Three years ago, I wrote an article for Monthly Review entitled “The U.S. Economy in 1999: Goldilocks Meets a Big Bad Bear?” (March 1999).1 My answer to that question was yes, Goldilocks would soon meet a big bad bear, that is, the U.S. economy would fall into recession within a year or so. The recession came a little later than I thought, but, as is well known, the U.S. economy did indeed fall into recession in early 2001.

Now the question on most people’s minds is: how bad will the current recession be? How bad will the bear be that Goldilocks has encountered? The vast majority of economists think that the current recession will be brief and mild, a “garden variety recession,” without special problems, and will probably be over by the time this article is published (one economist even recently called it a “recessionette” a recent Business Week feature article was entitled “What Recession?”). Economists generally emphasize the following factors as reasons for this optimistic forecast: Business inventories of unsold goods declined significantly in 2001, so that excess inventories have largely been eliminated; if sales continue more or less at the same pace, then production will soon have to increase just to keep inventories at their current desired levels. Initial claims for unemployment insurance have also declined in recent weeks, which suggests that the worst of the layoffs are behind us. Consumer spending has remained strong in spite of the recession. Consumer confidence has rebounded in recent weeks from its lows last fall, which suggests that consumer spending will remain strong in the coming months. Housing sales and construction have also remained strong, in large part fueled by lower mortgage rates. And oil prices have declined, putting an additional $60-80 billion in the pocketbooks of consumers for other purchases.

In addition to these internal economic factors, economists also emphasize expansionary government economic policies that are already in place and that should also help to promote a recovery soon from the current recession. This is especially true of monetary policy. The Federal Reserve Board has lowered its target “federal funds rate” eleven times this year, from 6.5 percent to 1.75 percent, which is the lowest it has been since 1958. In addition, fiscal policy is mildly expansionary, even though Congress was not able to agree on additional stimulus. The tax rebates from last summer have increased household’s after-tax income by $40 billion, and the extra spending for the war effort and to pay for the damages of New York will inject another $40 billion of spending into the economy this year.2

