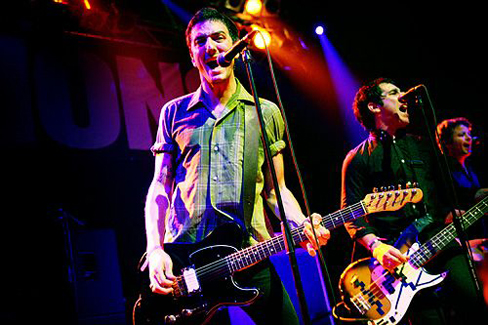

It’s a rare thing to find a group of musicians who are willing to stick to their guns like Radio 4 has. Independently minded, with an eclectic sound and lyrics that eloquently call for radical social change, they have spent the better part of a decade carving out a niche for themselves.

Not an easy thing to do. Today’s record companies and music journalists are constantly looking for an “angle” (“how can we sell this?”) with musicians, and any band with a unique sound or social message can find itself at odds with the industry. Radio 4 has both. And yet they have weathered pigeonholing from the industry surprisingly well. They are often described as “post-punk,” but their sound goes beyond the boundaries defined by the New Wave movement of the 80s. Reggae, Afrobeat, house and dance music all find their way into their style. The result is an energetic and irresistibly catchy sound that has gained attention in the “indie-rock” scene, though it is better described as “Danceable Punk.”

|

Hailing from Brooklyn, their second album, Gotham! (considered by many to be their breakout), was released right on the heels of September 11th. The group had long been concerned with trends in New York City like gentrification, poverty, and police brutality. But in the aftermath of 9/11, songs like “Calling All Enthusiasts” and “Save Your City” struck a chord with listeners who identified with their call for resistance. Their third album, Stealing of a Nation was released right before the 2004 elections and put down in many reviews as “too negative” for its honest view of the world. Their most recent full-length album Enemies Like This and new single “Packing Things Up on the Scene” show that they are experimenting with new sounds and subtler messages, but without backing down one bit. I had the chance to talk to front man Anthony Roman a few days before the group stopped by to play a show at DC’s Rock n’ Roll Hotel last month.

AB: What was the reason for Radio 4 getting together?

AR: Well, the idea was musical first. The idea was to try and play music that was rhythmic and had a danceable groove to it, some different things than what we had been hearing. We always write the music first, but once we started writing that, the idea of what to do lyrically came up. And, you know, it just seemed that more socially relevant lyrics fit the music better than maybe lyrics about personal issues. Also, we felt that ground was being covered. Because that whole indie rock thing was — even with artists that we really liked, like Elliot Smith — kind of down and introverted. And people like Beck and Pavement, they were maybe a bit too ironic for us. So, we wanted to do something that had something to say about the social climate in America.

AB: You mention the social climate in America in general, but have your songs also been about your own take on the situation in New York City in particular?

AR: To a certain extent they were. Once we started to leave New York, once we started to leave America and go tour and travel the world, we started to broaden our horizons with what we were writing about. But at the point of Gotham! we really had only done a couple tours, so I didn’t feel like we were very worldly. And there was a lot happening in New York at that point. We felt like New York was starting to change and really continues to change. And that’s something that we were not necessarily happy about. This is pre-9/11, we weren’t talking about anything to do with that. We were talking about what was happening internally with Giuliani and people like that. You know, we had always felt like people came to New York because it was artist-friendly, and people — whether they were musicians or filmmakers or painters or authors, whatever — they came to New York because they would see it as a very cultural place where you could create. We felt like . . . you know there was always this financial center, but it was becoming just about that. And we felt like it was losing some of its identity because of it. We’re fans of all the things that came to New York, whether it was the Velvet Underground, or Jim Jarmusch, or John Cassavetes, all those independent-spirited artists that made their way in New York. We felt like, “Hmm, could John Cassavetes or Jim Jarmusch come to New York now and have a loft and make films?”

AB: You mentioned Gotham! earlier, and that was my first exposure to you, so I want to come back to that. Another one of the things I have always liked about you guys is that you have this “indie rock,” “post-punk” base, but you also incorporate a lot of other styles into it like Afro-beat and reggae. Could you explain that a little bit more?

