[The Los Angeles Times recently ran a series of investigative articles by Miriam Pawel on the problems of the United Farm Workers: “Farmworkers Reap Little as Union Strays From Its Roots” (8 January 2006); “Linked Charities Bank on the Chavez Name” (9 January 2006); “Decisions of Long Ago Shape the Union Today” (10 January 2006); “Former Chavez Ally Took His Own Path” (11 January 2006); and “Real Estate Deals Pay Off for Insiders” (9 January 2006). Though her articles make no reference to previous work, they echo findings of several earlier articles on the UFW, which include Frank Bardacke, “Cesar’s Ghost,” The Nation 257.4 (26 July 1993); “Inside the UFW,” The Bakersfield Californian 8-11 May 2004; and Marc Cooper, “Sour Grapes,” LA Weekly 12-18 August 2005. Among the earliest articles discussing the lack of democracy in the UFW are “A Union Is Not a ‘Movement'” by Michael D. Yates, published in The Nation on 19 November 1977. Yates wrote of the UFW’s reaction to his article in his letter to The Nation commenting on Bardacke’s: “True to form, the union threatened to sue The Nation for publishing the article. Nothing came of this threat, but it showed how Cesar dealt with criticism” (The Nation 252.17, 22 November 1993). — Ed.]

On a Saturday afternoon last March, fifty or so United Farm Workers volunteers, myself among them, stood in circles around Cesar Chavez in the garden at La Paz, the Farm Workers headquarters in Keene, Calif. We had been at work that morning preparing the ground for planting, digging up rocks, spreading manure, listening to Cesar’s advice on using a shovel, driving a tractor, planting by the moon. Now, after lunch, he was telling us about the long struggle against the Teamsters union, how low he had felt when the union had lost its contracts, how the workers had vowed to fight back, how he had promised a group of women in Coachella that, if the UFW won back its contracts, he would make a pilgrimage to a shrine in Mexico. As he spoke, his voice cracked and he began to cry. I looked around; his daughter was crying and so were many others. I began to cry myself. As the meeting concluded, we all cheered and clapped; we returned to our work uplifted and renewed. That evening, driving into Bakersfield, I vowed to work even harder to help the union.

Within a month of that meeting in the garden, I had left the union. Virtually all of my friends had been fired by Chavez or had quit; the union’s central staff had been reduced by more than a third. I was disappointed, even disillusioned. What follows here is an analysis of what I believe are serious problems now confronting the UFW.

In The New York Times Magazine of September 15, 1974, Winthrop Griffith wondered if the UFW could survive the Teamster invasion of its territory. Through “sweetheart” deals with growers, the Teamsters had stolen most of the 200 or so contracts won by the UFW in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Along with the contracts had gone members and dues and the UFW, always strapped, now appeared too poor and too demoralized to confront the powerful Teamsters.

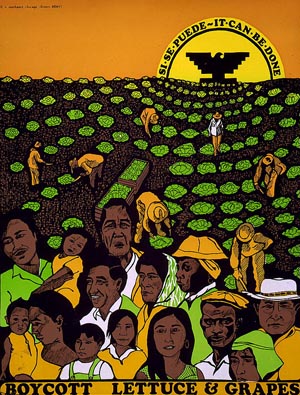

The doomsayers, however, underestimated the tenacity and skill of Cesar Chavez and his small but fanatically zealous staff, as well as the fierce allegiance of the workers to Chavez and the UFW. Knowing that, given the chance, farm workers would vote for his union, Chavez set about giving them that chance through what developed in time into a tripartite strategy. First, offices were established in every major city to promote a boycott of all crops, but especially grapes and lettuce, grown with nonunion or Teamster labor. Second, the union stepped up its agitation for a state law in California that would guarantee to farm workers election and bargaining rights similar to those granted most other workers by the NLRA. Third, a direct counterattack was staged against the Teamsters. Several multimillion-dollar legal suits were filed against them and various employers, and effective anti-Teamster propaganda was produced and disseminated — most notably the film, Fighting for Our Lives.

The doomsayers, however, underestimated the tenacity and skill of Cesar Chavez and his small but fanatically zealous staff, as well as the fierce allegiance of the workers to Chavez and the UFW. Knowing that, given the chance, farm workers would vote for his union, Chavez set about giving them that chance through what developed in time into a tripartite strategy. First, offices were established in every major city to promote a boycott of all crops, but especially grapes and lettuce, grown with nonunion or Teamster labor. Second, the union stepped up its agitation for a state law in California that would guarantee to farm workers election and bargaining rights similar to those granted most other workers by the NLRA. Third, a direct counterattack was staged against the Teamsters. Several multimillion-dollar legal suits were filed against them and various employers, and effective anti-Teamster propaganda was produced and disseminated — most notably the film, Fighting for Our Lives.

