The United Transportation Union, which represents railroad conductors and some engineers, reports that negotiations with the railroad corporations had broken down over the issue of crew reduction. The carriers are demanding the implementation of one-person train crews for many routes on the US freight rail system. The current standard train crew is two, an engineer and conductor. Engineers are in the main represented by the Teamster-affiliated Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen. So seriously do the UTU and the BLET regard the threat posed by the railroads that they have even ceased what was becoming one of the most fractious inter-union conflicts going on in the US trade union movement in order to fight crew reduction.

The decline of the number and percentage of organized workers in the United States is news to no one. Only 12.5 percent of wage and salary workers are union members, and less than 8 percent of the workers in the private sector are organized (Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union Members in 2005,” 20 January 2006).

Rail labor, unlike the rest of the US workforce, is still largely organized. The problem is that the number of rail workers has been reduced drastically (for which a slight uptick last year hardly compensates), even while the total freight traffic has grown dramatically.

The peak of railroad employment came in 1920, when 2,000,000 people worked in the industry. In 1916, the railroad track system reached its greatest extent: 254,000 miles. 98 percent of all intercity passenger and 77% of all intercity freight traffic was shipped by rail. Almost every family in America had a father, brother, uncle, or cousin working for the railroad. Although they were a definite minority, women also were working for the railroad, mainly as station agents, clerks, secretaries, and telegraphers.

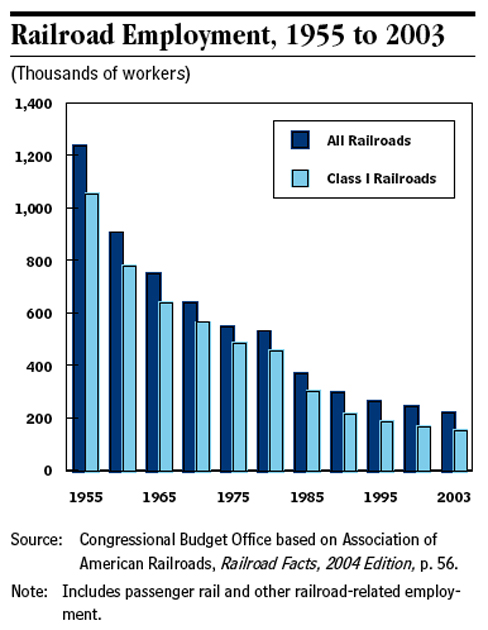

In contrast, the Railroad Retirement Board lists the number of all active railroad employees, including passenger workers and management paying into the system, as 238,000 in 2001, 229,000 in 2002, 225,000 in 2003, 227,000 in 2004, and 233,000 in 2005. The Congressional Budget Office graphically charts the decline from 1955 to 2003:

Source: Congressional Budget Office, “Freight Rail Transportation: Long-Term Issues,” January 2006

Locomotive engineers, conductors, and all other railroad transportation workers numbered 108,050 in 2004, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates. The number of these workers in freight rail would be even smaller.

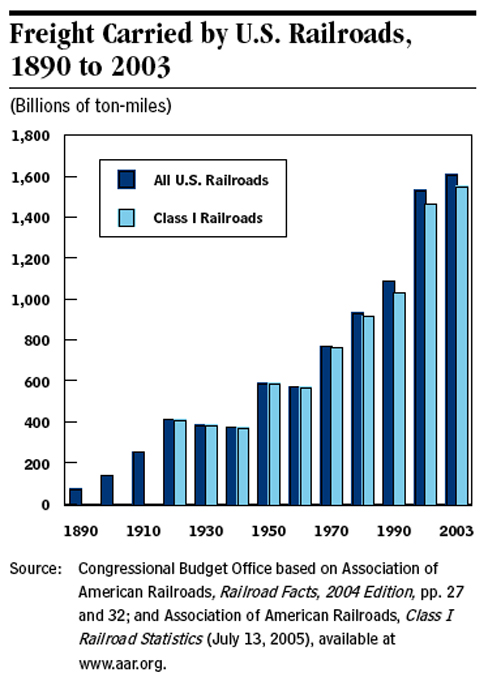

Yet while rail employment has fallen to one tenth the level of its peak, freight ton miles hauled by railroads has increased from 141 billion ton miles in the beginning of the twentieth century to 1.6 trillion ton miles in 2003. This is a staggering 11 times the freight moved 100 years ago, despite the fact that there was no trucking industry to speak of then.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, “Freight Rail Transportation: Long-Term Issues,” January 2006

Railroads carried 1.8 billion tons of freight in 2003. They move about 1.7 million carloads of hazardous materials annually, about 5% of all freight rail traffic. This means that nearly 0.25 million tons of hazardous material are on the move on the US rail system every day. (That’s a very conservative estimate, as the figure of “1.7 million carloads” comes from the railroad industry seeking to reassure the public of rail safety. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of Hazardous Materials Safety estimated in 1998 — almost a decade ago — the daily total weight of hazmat carried by rail to be 1,136,748 tons.) This includes the nation’s capital, Washington, DC, where the CSX railroad moves hazardous freight routinely through the city, about 8,500 chemical cars a year. The city government and the railroads have been engaged in a dispute about this routing.