AR: Well, to begin with, it’s got to be something we are interested in musically. We can’t just do it because it’s “multicultural.” It’s got to be a type of music we like and enjoy playing and fits into what we do. Reggae and Afro-beat have always been big influences because they’re rhythmic and they’re repetitive and they’re political, and those are three things that I always look for in music. Dance music is also rhythmic and repetitive but it doesn’t say much lyrically. So those are the three types of music, outside of punk rock, I’m most excited about. And they all share that kind of revolving, repetitive beat with the vocal on top and groove of the bass line. I like that kind of thing. And whether it’s slow like in a reggae way or in a house way or an Afro-beat way, all those elements have figured into our music. But one of the things that always excited us about bands like the Talking Heads and The Clash was the fact that they would bring in these other elements and mix them in with these contemporary sounds like punk rock or rock music. I think that’s important because, one, it’s important to play different kinds of music. I would never want to be just a “ska band,” or a “punk band.” I want to be more than that. And, two, I think it’s important because it exposes people to music that maybe they wouldn’t be interested in otherwise. And I think some people like the DFA [record label] have enabled people to enjoy and understand dance music more than they ever would have without them. Somebody who writes for some kind of magazine or website maybe wouldn’t care about LCD Soundsystem‘s influences but certainly would pick up on what they’re doing. That’s a good thing about The Clash, or that’s why I like them anyway.

AB: The Gotham! album came out right after 9/11. How much of that was written before 9/11?

AR: All of it was written before 9/11.

AB: How did you find what the album had to say resonating with post-9/11 New York City?

AR: That was the thing. Some of the songs like “Save Your City” or “Start a Fire” all of a sudden had a different meaning. It was frightening to us, but I think what ended up on the record came out at the right time. And it all kind of connected for a lot of people. We were just being honest about what we felt; we didn’t know these events were going to take place the way they did. It’s a strange scenario, but the record became more important to us, and I think to other people, because it was talking about New York and the changes that needed to occur in New York.

AB: Was that the reason why Gotham! was the first album that gained you so much attention?

AR: It was that. I think it was timing, I think it was that people were starting to open up to danceable punk rock music being played again. The UK was very receptive to it, and that filters back into the States. It was a variety of things. I think The Strokes, for whatever people want to say, pro or con, opened the door for everyone. The door’s still open of course.

AB: My favorite song off the album, and you probably hear this a lot, is “Calling All Enthusiasts.” With the US driving to war right after 9/11, what did that song have to say that people needed to hear?

AR: It was a call to arms for people who were willing to resist. To put themselves in opposition. You know, “I’m really sorry but we need to start resisting,” that was the idea behind it. And I just felt like a lot of people were just going with the flow and being apathetic, and it was time to stand up and say, “Look, this isn’t working.” And that’s happened now, five years later, but it has happened. That’s the thing with movements or anything in America; whether you’re a rock band or a politician, to get the country to hear your message is probably one of the trickiest things you’ll ever do because of the sheer size of America. It’s really hard to make an impact, no matter what you’re doing. It’s much easier to go to, say, England and get everybody listening to you. That’s what I’ve found from music. So I think it takes a long time for the meaning of what you’re saying to get to people. I think they hear it a lot before they start paying attention to it. But it’s changed now, and it’s put us in a better place. And if it takes five years, or if it takes, whatever, twenty years, it takes what it takes. If the Democrats would have had some more charismatic leaders, it might have pushed things forward a little quicker. But, it is what it is.

AB: Now, after the release of Gotham! a lot of writers started comparing Radio 4 to other bands such as Gang of Four and especially The Clash because of your open politics. What do you say to those comparisons?