Chavez’s strategy gradually began to bring results: the boycott cut into the profits of grape and lettuce growers; the sympathetic Brown administration helped to lobby a remarkably liberal labor law through the California legislature; the battle with the Teamsters produced nationwide support for the UFW and a black eye for the already tarnished Teamsters. After the enactment of the new law, the UFW began winning representation elections throughout the state, losing only when Teamster-grower collusion and intimidation prevented it from getting its message to the workers. Frightened, the growers and their Teamster allies got the state legislature to refuse to vote a supplemental appropriation for the Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB), the agency charged with enforcing the law. Chavez countered this move with a public initiative (Proposition 14) that would incorporate the labor law into the state Constitution, thereby insuring yearly appropriations for the ALRB. The initiative failed, but it forced the growers to defend the existing law, making it unlikely that they will be able to amend it or prohibit adequate funding for the ALRB, at least for the next few years. Meanwhile, the UFW continued to win elections and to press its lawsuits, finally compelling the Teamsters last March to agree to abandon agricultural organizing throughout the West and to relinquish most of its existing contracts when they expire.

These events make the UFW’s future prospects brighter than ever before. There is no doubt that it will attract thousands of new members, that thousands of campesinos will get their first union contracts, and that large sums of money will flow into the UFW treasury, providing support for further organizing in California and other states. Increased UFW strength and power might in turn help to liberalize and invigorate the entire labor movement as other workers are moved by its example.

All of this sounds encouraging, but after spending a few months working at La Paz, I am not particularly optimistic. Chavez has performed a miracle, but the union is still beset by a host of serious problems. I think many of them stem from the personality and leadership of Chavez.

The prospect of a powerful Farm Workers Union frightens growers, who have always depended for their profits on low wages and the exploitation of racial minorities, and it is now unlikely that they can prevent elections from being held or the UFW from winning them. However, neither elections nor UFW victories will render employers helpless; they still have available many tactics to combat and harass a union, even if it does legally represent workers. They can refuse to bargain seriously, offering contract proposals that no union could accept. They can refuse to negotiate items that might in any way restrict their “managerial prerogatives.” Should they eventually sign a contract, they can interpret it narrowly, or simply not abide by it at all. Finally, these short-term strategies can be complemented by a longer-range program of increased mechanization to undermine the very basis of the union’s existence, its membership.

These practices are in fact being employed. In many instances, growers have successfully stalled negotiations more than a year, and violations of contracts are common. A quick run through the agricultural journals will convince a reader of the rapid pace of mechanization:

To contest any such actions by the employers, the union must obviously preserve its militance; it must have workers ready to picket and to strike. But, now that labor relations in California agriculture are legally regulated, it is not always possible to enforce a contract with what would be illegal job action. In addition, since the work force consists in large part of migrant workers performing seasonal work, there are often no workers to picket and strike. Therefore, to buttress the organized collective force of farm workers, it is necessary that the union establish and maintain a skilled administrative staff. Contract negotiations, for example, require staff persons with many kinds of expertise: the ability to do economic research, to keep adequate records, to stay abreast of developments in other areas, to train workers to participate in negotiations, to take good notes of meetings, to write well. Similar skills are needed for contract administration and enforcement. A union today must have accountants, experts in management, lawyers, personnel officers, researchers. Inevitably, once a union is securely established, many of its important activities take place in courtrooms, in meeting rooms, at desks, in offices.

The UFW is not well administered. During my stay I observed that research projects were generally superficial and haphazard. Records were either not kept or strewn about, stuffed in boxes, stored at random in basements and cubbyholes. Negotiators often took no notes of their meetings, or took notes so poor as to be useless. Repeatedly, negotiators in one part of the state were unaware of agreements reached elsewhere; generally speaking, communications throughout the union were woefully slipshod. More seriously, the union seldom allowed one negotiator to see a contract through from start to finish, thus delaying negotiations for days and months. Also, with few exceptions, negotiators could not make binding agreements on even routine matters without personal approval by President Chavez. The contracts themselves were often poorly worded or badly translated; translators received no training in the rudiments of contract analysis and frequently did not know what their translations meant. I remember talking with a co-worker in charge of translations who had not realized in a whole1 year of work that many of the articles in a majority of the contracts had exactly the same wording.

To compound these difficulties, chronic turnover plagues the administrative staff; two years with the union qualifies one as a veteran. This means that few people remain with the union long enough to master their jobs, to become experts. It was always sad when a skilled volunteer left, to be replaced by a greenhorn who would make the mistakes inevitable for newcomers.

Observers of the union have offered various explanations for the UFW’s administrative deficiencies. The UFW is young, and has been forced to expend its limited resources against formidable odds just to organize farm workers. Administration presents new problems and requires new capabilities which take time to understand and to acquire. The high turnover might be attributed to the fatiguing work schedules, low pay and Spartan living conditions that have been the lot of UFW volunteers. But as organizing becomes easier and the union’s treasury grows, working conditions for staff will improve and turnover will decline. There is talk within the union of paying volunteers a regular salary; at present, only union doctors and attorneys receive salaries.