What sorts of hazardous material may be passing through your community? According to Greenpeace,

Ninety percent of the transportation risk of the most dangerous or toxic-by-inhalation (TIH) materials is represented by just six chemicals according to a 2000 risk assessment by Argonne National Laboratories. These chemicals are: chlorine, ammonia, sulfur dioxide, hydrogen fluoride, fuming sulfuric acid and fuming nitric acid. Argonne also estimated that chlorine alone accounts for 58.5 percent of TIH risk of fatality. . . . Chemical facility disaster reports to the EPA show that the release of a toxic gas cloud could spread 14 miles in an urban zone and up to 25 miles in rural terrain. According to a 2000 report by the EPA which first identified over 100 facilities that threaten a million or more people, “the high number of facilities in both class intervals is primarily due to the prevalent use of 90-ton rail tank cars for chlorine storage in the United States.” (“Greenpeace Comments on DC Rail Security,” 30 September 2005)

And what happens when trains carrying hazmat shipments malfunction? In 2005, nine people were killed and thousands evacuated when a Norfolk Southern train derailed and a chlorine car split open next to a mill in Graniteville, South Carolina. That’s just one example.

A Hazardous Material Rail Tank Car

Even as the railroads propose crew reductions, in the past three years, train collisions increased by more than 42 percent, and employee fatalities are up by 17 percent, according to the Federal Railroad Administration data. For the period January-September 2005 (9 months), the FRA reports there were more than 2,200 train accidents, some 1,200 yard accidents, 1,655 train derailments, and 21 rail-employee fatalities.

The railroad corporations predict tens of millions of dollars in savings by not hiring and reducing crew size to one person, who would also be required to leave the train to operate remote control in switching operations and tend to unexpected mechanical problems.

The danger of reduced crews is primarily from fatigue. Fatigue already is a severe problem in the railroad industry. Lack of train crew personnel requires railroads to demand employees work up to 30 days without rest periods. It is not uncommon for train and engine service employees not to receive even six hours of uninterrupted sleep daily. One can only imagine the struggle it must be to stay awake late at night as mile after mile of rail disappears under your cab. A moment of “micro-sleep” could mean missing a signal, or not seeing a person or vehicle in the tracks ahead, as you pass through cities and small towns, the smaller ones without even a rail crossing gate.

For a dramatic illustration of the dangers of a one-person crew policy, let’s not forget the runaway train incident in Ohio a few years ago when an engineer, temporarily alone on the CSX freight train, attempted to throw a switch and jump back on. He had throttled up the locomotive by accident before he got off, and the train took off without anyone on board, traveling 66 miles before it could be stopped.

An article in the Chico, Montana newspaper vividly describes the fears of a community when the Union Pacific Railroad decided to increase the speed of trains passing through to 70 miles per hour.

In less than four years, the speed limit on trains passing through Chico has increased from 25 mph to 70. And there is nothing anyone here can do about it; except, say Union Pacific folks, to make sure you look both ways before crossing the tracks.

But is that enough in a town with a reputation among train engineers as a dangerous run because of drunks, trespassers, abandoned shopping carts, and the occasional flaming couch that sometimes end up on the tracks?

Running along the athletic fields on the Chico State University campus, there is a pedestrian/bicycle path that crosses the railroad tracks and heads west along some student apartments. One day last week, News & Review photographer Tom Angel and I visited the path to get photos and a feel for what it is like when a train passes through at 70 mph.

Within five minutes, we heard the horn of an approaching train. When the signal at the pedestrian crossing sounded, students heading to or from class reacted by running across the tracks to avoid a couple-minute delay. The train whooshed by, shaking the ground and rocking on the tracks as it pulled flat cars stacked with lumber, black cylindrical tanks carrying liquid propane and rust-red boxcar loads of Canadian wheat.

Angel and I agreed, based on the turbulence and feel we experienced, that the train had probably passed at 70. We were wrong. Forty minutes later, we heard the approach of a second train. This one came much faster, and its passing was much more violent.

In truth, it was a stunning experience to stand within 20 feet of this massive, thousands-of-tons-heavy machine screaming through the middle of Chico. (Tom Gascoyne, “Trouble Ahead?” Chico News & Review 17 April 2003)

Scenes like this are repeated daily all over the United States. Whether in small towns like Chico or vast metropolitan areas like Washington, DC, the movement of freight by rail never stops. Millions live, work, and sleep next to the tracks where this cargo, some of it lethal, stays on the rails thanks to the work of only several hundred thousand railroad workers, operating the locomotives, maintaining the tracks and mechanical equipment, twenty four hours a day, three hundred and sixty-five days a year. A moment of sleepiness, a loose rail, even a missing grease plug in a traction motor could mean the difference between life and death for thousands if the accident happens in the “wrong” place.

Several hundred thousand workers in a country of nearly three hundred million are but a drop in the bucket politically speaking. No national election is going to turn on the railroad worker vote. In a few areas, like Chicago or Minneapolis for example, enough railroad workers live to perhaps influence a congress member or two to speak up for them occasionally. Where can they turn then in this struggle with the wealthy railroad companies, whose money flows freely through the halls of power in Washington?

It should be obvious that the ally of the beleaguered railroad worker must be those people of the “trackside communities” living often obliviously next to that tank car full of chlorine rolling by in the night. Rail labor must find ways to reach the trackside working people and awaken them to the true risks of the railroad companies’ plans for staffing reduction, which would put so many lives in jeopardy.

Labor needs to sound the alarm before it is too late. Whether it is through letters to the editor, picket lines, rallies, or even strike action, we need to let the people know that a red line is about to be pegged on the meter, taking us into a danger zone.

Railroad workers no longer have the numbers to threaten politicians at the ballot box. But the people next to the 5 million tons of freight per day we move do. If we could unite with “trackside communities” around the safety issue, we could become a power to be reckoned with.

Jon Flanders is a member and former president of IAM LL 1145 and a member of the Troy Area Labor Council, AFL-CIO.