Economics is unique among the social sciences in having a single monolithic mainstream, which is either unaware of or actively hostile to alternative approaches. (John King 2013: 17)

What does heterodox economics mean? Is the label helpful or harmful? Being outside of the mainstream of the Economics discipline, the way we position ourselves may be particularly important. For this reason, many around us shun the use of the term “heterodox” and advise against using it. However, we believe the reluctance to use the term stems in part from misunderstandings of (and sometimes disagreement over) what the term means and perhaps disagreements over strategies for how to change the discipline.

In other words, this is an important debate about both identification and strategy. In this blog, we wish to raise the issue in heterodox and mainstream circles, by busting a few common myths about Heterodox Economics–mostly stemming from the orthodoxy. This is a small part of a larger project on defining heterodox economics.

Myth 1: Heterodox Economics is Anything that is Not “Mainstream”

While it is true that many people do see the heterodox as defined in the negative–especially people observing from the mainstream and from outside the discipline–many scholars in the heterodox community also see the term as something positive and proactive, defined by a set of principles (see here for an interesting overview of definitions). The term dates back to the 1930s (e.g. Ayres 1936), but more recently definitions have been developed by Lee (2009), Vernengo (2011), Lawson (2013), and Dymski (2014).

Lee (2009: 8-9)–an important figure in building a heterodox economics community, particularly in the 2000s–saw heterodox economic theory as an “empirically grounded theoretical explanation of the historical process of social provisioning within the context of a capitalist economy”. For Lawson (2013, ch. 3), heterodox economics is best characterized by pluralism at the level of method, coupled with a declared ontology of openness, relationality process, and totalities, in contrast to mainstream economics which is characterised in terms of its enduring reliance upon methods of mathematical modelling, expressed in the mathematical deductivism and its ‘laws’ or ‘uniformities,’ interpreted as correlations or regularities.

Vernengo (2011) argues that heterodox economics is centrally about understanding reproduction of society, that the production and distribution of the social surplus is central for their theories, and that effective demand is valid in the long run (which means that the limits to accumulation are mostly political). Going back to classical political economy, distribution is determined exogenously by social and institutional conditions (e.g. the wage is determined by the bargaining position of labor and the rate of profit is influenced by the interest rate, which is influenced by the central bank).

Lee always encouraged students to do Economics in a pluralistic and integrative manner and to be responsible and open-minded economists. Openness to alternative methods also gives a much larger space for classes, gender, institutions, instability, uncertainty, exploitation, power asymmetries, distributional conflicts and ecological issues. In a similar manner, Mearman and Guizzo (2019) see heterodox economics as a pluralist community with a diversity of origins, purposes, and standards for economic reasoning, ranging amongst others from history and philosophy of economics, to modelling, community organising, and policymaking.

We see heterodox economics as a study of production and distribution of economic surplus, including the role of power relations in determining economic relationships, a study of economic systems, and tendencies associated with it, and the employment of theories that have these issues at their core, such as Classical Political Economy, Marxian Economics, Feminist Economics, Institutional Economics, and Keynesian Economics. As reality is not static, we deem it as crucial to constantly think and rethink the nature and appropriateness of these theories and methods.

Now, you may think these definitions are too complex, that defining it in the negative is just easier, more practical? Well, it turns out that is not straightforward either, as defining the boundaries for ‘mainstream’ Economics is not simple (see Cedrini and Fontana 2018).The American Economics Association defines the field as the study of scarcity, the study of how people use resources to respond to incentives, or the study of decision-making. Others yet define the mainstream by its method (see e.g. Dow 1997 or Bandiera in a recent Royal Economics Society lecture), which can in turn be distinguished from the open systems approach of the heterodoxy.

Recognizing that heterodox economists may be united in their critique of orthodox economics does not mean they are defined by this common position (in fact, scholars in many other disciplines also reject orthodox economics, but this does not mean they are automatically heterodox economists).