Such explanations skirt the main point. The primary reasons for administrative chaos within the UFW are to be found in the personality and the social philosophy of Cesar Chavez. He is magnetic, autocratic and at bottom more concerned to build a social and political movement than a trade union.

Chavez’s dynamic and imaginative leadership has given him nearly absolute control of the union. The UFW constitution allows considerable rank-and-file participation in union affairs, but in fact Chavez’s word is law. Authority is seldom delegated; members of the executive committee are not free to act without his permission. In addition, he has complete control over the volunteers, who comprise the bulk of the union’s organizing, administrative and boycott personnel. These people, especially the ones at La Paz, are Chavez’s personal retinue. They perform invaluable work for the union, but they also owe allegiance to Chavez. He selected them; he can dismiss them at will and frequently does. Those who criticize him are perceived as threats to himself and to the union (indeed, in his mind there is little separation between the two). In the past year there have been at least two mass firings: one just following the Proposition 14 campaign, and another during the first weeks of April 1977. Dedicated, hard-working men and women, essential to the smooth functioning of the union, were accused, on little or no evidence, of being radicals, spies for the employers, troublemakers, complainers. They were told to leave the union, or were pressured into quitting. One man, a talented plumber and a friend of mine, was physically removed from a meeting at La Paz because he had demanded that the union support its charges that he was a company spy. He was turned over to police in Mojave, Calif., charged with trespassing.

Much of the poor administration of the union stems from the climate of unrest that these periodic dismissals create. And they in turn are the direct result of Chavez’s need to have absolute control over the union and the unquestioning loyalty of its members. Since personal loyalty is ultimately more important than ability and independent judgment, it is not uncommon for those of slight talent or maturity to rise to prominent positions in Chavez’s “inner circle.” Many persons close to Chavez at La Paz are relatives of his or other UFW leaders’.

This is not to say that Cesar Chavez is simply a Latin “caudillo”; he is also a social visionary. That is another reason for Chavez’s purges, his distrust of “experts,” his seeming unwillingness to let the union’s administration operate normally. Chavez does not want the UFW to become just another trade union, dominated by bureaucrats. The UFW must be a social movement, encompassing wider goals than bargaining collectively for higher wages and better working conditions. Chavez realizes that mechanization is going to decimate the ranks of his farm workers. What will become of them when no trade union can represent them? There must be a social movement to embrace them and through which they can struggle for fundamental social change. Chavez is vague about the platform of his movement, but he seems to favor some type of cooperative farming (he has extensive knowledge of cooperative movements throughout the world), workers’ control and a communal life style. However, he is certain about the people who will make up the movement: they will be single-minded, totally committed, willing to sacrifice themselves for the good of the whole. Chavez believes that a movement must always be in a state of tension; persons in it must feel that they are under siege, at war with the larger society. Those who lack these qualities will be ruthlessly weeded out, recurrent purges serving as “purifying rituals” by which the movement reconstitutes itself and reaffirms its basic principles.

Unfortunately, conducting the affairs of a trade union as if it were a social movement risks making the union dysfunctional. An argument can be made that the United States much more desperately needs a social movement than it does another trade union, though a better case can be made that both are necessary prerequisites for social change. In any case, it must be understood that unions and movements are not the same; they must coexist and cooperate, but they also must have considerable autonomy. By their nature, unions have to be more narrowly defined than movements; they serve basically as defensive agents in the fight against employers. Movements, on the other hand, must be more broadly based, offensive organizations, trying to forge a new society. It would seem impossible for either to function effectively if both are controlled by the same person, and neither will last very long if founded upon personal rule of a charismatic leader. The UFW suffers as a trade union not only because it is run by an autocrat but because it is being forced to be what it cannot possibly be.

Perhaps, then, it would be better for Cesar Chavez to relinquish control of the union and concentrate his energy upon building a social movement. Yet Chavez’s movement philosophy may not appeal very widely in the United States. It is, as I have indicated above, essentially authoritarian. Time and again, during community meetings at La Paz, Chavez expressed admiration for totalitarian groups, especially religious communities like the Trappists. Recently, he has been much enamored of Synanon, a California-based community founded to cure drug addicts, and extremely authoritarian.

I am pessimistic about the future of the UFW and the movement for which it has been the vehicle to date. I fear that at present neither could survive without Chavez; they are too much dominated by his overwhelming personality, much as the United Mine Workers once was dominated by John L. Lewis. And I doubt that mass support can be won for any organization or movement in the United States that is not founded upon participatory democracy and a depersonalized power structure. Needless to say, Cesar Chavez has proven his critics wrong before. I am not eager to be proven right.

Michael D. Yates is associate editor of Monthly Review. He was for many years professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. He is author of Longer Hours, Fewer Jobs: Employment and Unemployment in the United States (1994), Why Unions Matter (1998), and Naming the System: Inequality and Work in the Global System (2004), all published by Monthly Review Press. This article was originally published in The Nation 225.17 (19 November 1977) and is republished here with the author’s permission.