Recent protests rocked Georgia’s capital Tbilisi against a duo of proposed foreign agents bills, which would have required groups and individuals with significant funding abroad to register as foreign agents. Although similar legislation is law in the United States and under consideration in the European Union, protestors decried the bills as exceptionally anti-democratic, obstructive to Georgian civil society, and even as pro-Russian.

While the Georgian government has withdrawn the bills under international pressure, western-backed groups behind the EU- and Ukraine-flag-studded protests have often emphasized the demonstrations are about a higher cause: Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic future. Opposition and Pro-European Droa Party spokesperson Giga Lemonjala, for example, said amidst the bills’ withdrawal that “[w]e are ready to go on with the protests because it’s…about Georgian European and Euro-Atlantic aspirations…Georgia should be a member of the European Union.”

The Georgian opposition has demanded Parliament’s resignation, calling for early elections. Although the protests have effectively dissipated, Tbilisi’s atmosphere remains uneasy, especially as NATO’s proxy war continues in nearby Ukraine.

From afar, the protests may appear organic; indeed, some likely attended to express legitimate grievances against their government, and many genuinely desire Georgia’s closer alignment with Europe. But the Georgian protests share a striking resemblance with what’s increasingly understood as the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) color revolution “playbook,” where apparently authentic, but actually western-concocted, popular movements drive policy and even regime change. In Georgia’s case, government legislative attempts at increased oversight on foreign influences in civil society were quickly met with mass resistance from western and western-influenced groups in Georgia and internationally, resulting in the foreign agent bills’ disposal.

In Tbilisi’s Protests, Western-Funded Groups Take Center Stage

Despite its frequent utilization, the color revolution tactic remains popular because it marries the intelligence community’s “soft-power” tactics, which largely allow their operations to continue un-scrutinized, with popular movements that may genuinely appear as the peoples’ will. While the operations often pose as the vanguard of “democracy,” or “human rights,” such efforts in fact damage or undermine the political independence of the states they target, barring them from sovereignty and dignity.

And although Georgia’s recent demonstrations have largely concluded sans regime change, they’ve emulated the apparently popular movements that kicked off previous western “color revolutions” including in their widespread western support, promotion, and funding. Despite their brevity, early March’s youth-heavy Georgian protests circulated heavily in mainstream media circles. And prominent western-aligned and funded human rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch both released statements against the Georgian bills, decrying them as anti-free speech and undemocratic.

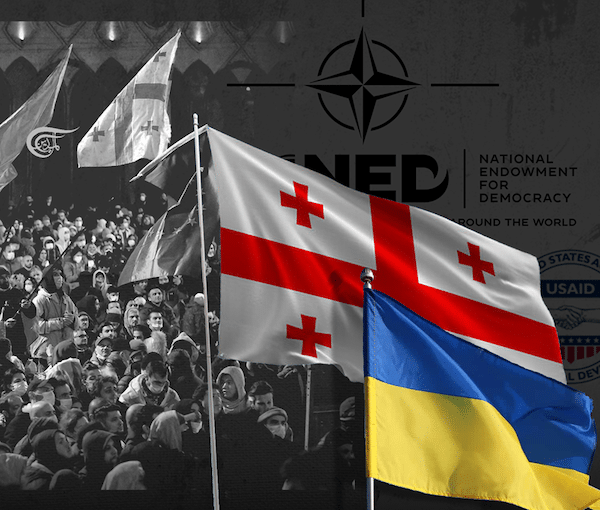

Considering the demonstrations’ widespread western coverage, it’s unsurprising that groups supporting or otherwise promoting prominent Georgian protest sentiments share a common denominator: western, and especially American, funding. Among the most prominent funders is the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a U.S. backed-organization established as a CIA front group, which has financially supported many organizations operating in Georgia. For example, the Shame Movement, which describes itself on Twitter as a “voice of freedom fighters and democracy builders across Georgia,” received over $140,000 from the NED in 2021. The Shame Movement heavily promoted the protests as they struck Tbilisi in March, tweeting a myriad of protest photos and updates.

And Georgia-based media organizations promoting both the protests and a larger pro-European sentiment, such as Eurasianet and iFact, also receive significant western funds, with iFact receiving $50,121 from the NED in 2021. While fellow Georgian outlet Open Caucasus Media, or OC Media, claims to produce “fierce, independent journalism,” the donors’ blurb on their “Who We Are” page reveals significant assistance from western-aligned and foreign government entities, including the NED, George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, and the U.S., Czech and Swiss Embassies in Tbilisi.

Like previous color revolutions’ messaging, these western-backed media organizations repeatedly call for substantial governmental changes and even assistance from abroad. Responding to the protests, for example, OC Media’s editorial board emphasized the need for international intervention, positing that “[t]he Russian-style foreign agent law…could spell the beginning of the end for Georgia’s experiment with democracy. Only decisive action, in Georgia and from abroad, can prevent Georgia’s descent into authoritarianism.”