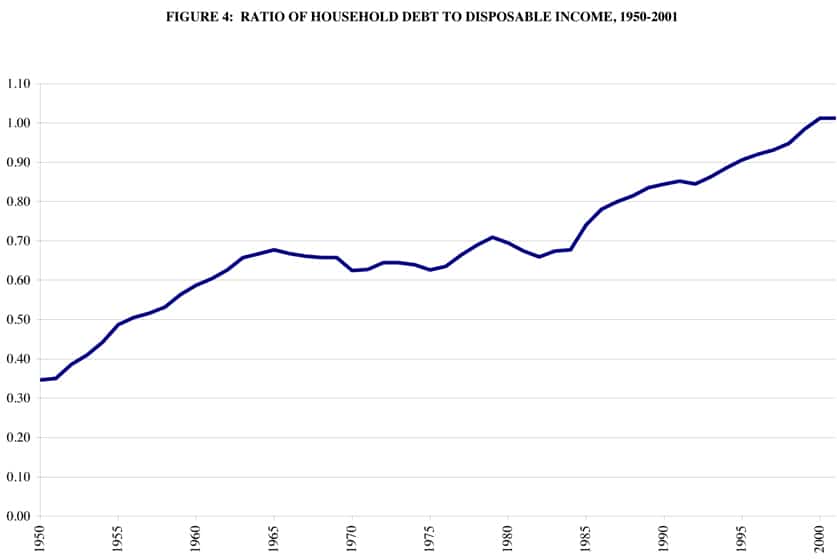

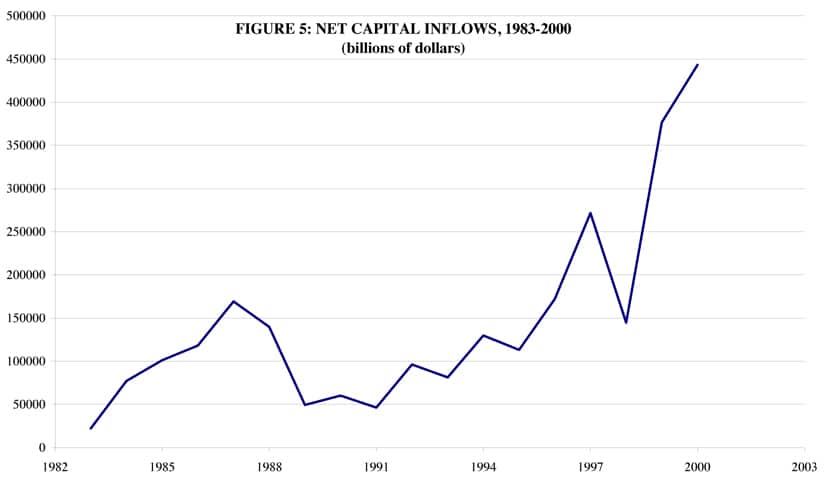

However, I think there are reasons for concern that this recession might turn out to be worse that this consensus forecast (and perhaps much worse). The main reasons for concern are: (1) profits have declined sharply in recent years, and are likely to continue to decline in 2002, which will continue to have negative effects on business investment spending; (2) business indebtedness is at an all-time record high, which will further restrain investment spending in the year ahead, and also increases the risks of defaults (on corporate bonds and bank loans) and more business bankruptcies; (3) household indebtedness is also at a record high level, which will similarly restrain consumer spending, and also increases the risks of defaults (on home mortgages, auto loans, and credit-card debt) and more personal bankruptcies; and (4) the net inflow foreign capital in to the United States has exploded since the early 1980s, a total of over $2.5 trillion over this period, which makes the U.S. economy vulnerable to an outflow of this foreign capital.

This paper will examine each of these causes for concern in greater detail.

1. Falling Profits and Declining Investment

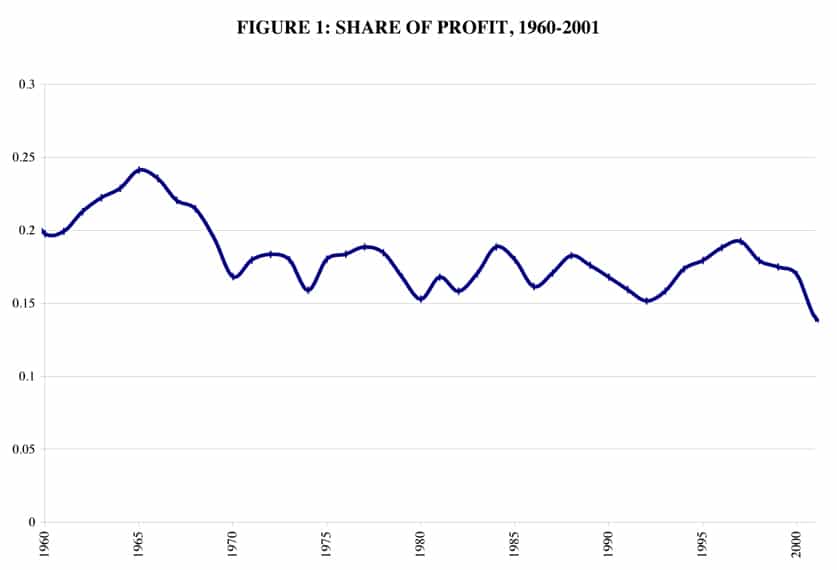

The current recession was caused mainly by a sharp decline in business investment spending (a decline of about 10 percent so far), which in turn was caused mainly by an even bigger decline in the share of profit in total income. The share of profit declined approximately 25 percent from 19.2 percent in 1997 to 14.0 percent 2001 (see Figure 1; these estimates are for the Non-Financial Corporate Business sector of the economy, and include interest as a broader measure of the “return to capital”).3 This sharp decline has wiped out the previous significant increase in the share of profit from 1992 to 1997, so that the share of profit in 2001 was even lower than it was in the early 1990s; indeed it was the lowest of the entire postwar period. In the late 1960s and 1970s, the share of profit declined approximately 35 percent and has never recovered (see Figure 1; see Moseley 1992 and 1997 for analyses of the decline in the rate and the share of profit in the postwar U.S. economy).

