachers at the bottom-level schools, they have the more immediate problem of how to secure order and functional respect. A mid-career teacher, who lamented being transferred down from a much more elite school, commented:

My students [at Musashino] see us as babysitters, or entertainers, or cops. There’s no link between what we do [teaching] and how the students respond to us. They might like me or not, but it’s sort of a personal thing, completely separate from what we’re doing here — education. If they like me, they’ll usually behave well. If they don’t like me, then I have problems.

We see continuity from middle school: working-class students seem more likely to seek out personal rather than instrumental relationships with their teachers, whether they are rewarded if they find them or frustrated and angry if they do not. The wet relationship with teachers is echoed in each condemnation as well as each tribute. Musashino students in fact depend upon teachers to help them in all sorts of important ways, besides keeping them from failing out of school: pregnancies, police trouble, drugs, family violence. Teachers are thus important people in many of their students’ lives. Nevertheless, this sort of closeness, even intimacy in a way, does not help teachers turn the school into a coherent place of social order and control. After all, daycare, stage shows, and jails (those places where babysitters, entertainers, and cops are found) are not necessarily appropriate places for high school adolescents. Teachers at working-class schools must turn elsewhere for models of order and authority. While the predicament is rather distinctive to working-class schools, the ways of dealing with it vary. One important variable is the political orientation of the teachers, a fact that reminds us of the way that class sorting is never separated from its political implications. The somewhat paradoxical fact is that both of these alternatives are in some senses based on an attempt to resuscitate the embattled models of group living.

Teachers’ union demonstration opposing revision of the education law. |

At Musashino, I saw two options that were familiar to most teachers and present, in some form, at most schools. The first is defined by the teachers who were active members of the teachers’ union. Almost 70% of the teachers at Musashino in the early 1990s were active members (a figure that was to drop to a dysfunctional rate of almost 10% in a few short years).23 Musashino was once considered a “union castle” (Rohlen 1977), a problematic school at the bottom where many of the more troublesome union teachers were sent in order to “contain the problem,” as the vice principal of Musashino once explained to me. If these teachers could organize a voting block or critical mass, they would be able to run the more important committees in the school. Ideologically, this group saw post-war education as kanri kyōiku, or “managed education,” that was too focused on control of both what students were taught and how teachers taught it. Some teachers argued that these practices violated both groups’ human rights (Horio 1988). The union teachers were critical of “group living” models as methods of control, and instead were committed to an education that was more consistent with principles of individual liberty and self-realization both in the content of their lessons and in the management of their classes. Pedagogically, these teachers were very critical of the Ministry of Education curriculum and its implementation, instead advocating a more open, even dialogical style in the classroom, more problem-solving tasks rather than tests, collective group projects rather than individual evaluation, and in the words of one student, “lots and lots of discussions — no matter what, we would have a discussion.” These teachers often attempted to remove themselves as the source of authority, and at times, as a target of student resistance, in ways that resembled a variation on “soft authority.” As one union teacher explained, “Unless the students know why they’re doing what they’re doing, it doesn’t have any meaning. They must come to some understanding.” These classes generated little direct conflict with students, although other teachers in the school criticized these union classrooms as unfocused to the point of anarchy, places where “no teaching was going on.” The union teachers believed, however, that this was a far more effective way to promote learning.

The non-union group of teachers was more conservative. The Tokyo Board of Education often placed ambitious, middle-aged teachers in the post of principal of these “union castles,” with the perceived mandate to quell or at least obscure the most obvious signs of union activity. Many principals saw this posting, even if there were virtually no substantial results, as a stepping stone out of teaching and into the administrative structure of the Board of Education itself. Not knowing much about the school, they took their short rotation (usually just a couple of years), hoping to be able to rally enough of the more conservative teachers around them. According to these principals and teachers, since Musashino students were not “leader” types, it was important for them to learn how to be “useful to society” (shakai ni yaku ni tatsu). This usually meant teaching them a somewhat different variant of “group living:” how to mold one’s own behavior to the needs of the group. More concretely, this was achieved through instructing them in greetings (aisatsu), use of appropriately polite language, and demonstration of an open (sunao) character in their willingness to do hard work and obey superiors. As one teacher explained, “Our students at Musashino are going to be doing jobs that anyone could do. They will require virtually no knowledge or skill. So, unless they can be taught to behave, they won’t be of use to society, or to themselves.” Pedagogically, these teachers were especially strict with students, with classroom conflict ever present, bubbling up into direct confrontation and disciplinary action daily. Some teachers within this group exploited the segmentation of the curriculum to codify classroom behavior into similarly discrete and therefore calculable variables. Thus, just as the exam might ask students to recite the five longest rivers in Europe, a teacher would grade each student on proper execution of the five steps for entering a room (call out, wait for acknowledgment, move to one’s seat, bow, and sit down). Other teachers who were less meticulous and had more of a stomach for open conflict demonstrated a more explosive classroom culture, where students were frequently and often arbitrarily berated and punished for their ill-defined failings in comportment and attitude.24 The second approach depended upon the unpredictable and uneven application of rules as weapons in confrontations that were often as personal as they were institutional.