Helping mount pressure, further, employees at this myriad of western-backed institutions and media groups, such as members of the U.S.-backed Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab and OC Media, were also especially vocal Georgian protest supporters on Twitter.

U.S. officials also condemned Georgia’s foreign agent bills, emphasizing the protests in Georgia must go on undeterred. Tweets by United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Administrator Samantha Power, where Power proclaimed the new legislation “gravely threaten[ed] Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic future,” circulated as protests grew. And State Department Spokesperson Ned Price, who’s also suggested Georgia’s future was “Euro-Atlantic,” even hinted sanctions were possible if protests in Georgia were repressed.

How Georgia’s Recent Protests Mirror Previous Color Revolutions

The Georgian protests’ clear western influence is not unique. Rather, today’s Georgian protests share an uncanny resemblance with the start of other U.S.-backed color revolutions, such as Kiev’s 2014 Euromaidan, a western-backed uprising which swapped a more neutral President Viktor Yanukovich for U.S.-favored President Petro Poroshenko, and Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution, which also saw regime change.

While the mainstream media portrayed Ukraine’s Euromaidan as a popular uprising for political realignment towards Europe, evidence suggests Washington jumpstarted both the protests and Ukraine’s subsequent regime change through soft-power projects and mass funding efforts. The NED funded a whopping 65 projects in Ukraine at the time; the late journalist Robert Parry described this project cluster as a “shadow structure” that could influence Ukraine’s policy choices. According to ex-US Agent Scott Rickard, moreover, U.S. foreign aid agencies gave about 5 billion USD to various groups at Euromaidan’s forefront.

Although the Georgian protests have not led to regime change, their impact and widespread media coverage can be at least partially attributed to the multitude of civil society and media groups operating in Georgia, which, like Ukraine’s dozens of NED-backed organizations in 2014, are flush with western cash.

And Georgia’s own 2003 Rose Revolution, which prompted the resignation of Eduard Shevardnadze and installed Western-favored Mikheil Saakashvili into Georgia’s presidency, elucidates foreign-propped NGOs’ long-term role in Georgian civil society and political affairs. In fact, western-backed NGOs’ influence on the Rose Revolution’s course of events is widely recognized in the mainstream: former Georgian Foreign Minister and current President Salomé Zourabichvili even wrote in French Geopolitical Magazine Herodote in 2008 that NGOs’ work to “carry” the Rose Revolution uprisings translated to their greater influence in government:

These institutions were the cradle of democratization, notably the Soros Foundation … all the NGOs which gravitate around the Soros Foundation undeniably carried the revolution. However, one cannot end one’s analysis with the revolution and one clearly sees that, afterwards, the Soros Foundation and the NGOs were integrated into power.

Just as western-backed media organizations played major roles in the recent Georgia protests, media groups including Ukraine’s Hromadske (funded by groups including the NED, USAID, and the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine) and Georgia’s Rustavi 2 (borne in the 1990s from western assistance from groups like USAID-funded Internews, Rustavi 2 later received USAID funds and support[1]), proved critical to the Euromaidan and Rose Revolution’s respective successes because they helped create the perception of widespread support for the uprisings and their respective goals. The prominent role western-backed media groups played in the recent Georgia protests suggests the elite have taken Euromaidan- and Rose Revolution era media successes into account.

In the wake of Georgia’s western-backed protests, finally, Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili’s comments that Georgia’s denied repeated requests from Kiev to open a “second front” in the ongoing NATO proxy conflict are remarkable. Noting the development, which suggests significant war-time pressure on Tbilisi, Kit Klarenberg writes in MintPress News that “[o]ne can only speculate whether [Georgia’s incumbent party] Georgian Dream specifically pursued the foreign agent law in order to prevent the NED-sponsored installation of a government more amenable to opening a “second front” and imposing sanctions on Russia.”

Conclusion

While the protests have dissipated since the foreign agents bills’ disposal, their forceful appearance in Georgia elucidates how U.S.- and western-backed groups can quickly muster influence over ongoing events when sovereign states feign resistance to their efforts. In this case, Georgia’s attempts to maintain sovereignty through additional controls over foreign-backed groups failed due to widespread, western-facilitated outrage that took similar form to previous “color revolutions’” respective beginnings.

And even as demonstrations dissolve, some western politicians’ statements only take the reins of Georgia’s future westward while further stirring hostilities with Russia. German Green Party MEP Viola von Cramon, for example, recently declared that “The Georgian Government is determined to sabotage Georgia’s European path. Thankfully people of Georgia are not taking it. There is no way back to the Russian swamp.”

But not all are happy with the recent pro-European protests. Albeit receiving little news coverage, counter-protestors in Tbilisi burned the EU flag in front of Georgia’s parliament building in mid-March, and anti-western demonstrations stormed the Georgian capital in response to the recent debacle.

All eyes should be on Georgia in the weeks to come for further developments.

Anable, David. “The Role of Georgia’s Media and Western Aid in the Rose Revolution.” The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 11, no.3 (2006): 7-43.