So is Austrian Economics heterodox? This is obviously up for debate, and many Austrian economists will indeed identify as heterodox solely on the basis that many of them are excluded from the mainstream or have a different understanding of categories such as equilibrium and uncertainty. However, many heterodox communities would not include Austrians on either epistemological (Austrians tend to adhere to marginalism, see e.g. Vernengo 2012) or sociological bases (they are not a part of our research communities, which includes academic institutions, journals, and conferences).

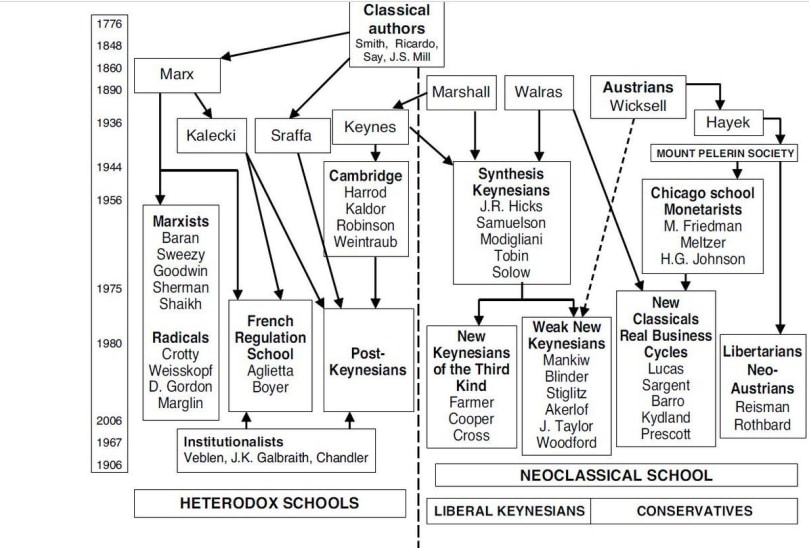

Table 1- Schools of Economic Thought – Source: Marc Lavoie’s Introduction to Post-Keynesian Economics.

Myth 2: It is “hip” to be Heterodox

The Economist once ran a story “Is it heterodox, or just hip?” (similar claims have been made elsewhere too, for example in Noah Smith’s 2016 Bloomberg piece). Well, yes, it is true that the use of the term has been on the rise in the 1990s and the 2000s (as documented by Jakob Kapeller in a 2017 edition of the Heterodox Economics Newsletter, see figure below). There are lots of books popping up using “heterodox” in their book titles. Lavoie (2014: 6) writes that “since the 1990s, but even more so since the mid-2000s, the term “heterodox” has become increasingly popular to designate the set of economists who view themselves as belonging to a community of economists distinct from the dominant paradigm”.

But an increased use of the term does not mean that heterodox work has been accepted in the core of the Economics field. There has not been substantial change in the field since the global financial crisis (see Mason 2018, Skidelsky (2018) and Steinbaum 2019) let alone more inclusivity or openess (e.g. in top journals, hiring practices, prizes or teaching). While there has been some self-critique within the mainstream (e.g. critique of DSGE by Romer 2016 and Blanchard 2018), this does not mean that alternative theories, such as Post-Keynesian theory or Marxian theory, are now considered to be valid economic theories by top Economics institutions. As Coyle (2013) observes, the financial crisis had little impact on how the academic orthodoxy in Economics is constructed and reproduced.

Meanwhile, since the crisis, it seems that many concepts developed within a heterodox framework have been incorporated and appropriated by mainstream scholars, adapting them to mainstream frameworks, without any acknowledgment of those concepts’ heterodox origin (as highlighted by Jo Michell, among others).

Heterodox Economics is getting traction outside of Economics, though. We can publish in top journals of other fields (e.g. Politics, Geography, Sociology, Philosophy, Development), we can get media coverage in The Financial Times (e.g. prominent heterodox scholars such as Mariana Mazzucato, Stephanie Kelton and Steve Keen), and we can get jobs at top universities, such as University of Cambridge, LSE and Columbia University–but outside of Economics departments (you tend to find heterodox economists at institutes, centers, management schools, and non-Economics social science departments). In the US, many heterodox economists end up teaching at liberal arts colleges. (Note that in some non-Western countries, heterodox economists may get jobs in top Economics departments as they are not as marginalized–this is for example the case in Brazil, see Dequech 2018).