AR: Well, there’s not really much I can do about it. Stealing of a Nation in some bigger publications got criticized for being negative, and being a bit too blatantly political. The idea of The Clash is something that we’ve connected with, and if people compare us to that, then there’s really not much I can do about it. I wish they would less. But, you know, I guess it’s not the worst thing. It’s kind of weird with The Clash, because they were so successful that it’s almost like, if you do anything that’s reggae, then it’s like, “Okay you sound like The Clash.” If you do anything that’s political, it’s like, “Oh, they’re like The Clash.” If you do anything that’s punk, it’s like, “Oh, they’re like The Clash.” If you do anything that’s even starting to get into that funky kind of disco stuff, like they started to do later in their career, people say, “They sound like The Clash.” If you mix hip-hop into it, you get, “Oh, that’s like The Clash.” The Clash covered a lot of ground! Anything that almost anybody does can sound like them, especially if you come at it from a certain angle like we do where it’s political. I remember Rage Against The Machine was always getting compared to them, but these two bands sound nothing alike! It’s just the idea that they were political. People were saying, “Oh, they’re like The Clash.” Well, not really. It’s just that they have something to say. If someone’s acoustic and political, it’s like, “Oh, it’s acoustic Clash.” You know, everything kind of comes back to The Clash. So they’re a hard band to escape comparison to. Now, we’re not going to do something folky or psychedelic just to avoid Clash comparisons. But I do think it’s about how most music journalism is incredibly lazy. The decisions have been made beforehand. And, there’s not much you can do about that. A bad review, you can deal with it. When people turn things personal, that’s when we get kind of like, “Hmmm, well, I don’t know why they went there.” We’ve gotten really bad reviews and we’ve gotten really good reviews. I’ve seen both sides of it and it hasn’t really changed my life much. You’ve still got to do what you’ve got to do, and touring’s a drag, and America’s foreign policy still sucks. People almost think, “Ooh, you got a good review,” like my life is set. Or, “Oh, wow, you got a bad review,” well, let me go kill myself. No. One will make you smile for a few minutes and one will put you in a bad mood for a few minutes. Beyond that, it’s not really that big of a deal.

AB: You mentioned some of the laziness of a lot of music journalists. Do you think that the comparisons to The Clash come from an attempt to write off any political acts?

AR: Yeah. I think that there are certain publications that don’t have an interest in bands being political. But I think that there are a certain people who have just been waiting for indie rock to return. And there was a little period there around ’02 to ’04, when I felt like the music we were doing and those of our contemporaries were really kind of taking over the indie circuit. We were really making an impact. And now I feel like it’s returned back to this sound that we were reacting against. In a sense they won, because it’s back to this kind of mindset that just doesn’t do enough for me. If the movement’s just going to be about introspective songwriters, and journalists are just talking about their record collections and their reviews, and everything becomes so self-involved, then . . . I don’t know. That’s not what I want out of music, or a show, or anything. I think that there needs to be some sort of a connection between people. I mean, there’s a place for everything, but that’s just become the dominant thing. Like when I’m flipping through some of the indie-type shows, whether it’s [MTV indie music show] “Subterranean,” or there’s one called “New York Noise,” it’s almost like indie-rock is king again. But I find it really dull, to be honest with you, and it doesn’t have anything that I’m looking for. It doesn’t have enough of the spirit of say, punk rock. Punk rock wasn’t always supposed to be so self-involved. There was always this rhythmic thing and a connection between people. I don’t want them to jump up and down and beat each other up, but at least there was some type of movement. Because in a sense it’s a political statement; I was really excited when people were dancing at shows and now I just feel like it’s returned to . . . I don’t know.

AB: In between Gotham! and Stealing of a Nation your band released a lot of material. There was a live album, a handful of EP’s and singles. What was the reasoning behind this?

AR: The reason is that we had material! We just recorded over the summer and put out two new songs as B-side to our single. Whether it’s a remix or a new song, we’re always trying to put stuff out there. I mean, I always thought that if you’re a musician you’re supposed to make music! Actually, a lot of the stuff that came out between Gotham! and Nation was older stuff that was already sitting around. We were in a weird process: our first guitar player was starting to lose interest — that was a very unproductive period for us in a lot of ways. We kind of made it look like we were being productive. You know, if we sit in a room together, we can definitely create songs — that doesn’t take a whole lot of time. I believe in that tradition that a band will put out a record every year. I like that approach. But that’s also not just the fault of the bands, that’s also that fault of the record companies who want to you put out a record every two years and things like that. You can’t blame them for everything.

AB: Well, I remember I was living in London when Stealing of a Nation came out and there was a lot of promotion for that album.

AR: Yeah, there was this idea that it was going to be this “big album.” So the record company went to radio with two or three songs and when it didn’t really happen it was just sort of like, “Okay, we’re not really that kind of band.” I remember sitting in a restaurant in London, and they were like, “We went to radio with ‘Absolute Affirmation’ and ‘Party Crashers’ and neither one hit, so we’re not sure what we’re gonna do,” and we said, “What do you mean?” We were never the kind of band that got played on the radio. So what are we gonna do? We’re gonna go tour ’til we’re tired and we’re gonna go make another record. That has nothing to do with it. And we split from that record company after all that. Because it was obvious that they had spent so much money promoting the band that when things weren’t flying on the radio they were acting like, “Uh-oh, we better stop chasing this money by spending more money.” It was just one of those things that you get into that you don’t want to get into. Also the record wasn’t received really, really well. But, then again, some of our biggest successes have been from songs from that record, so it’s hard to say.

