In international human rights law, a “forced disappearance” occurs when a person is secretly abducted or imprisoned by a state or political organization (or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organization), followed by a refusal to acknowledge the person’s fate and whereabouts, with the intent of placing the victim outside the protection of the law.

From the exhibit web page: “The forty-three figures in the art installation by Toym Imao represent those left behind by victims of forced disappearance. Empty and hollow, each figure represents a year since Martial Law was declared in the Philippines. Instead of portraits and picture frames, the figures hold empty niches, signifying death, the lack of closure, the emptiness, the hollow feeling, and the gut-wrenching pain those left behind must deal with.”

The most infamous forced disappearances have occurred in Spain (during and after the Civil War), Chile (after the coup by General Pinochet in 1973), Argentina (during the so-called Dirty War from 1976 to 1983), and the United States (as part of the so-called War on Terror).

Now, Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers (“Expanding Work Requirements in Non Cash Welfare Programs“) is attempting to carry out a forced disappearance of poverty.1

The aim of the Council’s report is to make the case for “expanding work requirements among non-disabled working-age adults in social welfare programs.”2 In order to do so, the authors of the report attempt to show that (1) there is a large pool of non-disabled working-age adults who are currently beneficiaries of the three major non-cash welfare programs (Medicaid, food stamps or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and housing assistance) who can and should be put to work, (2) independence or self-sufficiency is undermined by participation in government anti-poverty programs, and (3) government assistance to the poor has become outmoded because poverty itself has virtually disappeared in the United States.

We’ve seen all these moves before. As Jim Tankersley and Margot Sanger-Katz explain, the numbers of adults who are beneficiaries of welfare programs but not working are likely exaggerated. For example:

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculated this year that three-quarters of food stamp recipients work within a year of participating in the program. That report suggests that Americans often use assistance programs as bridges to a new job, after they have lost previous employment.

The administration’s numbers may be particularly exaggerated for Medicaid. Under the Affordable Care Act, many states expanded their Medicaid program in 2014 to include more childless adults whose incomes bring them close to the poverty line. But the report examines adults who were enrolled in Medicaid in 2013, before the expansion, when most adults who were signed up were either pregnant women, the parents of young children or adults with extremely low incomes.

According to the council, about 53 percent of adult, non-disabled Medicaid beneficiaries worked less than 20 hours a week. Using a different set of government data from 2017, the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that 62 percent of such people had full- or part-time jobs. Another 18 percent lived in a household with another working adult. Council officials say the data set they drew upon, while older, is a better measure than the one Kaiser used.

