| From: Sam <[email protected]> Subject: Re: The Soul of Money Date: December 13, 2005 11:40:11 AM CST To: Lisa Arrastía<[email protected]>Good morning, chica, Mom and Marty hosted a brunch fundraiser for “Death Penalty Focus” on Sunday, which was uplifting. Mike Farrell (Captain B.J. Hunnicut of M.A.S.H. fame) spoke at the fundraiser. He’s a long time death penalty activist. One thing he said really stuck with me. The criminal justice system and especially the death penalty is based on the premise that the “animals” and “monsters” locked up in our prisons are reduced to the worst thing they ever did. He asked the room how we would all like to be reduced to the worst thing we ever did. Now, I haven’t murdered anyone (yet) but it’s a profound question. |

The state is an imagined collective, a theoretical “We.” We are it. Holding so much of our social strengths and relational apprehensions, it has an endowed power to manipulate our humanity and construct codifications — by which many of us operate faithfully and some oppositionally — of economics, race, sexuality, and gender. Collectively, we obey or else become forced to acknowledge the source of codification and be responsible for its insidious, deleterious, and organized systemic arrangement. Execution is an annihilation of possibility, not just the potential of human life, but the opportunity to admit the worst thing we have ever done — to each o(O)ther.

12 December 2005

Law & Order on the TNT channel. Accessible only by cable. A white cop and his Black partner look for a “Hispanic perp.” They scour a playground in the “Douglas” projects in New York; they come upon a Black girl, about ten years old, sitting slack-backed on a metal slide. She says she knows where they can find Perp, but only for $20. The white cop pays her. She tattles.

The market is everywhere, even in the small palms of little Black girls. No close-up on her face, I can still see a mess of chemically relaxed whisps of hair — unfettered, untidy, chaotic. I check the clock. A small Black child has become a fast-talking, hussy hustler. The TV steals her childhood in under two television-minutes.

13 December 2005

This morning, Stanley Tookie Williams. Executed.

|

Lethal

|

Injection1

|

It took 22 minutes to find the vein. Poking and poking, they were looking for a fat one. Agitated, Williams “grimaced.” What else grimaces? Animals grimace, contort their countenances to express pain, contempt, or disgust, because they have no words we would understand.

|

Capital punishment as witnessed execution: an exchange of death for death; life for life.

|

Maybe it satisfies a need for regaining some control, maybe it soothes an ache so deep that only death and love combined could. A victim’s stepmother was present at Williams’ capital punishment, “never took her eyes off of him,” and only began to cry when his supporters raised their Black-pride fists and declared, “The state of California just killed an innocent man.”2 Maybe the victim’s stepmother agreed. Maybe that’s why the tears.

|

Capital punishment as sanctioned, legal act by the state: an attempt to discipline; a way to enforce compliance with the state’s morality. Thou Shall Not Kill . . . . |

But the state does.

In Illinois, the courts discover 13 death row inmates wrongly convicted. Republican Governor George Ryan declares a moratorium in 2000 on all executions. In 2003, after pardoning four death row inmates, all of whom said their confessions were beaten out of them by Chicago police, Ryan rescinds the death penalty for 156 inmates. Finding the Illinois death penalty system “fraught with errors,” like Justice Blackmun in 1994, Governor Ryan decides he will no longer “tinker with the machinery of death.”3

What if Williams hadn’t really killed in this case? The fault line in capital punishment is wide, a chasm filled with all the nation’s defective and criminalizing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic judgments. The intention of the death penalty is not to gain wide social adherence to socioeconomic codifications, just as the intention to imprison is not, in effect, to rehabilitate. The idea is neither to make bodies fit into society nor to re-make ones to fit back into society. Statistics prove that the death penalty is in many ways meant to gain only specific adherence to racial and socioeconomic codifications for particular subjects.4 Modes of codification such as state surveillance to maintain order, civility, control, and uniformity are confutable. Justice Blackmun believed the death penalty could never not be “a violation on the ground of either poverty or race.”5 We the state, however, have been led to believe that it is impossible to transform (or redeem) those with nonnormative bodies — we imagine them as faulty bodies, errors in Supreme and earthly judgment. We don’t see the fault in the law and those who design and govern it. State laws, state rules, our national attitudes and behaviors demonstrate a strong belief in the sanctity of those “citizens” who remain virtually un-codified physically, racially/ethnically, sexually, and economically.

