On Monday, August 8th, Japan’s upper house of Parliament unexpectedly joined the French and Dutch electorates to give a sharp slap to neoliberal inevitability. Much to the totally delicious distress of all the usual suspects, from the Financial Times to the Christian Science Monitor, the parliamentarians turned down Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s key piece of neoliberal legislation, the privatization of Japan’s post office. Koizumi immediately carried out his threat to call a snap election, in which his noxious blend of neoliberalism and nationalist jingoism will be put to a test.

Japan’s ruling class has been under severe pressure now for fifteen years. Since the end of the great financial bubble in 1990-1, “Japan Incorporated” has presided over an economy in stagnation. Only in the last several years have there been signs of slight growth, and the banks and financial corporations did not return to profitability for more than a decade.  But capitalism demands accumulation whether the economy as a whole grows or not, and many of the firms with the largest capitalization were able to report profits at historic highs for the fiscal year 2004. This achievement was at the cost of a growing fiscal crisis of the state and the imposition of increasing pressure on the living conditions of working people. The domestic debt of Japan is now by far the largest in proportion to GDP of any advanced industrial nation. And the share of wages in the national income is decreasing, unemployment and part-time employment increasing, and the tax burden shifting from taxes on the rich and corporations to consumption taxes on working people.

But capitalism demands accumulation whether the economy as a whole grows or not, and many of the firms with the largest capitalization were able to report profits at historic highs for the fiscal year 2004. This achievement was at the cost of a growing fiscal crisis of the state and the imposition of increasing pressure on the living conditions of working people. The domestic debt of Japan is now by far the largest in proportion to GDP of any advanced industrial nation. And the share of wages in the national income is decreasing, unemployment and part-time employment increasing, and the tax burden shifting from taxes on the rich and corporations to consumption taxes on working people.

The political management of these policies has been entrusted to the Liberal Democratic Party (“LDP”), in power in Japan continuously (except for a few months in 1993-4) since the U.S. occupation. Their success has relied upon a vigorous use of the state mechanism for patronage and Keynesian counter-cyclical employment creation, the cause of the massive expansion of domestic debt. This client/patronage anti-communist state is a rarity in the world, having outlived its Italian Christian-Democratic cousin now by more than a decade. But even Japan’s relatively favorable position in the world capitalist order does not easily permit its ruling class to accumulate globally while preserving the living standards of its domestic working class. Japan is dependant totally on imports of petroleum products and most essential raw materials, yet has none of the world’s major oil companies. Nor does Japan politically or economically dominate its near neighbors China and South Korea, which have absorbed a large part of its foreign investment but not necessarily on terms of Japan’s choosing.

The central fact for Japan’s ruling class is its subordination to the rulers of the United States. The key corporate centers of accumulation are dependant upon exports on credit of electronic goods and automobiles to the United States, which runs a massive trade deficit with Japan.  The total credits granted to the United States have resulted in some $700 billion of Japanese-held U.S. government debt, by far the largest amount held outside the United States. More than any other nation in the world, the Japanese are financing the current Bush administration policy of tax cuts for the rich, debt binge, and global warfare. When required by their U.S. colleagues, the Japanese ruling class has “voluntarily” limited exports of automobiles to the United States, contributed massive funds to offset the costs of the first U.S. war against Iraq (the “Gulf War”), and, in violation of the U.S. imposed post-war constitution of Japan, sent military units to assist in occupying Iraq after the U.S. invasion.

The total credits granted to the United States have resulted in some $700 billion of Japanese-held U.S. government debt, by far the largest amount held outside the United States. More than any other nation in the world, the Japanese are financing the current Bush administration policy of tax cuts for the rich, debt binge, and global warfare. When required by their U.S. colleagues, the Japanese ruling class has “voluntarily” limited exports of automobiles to the United States, contributed massive funds to offset the costs of the first U.S. war against Iraq (the “Gulf War”), and, in violation of the U.S. imposed post-war constitution of Japan, sent military units to assist in occupying Iraq after the U.S. invasion.

Yet the Japanese ruling class has its divisions, and they can be said to represent the degree of (always muffled and disguised) resistance to U.S. dictates. A fundamental contradiction faced by the Liberal Democrats is that on the one hand Keynesian domestic policies are essential to the continuation of their accustomed pattern of political rule, but on the other the United States has been persistent over the last decades in demanding that Japan adopt the “modern” neoliberal policies that would open key sectors of its economy to penetration and legalized looting (along the lines, for instance, of what happened to the pension funds of United Airlines) by the leading U.S. financial corporations.