It is true that Heterodox Economics is popular among students (e.g. Rethinking Economics), the public, and non-economists, but claiming that it is “hip” to be heterodox can be offensive to heterodox economists, as it suggests complete oblivion to the exclusion from our own field that we as heterodox economists historically have faced and continue to face. How many times has it not happened to us that someone within the dominant paradigm says:

Well, you’re not really doing Economics though…?

Myth 3: The Mainstream Is Already Heterodox

Some claim that the mainstream is already heterodox (e.g. Diane Coyle 2007, David Colander 2009, and Colander et al. 2010). These scholars argue that the inclusion of endogenous growth theory, behavioral and experimental economics, complexity economics and other theoretical innovations have reduced the dominance of neoclassical economics (for comprehensive responses to this claim, see Lee and Lavoie 2012, Thornton 2015 and Stilwell 2016). While these developments may give a perception of diversity within the mainstream, as Stilwell (2016) points out, the core still relies on neoclassical ideas such as methodological individualism and systemic stability produced through market forces. There may be a ‘cutting edge’ which breaks with some orthodox assumptions, as Vernengo (2014) puts it, but it is this part of the mainstream that allows the mainstream to sound reasonable when talking about reality and is therefore plays an important role in maintaining its dominance.

It is evident that there is some extent of pluralism in mainstream Economics, especially with regards to models and different forms of minor deviations from neoclassical economics (e.g. New Keynesian Economics, New Classical Economics, New Institutional Economics, Behavioral Economics). Nevertheless, it must also be acknowledged that there continues to be monism in terms of theoretical starting points, methodological approach, and in attitude to methodological alternatives (see also Dow 2008).

Critique of the field being met with the defense of the field’s already existing pluralism thus ignores the actual wide plethora of theories and methodologies that exist in Economics outside the mainstream. Furthermore, these theoretical innovations have not in any shape or form replaced neoclassical economics as the cornerstone of Economics curricula across the world, even if they may be taken as electives down the line in the course of an Economics degree. In short, the developments are neither radical nor transformative.

Myth 4: Heterodox economists are Just Lefties Upset with Neoliberalism

Often, the mainstream of the field is described as neutral, while the heterodoxy is described as ideological. Those believing in such a statement would be surprised to learn from Myrdal (1953) that the development of economic thought has always and everywhere been political, as politics and economics are closely intertwined. There’s a recognition within all heterodox schools of thought that Economics is inherently political. This does not mean all heterodox economists will agree on politics, but they will usually agree that market solutions do not lead to “natural” or “optimal” outcomes.

Dismissing heterodox Economics as a political project is common, which completely covers up the politicalness of mainstream Economics, and it assumes motivations among heterodox economists that they cannot prove or validate.This assumption leads The Economist journalists to conclude that heterodox economics is more of a “tantrum” than an actual rigorous intellectual alternative to the mainstream.

However, much of the heterodox critique of the strong bias towards market-based theory and policy runs deeper than a tantrum against neoliberalism or mainstream economic. It boils down to challenging the idea that the market can always lead to the best outcome. Why is the market solution to economic problems the only game in town and everything deviating from it about market failure? This question relates to the long-standing debate on whether or not economics is value free and how it is possible to best promote positive analysis over normative. While economists often attempt to disguise normative conclusions behind positive analysis, subjective factors are inevitably involved in the development of scientific ideas, and these are theory-laden because they are identified from the perspective of a paradigm. Furthermore, for many heterodox economist, this discussion is also about acknowledging pluralism. That is, there are different ways to investigate an economic phenomenon, and competing approaches, methods and theories lead to different policy implications.

Although mainstream economics and neoliberalism should not be seen as synonymous (see Naidu, Rodrik, Zucman, 2019), the assumption that economic decisions reflect free choice and individual preference tends to support conservative economic policy, which–combined with a focus on markets, incentives and market failures–ends up promoting and supporting market fundamentalism. In this process, core aspects of heterodox economics, ranging from power and conflict between labour and capital, to inequality and the role of institutions have been systematically neglected. It is, therefore, not a surprise to see the heterodox critique of neoliberalism overlapping with critique of mainstream economics.