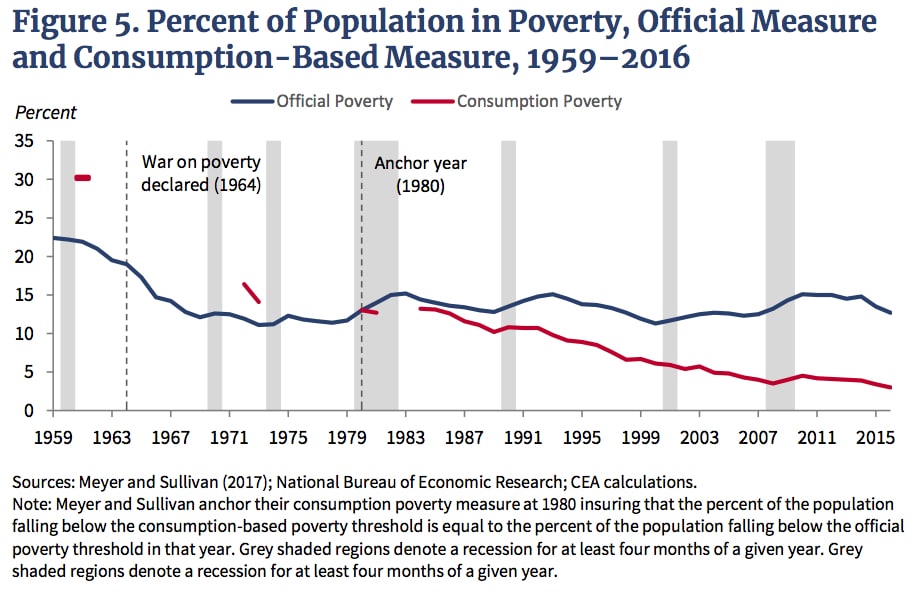

Then there’s the argument about the extent of poverty in the United States. While the government itself reports that poverty is still a large and persistent problem within the United States (since according to the official definition the poverty rate in 2016 was 12.7 percent, and the rate according to the Supplemental measure was 14 percent), the Council chooses to redefine poverty in terms of consumption (based on the work of, among others, Bruce D. Meyer and James X. Sullivan).

And, voilà, poverty is disappeared!3

Finally, they invoke the shibboleth that expanded work requirements respect and reinforce “independence” and the “dignity of work.”

Back in 2012, I suggested we need to contest the meaning of dependence:

In particular, why is selling one’s ability to work for a wage or salary any less a form of dependence than receiving some form of government assistance? It certainly is a different kind of dependence—on employers rather than on one’s fellow citizens—and probably a form of dependence that is more arbitrary and capricious—since employers have the freedom to hire people when and where they want, while government assistance is governed by clear rules.

We can also deconstruct the term by turning it around: why is receiving non-cash benefits from the government a form of dependence but cash distributions of the surplus—to large corporations and wealthy individuals—supported by a wide variety of government programs, is not?

As for the so-called dignity of work, I can only repeat what I wrote just a couple of years ago: what advocates of getting people back to work,

choose to overlook or ignore is that, in a world in which the majority of people are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to someone else—in which, in short, labor power is a commodity—there’s no necessary honor or dignity in work. It’s a necessity, born of the fact that people need to earn an income to purchase commodities to sustain themselves and to pay off their debts. And the most likely way to earn that income is to sell their ability to work to a small number of other people, their employers, who in turn get to appropriate and do what they will with the profits.

As I see it, the attempt to disappear poverty is actually a thinly disguised effort to discipline and punish the poor and to convert everyone—poor and non-poor workers alike—into a giant machine for producing surplus for the benefit of a tiny group of employers and wealthy individuals.

Perhaps we need to follow the example of the mothers of Argentina’s “desaparecidos,” who 40 years later are challenging the government’s attempt to erase the memory of those terrible years and put the brakes on the continuation of trials. In the case of the poor working-class today in the United States, we need to make sure they and their deteriorating conditions of life are not disappeared and that a real anti-poverty program—a radical change in economic institutions—is enacted.

Notes

- ↩ Kevin Hassett (Chair, from the American Enterprise Institute, who was appointed by Trump and approved by the Senate in a 81–16 vote on 12 September 2017), as well as Tomas Philipson and Richard Burkhauser (both appointed by Trump), are the members of the current Council of Economic Advisers.

- ↩ Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin offered up his state to approve work requirements for Medicaid benefits. Once Federal Judge James E. Boasberg rejected the Department of Health and Human Services’ approval of Kentucky’s plan, Bevin announced that he would deprive Medicaid patients of dental and vision benefits, effective immediately. The Trump administration has just revived its efforts to let et Kentucky compel hundreds of thousands of poor residents to work or prepare for jobs to qualify for Medicaid.

- ↩ This comes just after the United Nations Human Rights Council published the report by Philip Alston, its Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, according to whom:

The United States is a land of stark contrasts. It is one of the world’s wealthiest societies, a global leader in many areas, and a land of unsurpassed technological and other forms of innovation. Its corporations are global trendsetters, its civil society is vibrant and sophisticated and its higher education system leads the world. But its immense wealth and expertise stand in shocking contrast with the conditions in which vast numbers of its citizens live.