Public school teachers in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona have won meaningful salary gains for themselves, and in several cases other school workers, and real although limited increases in education spending. Unfortunately, their demands for significant tax reform, including new taxes on corporations and the wealthy to fund a more general increase in public services, remain largely unfulfilled. Hopefully, the lessons learned and the connections made will lead to more democratic and powerful unions and worker-community movements for change that can carry the fight forward.

Teachers deserved a raise

Teachers definitely deserve a raise. A recent Economic Policy Institute study by Sylvia Allegretto and Lawrence Mishel finds a substantial and growing wage and compensation gap between what teachers and other similarly educated workers earn. For example:

- Average weekly wages (inflation adjusted) of public-sector teachers decreased$30 per week from 1996 to 2015, from $1,122 to $1,092 (in 2015 dollars). In contrast, weekly wages of all college graduates rose from $1,292 to $1,416 over this period.

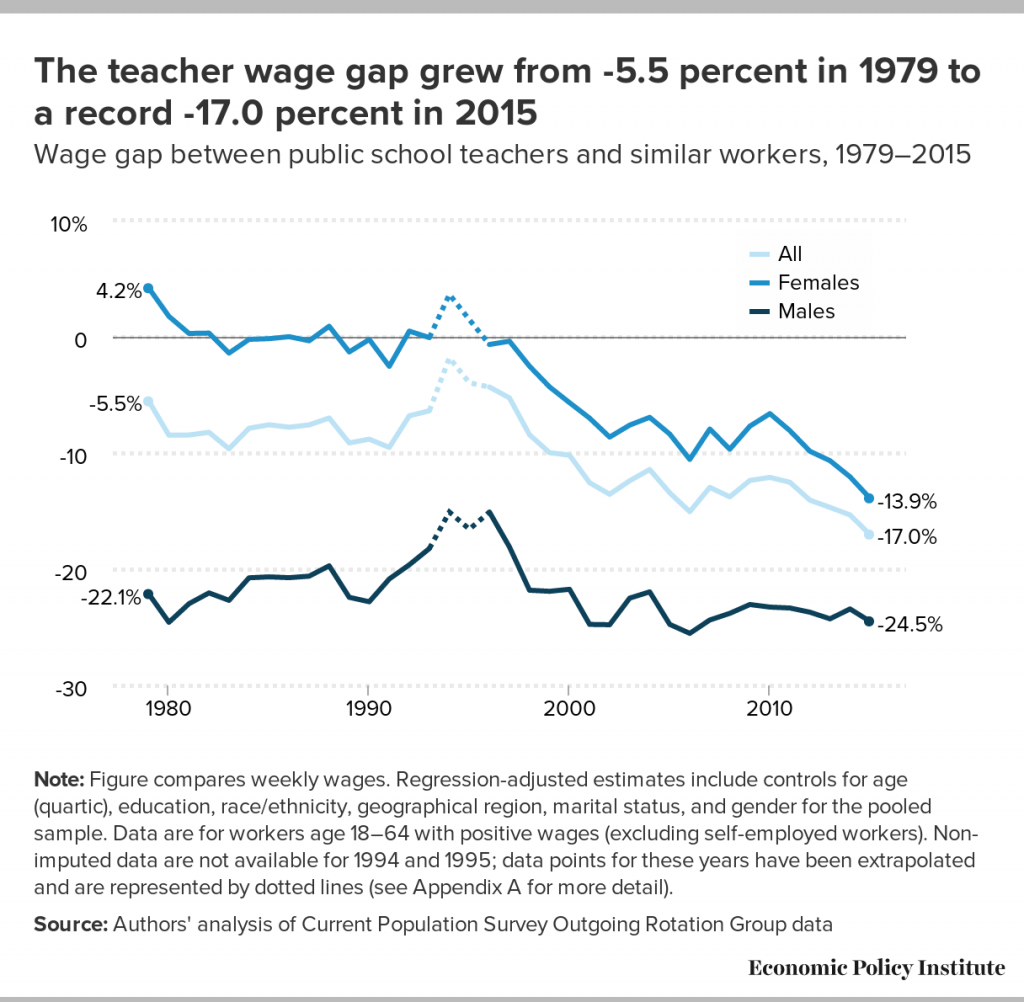

- For all public-sector teachers, the relative wage gap (regression adjusted for education, experience, and other factors) has grown substantially since the mid-1990s: It was ‑1.8 percent in 1994 and grew to a record ‑17.0 percent in 2015.