With the above considerations in mind, it becomes clear not only that choosing one theoretical framework and excluding others is political, but also that every theoretical framework is political, including neoclassical economics. Since class conflict is a core element of much of heterodox economic theory, you will find heterodox economists being more explicitly political, as they are more likely to challenge the ethics of distribution within the system of social provisioning. However, as pointed out by Jo and Todorova (2015), most heterodox economists do not actually practice politics.

Myth 5: Heterodox Economists Will Take Over Once They Are Able to Construct Convincing Enough Models (aka ‘It Takes a Model to Beat a Model’)

This is perhaps one of the most ridiculous myths about Heterodox Economics, as it completely shies away from the political nature of our discipline. Several big names in the mainstream perpetuate this idea that Heterodox Economics is kept outside of the mainstream of the discipline because it is simply not rigorous or scientific enough (e.g. in an interview with the Financial Times Pontus Rendahl at University of Cambridge likens Heterodox Economics to creationists and alternative medicine). Angus Deaton has made a similar point, arguing that Economics must “be kept rigorous,” as if work done by Heterodox Economics is excluded based on its lack of rigor.

This myth is not only problematic because of its positivist and linear view of scientific progress, but we are also concerned with what ‘convincing modelling’ means. There is a vast range of models associated with heterodox economics. See for example, classical-Marxian models, such as Goodwin (1967), Foley (2003), Julius (2008), Tavani (2012), Zamparelli (2014); Kaleckian models, such as Bhaduri-Marglin (1990), Dutt (1984), Barbosa-Taylor (2006); Kaldorian, Harrodian and Post Keynesian models, such as Pasinetti (1962), Setterfield (2000), Skott (2008), Skott and Soon (2015); Thirlwall’s models, such as Vera (2006), Turner (1999), García-Molina and Ruíz-Tavera (2009); Stock-flow Consistent models, such as Lavoie and Godley (2006), Zezza (2004), Dos Santos (2006), Kinsella and Khalil (2011), Caverzasi and Godin (2015), Passarella (2012) and Dafermos, Nikolaidi, and Galanis (2017); and Agent-Based Models, such as Epstein and Axtell (1996), Tesfatsion and Judd (2006) – to mention a few!

Thus, putting aside the critique of modelling in economics, two questions come to our mind: first, which kind of rigour is claimed within [mainstream] economics? Second: why aren’t heterodox models accepted as sufficiently rigorous? The battle between the mainstream and heterodox is by no means straightforward. The rules of the games are contested and there is no impartial measure by which success is judged. Contesting the dominant measures of excellence are indeed among the core demands of many heterodox economists.

Following Myrdal’s (1953) insight that the development of Economics has always been political, it is clear that it is not simply a matter of constructing ‘better’ economic models. The political process is central. As Cohen and Harcourt (2003) observed in their review of the Cambridge Capital Controversy, for example, while Cambridge, Massachusetts lost the theoretical debate, they won the hegemony (this was even recognized by the Cambridge, Massachusetts side, see e.g. Samuelson 1966). Consequently, scholars working in the tradition of Cambridge, England are now excluded from the field (e.g. Post-Keynesians, Kaleckians, Sraffians, Marxians).

Furthermore, the official university research evaluation processes (e.g. the Research Excellence Framework (REF) in the UK) marginalize non-mainstream approaches, thereby operating to compound many of the problems mentioned so far (Lee et al. 2013, Stilwell 2016). As research evaluation programs favor mainstream Economics approaches over heterodox ones, teaching also suffers as lecturers hired by Economics departments seeking to maximize their REF score will likely hire only mainstream economists who are likely to publish in top journals (incidentally, Mearman et al. 2017 have found that teaching has changed little with respect to pluralism since the financial crisis, despite some claims to the contrary). Furthermore, monism in the mainstream makes it less likely that heterodox theories may be picked up by students or policy-makers, thus further compounding the already unfortunate situation. Finally, there have been several studies of the Economics field that show that it is among the most hierarchical academic fields (D’Ippoliti, 2018) and that social ties to editors are also important in determining whether a study is published, thus suggesting that success even within the mainstream is not based solely on their internal measure of rigor.