These government estimates of a declining share of profit present a very different picture from the glowing reports of record profits by corporations in recent years, which have consistently claimed double-digit increases in their profits! The explanation of this contradiction is a set of new accounting tricks that corporations have adopted in the 1990s, in order to make their profits look much better on their books than they actually are in reality. These new accounting tricks include: stock options for top managers are not counted as a cost, and hence are implicitly counted as profit; other expenses (such as the write-off of losses) are claimed to be “non-recurring expenses”, and are added back to arrive at what is called “operating profit”, as opposed to actual “reported profit” sometimes all pretense of generally accepted accounting principles is given up, and costs are defined however an individual company chooses, in order to arrive at what is called “pro-forma profit” (this “just say anything” method of accounting was especially prevalent during the dot.com boom, but persists today in many companies). Enron carried this new art of creative accounting to new and fraudulent levels. For example, Enron claimed $600 million of revenue from a joint venture with Blockbuster, but Blockbuster claims that there was no revenue at all (“we were astonished to see the numbers”). One wonders how many more Enrons will be discovered in the months ahead. Tyco and Qwest appear to be the next big suspects.

These deceptive claims of double-digit profit increases of course fueled the stock market boom of the late 1990s, which in turn resulted in a significant increase in consumer spending (the “wealth effect”) and a faster overall rate of growth in the economy. Once the full scope of these illusionary profits are realized, the stock market will probably fall even further than it has over the two years, with consequent negative effects on consumer spending and the economy as a whole. The Enron scare has hit the stock market in recent weeks (early February), and threatens to send stock prices lower, as investors no longer trust the profit reports of corporations. If that happens, then the “wealth effect” will go in reverse, and will have a negative effect on consumer spending and the economy as a whole.

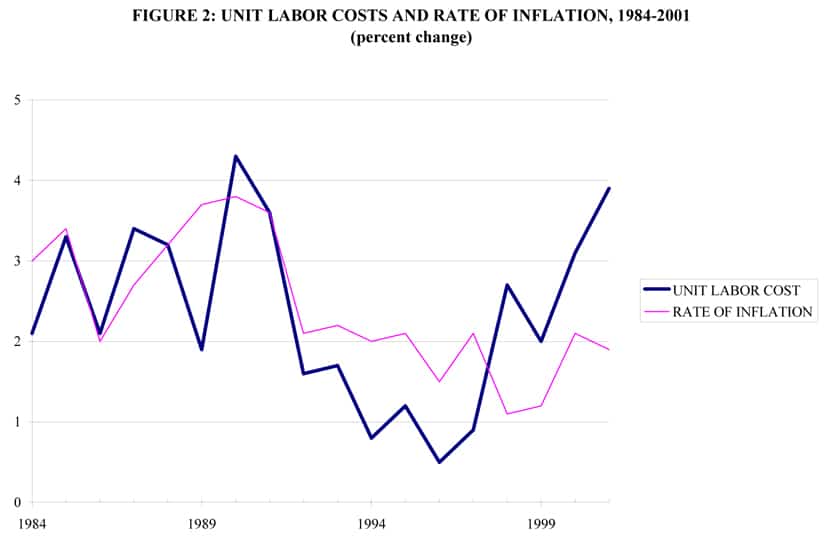

The profit share of total income depends on the relative rates of increase of prices and costs, especially labor costs. In recent years, the profit share declined because labor costs have increased faster than prices (see Figure 2). It seems likely that in the year ahead, labor costs will continue to increase faster than prices, because the rate of inflation will probably be very low, certainly less than 2 percent and perhaps even less than 1 percent. There is even a serious threat of deflation in the U.S. economy for the first time since the Great Depression. In the fourth quarter of 2001, prices in the nonfarm business sector declined at an annual rate of 1.8 percent. Such a low rate of inflation is good for consumers, but is very bad for profits (a recent New York Times article was entitled “Bargains Cheer Buyers, but May Hurt the Economy” i.e., may hurt profits). Labor costs will probably increase at a slower rate as a result of higher unemployment, but will probably still be higher than the very low (or nonexistent) rate of inflation. Therefore, the profit share will probably continue to decline in 2002; at the very least, the profit share is not likely to increase. This low share of profit will continue to have a negative effect on business investment.

The current high level of stock prices are based on much more optimistic expectations of significantly higher profits in 2002 (“double digit increases”). If these higher profits do not materialize, which seems likely (especially since fancy accounting tricks will now be more carefully scrutinized), a negative reaction could send stock prices sharply lower.

