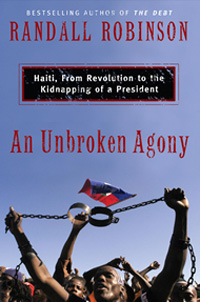

AN UNBROKEN AGONY: Haiti, From Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President by Randall Robinson BUY THIS BOOK |

Randall Robinson has written the story of a great tragedy of recent times — the violent overthrow of Haiti’s elected president and government on February 29, 2004. An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, From Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President gives a blow-by-blow account of the events surrounding that tragedy.

The author brings impressive credentials to the task. He helped to found the TransAfrica Forum, one of the most established human rights and social justice advocacy organizations in the U.S., dedicated to improving the lot of people of African descent. The Forum has long fought for a fair and respectful U.S. economic and political relationship with Haiti. His work gave him an enduring respect for the ousted president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, and his wife Mildred.

Robinson writes with an unapologetic passion for the Haitian people’s historic fight against slavery and colonialism. He situates the tragic events of 2004 on the broader canvas of the racism and imperial arrogance that has dominated the policies of the world’s big powers towards Haiti, particularly those of the U.S. and France.

Why is Haiti so poor, the uninformed observer will ask. Surely, after 200 years of nominal independence the country could do better?

“As punishment for creating the first free republic in the Americas (when thirteen percent of the people living in the United States were slaves),” Robinson replies, “The new Republic of Haiti was met with a global economic embargo imposed by the United States and Europe.”

“The Haitian economy has never recovered from the havoc France (and America) wreaked upon it, during and after slavery.”

Robinson is not trying to write a comprehensive history of Haiti. (Paul Farmer‘s The Uses of Haiti fits that bill admirably.) He does, however, provide enough historical background to explain the present-day.

The author rushes the reader back and forth in time and place in an effort to recreate the drama and tragedy of February 2004. “It was Friday, February 27, 2004,” he opens one chapter, “the evening before the last day of Haitian democracy.”

The stage for the overthrow of February 29, 2004 was set in the national election in the year 2000. Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected president for a second time. The U.S., France, and Canada, the three contemporary overseers of Haiti, threw up their hands in exasperation over the electorate’s choice of a man and a political movement dedicated to lifting the burden of their crushing poverty.

Aristide promised improvements to the lot of the desperately poor Haitian majority, and he was a man of his word. The big powers would have none of it. They began an embargo of aid funds to the government, directing funds instead to parallel services operated by “non-governmental” or charitable organizations. Soon they would also block the government’s requests to international financial institutions for loans to finance ambitious education and health care projects

More ominously, money and arms flowed to paramilitary forces sponsored by the venal Haitian elite and drawn from the disbanded Haitian army or purged Haitian National Police. The paramilitaries were safely lodged in the neighboring Dominican Republic. Robinson captures the gravity and drama of the periodic assaults they launched against the institutions of the Haitian government following the 2000 election.

When the paramilitaries launched what became a final incursion in early 2004, they were a small force, no more than 200. They were feared and hated by the majority of the Haitian people. By virtue of an overwhelming superiority of arms, they were able to wreck government rule in cities in the north of the country. But they didn’t have a chance of taking the capital city. That task fell to their international sponsors, and this was done on February 28-29. The U.S., France, Canada, and Chile landed troops at strategic locations in the country.

The Aristides were taken by U.S military forces to one of the most isolated countries in the world, the Central African Republic. An Unbroken Agony kicks into high gear as the author tells the story of the delegation he led on a harrowing flight to the Central African Republic on March 14 to rescue them from a quasi-imprisonment. The delegation included U.S. congresswoman Maxine Walters. It had no idea of the reception it would receive from the country’s ruler, François Bozize, a client of French imperialism. After many tense hours, Bozize gave permission to the delegation to leave, its mission accomplished. The Aristides were granted political exile in South Africa, where they remain to this day.

One of the myths perpetrated by supporters of the foreign intervention in Haiti is that Jean-Bertrand Aristide was prepared to leave the presidency and the country in the face of the mounting political pressure against him. The Aristides accepted a U.S. offer to whisk them out of the country, so the story goes. Robinson presents extensive documentation to dispel the myth.

An Unbroken Agony prompted many questions in the mind of this reader. How did the paramilitaries achieve such a devastating impact? The Haitians who overthrew Haitian democracy in February 2004 were a tiny force — their principal leader, Guy Philippe, received less than two percent of the vote in the 2006 presidential election. Were there more decisive steps that the Aristide government could have taken to defend the country and minimize the havoc they caused following the 2000 election?

And what has become of Latin American solidarity? Robinson describes the selfless measures of the early 19th-century Haitian revolutionaries to aid the independence struggle of the South American peoples led by Simón Bolivar. Today, the majority of the 7,100 foot soldiers of the post-2004 UN-sponsored occupation force in Haiti are drawn from the countries of Latin America, with Brazil — whose president is the leader of the governing “Workers Party” — in the lead. The UN force is responsible for innumerable killings and jailings of pro-democracy fighters following February 2004. Thankfully, substantial aid and solidarity to Haiti from Venezuela and Cuba keeps the banner of Simón Bolivar flying high in Haiti.

Haiti is living an unprecedented economic and social calamity as a consequence of the coup d’etat of 2004. The violent overthrow of its government received little attention or concern from democratic opinion in the world. A shameful silence still reigns.

Roger Annis travelled to Haiti from August 5 to 20 as a participant in a human rights investigative delegation. He can be reached at [email protected]. You can read his reports from Haiti at www.thac.ca/blog/9.

|

| Print