Myth 6: Heterodox Economics Is Not Really Economics Though

If Heterodox Economics abandons neoclassical assumptions and formal modeling, why should it be called Economics at all? Couldn’t it be a part of sociology? This was the argument made by The Economist. This view of Economics is ahistorical as it does not recognize that what is heterodox economics today was considered a part of Economics in the past. When Smith, Ricardo, Marx and Keynes did their economic work, they were acknowledged as being a part of the profession. They criticized each others’ arguments, assumptions, and theories, but they did not dismiss each other for not being economists. But their ideas have been excluded through a political process.

Ironically, the narrowing of mainstream economics and squeezing of heterodox economists into other departments has come with a push for increased interdisciplinarity. This has led to the odd situation where economists look for collaborators in sociology or politics departments, while maintaining strict definitions of who can be considered an economist. More often than not, economists will collaborate with other social scientists that work within similar traditions (e.g. rational choice theorists in politics or sociology), leading to a narrow form of interdisciplinarity. Further, adding political context or history to mainstream economic analysis does not make it heterodox. Rather than adding interdisciplinarity to social phenomena, we believe it is the nature of social phenomena that bear on the disciplinary or interdisciplinary methods and approaches that are required for their analysis.

Myth #7: Heterodox is too Confrontational. Can’t we Strive for Pluralism Instead?

Pluralism and heterodox economics aren’t synonyms. Pluralism is a methodological position that implies that competing theories should be taught alongside each other, be it heterodox or mainstream. Pluralism is not in direct opposition with the mainstream, but rather it tries to broaden the field of Economics.

‘Pluralism is an ‘in principle’ position, based on ontological, epistemological and ethical propositions (as discussed by Mariyani-Squire and Moussa 2013), whereas heterodox economics is an alternative way of approaching economic questions that stands as alternatives to the mainstream. Heterodox economists may well be pluralists in principle, as creating space for heterodox economics might in practice result in pluralism. However, fighting for pluralism may not be strategic if our goal is a paradigmatic shift within Economics (a point made on Twitter by Danielle Guizzo a few months ago).

The Difficulty of a Definition

Defining a whole field, such as Heterodox Economics is not easy, especially not in the social realm (see also Lawson 2015). As with other fields in social science, there will be some disagreement of the precise way to define it, and what kind of scholarship should be included.

Defining heterodox economics needs to be both practically relevant and historically grounded. Practically, it is broadly about seeking to render economics a relevant and inclusive discipline. Here, we don’t deny the issues raised by Mearman (2012) related to the need and motives for classification, and its consequences. That is, definitions of heterodox economics usually leads to “unwarranted dualism” where scholars create unjustifiably strict and fixed distinctions between the categories. While this might be a useful path to take due to the complexity of the object we are trying to define, it leads us to underplay its complexity for the sake for a simple and clear definition (see also Dow 1990).

Historically, the concept has been discussed, theorised and applied by a broad and diverse group, starting with Ayers (1936), and since then there have been contributions from economic methodologists (e.g. Hans 2011), historians of economic thought (e.g. Wrenn 2011), macroeconomists (e.g. Michell 2016), microeconomists (Lee 2017), and philosophers (Lawson 2006). This is important to understand, as while some might find the definition of the term ‘confusing,’ the source of the confusion might have less to do with the clarity and coherence of any single definition, and more to do with the multiple angles through which the term has been theorised.

With our definition mentioned above, we aim to identify the broader level of principles crossing the diverse discussions on what heterodox economics is. We believe it is important to have a positive definition of heterodox economics to distinguish the field from other social sciences, as well as from the mainstream of the field. Heterodox economists are not sociologists or political scientists, although we are outside of the mainstream of Economics and some heterodox economists may find themselves being employed by such departments. This leads us to our final point…

Why We Should Call Ourselves Heterodox

‘But we are all economists!’ some heterodox economists argue. Why signal that somehow we are different from them? However, we are not sure the ‘we are a big family of economists’ strategy is helpful–especially given that the majority of “our family” is excluding us from mainstream arenas. Such a claim indirectly assumes that there are not steep institutional barriers that negatively affect heterodox economists’ employment opportunities, funding chances, and their chances to impact the policy making process. The pejorative and dismissive tone towards heterodox scholarship exists, and the question that follows is what we are going to do about it. To avoid acknowledging both the fundamental differences and exclusion is to close door for the progress of the discipline and for young scholars, who are forced to reinvent themselves and find jobs in departments other than economics, contributing to the monolithic character of the discipline.

