|

David Houston changed my life. If it weren’t for Dave, I wouldn’t be a political economist, a political activist, and I wouldn’t have a sense of my life as part of a larger historical struggle for economic and social justice. Dave, along with his friend David Bramhall who concentrated on teaching undergraduates, were the sole Marxists in the economics department at the University of Pittsburgh. Dave directed my dissertation in Marxist crisis theory, and protected me from his many traditional colleagues who held a near-religious conviction that market outcomes were desirable. I met Dave in fall 1973, my first year of graduate school, (just as Michael Yates was finishing his graduate work in our department) when I took his course in Radical Political Economics. I enrolled in the course half out of curiosity and because I had mistakenly thought that doing graduate work in economics would enable me to apply my training in mathematics and social science to crafting public policy that would better the lives of working people and poor people. Yeah, I was pretty naïve. Dave was a magnetic presence in class. I can still remember Dave imitating Richard Nixon giving his Checkers speech to illustrate the shallowness of U.S. politics and then recommending that we check out Emile de Antonio‘s film. What I didn’t appreciate until later was that Dave’s humor was not just for show. Dave used humor to disarm students, especially graduate students, and even his neoclassical colleagues in a way that signaled his respect for their beliefs and engaged them in a subversive dialogue that often exposed their privileged position in our society, and how their work perpetuated an exploitative system. It sure worked on me. The Making of A Radical Economist By 1973 Dave was already a Marxist economist, a leader of the Union for Radical Political Economics (URPE), a seasoned antiwar activist (who was spit upon, jailed, and beaten when he led a protest at the Duquesne Club intended to convince Pittsburgh’s business elite to oppose the Viet Nam War); a leader of the Gulf Action Project that sought to nationalizing Gulf Oil, headquartered in Pittsburgh; and was busy organizing protests against the overthrow of Salvador Allende in Chile. All that political activity brought Dave to the attention of the FBI, who couldn’t understand why the University just didn’t fire him. If they could have, the University surely would have fired him (and in today’s political climate they might have done just that). But Dave came to the department in the late 1960s as a tenured professor, recruited to head the department’s concentration in urban and regional economics. Within a year, Dave was one of the youngest full professors in the University. He was fully deserving of that rank. He had amassed a record of wide-ranging and important scholarship that included articles on risk, insurance, and sampling; on metropolitan finance; on economies of scale in the life insurance industry; and on what drives the growth of regional economies. His articles are still referred to as classic studies in literature reviews, in urban and regional economics textbooks, and in recent insurance articles. By the time Dave came to Pitt, he was well along the way of an intellectual and political journey that would make him a Marxist who would dedicate himself to exposing and correcting the injustices of capitalism through his intellectual work and political activism. Dave never went to graduate school in economics. During the 1950s, he earned a PhD in American Civilization from the University of Pennsylvania, where he also taught insurance to undergraduates at the Wharton School. (His father was an insurance broker, and Dave had worked in the insurance industry in New York City.) Disaffected with a curriculum that he thought amounted to little more than elite studies, Dave wrote his dissertation on Elizur Wright, the mid-nineteenth century reformer of the insurance industry. Wright, as commissioner of insurance in Massachusetts, instituted a non-forfeiture policy that put an end to the practice of making people who were unable to pay their life insurance premiums lose all their previous contributions. But Wright, a classmate of John Brown, was also a staunch abolitionist, who devoted much of the early years of his life to campaigning against slavery. Even as he took a job in the business school at UCLA and wrote about insurance, Dave was looking for a way to pursue economic justice issues. He soon befriended Charles Tiebout, the influential and innovative urban and public finance economist, who shared some of those concerns. With Charlie, Dave began writing about regional and urban economic policy. Although their collaboration would become strained as Dave continued to move to the left, their joint work helped Dave move into economics and eventually to Pitt, where he spent the remainder of his career in the economics department. Our Guide During the 1970s and early 1980s, Dave attracted a group of loyal graduate students interested in studying political economy and Marx. Dave had a profound influence on us. Part of the reason was his scholarship. Dave continued to write about regional and urban issues. His articles offered a Marxist interpretation of