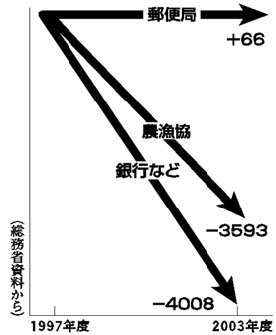

At the heart of this U.S. project is the privatization of the Japanese postal system. The Japanese post office is also a banking and insurance facility, and is present in every nook and cranny of the nation. It provides cash machines operated by credit cards (called in the United States “ATMs”) in even the most remote locations, provides reliable low cost insurance products, and absolutely safe (but virtually non-interest paying) savings deposits in addition to the usual postal services. The post office has over $3 trillion worth of savings under its management, over 24,700 offices, and nearly 300,000 employees. Postal savings funds are in turn invested in extremely low interest domestic debt instruments, financing the vast construction projects on which the Liberal Democratic Party’s patronage system depends. In fact, the post office itself forms no small part of that patronage system. In short, it is a central pillar of the Keynesian client-patron regime, and has been slated for destruction now for many years.

At the heart of this U.S. project is the privatization of the Japanese postal system. The Japanese post office is also a banking and insurance facility, and is present in every nook and cranny of the nation. It provides cash machines operated by credit cards (called in the United States “ATMs”) in even the most remote locations, provides reliable low cost insurance products, and absolutely safe (but virtually non-interest paying) savings deposits in addition to the usual postal services. The post office has over $3 trillion worth of savings under its management, over 24,700 offices, and nearly 300,000 employees. Postal savings funds are in turn invested in extremely low interest domestic debt instruments, financing the vast construction projects on which the Liberal Democratic Party’s patronage system depends. In fact, the post office itself forms no small part of that patronage system. In short, it is a central pillar of the Keynesian client-patron regime, and has been slated for destruction now for many years.

The key giant Japanese corporations believe that they no longer need the LDP regime as protection from the threat of class struggle. Instead it has become an obstacle to a regime of intensified internal accumulation at the expense of Japanese working people along the lines of the U.S. model. A sign of this anachronism is Japan’s continuing relative income equality; the share of national income of the bottom fifth of the population is the highest in the world, twice that of the United States or China. These corporations would readily share with U.S. finance the gravy sure to flow from the multiple securities issues and speculative booms and busts as the postal system is torn apart and the savings of the Japanese people consumed. But more is at issue — the end to the last anti-communist corrupt Keynesian welfare model still left in the world.

The bloc of the largest Japanese corporations and the United States controls the chief positions in the state through Prime Minister Koizumi and Heizo Takenaka, his Minister of State for the Privatization of the Postal Service.  The neoliberal project has been pitched to the public as “reform” by the media techniques invented in the U.S. and U.K. during the Reagan/Thatcher years and since greatly improved. Koizumi has been sold as a movie star politician of the type of Clinton (or Reagan himself). In 1992 he took his first ministerial post, as Posts and Telecommunications Minister, and was the first to raise postal privatization as an issue. On becoming in 2001 President of the LDP, a position that has carried with it the Prime Minister’s job for over fifty years, Koizumi’s first parliamentary address called for privatization of the post office.

The neoliberal project has been pitched to the public as “reform” by the media techniques invented in the U.S. and U.K. during the Reagan/Thatcher years and since greatly improved. Koizumi has been sold as a movie star politician of the type of Clinton (or Reagan himself). In 1992 he took his first ministerial post, as Posts and Telecommunications Minister, and was the first to raise postal privatization as an issue. On becoming in 2001 President of the LDP, a position that has carried with it the Prime Minister’s job for over fifty years, Koizumi’s first parliamentary address called for privatization of the post office.