On a Twitter thread last year, many pros and cons of using the term heterodox came up. We do believe that so far, the pros outweigh the cons. As Stillwell (2016) puts it bluntly: ‘Labels matter […]. They construct imagery and signal strategic choices’. To us the label signals a strategic choice: Do we try to blend in and pretend that all is fine or do we speak up about the marginalization that is taking place in our field? Self-identifying as heterodox signals to the world that alternative analyses of economic relationships exist–if anything it reinforces the idea that there are different ways to do economics, a point that rests at the core of the argument for pluralism (a big [happy] family after all!). And importantly, it also helps to raise awareness about the fact that these perspectives have been actively excluded from the mainstream over a period of four decades or more.

Does accepting the term heterodox economics mean we accept our marginal disciplinary status? No. On the contrary, we use the term in order to challenge this marginalization. If people find the heterodox label confusing, we should be able to clarify where we are coming from. This is key if we want to change the current state of our profession. If the label is problematic, perhaps it’s time to de-mystify, clarify and de-problematize it. We understand our colleagues that are scared for their career, or have other strategic reasons, to not speak up, as that is a consequence of the nature of our field. But yet, we encourage more allies to speak up and say we are heterodox–to show the strength and diversity of heterodox economics. The more scholars identity with the term, the more status and acknowledgement heterodox scholarship will get. If we stand together we can show the world what Economics is missing. Come join us outside of the heterodox closet

We are grateful to Cleo Chassonnery-Zaïgouche, Danielle Guizzo and Matías Vernengo for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven is a Lecturer in International Development at the University of York. @ingridharvold

Carolina Alves is a Joan Robinson Research Fellow in Heterodox Economics at University of Cambridge, the U.K. @cacrisalves.

Sources

Ayres, Clarence Edwin. 1936. ‘Fifty Years’ Development in Ideas of Human Nature and Motivation,’ American Economic Review 26(1): 224-236.

Barbosa-Filho, Nelson and Taylor, Lance. 2006. ‘Distributive and Demand Cycles in the U.S. Economy–A Structuralist Goodwin Model’, Metroeconomica, 57 (3): 389-411

Bhaduri, Amit and Stephen A. Marglin. 1990. ‘Unemployment and the real wage: the economic basis for contesting political ideologies’. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 14(4): 375-93.

Caverzasi, Eugenio and Godin, Antonie. 2015. ‘Financialisation and the sub-prime crisis: a stock-flow consistent model’, European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention, 12 (1): 73-92.

Cartwright, Nancy. 1999. The Vanity of Rigour in Economics: Theoretical Models and Galilean Experiments.

Cedrini, Mario and Magda Fontana. 2018. ‘Just another niche in the wall? How specialization is changing the face of mainstream economics,’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 42(2): 427–451.

Colander, David. 2009. Moving Beyond the Rhetoric of Pluralism: Suggestions for an ‘Inside the Mainstream’ Heterodoxy, in R. Garnett, E.K. Olsen and M. Starr (eds.), Economic Pluralism. London and New York: Routledge.

Colander, David., Richard Holt and Barkley Rosser. 2010. ‘The changing face of mainstream economics,’ Review of Political Economy 16(4): 485-499.

Coyle, Diane. 2007. The Soulful Science: What Economists Really Do and Why it Matters. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Coyle, Diane. 2013. ‘The State of Economics and Education of Economists,’ World Economics Association Curriculum Conference, The Economics Curriculum–A Radical Reformulation.