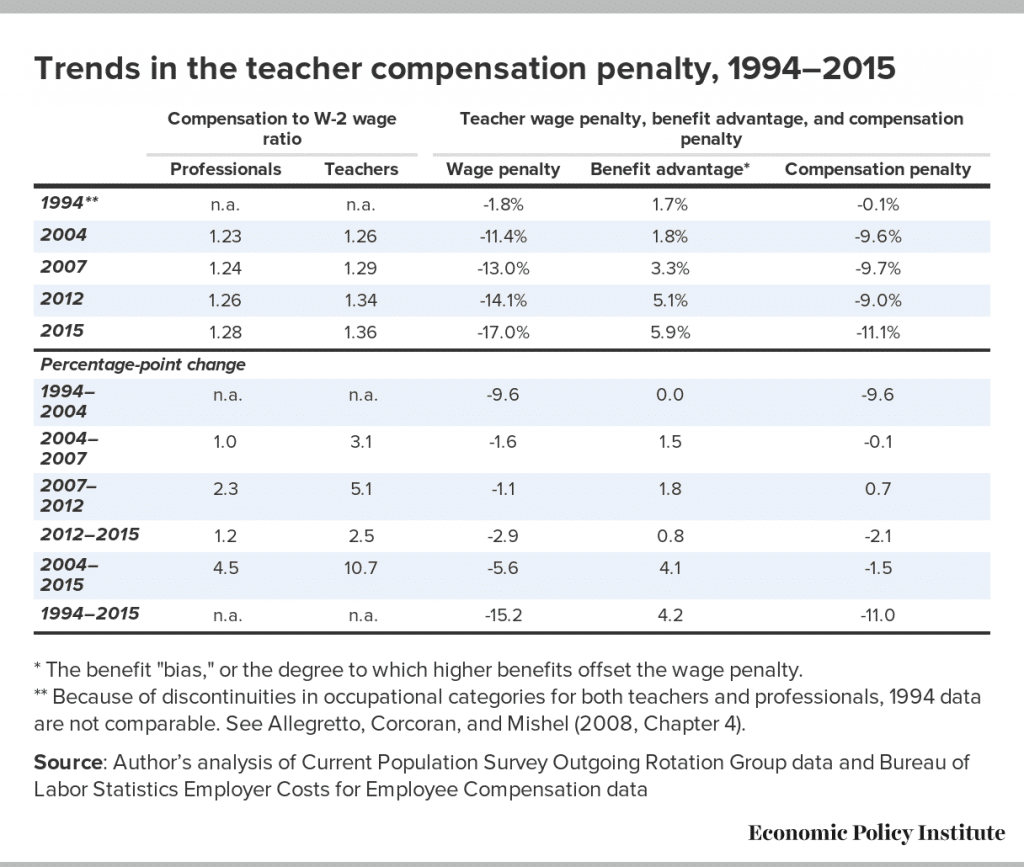

- While relative teacher wage gaps have widened, some of the difference may be attributed to a tradeoff between pay and benefits. Non-wage benefits as a share of total compensation in 2015 were more important for teachers (26.6 percent) than for other professionals (21.6 percent). The total teacher compensation penalty was a record-high 11.1 percent in 2015 (composed of a 17.0 percent wage penalty plus a 5.9 percent benefit advantage). The bottom line is that the teacher compensation penalty grew by 11 percentage points from 1994 to 2015.

- Collective bargaining helps to abate the teacher wage gap. In 2015, teachers not represented by a union had a ‑25.5 percent wage gap—and the gap was 6 percentage points smaller for unionized teachers.