2. Record High Business Debt

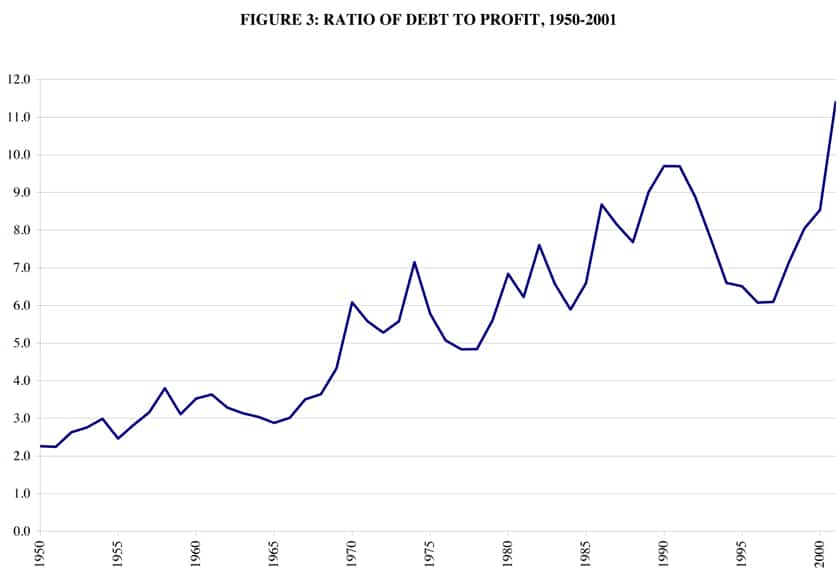

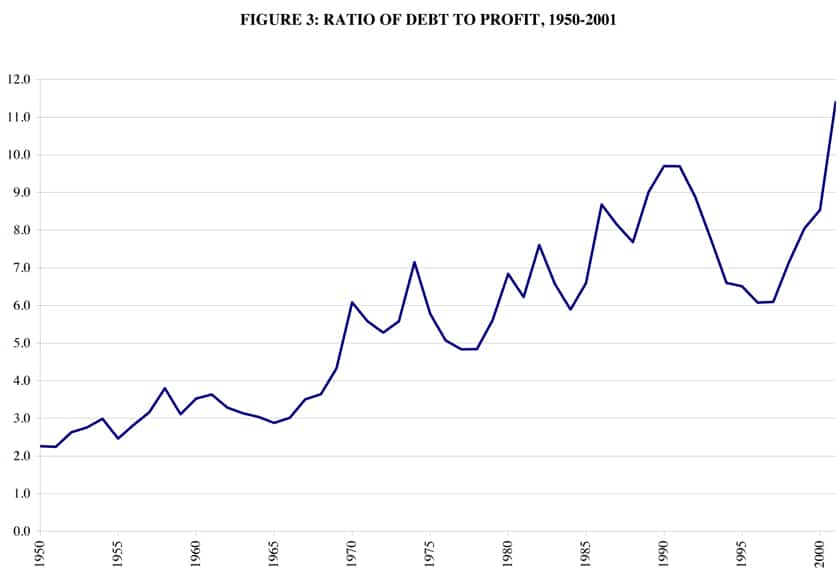

Another important factor, besides low profits, which will also have a negative effect on investment spending in the coming year (and beyond), is the very high level of debt that businesses are currently carrying. As a measure of this indebtedness, Figure 3 presents the ratio of debt to profit for the nonfinancial corporate business sector of the economy, from 1950 to 2001. As we can see, this ratio increased steadily (with some cyclical fluctuations) from around 3.0 in the 1950s to the peak of almost 10.0 in the recession of 1990-1991. Then this ratio fell from 1991 to 1997 to around 6.0, as firms apparently tried to reduce their debt burdens. However, since 1997, this ratio has recovered all the lost ground and more, due to both double-digit rates of increase of debt (that fueled the investment boom of these years) and rapidly falling profits, as discussed above. This graph provides a stark indicator of the increasing financial vulnerability of U.S. corporations in recent years.

Furthermore, the spectacular Enron bankruptcy brings to light the importance of debts that are kept “off the books” of non-financial corporations by fancy (and in Enron’s case fraudulent) accounting tricks. The disclosure of Enron’s billions of dollars of “off the books” debt started its quick collapse into bankruptcy. The question naturally arises: how much debt is “off the books” in the nonfinancial corporate business sector as a whole? We do not know the answer at the present time, but my guess is that the amount of “off the books” debt is very significant. Therefore, Figure 3 understates the real debt burden of nonfinancial corporations. The dip in the early 1990s may have been due in large part to the increasing transfer of debt from the books of nonfinancial corporations to “special purpose vehicles”. And then the use of these “vehicles” accelerated in the late 1990s.