Dafermos, Yannis & Nikolaidi, Maria & Galanis, Giorgos. 2017. ’A stock-flow-fund ecological macroeconomic model’, Ecological Economics, 131(C): 191-207.

Dequech, David. 2018. ‘Applying the Concept of Mainstream Economics outside the United States: General Remarks and the Case of Brazil as an Example of the Institutionalization of Pluralism,’ Journal of Economic Issues 52(4): 904-924.

D’Ippoliti, C. 2018. “‘Many-Citedness’: Citations Measure More Than Just Scientific Impact”. Working Paper, No. 57.

Dos Santos, Claudio 2006. ‘Keynesian theorising during hard times: stock-flow consistent models as an unexplored ‘frontier’ of Keynesian macroeconomics’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 30 (4): pp. 541-565.

Dow, Sheila. 1990 . Beyond Dualism. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 14(2): 143–157.

Dow, Sheila. 1997. ‘Mainstream economic methodology,’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 21(1): 73–93.

Dow, Sheila. 2008. ‘Pluralism and Heterodoxy: Introduction to the Special Issue,’ The Journal of Philosophical Economics I:2, 73-96.

Dutt, Amitava Krishna. 1984. ‘Stagnation, income distribution and monopoly power’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 8 (1), pp. 25–40.

Epstein, Joshua M and Axtell, Robert L. 1996. Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science From the Bottom Up. MIT/Brookings Institution.

Foley, Duncan K. 2003. Unholy Trinity: Labor, Capital and Land in the New Economy. London: Routledge.

García-Molina, Mario and Ruíz-Tavera, Jeanne Kelly. 2009. ‘Thirlwall’s Law and the two-gap model: toward an unified ‘dynamic gap’ model’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 32 (2): 269-290.

Goodwin, Richard, 1967. ‘A growth cycle’, in: Carl Feinstein, editor, Socialism, capitalism, and economic growth: essays presented to Maurice Dobb. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hands, D. W. 2011. Orthodox and Heterodox Economics in Recent Economic Methodology. Available at SSRN.

Higgins, W. and G. Dow. 2013. Politics Against Pessimism. Berne: Peter Lang.

Jo, Ta-Hee and Zdravka Todorova. 2015. ‘Introduction: Frederic S. Lee’s contributions to heterodox economics,’ in Jo, Ta-Hee and Zdravka Todorova (eds). Advancing the Frontiers of Heterodox Economics Essays in Honor of Frederic S. Lee.

Julius, A. J. 2009. The wage-wage-…-wage-profit relation in a multisector bargaining economy, Metroeconomica, 60: 3, 2009

King, J.E. 2013., A Case for Pluralism in Economics, Economics and Labour Relations Review 24, pp. 17-31.

Lavoie, Marc. 2009. Introduction to post-Keynesian Economics. Palgrave Macmillan: London.

Lavoie, Marc. 2014. Post-Keynesian Economics – New Foundations.

Lavoie, Marc and Godley, Wynne (2006) ‘Features of a realistic banking system within a post-Keynesian stock-flow consistent model, in Mark Setterfield (ed.), Complexity, Endogenous Money and Macroeconomic Theory: Essays in Honour of Basil J. Moore, Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, pp. 251-268.

Lawson, Tony 2015. ‘A Conception of Social Ontology’, in Stephen Pratten (ed.) Social Ontology and Modern Economics, London and New York: Routledge.

Lawson, Tony. 2006. ‘The nature of heterodox economics,’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 30(4): 483-505.

Lawson, Tony 2013. What is this ‘school’ called neoclassical economics?, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 37 (5): 947–983.

Lee, Fred. 2009. A History of Heterodox Economics: Challenging the mainstream in the twentieth century.

Lee, Fred. 2017. Microeconomic Theory: A Heterodox Approach. Routledge: London.

Lee, Fred and Marc Lavoie (eds). 2012. In Defense of Post-Keynesian and Heterodox Economics: Responses to their Critics. Routledge.

Lee, Fred, Xuan Pham and Gyun Gu. 2013. ‘The UK Research Assessment Exercise and the narrowing of UK economics,’ Cambridge Journal of Economics 37(4): 693–717.

