They can call it a free market, but it’s clearly not free. As for a market, who needs 200 brands of cereal — or 47 prescription drug plans? As my mother-in-law Ruth and I discovered, when it comes to the new drug benefit, more choice is a lot less than it’s cracked up to be.

My first intimate look at the new plan came in late October when Ruth spread a welter of documents on her coffee table. She was atwitter with indignation and anxiety. “I’ve tried to understand it,” she said, “but it’s just too much, it’s crazy!”

Ruth, who turned 90 this year, lives at an independent living facility in Rockville, Maryland. Sure, macular degeneration has fogged her vision, she uses hearing aids, and she’s beset by the aches and pains of longevity; but given her age, she’s in pretty decent shape. Still, this plan was making her sick, and I soon saw why.

The giant document she’d received from Medicare was 98 dense pages long; it required my full attention, not to mention the effort it took for Ruth, who can’t read without a magnifier. As I worked my way through, a few things became apparent: we would need to review her income to see whether she qualified for additional governmental assistance; and we would need to create a list of the drugs she took, along with their approximate monthly costs. Then we’d have to determine which of the available plans covered her medications.

We didn’t even bother to consider the program options that offered managed care plus drugs — a disingenuous attempt to lure seniors from the relatively reliable public Medicare program to private insurance vendors. At 90, Ruth wasn’t about to navigate a completely unfamiliar health delivery system.

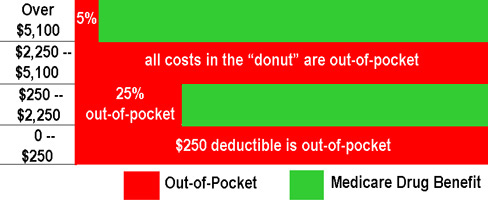

Ruth was ahead of me on the government assistance front. She had already received notification that her combined annual income and assets put her just over the $14,500 threshold for additional relief. Hence, she would be responsible for: the standard $250 deductible required by most of the plans; the monthly premium for whichever plan she chose; plus 25 percent of the cost of her drugs up to $2,250. If her total drug costs exceeded $2,250, she would then fall into the dread “donut” and be responsible for 100 percent of her drug costs between $2,250 and $5,100.

Click on the image for a larger view.

For Ruth, a worst-case scenario would require virtually a third of her entire income for drugs — leaving her just shy of $10,000 for all her other living and medical expenses. Although we supplement her income in a variety of ways, we are not affluent ourselves; and I found myself wondering what would happen to seniors without children to augment puny incomes — or navigate the bewildering jumble of information.

“Why couldn’t we just keep our Maryland plan?” Ruth groaned. The state had provided seniors with a simple, effective option: a $10 monthly fee — plus a co-pay of $10, $20 or $35 — to receive drug benefits of up to $1,100 in a year. Now the state was being forced to abandon its plan for the national one, although it had generously opted to continue helping its seniors with $25 each month to defray drug costs.

As a next step, we made a list of her regular medications: eye drops, generic thyroid, two blood pressure medicines, and two additional drugs not available in generic form. I wrote down the drug names and dosages. How much did they cost her each month? She didn’t know; I’d have to go online and find out.

Now we were ready to stare at the spreadsheet of available plans that a local organization had thoughtfully prepared. The 40-plus options had monthly premiums ranging from $6.44 for a Humana “standard” plan to $68.91 for a Prescription Pathway plan, mysteriously identified as “American Progressive Enhanced #2 Reg 5.” Humana’s two other plans had monthly premiums of $12.58 for “enhanced” and $52.88 for “complete.” Meanwhile Prescription Pathway offered nine different plans, the lowest coming in at $31.59, all with equally obscure names. I looked at the dots in the columns that sketchily summarized the plans’ basic features. A few waived the standard $250 deductible, but otherwise the grid remained mute as to the discrepancy in premiums.

There was a number to call for information, but it was frequently busy; Ruth’s neighbors reported long waits for service, and what’s more, most of them don’t hear so well. The literature also touted the Medicare website as the ideal tool to compare plans and answer questions. But Ruth had given up on trying to master a computer, and the Internet remained a mystery to her.

