Jacques Tardi, à qui l’on doit notamment l’extraordinaire La guerre des tranchées, s’est lancé en 2001 dans l’adaptation en bande dessinée du roman libertaire de Jean Vautrin sur la Commune de Paris, Le cri du peuple*. Le projet devait tenir en trois tomes, mais Tardi a finalement décidé de consacrer à l’insoutenable répression des Versaillais durant la semaine sanglante un quatrième et dernier tome, qui vient de paraître. Jacques Tardi, à qui l’on doit notamment l’extraordinaire La guerre des tranchées, s’est lancé en 2001 dans l’adaptation en bande dessinée du roman libertaire de Jean Vautrin sur la Commune de Paris, Le cri du peuple*. Le projet devait tenir en trois tomes, mais Tardi a finalement décidé de consacrer à l’insoutenable répression des Versaillais durant la semaine sanglante un quatrième et dernier tome, qui vient de paraître.

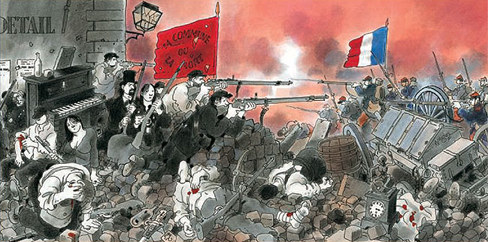

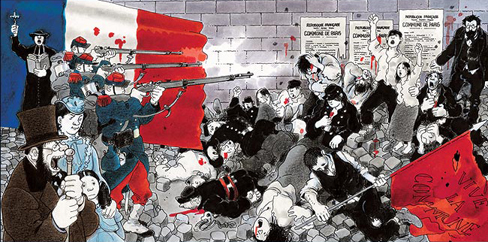

C’est avec talent que Jacques Tardi a adapté à la bande dessinée le roman de Vautrin, qui fait revivre le Paris de 1871, avec ses espoirs, ses joies et ses amours, comme ses souffrances, ses désillusions et ses pleurs. Si l’œuvre romanesque de Vautrin et Tardi ne cache pas un parti pris tout à fait clair pour les insurgés du 18 mars, elle n’en demeure pas moins exemplaire dans son attachement à respecter les faits historiques. Cet hommage au «petit peuple» met en scène toutes sortes de personnages fictifs, qui côtoient des figures historiques de la Commune, comme Vallès, Ferré, Varlin, Bergeret et, bien entendu, les généraux du «petit Foutriquet», alias Adolphe Thiers, président du Conseil. Ainsi, ce sont plusieurs destins croisés et autres petites histoires nées de l’imagination de Vautrin qui s’intègrent habillement [sic] au récit historique, donnant à ce polar, une dimension particulièrement touchante et haletante. La République proclamée Le premier tome «Les canons du 18 mars», sorti en 2001, traite des premiers jours de l’insurrection, lorsque le peuple de Paris s’empare des canons de Montmartre et que les soldats se rallient à la cause du peuple, forçant le gouvernement à s’enfuir à Versailles. Le pouvoir conservateur et monarchiste était renversé et le 28 mars, la République proclamée. On croise au fil des pages l’institutrice Louise Michel, Jules Vallès ou encore le peintre Courbet, mais on découvre surtout les personnages centraux, pour la plupart librement imaginés, des différentes énigmes qui vont traverser l’ensemble du récit: le capitaine Tarpagnan, qui prend fait et cause pour l’insurrection à Montmartre et qui tombe amoureux de la belle Gabriella Pucci, alias Caf’Conc, prostituée tenue par La Joncaille, patron du gang de l’Ourcq, le notaire Horace Grondin qui veut venger la mort de sa fille dont il croit Tarpagnan responsable, ou encore le serrurier-cambrioleur Fil-de-fer. . . Le désespoir s’installe peu à peu au cours du tome second, «L’espoir assassiné», qui met en scène la riposte des Versaillais qui commencent à attaquer pour de bon les insurgé-e-s. L’atmosphère devient lourde et, tandis que les fils de la sombre intrigue qui entoure la mort de la fille de Grondin commencent à se délier et que l’enquête sur le gang de l’Ourcq avance, on commence à pressentir la fin de la Commune… Les tensions arrivent à leur paroxysme dans le troisième tome, «Les heures sanglantes». Les troupes versaillaises avancent sur Paris et les batailles s’intensifient. La fin de la Commune est proche et la conscience parmi les insurgés que cette fin sera des plus brutales se répand, sans pour autant altérer la ferveur avec laquelle ils entendent défendre leur république. Le dessin de Tardi illustre admirablement bien le désordre régnant à Paris, entre le 20 et le 24 mai 1871, comme la désorganisation des communards, qui leur sera fatale face à la barbarie des forces réactionnaires, tandis que les héros de ce récit continuent à affronter leurs destins respectifs… Paris à feu et à sang «Le Testament des ruines», quatrième et dernier tome du Cri du peuple, débute le mercredi 24 mai 1871 à 3 heures du matin, dans un Paris à feu et à sang, pour se terminer avec la mort de la Commune quatre jours plus tard. Quatre jours durant lesquels les intrigues entre les différents protagonistes se délient pour arriver à leur fin et quatre-vingts pages pour plonger le lecteur dans l’horreur et la cruauté la plus bestiale… Le cri du peuple est incontestablement un des grands chefs-d’œuvre de Tardi. Personne d’autre n’aurait sans doute pu restituer aussi bien que lui le climat obscur et sombre de cette période trouble. Ses somptueuses planches nous plongent dans l’atmosphère de ces neuf semaines de luttes, de rêves et d’utopies portées par ce petit peuple gouailleur de Paris. Et quand bien même la Commune a été brutalement écrasée, Le cri du peuple nous rappelle avec talent que ses idéaux ne sont pas morts avec elle. * Tardi, Le cri du peuple, quatre tomes, Casterman, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004. |