Astonishingly, about 50 percent of the money borrowed by corporations in the late 1990s was used, not to build new plants and equipment, but rather to repurchase the companies’ own stock! Such “repurchases” did nothing to the companies’ ability to produce profit, which could be used to service the debt in the future. Instead, such “repurchases” only caused a temporary boost in the companies’ stock prices, which increased the value of the stocks owned by the top executives of these companies. This begins to look more and more like a house of cards, created by and for the short-run greed of corporate executives.

This heavy debt burden of corporations will have a negative effect on the U.S. economy in the coming years. At the very least, even if the economy does recover from the recession soon, this heavy debt burden will be a restraint on business investment in the years ahead, as firms try to reduce their debt burdens (or at least not to increase them) by reducing their investment spending. On the other hand, a deeper recession would cause more and more companies to default on their debt obligations and more to fall into bankruptcy. Already, the default rate on “high risk” corporate bonds has increased sharply, from 6.5 percent in 2000 to 11 percent in 2001, equaling the record high for the post World War II period in 1991 (with the defaults so far concentrated in the telecommunications industry). Furthermore, the credit rating of corporate bonds that have not yet defaulted has continued to deteriorate. The ratio of “downgrades” to “upgrades” of credit ratings has increased, from 2.3 in 2000 to 3.0 in 2001 (a “downgrade” of credit quality indicates a higher probability of default). A deeper and longer recession would push many of these financially vulnerable companies into default in the year ahead.

In the worst case, increasing defaults could lead to a “credit crunch”, in which banks and investors sharply reduce the amount of money that they are willing to lend, as in the case of the telecommunications industry in the last two years. In recent weeks, the bankruptcies of Enron, K-Mart, and Global Crossing have already spooked investors and led to tighter credit standards and higher “risk premiums”. A more general credit crunch would in turn make the recession even worse, because many businesses would be unable to obtain credit for investment or even for survival.

3. Record High Household Debt

Not only are U.S. corporations indebted to an unprecedented degree; so are U.S. households. Figure 3 presents a common measure of household indebtedness—the ratio of total household debt (both mortgage and consumer debt) to household disposable income (i.e., after-tax income) from 1950 to 2001. We can see that this ratio increased steadily until the mid-1960s (from around 0.2 to around 0.6), then leveled off until the mid-1980s, and then resumed its steady rise until the present, so that this ratio today is greater than 1.0 for the first time in U.S. history.

The rapid increase of household debt has made possible the extraordinary “spending spree” of U.S. households in recent years. From 1995 to the present, consumer spending has increased faster than disposable income every year except one (1998), and the “saving rate” (the ratio of household saving to household disposable income) has declined from 8 percent to 1 percent.

Unlike previous recessions, this strong consumer spending has continued even during the recession so far, and has been the main reason why the recession so far has been relatively mild. In the first three quarters of 2001, consumer spending slowed down somewhat, and was expected to finally turn negative in the fourth quarter, which would have contributed to a deeper recession. However, automobile companies offered “zero interest” financing and mortgages fell to the lowest level in thirty years, and households responded by reaccelerating their rate of borrowing and spending. Instead of declining, consumer spending increased 5.4 percent in the fourth quarter (annual rate). Because of this reaccelerating of consumer spending, the overall output of the economy increased slightly (0.2 percent) in the fourth quarter (after declining 1.3 percent in the third quarter), which has led many economists to conclude that the recession is already over.

However, this reaccelerating of consumer spending in the fourth quarter was financed to a large extent by further increases in household debt. Both consumer debt and mortgage debt increased over 10 percent in the fourth quarter (at annual rates). Although this surge of household debt made possible the spurt of consumer spending in the fourth quarter, it also left households more financially vulnerable to an economic downturn than ever before.

Similar to the debt burden of corporations, the heavy debt burden of households will also probably have a negative effect on the U.S. economy in the years ahead. At the very least, even if the economy does recover from the recession soon, the heavy debt burden of households will probably have a restraining influence on consumer spending. Since there has been no retrenchment of borrowing, as there is in most recessions, there will also be no “bounce-back” effect of increased borrowing to accelerate consumer spending, as in most recoveries.