|

Economically: the state is said to represent (and protect [?]) a social collective. The state is we, but this neo-modern apparatus represents a neoliberal market gassed by anti-socialism and self-protective edicts.

|

If we commit individual state sanctioned acts of violence, decide who has been naughty and who has been nice, do we condemn the first person plural? We live within a state whose people are in various, temporary states of sedation by an iconic capital(ism). Executions are our we-the-people representative’s attempts to subvert all possible opportunities for de-centered communities to arise and rise up collectively against the market’s decrees for compliance with capitalist-based economic disparities and the violence they produce. Economic disparity and synchronal sexual, racial, and gendered illiberality are the market’s forces; they are state weapons to overcome subject-resistance and maintain market velocity. Killing the dark bodies for seemingly just reasons in our name . . . how better to amalgamate the coalition in support of the market’s impetus?

| Philosophically: in an ideologically dominant Anglo Christian “nation-state,” if we kill the dark bodies, do we eliminate the moral and sociopolitical conflicts and contradictions their very presence exposes? |

What (or whom) we get rid of when we execute this particular command of the state produces and coalesces what remains after the execution: a culturally dominant ideology and politic. Of course, what remains, too, are more dark bodies. When we kill the dark bodies, are we also hoping to cause the ruin and death of all types of social Others? What I mean is, when we killed Tookie Williams, did we kill his people’s history too? Was it all expunged? When we kill the dark bodies, does the majority we, the normative we, the white male adult we-the-state get redeemed? Because isn’t that the trust the state has forged with its ideologues: with execution, we in a sedated iconic moment, the prisoner’s body, prostrated, becomes hyper-criminalized before audience and sacrificed as lamb on a makeshift dental chair for the sins of we-the-state against all Others? It is a twisted logic for a twisted way in which the mind (and, by extension, the state body) can say, Not me and not my fault, to a whole nation of people. How else does the state redeem itself for poverty, racism, genocide, sexual violence, and war?6 As long as there is a “minority” target, capital punishment by default makes we the majority a righteous people, a community of folk who synchronously act as a social collective without moral guilt or sin.

The punishment and debauched civility with which the death penalty is committed7 allows the state an irrational moment, an un-Enlightened time-space compression where the state-as-we, we-as-state, engages in an expulsion, an exilic obliteration of dark corporeality into the indefinite, the don’t-want-to-know of the heavens, the nether region of time. Out of our time dimension. Out of our spatial extension. A dark spot. Out.

12:01 AM, 13 December 2005

| The execution chamber at San Quentin State Prison in California8 holds Williams’ dark body. An almost space- sepulcher, its structural armament is capable of withstanding the catapult of body and state cuspidor outside the nation’s mental (and perhaps physical) boundaries. |

Because the nation is imagined as a timeless borderland, it is, then, an exceptional place defying all laws of universe, nature, and humanity. |

It can codify, make rules and laws for some to circumscribe, and others to obey or suffer confinement or death. The executed are lambs sacrificed to pay for all our ethical and moral offenses of thought and action. Capital punishment is not about the executed; it is about those who are left living. |

Williams’ dark body is the putative embodiment of the worst things the state has ever done. He represents the guilt of the market in corporeal form. He is its product yet we blame Williams and all dark bodies alike. State redemption through capital punishment, an attempt to drive the worst we have ever done out of our inherent mental ability to imagine or remember.

If we kill the Black body, can the state erase history and all the injustices we commit?

Notes

1 Photograph of Stanley Tookie Williams, <http://brokenchains.us/Heroes.html>. Accessed 13 December 2005.

2 Despite Williams’ claims that he was not guilty of murdering Albert Owens, Yen-Yi Yang, Tsai-Shai Lin, and Yee-Chen Lin in 1979, he was convicted in 1981, sentenced to death. Williams’ lawyers continue to pursue his innocence despite failed appeals in state courts and failed petitions in federal courts for habeas corpus relief. The appellate court denied Williams’ appeal in 2002, but noted that he could request clemency from the Governor of California. Republican Governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger denied Williams’ request, and Williams was summarily executed by the State of California on 13 December 2005 by lethal injection at 12:35 AM.