capital accumulation in Pittsburgh, the decline of the steel industry, and urbanization and capitalism. He also entered into several debates about Marxist theory, including the importance of the distinction between productive and unproductive labor, and developed value-theoretic-based empirical studies. He even penned a popular Marxist guide for community organizing in the midst of the deindustrialization and population flight of the Pittsburgh region. But even more so than his writing, Dave’s personal example inspired us. We use to call him “Dr. Dave” or “fearless leader.” And he was just that. Dave put his career on the line to teach political economy and to speak out against injustice. Dave went from the presumptive next head of the economics department to someone whose work was marginalized by the department leadership. He became an inconvenient presence in a department that had set its sights on national rankings; Dave was alien to that goal and alienated by the means employed to achieve it. Still, even his most ardent critics in the department respected his intellect and his honesty. Of course, that didn’t stop the department from freezing his salary for many years. Dave was never deterred in his fight against orthodoxy. With a fierce determination (or an outright pigheadedness), Dave championed political economy in Pitt’s neoclassical economics department. At the same time Dave helped lead the university-wide effort to unionize faculty and graduate employees. Outside the University, he pursued his socialist politics in the New American Movement and organized the community surrounding the University through People’s Oakland. That he was always a willing spokesperson for the Palestine Solidarity Committee was just another example of how Dave felt compelled to tell his truth. But there was another source of Dave’s profound influence on us. He saw himself as on a never-ending intellectual and political journey. That made Dave an ideal guide for others’ political journey. I remember our seminar on reading Capital as one of the most exciting intellectual experiences of my life. The seminar attracted radical faculty and graduate students from outside of economics, as well as the political economy students. Class was a shared exploration of Marx’s writings that Dave chaired. That was always Dave’s approach to engaging students. A few years after I left Pitt, Dave showed me the end-of-the-semester letter he wrote to the students in his seminar on the labor theory of value. Predictably it closed with these words: “We should look at our studies as a beginning, as a first step on a road that like history has no end.” Nor did Dave ever lose track of where his political journey began. That awareness helped Dave to engage the traditional economists in the department in a dialogue about the value of political economy that, much to our amazement, got some of them to recognize the merit of our work, even our dissertations. I also am sure that explains why Dave dedicated himself to introducing us to the world of radical political economics. I first attended the URPE Summer Conference with Dave in 1975, and we continued to attend the summer conference together for two decades. All that time I never doubted that Dave was on my side. He even sent a letter to the dean of my college promising that I would soon finish my dissertation when there was little reason to believe that was true. (He did scribble “Don’t I lie good” across the top of the copy he sent me.) And once I was finally done with my dissertation, we got on with the more serious business of becoming close friends. In 1988, Dave assumed the job as managing editor of the Review of Radical Political Economics (RRPE), which was badly floundering having fallen a year and half behind schedule. He quickly brought order to the chaos he inherited and got the RRPE back on schedule. Dave was a consummate manager whose leadership combined strength with tact and diplomacy. Dave relished his work, despite being denied the support the department extended to editors of other journals. Dave took early retirement to focus on the journal, when his friend Frank Giarratani became department chair in 1992. That was a happy time in Dave’s work life. Editing the RRPE, planning special issues on topics such as the future of capitalism, filled his days and allowed him to overcome the isolation caused by a lack of graduate students interested in political economy. Also with Frank, Dave wrote a series of papers that assessed the policy options for Pittsburgh and other regions suffering from a chronic population loss. While their articles didn’t change policy-making in the Pittsburgh region, some regions in eastern Germany used the approach outlined by Dave and Frank to cope with their structural adjustment to Germany’s western regions. In his retirement, Dave also began a cultural and political economy study of Miami as a postmodern city with his former New American Movement comrade, literary critic John Beverley (see John Beverley and David Houston, “Notes on Miami,” boundary 2 23.2, Summer 1996). Love and Struggle In June 1996, Dave suffered a severe stroke and massive cerebral hemorrhage that left half his body paralyzed and much of his brain not functioning. He