AB: Well, this was a record called Stealing of a Nation coming out right before the 2004 elections. Was that meant to be provocative in that sense?

AR: Yeah. We were just reading the paper in the studio and songs were coming out. We were very inspired by what was going on. And like I said, some people felt it was negative, and that annoyed them. We weren’t trying to be negative, we were just trying to be realistic.

AB: That negative label really does seem to come out of nowhere, because on every record I’ve listened to with you guys there is a refreshing element of positivism, as opposed to a lot of political bands that are very cynical. Why do you see a need for that?

AR: I always thought we were doing that, which is why when people were saying, “Oh, it’s so negative,” I was like, “Really?” And I would say this album [Enemies Like This] has a lot of positive things on it. I do think that there is a need to be hopeful. You’ve got to go through your day being hopeful. You know, a lot of the attitude was like, “I’m moving to Canada,” and things like that, and that’s not how you deal with things. You stay and you work it out. That’s what it seems like to me. That wouldn’t work for us.

AB: Enemies Like This, though still political, is much subtler, andhas a lot less sloganeering as you call it. What made you want to move in that direction?

AR: Well, we just felt that ground had already been covered. Seems to me it’s just as political as ever, though.

AB: Absolutely. Now that the album is recorded and you’ve been on tour with it, do you have any favorite songs off of it?

AR: I tend to like the stuff that sounds the least like things we’ve done in the past. “All in Control” is a little weird sounding to me, so I like that. I like “Everything’s in Question,” I like “The Grass Is Greener.” Just things that I think go in a different direction. The B-side that we just recorded for “Packing Things Up” is called “Pretty Good Lie,” and I’m really happy with how that came out. I think that’s one of the better Radio 4 songs. I tend to like things that sound the least like us, but I don’t know if that means they’re the best songs.

AB: You mentioned on the website that “All in Control” has this cool MIA-like beat to it.

AR: MIA’s someone I really like. She’s saying things, and she’s doing some interesting music.

AB: Was there a significance to releasing the most recent single (“Packing Things Up on the Scene”)?

AR: No. That was the record company’s choice. The video’s very political, though. I’m really happy about that. It seems to make a pretty interesting statement about things. Like I said, the b-sides I’m really happy with. The song’s been around for a while, so, to me, it’s just another song off the record. But I was really into the video and the B-side. It wasn’t a specific timing thing, like in the past where we’ve put out singles because we thought they should come out at a specific time. This just came out because the record company wanted us to do another single. There is a message to it. The idea behind it is: how could the youth of today look at the people who are supposed to be the leaders and have any sense of a moral foundation? Because corruption is so accepted that people can embezzle money and be back on TV in six months. Where do you find your role models? I guess that’s where the song goes.

AB: You just finished a tour of Europe. Did you notice any difference between the way people react to you over here and there?

AR: Well, we’ve been there so many times, so it’s not like anything that goes on over there is really anything new to us. But my wife came to Spain and France. And I think she was definitely surprised by the amount of energy and excitement people put into a show there, whereas they don’t really do that here. People don’t seem to get as excited about live music in the States as they do overseas. At least regarding our band. There’s a whole festival culture out there, where people will sleep out for a whole weekend just for music. That doesn’t really exist over here.

AB: With the most recent elections, people have obviously rejected the Bush agenda; the war, the corruption, the Bush version of a “prosperous economy.” People’s expectations have been raised. Do you see a role for political musicians to play in whatever social change may be coming?

AR: Well, I think a lot of musicians trying to open people’s eyes over the last couple years has helped. I think of people like Bruce Springsteen and what they did. And I always bring up Green Day. A lot of people make fun of Green Day, but they’re the band that’s getting through to twelve and fourteen year old kids. They’re the band that’s getting to people when they’re at an impressionable age and letting them know what’s wrong with this country. I feel like if musicians want to take on the responsibility then they should, but they shouldn’t feel like they need to. They’re not world leaders, they’re just people that write songs. And they have to write songs about what they want to write about.

Alexander Billet is a music journalist living in Washington DC. He runs the blog Rebel Frequencies, which can be viewed at rebelfrequencies.blogspot.com, and can be reached at [email protected]. For more information on Radio 4, visit their website: http://www.r4ny.com.

|

| Print