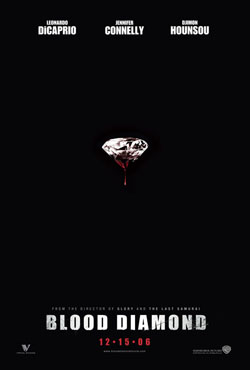

With awards season now upon us, Leonardo DiCaprio seems poised for a walk down the red carpet at next month’s Academy Awards. Having already garnered two Golden Globes nominations for best actor (one for his performance in The Departed and the other in Blood Diamond), an Oscar nod is likely to follow. Many filmgoers who’ve been watching Mr. DiCaprio’s slow assent to maturity from his days as a teen idol in the blockbuster Titanic have been impressed with his recent offerings, which elevate the young Hollywood heartthrob to the ranks of a serious actor. His powerful performance in Martin Scorcese’s highly-acclaimed film, The Departed, is compelling while also at times disarming in its vulnerability. But while Mr. DiCaprio is often captivating in the more recent Blood Diamond, neither the film nor his performance manages to reach the high bar set by his portrayal of undercover cop Billy Costigan in the Scorcese film.

There is, nevertheless, much to like about Blood Diamond. It is a film with an important mission: to bring to cineplexes all across suburban America the unwelcome news (to many, alas) that the glitzy diamond industry, which has perpetuated the lore of diamonds as the symbol of eternal love, has a very ugly underbelly. Set in the late 1990s during the civil war in Sierra Leone, the plot revolves around Danny Archer (Leonardo DiCaprio), a white African smuggler, who learns that a very large pink diamond has been buried near a diamond mine. Its location is known only to Solomon Vandy (Djimon Hounsou), a mine worker who managed to bury it immediately before being captured and hauled off to jail. What follows is somewhat predictable: Archer bails Vandy out of jail in order to compel him to reveal the location of the diamond and then, ostensibly, to split the profits. Enter the lovely Jennifer Connelly, an idealistic journalist named Maddy, who is determined to expose the real story of conflict diamonds in Africa. She agrees to help Danny in exchange for insider information on the inner workings of the diamond industry.

There is, nevertheless, much to like about Blood Diamond. It is a film with an important mission: to bring to cineplexes all across suburban America the unwelcome news (to many, alas) that the glitzy diamond industry, which has perpetuated the lore of diamonds as the symbol of eternal love, has a very ugly underbelly. Set in the late 1990s during the civil war in Sierra Leone, the plot revolves around Danny Archer (Leonardo DiCaprio), a white African smuggler, who learns that a very large pink diamond has been buried near a diamond mine. Its location is known only to Solomon Vandy (Djimon Hounsou), a mine worker who managed to bury it immediately before being captured and hauled off to jail. What follows is somewhat predictable: Archer bails Vandy out of jail in order to compel him to reveal the location of the diamond and then, ostensibly, to split the profits. Enter the lovely Jennifer Connelly, an idealistic journalist named Maddy, who is determined to expose the real story of conflict diamonds in Africa. She agrees to help Danny in exchange for insider information on the inner workings of the diamond industry.

Now the film turns into something of a road/adventure movie, as the threesome heads into the jungle. There are graphic and memorable scenes throughout of mass slaughter and destruction, armed attacks and ambushes, countless corpses and fleeing refugees. Lest we forget, however, that sex appeal is what keeps the reels rolling, the film offers just a bit of skin, perhaps to make the mayhem a little more palatable. “This is what a million people looks like,” says Maddy as the camera pans over a sea of heads amassed in a refugee camp. But the pathos of human suffering is juxtaposed here with a shot of Connelly, whose blouse appears to be strategically unbuttoned just so, diverting the viewer’s attention almost willy-nilly. It isn’t long now before the sexual tension between Maddy and Danny grows until we are as intrigued by the possibilities of this romance as we are concerned for the plight of the innocent child soldiers who are indoctrinated and forced to kill or be killed if they refuse to cooperate. Nonetheless, to the film’s credit, the pair does not end up tussling in a hammock, as one might expect, and Danny manages to win us over in the end, despite his rather dubious and at times irritating accent.

Blood Diamond is one of many films about black Africa in which the black Africans themselves are used as backdrop for the action (a point that bears repeating) and Africa appears as another “heart of darkness” to be exploited by global industry. This notion is unwittingly underscored in a moment of near comic relief when a survivor in a devastated village muses ironically: “Let’s hope they don’t discover oil here.”

Although Hollywood rarely seems to have any profound impact on the real world in spite of its do-good efforts, the broad appeal of this film has succeeded in bringing attention to the ways the diamond industry keeps prices artificially inflated and to the much-touted Kimberly Process, designed to certify that diamonds are conflict-free — a process, according to independent sources, still riddled with problems. Not surprisingly, DeBeers and the World Diamond Council saw the frontal attack from the film coming and early on began a vigorous public relations blitz that, among other tactics, included sponsoring hip-hop artist Russell Simmons’ now notorious trip to Africa. The criticism can be summed up in Simmons’ accusation that the film was “scaring people away from diamonds” — and need we add — possibly from his own merchandise line. He was quick to mention that none other than Nelson Mandela stressed the importance of diamonds to African countries’ economies. Indeed, Africa needs its diamonds, but it seems Mr. Simmons has missed the point entirely. As holiday sales have shown, diamonds do seem to be forever, and the industry, unlike human casualties of conflict diamonds, remains intact — alive, well, and extremely profitable.

The review by M. C. Saavedra came to MRZine via Michael Yates.

|

| Print