The U.S. has long understood the crucial position of Japan Postal Service to the self-management of the Japanese economy, and has called for its destruction and privatization from the time of the Clinton administration. With Koizumi in office, the co-ordination has been undisguised. In Japan-U.S. summit talks in September 2004, published reports had President George W. Bush asking Koizumi for a progress report on postal privatization; Koizumi is reported to have said, “We will do our best.” In March 2005 the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (“USTR”) published its annual report on “Foreign Trade Barriers.” The report emphasized the importance the U.S. government attaches to the privatization of postal services in Japan’s “structural reform.” The USTR report is open about U.S. motives: “Structural reform . . . plays an enormous role in increasing market access opportunities for U.S. companies.” Postal Privatization Minister Takenaka has admitted to consulting with U.S. government and insurance industry representatives no less than 18 times in the period in which the postal privatization bills were drawn up.

Koizumi accompanies this servile obedience to U.S. economic dictates with flagrant public displays of Japanese ultra-nationalism, honoring the memory of war criminals and “reforming” textbooks to eliminate any suggestion of guilt for the atrocities of Japan’s imperialist wars in Asia. As a result, Japan’s relations with China and South Korea have sunk to the lowest point in decades.

The extreme neoliberal initiatives demanded by the U.S. have met resistance from national and social minded elements in the powerful permanent governmental bureaucracy, and from sectors of the LDP who see no reason to saw off the branch on which they sit. Privatization Minister Takenaka was frustrated in a previous ministerial stint when an attempt to carry out U.S. demanded “tough measures” (removing deposit protection at a moment when Japan’s banking system was on the ropes) was frustrated by the permanent bureaucrats of Japan’s treasury. And the defeat in the upper house of Koizumi’s crucial postal privatization measure was accomplished by the votes of a significant section of the LDP councilors.

Koizumi repeatedly threatened his LDP opponents with a snap election were they to defeat the postal privatization. The force of the threat was that the LDP would lose such an election, made more certain by Koizumi’s threat to run “official” LDP candidates against parliamentarians who had opposed the bill. His goal is to purge the LDP and create a reliably neoliberal party. He not unreasonably expects the second-rate capitalist politicians of the official opposition party, the permanently out-of-office Japan Democratic Party, to discredit themselves with the inevitable corruption scandals as they first get their snouts in the trough. No doubt he also expects them to reap the popular anger as the Keynesian system disintegrates as a result of the tax-cuts he has carried out, and the impossibility of adding further to the massive debt he has created. On this scenario Koizumi and Takenaka will return triumphant under the tested banner of “There Is No Alternative” to carry out the thoroughgoing destruction of whatever is still fair and decent in Japan.

But such plans are by no means certain of success. Despite a slick and incessant campaign over decades, the neoliberal project has not been approved by the majority of the Japanese. At the very height of Koizumi’s push, the key postal privatization measure was unable to achieve majority support in the opinion polls, and one poll showed a 70 percent opposition to the attempt to force the bill through in the 2005 parliamentary session. Primary credit for this popular resistance goes to the Japan Communist Party (“JCP”), which has been valiant in its opposition not only to postal privatization but also to the neoliberal program itself. And to its enormous credit the JCP has stridently opposed every manifestation of renewed war-mongering nationalism. In addition, the more rational and national minded of Japan’s elites might well see the benefit in finally breaking with the criminal global war and torture policies of the United States, and in a turn toward re-establishing friendly relations with China and both Koreas. Koizumi has, with Tony Blair, been the most useful and loyal of the servants of U.S. imperialism. His humiliating defeat in parliament is reason to be cheerful.

But such plans are by no means certain of success. Despite a slick and incessant campaign over decades, the neoliberal project has not been approved by the majority of the Japanese. At the very height of Koizumi’s push, the key postal privatization measure was unable to achieve majority support in the opinion polls, and one poll showed a 70 percent opposition to the attempt to force the bill through in the 2005 parliamentary session. Primary credit for this popular resistance goes to the Japan Communist Party (“JCP”), which has been valiant in its opposition not only to postal privatization but also to the neoliberal program itself. And to its enormous credit the JCP has stridently opposed every manifestation of renewed war-mongering nationalism. In addition, the more rational and national minded of Japan’s elites might well see the benefit in finally breaking with the criminal global war and torture policies of the United States, and in a turn toward re-establishing friendly relations with China and both Koreas. Koizumi has, with Tony Blair, been the most useful and loyal of the servants of U.S. imperialism. His humiliating defeat in parliament is reason to be cheerful.

John Mage is an Officer and Director of the Monthly Review Foundation.