Kinsella, Stephen and Khalil, Saed. 2011. ‘Debt-Deflation in a Stock Flow Consistent Macromodel’, in Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, Gennaro Zezza (eds.), Contributions in Stock-Flow Consistent Modeling: Essays in Honor of Wynne Godley, Palgrave MacMillan.

Mariyani-Squire, E and M. Moussa. 2014. ‘Fallibilism, Liberalism and Stilwell’s Advocacy for Pluralism in Economics,’ The Journal of Australian Political Economy (75): 194-210.

Mason, J.W. 2018. ‘A Demystifying Decade for Economics,’ Jacobin, November 2018.

Mearman, Andrew. 2011. Pluralism, Heterodoxy and the Rhetoric of Distinction. Review of Radical Political Economics, 43(4): 552–561.

Mearman, Andrew, Danielle Guizzo and Sebastian Berger. 2017. ‘Is UK economics teaching changing? Evaluating the new subject benchmark statement,’ Review of Social Economy 76(3): 377-396.

Michell, Jo. 2016. On ‘Heterodox Economics’. Critical Finance August 9th 2016.

Pasinetti, Luigi, L. 1962. ‘Rate of Profit and Income Distribution in Relation to the Rate of Economic Growth’, Review of Economic Studies 29 (4): 267-279

Passarella, Marco. 2012. ‘A simplified stock-flow consistent dynamic model of the systemic financial fragility in the ‘New Capitalism’, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83 (3): 570-582.

Tesfatsion, Leigh and Judd, Kenneth L. (eds.). 2006. Handbook of Computational Economics, Volume II: Agent-Based Computational Economics. Elsevier/North-Holland: Amsterdam.

Thornton, Tim. 2015. ‘The changing face of mainstream economics?’ Journal of Australian Political Economy 75 (11)-26.

Turner, Paul. 1999. ‘The Balance of Payments Constraint and the Post 1973 Slowdown of Economic Growth in the G7 Economies’, International Review of Applied Economics, 13 (1): 41-53.

Setterfield, Mark. 2000. ‘Expectations, Endogenous Money, and the Business Cycle: An Exercise in Open Systems Modeling’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 23(1): 77-105.

Skidelsky, Robert. 2018. How Economics Survived the Economic Crisis. Project Syndicate. Jan, 2018.

Skott, Peter. 2008. ‘Growth, instability and cycles: Harrodian and Kaleckian models of accumulation and income distribution’, UMASS Amherst Economics Working Papers 2008-12, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Economics.

Skott, Peter and Ryoo, Soon, 2015. ‘Functional finance and intergenerational distribution in a Keynesian OLG model’, UMASS Amherst Economics Working Papers 2015-13, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Department of Economic.

Steinbaum, Marshall. 2019. ‘Economics After Neoliberalism,’ The Boston Review February 28, 2019.

Stilwell, Frank. 2016. ‘Heterodox economics or political economy?’ World Economics Association Newsletter 6(1): 2-6. (longer version published in Studies in Political Economy, 2012).

Tavani, Daniele. (2012). ‘Wage Bargaining and Induced Technical Change in a Linear Economy: Model and Application to the U.S. (1963-2003)’. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics. 23 (2): 117-126

Vera, Leonardo A. (2006) ‘The Balance of Payments Constrained Growth Model : A North-South Approach’, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 29 (1): 67-92.

Vernengo, Matías . 2011. ‘The meaning of heterodox economics, and why it matters,’ Naked Keynesianism May 18th 2011.

Vernengo, Matías. 2014. ‘Conversation or monologue? on advising heterodox economists,’Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics 32(3): 389-396.

Wrenn, M. 2007. What is Heterodox Economics? Conversations with Historians of Economic Thought. Forum for Social Economics, 36(2): 97–108.

Zamparelli, Luca. 2014. ‘Induced Innovation, Endogenous Technical Change, and Income Distribution in a Labor Constrained Model of Classical Growth’, Metroeconomica, 66(2): 243-262.

Zezza, Gennaro (2004) ‘Some Simple, Consistent Models of the Monetary Circuit’, Levy Economics Institute Working paper no 405.