In 1933, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany through the democratic vote. In 2018–85 years after the electoral victory of the Nazi leader–former army captain Jair Bolsonaro was elected President of Brazil with 57.5 million votes from an electorate of 147 million. His rival, professor Fernando Haddad, secured 47 million votes. There were 31.3 million abstentions, 8.6 million null votes, and 2.4 million blank ballots. Consequently, 89.3 million Brazilians did not vote for Bolsonaro.

Many wonder how it is possible, following the enactment of the Civil Constitution of 1988, and the democratic governments of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Lula, and Dilma Rousseff, that Brazilians have elected as president a shady federal deputy, openly in favor of torture and summary execution of prisoners, a die-hard defender of the military dictatorship that subjugatedthe country over 21 years (1964-1985).

Nothing happens by chance. Multiple factors explain the meteoric rise of Bolsonaro. Brazilian democracy has always been fragile. Since the arrival of the Portuguese to our lands, in 1500, autocratic governments have predominated. Under colonial rule, we were governed by the Lusitanian monarchy until November 1889, when the Republic was decreed.

The first two terms of our Republic were led by military men. Marshal Deodoro de Fonseca governed from 1889 to 1891, and General Floriano Peixoto from 1891 to 1894. In the 1920s, President Artur Bernardes governed for four years (1922-1926) through the semi-dictatorial State of Siege. Gertulio Vargas, elected president in 1930, became a dictator seven years later, until he was deposed in 1945.

Since then, Brazil has seen brief periods of democracy. Marshal Dutra succeeded Vargas who, by direct vote, returned to the Presidency of the Republic in 1950, where he remained until right-wing forces induced him to commit suicide in 1954. Power was provisionally occupied by a Military Junta, that transferred authority to Ranieri Mazzilli and, immediately, admitted the inauguration of João Goulart (Jango), vice president of Janio, who governed from 1961 until April 1964, when he was deposed by the military coup that imposed the dictatorship, which lasted until 1985.

In the last 33 years of democracy, one president died before taking office (Tancredo Neves); his vice, José Sarney, took over and brought the country to bankruptcy; an avatar, Fernando Collor, was elected as the “maharajah hunter” and two and a half years later was impeached for corruption, with the Presidency occupied by his vice, Itamar Franco. This was succeeded by two presidential terms for Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2003), two for Lula (2003-2011), one complete term for Dilma (2011-2014) who, re-elected, was also subjected to a clearly coup-driven impeachment after a year and eight months in office, replaced by her vice president, Michel Temer, who will hand over the presidential sash to Bolsonaro January 1, 2019.

ACHIEVEMENTS AND MISTAKES OF THE PT

How can it be explained that after 13 years of PT (Workers’ Party) government, 57 million Brazilians, among 147 million voters, within a population of 208 million, choose as president a low-ranking officer, federal deputy throughout 28 years (seven terms), whose notoriety doesn’t result from his parliamentary activity, but from his cynicism in praising torturers and lamenting that the dictatorship didn’t execute at least 30,000 people?

How to understand the victory of a man who, in his campaign speech in São Paulo, broadcast online, proclaimed loudly and firmly that, should he be elected, his opponents should leave the country, or they would go to prison?

This is not the time to “beat a dead horse.” However, even though the social advances promoted by PT governments carried considerable weight, such as lifting 36 million Brazilians from poverty, it is necessary to highlight errors that the PT has not yet publicly acknowledged and which, nonetheless, explain its political erosion. Of these, I highlight three:

– The involvement of some of its leaders in proven cases of corruption, without the Party’s Ethics Commission having penalized any of them (Palocci distanced himself from the Party before he was expelled).

– Neglecting the political literacy of the population and media favorable to the government, such as community radio and television stations, and the alternative press.

– Not having implemented any structural reform during 13 years of government, except for that altering the social security contributions system of federal operations. The PT is today a victim of the failure to promote political reform.