On the other hand, if the recovery does not come soon, and especially if layoffs continue, then many households will face increasing difficulties in meeting their very high debt obligations. If that happens, then these financially strained households will have to sharply curtail their spending, in order to avoid defaults and bankruptcy, which in turn would make the recession worse. Already, delinquency rates and default rates on mortgages and automobile loans and credit-card debt have increased in 2001.

In the worst case, growing defaults by households, could lead to a “credit crunch” for households, similar to that for corporations, in which banks and other creditors would tighten lending standards and reduce the availability of credit to households. Such a household credit crunch would further reduce consumer spending, and thus further worsen the recession.

4. Record Inflow of Foreign Capital

The previous two sections have discussed the unprecedented indebtedness of U.S. corporations and households, and the dangers this indebtedness poses for the U.S. economy. A related danger is that the U.S. economy has also become increasingly dependent on foreign capital over the last two decades. From the early 1980s (when the United States became a “debtor nation” for the first time since before World War I) to 1994, the average annual net inflow of foreign capital was just under $100 billion, for a total of over $1 trillion (see Figure 4). This increasing dependence on foreign capital by the richest nation in the world is unprecedented in world history, and is sharp contrast both to the U.S. economy during the long post World War II boom and also to the UK economy in the nineteenth century, in which these leading nations were net exporters of capital, not net importers; i.e., were net creditors to the rest of the world, rather than net borrowers.

However, what is even more striking is the sharp increase in the inflow of foreign capital from 1995 to 2000, which adds up to an additional $1.5 trillion in these years alone. This amount was equal to approximately 20 percent of gross private investment in the United States during these years. This is a tremendous infusion of foreign capital, even by colossal U.S. standards. Much has been said in recent years about the foreign debt problem of developing countries around the world. The current deep economic and social crisis in Argentina is due in large part to a foreign debt of about $140 billion. In recent years, the United States has borrowed more than $140 billion or more every year! The U.S. foreign debt is now greater than the total foreign debt of all the developing countries of the world combined!

This huge inflow of foreign capital contributed significantly to the “boom” in the U.S. economy in the late 1990s, in a number of ways: by reducing interest rates, which in turn increased investment spending and also lowered the debt burdens of U.S. corporations and households; by keeping the dollar strong in spite of record U.S. balance of trade deficits; by increasing stock prices which stimulated consumer spending; and by increasing government revenue and surpluses as a result of the faster growth. Without this huge inflow of foreign capital, the U.S. economic “boom” of the late 1990s never would have happened. Of course, these beneficial effects for the U.S. economy were counterbalanced by the opposite harmful effects on the countries that suffered an outflow of capital to the United States.

However, this huge inflow of foreign capital also has its disadvantages for the U.S. economy in the longer run. In the first place, interest and dividends will have to be paid on this foreign capital in future years; that is, a part of the income produced in the U.S. economy every year will have to be used to pay interest and dividends to foreign investors, thereby draining income from the U.S. economy. Furthermore, these payments to foreigners will increase the already record U.S. current account deficit, which in turn will require even more inflows of foreign capital in order to avoid a devaluation of the dollar. It could become a vicious circle, in which increasing inflows of capital require increasing future payments, which in turn require increasing inflows of capital. Obviously, this escalating spiral of payments and loss of income cannot go on forever.

This increasing dependence on foreign capital also makes the U.S. economy increasingly vulnerable to an eventual outflow of this foreign capital, or even to a reduction in the rate of inflow. If the rate of inflow slows down, for whatever reason (see Figure 5), then interest rates in the United States are likely to rise, which would have a negative effect on investment spending and on the rate of growth of the U.S. economy. In the worst case of a withdrawal of foreign capital, then these negative effects would be greatly magnified. Such a “capital flight” from the United States would also put downward pressure on the dollar, which could further intensity the capital outflow. In these circumstances, the Federal Reserve Board would probably increase interest rates further in order to stop the outflow of capital. Such higher interest rates might succeed in stopping the capital flight, but it would also be at the expense of the U.S. economy, further depressing investment spending and also increasing the already heavy debt burden of U.S. corporations and households, thereby increasing the likelihood of more defaults and bankruptcies.

If the recession in the United States is indeed over soon, then the rate of inflow of foreign capital in the United States will probably continue more or less at its recent record levels, and pose no immediate problems for the U.S. economy. However, if the U.S. recession turns out to be longer and more severe, including increasing defaults and bankruptcies, then it is more likely that foreign investors will begin to look more urgently for better places to invest their capital. In this case, the net inflow of capital would slow down and inflows could even turn into outflows (i.e., into “capital flight”).