And so it was that on November 5th, I sat down at my computer to determine the costs of her drugs; it took me about 45 minutes to compare various prices and doses and come up with a reasonable guesstimate of monthly and annual costs. Then I made my first attempt to navigate the Medicare website. It looked promising. I entered Ruth’s personal ID information and pulled up the plans for her region – pretty much matching the spreadsheet she had been given, although a few extra plans had somehow materialized. I found the link for entering a personal itemization of drugs. “Neat,” I thought, as I entered Ruth’s list to check against the plan options. It didn’t work; the website informed me I should try again in a few days.

By the time I logged back in on November 12th, the website was finally working; but it didn’t remember Ruth, and I had to re-enter all the information. By now I was more familiar with the site and quickly able to determine which plans covered the drugs she took, and at what cost.

Then we made yet another unwelcome discovery: The cost of each drug, under each plan, varied according to pharmacy. Ruth prefers NeighborCare, where the staff remembers her name and makes deliveries; but it was also more expensive. For one plan, First Health Premier, the annual estimated cost for her would be $1,895.69 through the pharmacy at Giant, $1,912.23 at CVS, and $2,296.18 at NeighborCare. But Ruth was adamant about keeping NeighborCare; how else would she get her medication if it snowed or if she was hit by flu? This meant that First Health, which had seemed like a possible option based on its premium and drug costs, would actually turn out to be more expensive than some other plans.

I did my best, honest, but after reading all the literature, and hours of computer time, I still felt like something was eluding me. What if Ruth suddenly got another illness? There was no way to tell whether her new drugs would be covered under the plan we chose. Could we lower her costs by substituting one drug for another — and then would that drug be covered? Given that many of these plans had popped up to populate this new private profit enterprise zone, wouldn’t a few of them inevitably go belly-up, or turn out to be frauds? What then? Furthermore, the drugs were listed in each plan as tier one, two, or three; different drugs were in different tiers on different plans — and nowhere did it explain what defined the tier. I was buffaloed!

On November 16th, I joined Ruth at her residence for a session with Naomi Kaminsky, a dedicated and knowledgeable volunteer with the Maryland Senior Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP). SHIP advises seniors on Medicare, Medigap, and Medicaid; and over the past few weeks, Kaminsky has been fielding endless questions from perplexed, and very nervous, seniors.

Ruth and I asked about the tiers. It turned out the first tier covers generic drugs, the second is branded drugs preferred by the insurer, and the third is un-preferred brand-name drugs. But once you get beyond the generics, each plan has different ways of determining the second and third tiers.

“This is the worst program we’ve ever seen,” Kaminsky told me, when I asked how she had prepared herself for these sessions. “I’ve been going to endless meetings, read everything, and heard speakers on all sides. When I come up with a question I can’t answer, I call and call, until I get one. It’s just awful,” she added, “and we owe it all to Congress. It’s their stupid preoccupation with the market economy. What we need is a Medicare for drugs, where you show your card, pay your co-pay, and that’s it.”

She reassured Ruth and me that we had done all we could to make some kind of choice. We ruled out the cheapest option, Humana, because of its ties with Wal-Mart. We believe in the high cost of low prices — and if we could avoid it, we didn’t want to reward Wal-Mart’s rapacious ways; furthermore, we’d heard rumor that the Humana drug pricing lists are deceptive. Ruth craved an insurer she’d heard of, like Blue Cross or AARP, but both those plans were more expensive. I handed Ruth my computer print-outs for the four options that met our criteria — low-end premiums, and coverage of her needed drugs at a relatively lower cost. She squinted at the print, and reached for her magnifier. “Leave these with me,” she apologized, “I’ll need some time to read them and think about it.”

In the end, Ruth opted for the AARP plan; despite the additional cost of several hundred dollars, she trusts the “brand” — at least she knows they’ll probably still be in existence next year. And we’d finally reached our bottom line: If her drug needs remain stable, the plan will cost her roughly $2,800 in 2006.

But as we both agreed, here’s our real bottom line: When it comes to health care, this so-called free market economy is just a cynical restructuring to serve private profit rather than public good.

It’s too much of a bad thing — and don’t you dare talk to me about privatizing Social Security!

Kim Fellner is a member of Local 1981 of the UAW and lives in Washington DC.