Dilma was re-elected with a small margin of votes over her opponent, Aecio Neves. The PT did not understand the message at the polls. It was time to ensure governability by strengthening social movements. It chose the opposite path. The economic policy of the opposition’s government program was adopted.

With Temer, the crisis deepened with millions unemployed; false GDP growth; labor reform contrary to elementary workers’ rights; 63,000 murders per year (10% of the world total); military intervention in Río de Janeiro to attempt to subvert drug trafficking control over the city. And corruption running rife in politics and among politicians, without even the President of the Republic being exempt, with photos and video evidence broadcast on prime time TV.

All this has contributed to deepening the political vacuum. Of the parties with the most seats in Congress, only the PT had a representative leader: Lula. Even when imprisoned, he enjoyed 39% support in the polls conducted at the beginning of the election campaign. However, the judiciary has confirmed the obvious: he was detained without evidence so that he would be excluded from the presidential race.

Then came Bolsonaro. How can the meteoric rise of the candidate of a tiny, insignificant party who, wounded during the campaign, abandoned the streets and didn’t participate in the televised debates, be explained?

I repeat, nothing happens by chance. The former captain received the support of three important segments of Brazilian society:

First, of the only sector that, in the last 20 years, has obstinately devoted itself to organizing and serving as the leadership of the poor: conservative evangelical churches. The PT should have learned that it never had as much national capillarity as when it had the support of the Ecclesial Base Communities (CEBS). But no grassroots work was carried out to expand this capillarity and train the party branches, unions, and social movements, except movements such as the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) and the Homeless Workers’ Movement (MTST).

Bolsonaro was also supported by a section of the military police that is nostalgic about the days of the military dictatorship, when it enjoyed broad privileges, its crimes were covered up by censorship and the press, and it enjoyed total immunity and impunity. Now, according to a promise of the president-elect, it will have a license to kill.

And he was also supported by sectors of the Brazilian elite that complain about the legal restrictions that prohibit their abuses, such as the agricultural business, and mining companies that covet indigenous reserves, and must respect environmental protection, especially of the Amazon.

There is also a new factor that favored the election of Bolsonaro: the powerful lobby of digital networks monitored from the U.S. Millions of messages were sent directly to 120 million Brazilians with Internet access, almost all voters, since in Brazil voting is compulsory for all citizens between 16 and 70 years of age.

Bolsonaro exploited this new resource that seriously threatens democracy, and was used successfully in the election of Donald Trump in the U.S., and in the referendum that decided the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union (Brexit).

FUTURE CHALLENGES

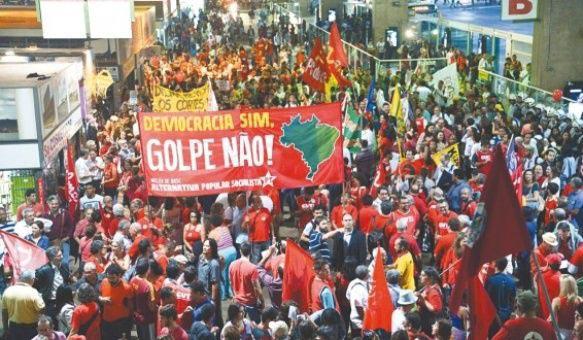

What to do now? Progressive movements and what remains of the left in Brazil will surely promote marches, demonstrations, petitions, etc., in an effort to avoid a fascist government. None of that seems enough to me. We have to return to the grassroots. The poor voted for the project of the rich. The left fills its mouth with the word “people,” but is not willing to “lose” its weekends to go to the favelas, to the villages, to the rural areas, to the neighborhoods where the poor live. These are the priorities at the current Brazilian juncture: that the PT conducts a critical self-evaluation and recreates itself; that the left resumes its grassroots work; that progressive movements redesign a plan for Brazil that is a viable political project. Otherwise, Brazil will enter the dark ages for a long spell.