The figure below highlights the growing wage gap between public school teachers and similar workers (controlling for age, education, race/ethnicity, geographic region, marital status, and gender).

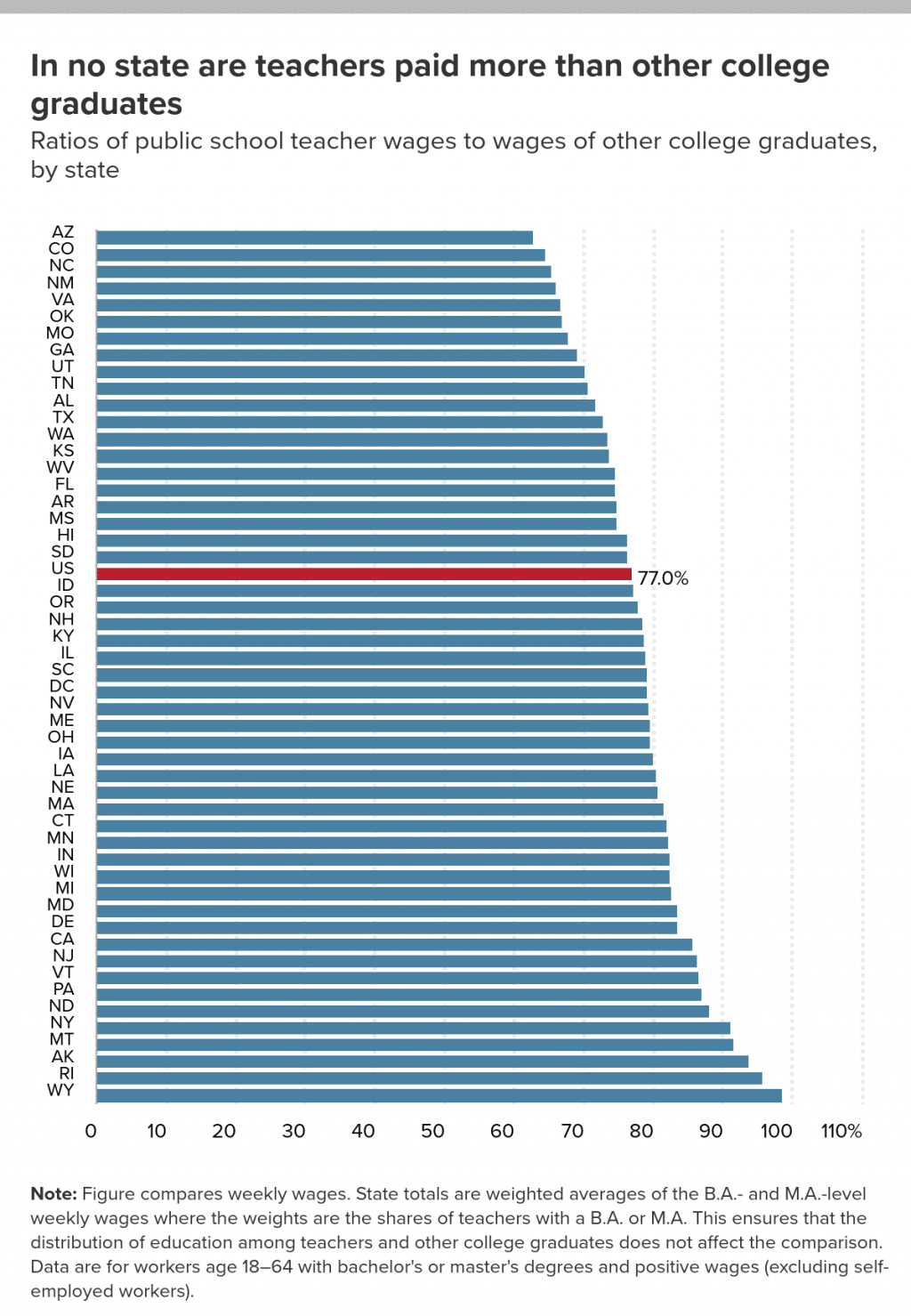

The next figure shows that in no state are teachers paid more than other college graduates. In fact, as the EPI study points out:

The ratio for the overall United States is 0.77, meaning that, on average, teachers earn just 77 percent of what other college graduates earn in wages. . . . In 18 states, public school teacher weekly wages lag by more than 25 percent. In contrast, there are only five states where teacher weekly wages are less than 10 percent behind.