In addition, other nasty surprises, like a further significant decline in the U.S. stock market, could also trigger a capital flight from the United States. Such a decline in the stock market is not far-fetched. By some measures, based either on the government’s estimates of the profits of U.S. corporations (as discussed above) or on the “price-earnings” ratios calculated by Wall Street analysts, U.S. stock prices are still 25-50 percent overvalued. Or the exodus of foreign capital could be triggered by external events, like the Japanese banking crisis, which could force Japanese banks to sell their U.S. assets in order to offset losses at home (Japanese banks own approximately 10 percent of all U.S. Treasury bonds). If such a capital flight were to occur, then the U.S. economy would be in serious trouble.

5. Conclusion: How Bad Will the Recession Be?

We have seen above that the U.S. economy is faced with several potential dangers, that could make the current recession worse that most economists think: low profits, high business debt, high household debt, and high foreign debt. If the U.S. economy does indeed recover from the recession in early 2002, as most economists think, then these dangers should not cause serious problems, at least for now. However, if the economy does not recover in 2002, then there is a strong possibility that one of more of these dangers will make the recession considerably worse. Thus the U.S. economy right now appears to be on something of a slippery slope, with a good chance of a descent into a deeper recession.

There will probably be a small increase of production in the first half of 2002 as an “inventory correction”, i.e., to allow output to catch up with the current rate of sales and to avoid a further reduction of inventories. However, I do not think that such an increase will be sustainable, unless one or more of the other components of aggregate demand also increases in the coming months. Where would the additional increase of demand come from, which could provide the basis for a sustained recovery in 2002 and beyond?

Business investment is not likely to increase in 2002, and is more likely to continue to decline. We have seen above that the profit share is likely to continue to decline in 2002, which will continue to have a negative effect on investment spending. In addition, the high levels of business debt will also cause firms to reduce their investment spending, in order lessen their debt burdens. Furthermore, less than 75 percent of productive capacity is now being utilized, with many plants idle or on short hours. In such a situation, it does not make sense for firms to invest and add to their redundant capacity.

For these reasons, the extraordinary expansionary monetary policy of the last year is not likely to be very successful in stimulating business investment. Expansionary monetary policy is supposed to increase investment spending by reducing interest rates. However, investment spending does not depend only on interest rates. It also depends on the other factors just mentioned, all of which will have negative effects in the year ahead, and which will very likely swamp any positive effect from lower interest rates.

Similarly, U.S. net exports to the rest of the world are not likely to increase in the year ahead. The rest of the world is also in recession, the first synchronized global recession since 1974-1975. The rest of the world is desperately hoping for a recovery of the U.S. economy, which will lift them out of their own recessions, not the other way around. Most economists expected the U.S. balance of trade to decline during the recession, due to reduced demand for imports, which would have given the U.S. economy a boost. However, the balance of trade has worsened even further, as the demand for U.S. exports has declined even more sharply.

Government spending by the federal government will increase some, in order to pay for the “war on terrorism” and the rebuilding of New York. But the amounts are relatively small, a total of perhaps $40 billion (less than one-half of one percent of the U.S. GDP). This small increase at the federal level will be at least partially offset by spending cuts by state and local governments, who are suffering from declining revenues as a result of the recession, and are required by law to have a balanced budget. These budget cuts by state and local governments will reduce social services at a time when they are needed most, as we see happening already in many states.

The only source left for an increase of demand is consumer spending. Therefore, it seems that if the U.S. economy is to recover in 2002, it will require continued increases in consumer spending to provide the boost. How likely is such strong consumer spending in the middle of a recession? Consumer spending depends mainly on household disposable income, which in turn depends mainly on employment and hours worked. If disposable income is to increase in the year ahead, then employment and hours must increase, i.e., firms must hire more workers and run longer shifts.