These two approaches are broadly familiar to most public school teachers as addressing the structural and class predicaments of low-level schooling across Tokyo, and probably urban Japan more generally. Despite their diametrically opposed approaches, and the high level of antagonism between the groups, both groups were trying to combat the “drying out” of the moral community that was particularly developed at the working-class school. And, in their own way, they were both trying to restore some aspect of this moral community, of group living (the delegation of responsibility to students by the union teachers and subjugation of personal goals to the needs of the group for the more conservative teachers). The image of this “drying out” was vividly represented by a nearby high school that was organized around a “credit system” (tan’isei) where students had no homeroom and no coordinated collective activities. Students showed up to school and took enough credits, mostly in applied subjects, to graduate, as one might in college (or most US high schools). One union teacher complained that “the students might as well take a correspondence course. The Board of Education is just processing students.” His conservative adversary said, “Those sorts of places are not schools. They don’t teach their students to become anything at all.” This school’s abandonment of the school as a moral community, as part of the comprehensive education of students for adult society, was virtually unimaginable to these two groups of Musashino teachers, liberal and conservative, both committed, if in their different ways.

It is not surprising that, given the choice, students favored the less confrontational union teachers (except for those few who looked forward to a fight, like Keiko), but even this was not an unproblematic format. For Tomo, who had done so badly in the increasingly academic curriculum of middle school, the union teachers’ alternative to the regular curriculum was no more successful. He explained:

It’s easier just to study the textbook and fill out worksheets, even if you have to also be trained [as in the conservative teachers’ way]. Even if I don’t understand, it’s still better. Sitting there trying to have a discussion about something or other [in the union teachers’ class] was meaningless. They should have just prepared a lesson and taught it, but I guess they didn’t care enough to do that.25

Another student captured a predominant view of the more conservative teachers when she said that “they simply did not like students, and they probably did not like teaching. They were more concerned about catching and punishing us than teaching us anything.” Another student commented similarly about the union teachers: “They didn’t even care about us enough to try to catch us.”

For almost everyone, especially in their first year, the competing classroom cultures made for contradictory messages about school expectations, and students were often caught in the crossfire. Said Keiko, “At times, it got so bad that every class, every day was so different that you never knew what to expect. All the teachers were pushing you in different directions so that even if you wanted to stay clear [out of trouble], you could not.” Keiko, who in her first year prided herself on being able to go toe-to-toe with any teacher in the school, explained that “even though none of those teachers were able to fight me, after a while, you just get worn out. It’s not worth fighting anymore. I just moved away.” She added, almost puzzled, “And they let me go.”26 You have to have more at stake than most of the Musashino students did to function within, or in opposition to, this sort of school culture. By their last year, most students had learned to hunker down and keep their head out of the line of fire, and most teachers had lost much of the ambition or energy to bring any wet coherence to the moral community of the school. As students got older and increasingly began to see the school as less of a reliable mechanism for their future, they simply did not have that much at stake.

Today, many of the older teachers say the same thing about their schools and even their younger colleagues. The union is largely absent as a political force in the school (and in society) and unable in most schools to secure numbers sufficient to propose and execute any coherent alternative to the “control education” of the Tokyo Board of Education. The more authoritarian teachers have survived as clusters at some schools with reputations for troublesome students, but without the oppositional union teachers to fight against, they seem to be less self-consciously organized at most schools. Today, many teachers from both extreme groups lament the current state of education, not as too progressive (although there does seem to be more of a presence of counseling approaches) or too authoritarian (although incidences of some forms of school conflict do seem to be quite high). Instead, both groups report that education has lost its relevance as a shaper of young people’s character. The possibility of any moral community, however one sees the politics of group living, is probably most directly challenged by the threat of the dry convenience-store high school. On the other hand, maybe it is particularly well-suited to the needs of today’s labor market.

Occupational Self-Selection