Jacques Tardi, to whom we owe the extraordinary The War of the Trenches among others, launched, in 2001, the comic strip adaptation of the libertarian novel about the Commune of Paris by Jean Vautrin, The Cry of the People.* The project was to be completed in three volumes, but Tardi eventually decided to devote the fourth and last volume, which just appeared, to the unbearable repression by the Versailles troops during the bloody week. Jacques Tardi adapted the novel of Vautrin to the comic strip medium with flair, making the Paris of 1871 come alive, with its hopes, its joys, and its loves, as well as its sufferings, its disillusions, and its tears. If the romantic oeuvre of Vautrin and Tardi makes no secret of clearly taking the side of the rebels of 18 March, its devotion to respect historical facts remains no less exemplary. This homage to the “little people” puts on stage all kinds of fictional characters, who rub shoulders with historical figures of the Commune like Vallès, Ferré, Varlin, Bergeret and, of course, the generals of “the Pipsqueak,” alias Adolphe Thiers, president of the Council. Thus, there are several destinies that intersect one another and other small stories born of the imagination of Vautrin that are skillfully integrated into the historical narrative, giving a particularly affecting and gripping dimension to this thriller. The Republic Proclaimed The first volume “The Cannons of 18 March,” published in 2001, treats the first days of the insurrection, when the people of Paris seized the cannons of Montmartre and the soldiers rallied to the cause of the people, forcing the government to flee to Versailles. The conservative monarchist power was overthrown, and, on 28 March, the Republic was proclaimed. We come across the teacher Louise Michel, Jules Vallès, or even the painter Courbet in the pages of The Cry of the People, but above all we discover the central characters, for the most part freely imagined, with various enigmas which are going to unfold through the whole of the narrative: Captain Tarpagnan, who takes sides with the insurrection in Montmartre and who falls in love with beautiful Gabriella Pucci, alias Caf’Conc, a prostitute kept by La Joncaille, the boss of the l’Ourcq gang, the notary Horace Grondin who wants to avenge the death of his daughter for which he believes Tarpagnan was responsible, or the locksmith-burglar Fil-de-fer. . . . Despair sets in little by little in the course of the second volume, “The Murdered Hope,” which depicts the response of the Versailles troops who commence to attack the rebels for good. The atmosphere becomes heavy and, as the threads of the dark intrigue which surrounds the death of the daughter of Grondin start to unravel and the investigation into the Ourcq gang progresses, one begins to have a presentiment of the end of the Commune. . . . The tensions come to head in the third volume, “The Bloody Hours.” The troops of Versailles advance on Paris and the battles intensify. The end of the Commune is near and the awareness that this end will be very brutal spreads among the rebels, without diminishing the fervor with which they intend to defend their republic. The drawing of Tardi admirably illustrates the disorder reigning in Paris, between 20 and 24 May 1871, like the disorganization of communards, which will be fatal for them facing the barbarity of the reactionary forces, while the heroes of this narrative continue to confront their respective destinies. . . . Paris on Fire and in Blood “The Testament of the Ruins,” the fourth and last volume of The Cry of the People, begins on Wednesday, 24 May 1871, at 3 in the morning, in Paris on fire and in blood, to end with the death of the Commune four days later. Four days during which the plots of various protagonists unravel and come to their end; and eighty pages to plunge the reader in horror and the most bestial cruelty. . . . The Cry of the People is incontestably one of greatest masterpieces of Tardi. Without doubt, no one else could have reconstructed the dark and murky climate of this turbulent period as well as him. Its sumptuous panels immerse us in the atmosphere of these nine weeks of struggles, dreams, and Utopias kept up by these street-smart commoners of Paris. And even though the Commune was brutally crushed, The Cry of the People reminds us that its ideals did not die with it. * Tardi, The Cry of the People, four volumes, Casterman, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004. |

The Cry of the People: Book Cover Art

This essay by Erik Grobet first appeared in solidaritéS (No. 53) on 19 October 2004. Translation by Yoshie Furuhashi (@yoshiefuruhashi | yoshie.furuhashi [at] gmail.com).

Last year, the four volumes of The Cry of the People were republished as one big volume, Intégrale Le cri du people (Casterman, 2005). The compilation comes with a CD Chansons de la Commune, 1871, which includes such songs as “La canaille,” “Au mur,” “Communarde,” “Semaine sanglante” (sung by Francesca Solleville), “Le Drapeau rouge” (also by Solleville), “Elle n’est pas morte” (by Solleville), “Tombeau des fusillés” (by Serge Utgé-Royo), “Sur le temps des Cerises” (by Utgé-Royo), “Le temps des cerises” (by Dominique Grange), “L’internationale” (also by Grange), “L’insurgé” (by Bruno Daraquy), and “Le mur” (recited by Jacques Tardi).