However, I think that the opposite is more likely to occur in the coming months. As profits continue to decline (as already discussed), firms will be urgently seeking ways to reduce costs in order to increase profits (“cut costs” is the current mantra). One of the main ways to cut costs is to lay off workers, or reduce the hours they are employed, or freeze or cut the wages they are paid. Such measures do indeed reduce costs, but they also reduce household disposable income, which determines consumer spending. Therefore, I think that it is more likely that disposable income and consumer spending will decrease, not increase, in the year ahead, as a result of business attempts to increase profits by reducing costs. Consumer spending will also be negatively affected in the months ahead by the end of “zero percent” financing for automobiles and perhaps also by a further decline in the stock market, as discussed above.4

If this analysis is correct, then the U.S. economy is not very likely to recover from the current recession in 2002, and the dangers of a slide down the slippery slope of defaults and bankruptcies and capital flight and deeper recession will intensify.

It is of course possible that households will continue in their state of denial, and continue to increase their spending in spite of a decline in their disposable income, and make up the difference by going even deeper into debt than they already are. In this case, there might be a slow recovery in 2002, but only as the result of households increasing their already heavy and unprecedented debt burdens. This does not seem to be a very strong basis for a sustainable economic recovery.

The above analysis suggests that, if we want to avoid a potentially severe recession, then the federal government should increase its spending much more than is currently planned, at least another $300 billion (3 percent of GDP). And this increased spending should go directly to those who are suffering the most from the recession: unemployed workers, recipients of state and local government services that have been cut, and low-income homeowners who fall behind on their mortgage payments. Specific policy recommendations would include: increased unemployment benefits and health benefits for unemployed workers, revenue sharing for state governments (to help them make up for the revenue shortfalls caused by the recession), mortgage assistance payments, and rent subsidies.

These policies are much preferable to the Republican proposals of tax cuts for the rich and for the largest corporations, both because these tax cuts would have very little effect on either consumer spending or investment spending in 2002, and thus would not be effective in combating the current recession, and also because it would be scandalous on humanitarian grounds to give all the benefits to the already rich, while many working people are suffering.5

This increased government spending might not solve the long-run problem of insufficient profitability in the U.S. economy, but at least it would help avoid a more serious recession in the short-run, and it would reduce the suffering inflicted by the recession on unemployed and low-income workers.

References

Moseley, Fred 1992. The Falling Rate of Profit in the Postwar United States Economy, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

_____ 1997. “The Rate of Profit and the Future of Capitalism,” Review of Radical Political Economics 29:4: 23-41.

Notes

- ↩ “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” is a children’s fairy tale. In it, Goldilocks finds the bears’ cabin in the woods, and enters it and finds three bowls of soup on the table. She tastes all three bowls and exclaims that the first bowl is “too hot” and the second bowl is “too cold”, but the third bowl is “just right”. The U.S. economy was supposed to be a “Goldilocks economy” because its rate of growth was not too slow and not too fast, but “just right”, resulting in both low unemployment and low inflation at the same time for the first time in decades.

- ↩ Many economists also that the National Bureau of Economic Research (the official arbiter of the beginning and end of recessions in the U.S.) has declared that this recession began last March, and since the average length of recessions in the post World War II U.S. economy has been eleven months, this recession should end in early 2002, according to historical averages.

- ↩ One could also argue that business investment depends more on the rate of profit than the share of profit. The rate of profit also depends on the capital-output ratio in addition to the profit share. In this case, however, the capital-output was essentially constant from 1997 to 2000 (the latest data available), so that the decline in the profit share resulted in a roughly proportional decline in the profit rate. I will focus on the profit share because more up-to-data are available.

- ↩ Roughly two-thirds of the large increase in consumer spending in the fourth quarter was due to increased automobile sales, stimulated by “zero percent financing”. Although this surge of auto sales gave the economy a temporary boost, it also resulted in huge losses for Ford and Chrysler and sharply lower profits for General Motors. It does not seem likely that these companies will continue for long to sell automobiles at a loss. When they end the incentives (as they have already started to do), then spending on automobiles will probably decline significantly, and with it consumer spending as a whole.

- ↩ It has been estimated by the Citizens for Tax Justice (www.ctj.org) that Enron would receive $500 million in tax rebates if the Republican proposal of eliminating the minimum corporate tax retroactively back to 1986 (!) were passed. As it was, Enron’s accounting tricks enabled it to avoid paying taxes in four of the last five years, the same years in which it was reporting “record profits” to Wall St.! The anti-social greed of Enron executives is breath taking. It is beginning to look like that the U.S. economy was indeed in “Goldilocks economy”, but in a different sense, in the sense that Goldilocks ripped off the bears, by eating their soup and sleeping in their beds.