returned home to stay only after spending more than a year in the hospital and rehabilitation center. Through his courage, his physical and personal strength, and the love and support of his wife Jan Carlino, Dave has been able to affect a recovery that has astounded his doctors. Dave remains the same person. He is still engaged politically with the world, he listens regularly to political economy read to him by his nurse, and his impeccable comic timing endures (as shown in the sign that Dave carried at the Washington march against the war in Iraq: “He wanted to be a tree but he was only a Bush.”) In other ways, Dave’s life has changed profoundly. But as he put it in his December 1997 holiday letter to friends and family, “The most significant changes in me are not the physical and mental impairments. Living through the stroke has helped me to develop a rich appreciation for relationships with others. Jan tells me I’ve found my spirit. And while I rejected the idea in a religious sense, I believe she is right. Before the stroke I never realized how important love is and the healing effect it can have.” No so long ago, Dave told me, “Our values are love and struggle.” He is right. And Dave is the very personification of those values — “a beacon for anyone who strives to guide their personal decisions by being honest, open, and true to ideas,” in the words of his friend Frank. That is why my partner Ellen (who was an undergraduate student of Dave’s in a program called the Alternative Curriculum) and I named our son Samuel David. John Miller was a graduate student in the economics department at the University of Pittsburgh from September 1973 to September 1979, when he left to take a job in the economics department at Wheaton College, where he still teaches today. He completed his dissertation in spring 1982. He served on the steering committee of the Union for Radical Political Economics during most of the 1980s, and for the last decades he has been a member of the Dollars & Sense collective and a frequent contributor to the magazine. He is currently editing a reader on the debate among economists about sweatshops and the antisweatshop movement. |

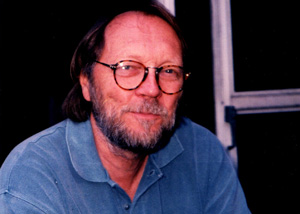

[The following owes a great debt to Gloria Rudolf. She not only rigorously edited two earlier versions of this tribute, but also provided me with valuable information about Pitt’s alternative curriculum.] I began graduate school in economics at the University of Pittsburgh in September 1967. I hated nearly every minute of it. But one professor saved my sanity that first year. His name was David Houston. David was in his mid-thirties and already a full professor; at the time he was the youngest full professor in the history of the department. David impressed me right away. He was different, as his appearance immediately suggested. While my other professors dressed like, well, economists — unstylish and often ill-fitting salt-and-pepper sports coats, white shirts, black shoes, and short hair — David came to class in jeans and a black tee-shirt adorned with a bead necklace. His hair was long, and he wore a headband. And, while most of the professors filled the blackboard with mathematical symbols, elucidating the hypothesis that when every person acted selfishly, society as a whole would be in an optimal state, David skipped much of the mathematics and tried to get us to think. His colleagues never mentioned the war raging in Vietnam and the exploding city streets in the United States, but David had the courage to talk about these and to suggest that economics, conceived as it was originally as political economy, could tell us a lot about why these things were happening. David’s teaching style also set him apart from my other teachers. He David taught macroeconomics, the most important course we took in the second To me David’s class on Vietnam was inspiring. It connected my growing After this class, I made it a point to try to get to know David better. I David took an interest in all aspects of his students’ lives. When I David also introduced me to the Union for Radical Political Economics Once I started teaching, I had to finish my graduate studies and write a PhD David Houston wasn’t just a radical teacher. He believed, and through him, I David was one of a small group of academics who worked to establish and to David was a leader in “People’s Oakland,” a community group in the part of David Houston paid a heavy price for his political activism. He had been Through all of this, David never failed to take a radical stand, whether it In 1988, I moved to Pittsburgh and commuted to work. This gave me a chance David retired in 1993. He planned to continue editing the RRPE, to travel, Michael D. Yates is associate editor of Monthly Review. He attended graduate school at the University of Pittsburgh from 1967 to 1973 (last four years part-time) and received his PhD in economics in 1976. He was for many years professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. He is author of Longer Hours, Fewer Jobs: Employment and Unemployment in the United States (1994), Why Unions Matter (1998), and Naming the System: Inequality and Work in the Global System (2004), all published by Monthly Review Press. |