And, as the table below makes clear, teachers suffer an overall compensation gap, with their benefit advantage not nearly big enough to compensate for their large and growing wage penalty.

The rightwing playbook

Teacher victories in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona were made possible by strong community support for their strike actions. However, teachers and other activists need to prepare for the likely rightwing counter attack, which will aim to break the newly created bonds of solidarity and support for collective, militant action.

A Guardian newspaper article, which includes a secret three-page manual on how to talk about teacher strikes produced by the State Policy Network, sheds light on rightwing fears and planning. The State Policy Network is “an alliance of 66 rightwing ‘ideas factories’ that span every state in the nation,” that is well funded by, among others, the Koch brothers, the Walton Family Foundation, and the DeVos family.

The manual talks about the need to discredit the strikes by portraying them as harmful to low income parents and their children. But it also recognizes that this is a challenging task. For example, it says:

A message that focuses on teacher hours or summer vacations will sound tone-deaf when there are dozens of videos and social media posts going vital from teachers about their second jobs, teachers having to rely on food pantries, classroom books that are falling apart, paper rationing, etc. This is an opportunity to sympathize with teachers, while still emphasizing that teacher strikes hurt kids. It is also not the right time to talk about social choice—that’s off topic, and teachers at choice-schools are often paid less than district school teachers.

As to what should be said, the manual encourages rightwing activists to respond to concerns about insufficient school funding by calling for more efficient use of existing monies, in particular by reducing “administrative bloat” and “red tape.” And, it has special advice for those that live in states where taxes have been recently slashed:

That is obviously a challenging message to counter. But you can consider something like,

One of the most important things we can do to make sure our schools are properly funded is to have a strong economy where everyone who can work can find a job and contribute to the tax coffers that fund the government. Lower tax rates help contribute to stronger job growth. Also lower taxes on individuals let teachers keep more of the money they earn.

More dangerous are some of the ways in which the rightwing actually seeks to punish or intimidate teachers. Jeff Bryant, writing at OurFuture.org provides a sobering list:

Leading into the two-day teacher walkout in Colorado, Republican legislators introduced a bill that would lead to fines and potentially up to six month’s jail time for the striking teachers. The bill was pulled, when it became clear even some Republicans weren’t too keen on the measure.

In Arizona, a libertarian think tank sent letters to school district superintendents threatening them with lawsuits if they didn’t reopen closed schools and order striking teachers to return to work. It’s unclear how or whether the threat will actually be carried out now that teachers are back on the job.

In West Virginia, where teachers used a nine-day strike to secure a five percent raise, Republicans have vowed to get their revenge by cutting $20 million to Medicaid and other parts of the state budget to pay for the increase. No doubt, when the axe falls on these programs, Republican lawmakers will be quick to blame the “greedy” teachers.

In Kentucky, Republican Governor Matt Bevin accused striking teachers of leaving children exposed to sexual assaults or being in danger of ingesting toxic substances because teachers weren’t at school. Now that the uprising has ended, Bevin has turned his revenge against teachers into an effort to take over the largest school system in the state and take away local control of the schools.

No doubt, this is just the beginning, which means that activists need to move quickly to build on victories and expand their challenge to existing relations of power.

The challenges ahead

One hopes that teacher activists in states where strikes have taken place are finding ways to build upon recent mobilizations to build organizations and revitalize their unions. And, that they are also reaching out to other public sector unions, with the aim of building a broad alliance that can spearhead a grass-roots movement for new progressive taxes and a more class conscious vision of state policy. Despite the dangers, this is a hopeful political moment for all of us.