3 Although as a member of the United States Court of Appeals, the now deceased U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun voted to enforce the death penalty (even as he “publicly doubted its moral, social, and constitutional legitimacy”), he dissented from the Court’s decision in 1994 to deny a review in the Texas death penalty case of Callins v. Collins: “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.” Blackmun went on to state “the basic question — does the system accurately and consistently determine which defendants ‘deserve’ to die? — cannot be answered in the affirmative [. . .] The problem is that the inevitability of factual, legal, and moral error gives us a system that we know must wrongly kill some defendants, a system that fails to deliver the fair, consistent and reliable sentences of death required by the Constitution.”

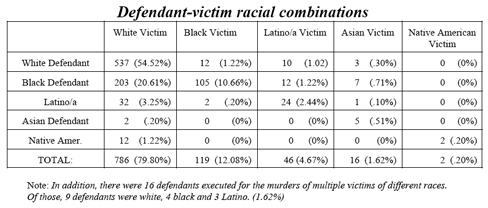

4 Ninety-seven per cent of all known executions took place in China, Iran, Viet Nam, and the USA (see Amnesty International’s “Death Sentences and Executions in 2004”). As of 1 October 2005, people of color made up 55 percent of death row inmates — the majority being Black and Latin@. This number includes Native American and Asian inmates who make up 2.33 percent (see “Death Row U.S.A.,” Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Fall 2005, page 1). In most of its studies, the U.S. General Accounting Office discovered that the race of the victim was found to “influence the likelihood of being charged with capital murder or receiving the death penalty, i.e., those who murdered whites were found more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered blacks” (see the Office’s “Death Penalty Sentencing,” February 1990, page 5). Defendants executed in the U.S. are overwhelmingly males of color, but the most shocking statistics are the ratios within the defendant-victim racial combinations. The following table is taken from the NAACP report.

Click on the image for a larger view.

5 In an interview with Ray Suarez of PBS and Professor Harold Koh of Yale Law School, Justice Blackmun stated, “I cannot see any of these death penalty cases where there hasn’t been a violation on the ground of either poverty or race. If we can ever get that straightened out, it will help. But, of course, the real answer to it is to do away with the death penalty” (see “The Blackmun Tapes,” NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, 5 March 2004).

6 The question of redemption was at issue in the clemency review by Governor Schwarzenegger. Williams argued that he deserved clemency because of his “personal transformation” while imprisoned, which he felt redeemed him for his “violent past” (see “Statement of Decision: Request for Clemency by Stanley Williams,” 12 December 2005, pages 1 and 3). In 1993, Williams recorded a videotaped message from death row supporting a truce between the Crips (which he co-founded) and the Bloods. The videotape was shown during the Hands Across Watts gang peace summit, which was attended by over 400 gang members. Furthermore, Williams created a “peace protocol” that helped to broker a truce between rival gangs in Newark, New Jersey. For his efforts and eight anti-violence/anti-gang children’s books Williams received four Nobel Peace Prize nominations. Schwarzenegger felt Williams’ “claim” of redemption “triggered” an investigation into his “atonement for all his transgressions,” and more importantly, he found it difficult to evaluate the effect of William’s peace acts. The irony in Schwarzenegger, or “The Governator” (as he is known for his role as a killing machine in the Hollywood film The Terminantor), determining Williams’ transformation and redemption is astonishing, especially in light his faulty logic. Schwarzenegger reasoned that because there remains persistent gang violence in the country one must, then, question the power, capacity, and effectiveness of Williams’ message. Williams understood the socioeconomic impetus for gangs, especially in poor communities of color. While in prison, he dedicated his life to helping reduce gang violence. I do not think Williams ever thought he would single-handedly put an end to gang violence across the nation. Can the Governator?

7 In addition to lethal injection, the heinous methods of firing squads, hangings, and electrocution are practiced by more than a dozen states including New Hampshire, Delaware, Nebraska, and Washington.

8 Photograph from California Department of Corrections, <http://people.howstuffworks.com/lethal-injection.htm>. Accessed 14 December 2005.

Lisa Arrastía, founder and former director of a progressive charter high school in Chicago, has been teaching and leading creative educational programs in independent and public schools for the last fifteen years. She holds an MA in Education and a Certificate of Advanced Study in Educational Leadership (her work with youth is the focus of a 1999 Emmy-nominated public television documentary Making the Grade). Originally from New York City, Lisa currently teaches critical white studies and essay writing at the College of St. Catherine. Her essay, “Should I Stay or Should I Go Now?,” was included in Pearl Kane’s book The Colors of Excellence (Teacher’s College Press, 2003). Lisa’s non-fiction work examines postcolonial social formations in youth that derive from the intensification of whiteness under neoliberalism.