Is there anyone with a deeper knowledge of the contemporary American labor movement than Kim Moody? He not only seems familiar with the strategies and outcomes of practically every strike and organizing drive of the last twenty years. He also appears to know the status of each union local, large and small, as well as every workers’ center. If he says that a national union is largely bureaucratized and timid, he is also quick to mention the two or three locals that are exceptions to the rule.

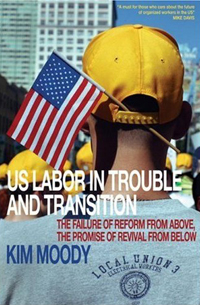

Moody draws on this vast knowledge in his new book, US Labor in Trouble and Transition: The Failure of Reform from Above, the Promise of Rebellion from Below. The text focuses on the course of working-class struggle over the last twenty-five years in the US, not exactly an inspiring time filled with bold movements and major victories. Nevertheless, the picture is not altogether without hope or bright spots. The book should be crucial reading for those concerned with rebuilding the Left, because a powerful union movement is important to such an effort. Precisely how important is a matter of some debate, which I will touch on below.

Moody draws on this vast knowledge in his new book, US Labor in Trouble and Transition: The Failure of Reform from Above, the Promise of Rebellion from Below. The text focuses on the course of working-class struggle over the last twenty-five years in the US, not exactly an inspiring time filled with bold movements and major victories. Nevertheless, the picture is not altogether without hope or bright spots. The book should be crucial reading for those concerned with rebuilding the Left, because a powerful union movement is important to such an effort. Precisely how important is a matter of some debate, which I will touch on below.

Moody begins by outlining changes to the US economy in the last couple of decades. His take on this question is different than most on the Left. Although there has been a shift to more employment in services, industry has not left the US, for the most part. Rather, the industrial union bastions of the Midwest have been weakened mainly by two trends internal to the US. Corporations have employed technology to reduce the size of the industrial workforce, without necessarily reducing its output. And corporations have often moved industry to anti-union regions of the US, most notably the South. At one point he writes that unions complain of jobs moving overseas when in fact they have moved down the interstate. He does not altogether discount that some jobs have moved overseas, of course. But he also notes, as is often absent from these discussions in the US, that the process cuts the other way as well. Many foreign car companies have opened plants in the US, mostly in the South. Also significant has been the trend towards corporate mergers and acquisitions. This shifted over time from simple financial grabs to strategic purchases of competitors, in the process often weakening unions. For example, unionized UPS purchased non-union Overnite (which became UPS Freight).

Moody doggedly emphasizes the centrality of certain ‘traditional’ industrial workforces in the US, in, for example, meatpacking, auto, and transportation. I don’t think the words “dot com” appear in the text, and he is indifferent to the vogue on some parts of the left for organizing “knowledge workers” (i.e. grad students) or “sex workers” (strippers, prostitutes). As I read the book, I couldn’t help but wonder if the indifference on much of the left to industrial workers, notwithstanding their continued economic salience, has as much to do with class bias as to any dramatic shifts in the nature of capitalism.

The geographical shift in manufacturing to non-unionized parts of the country and the technological shift to a smaller, more productive workforce might not have been so devastating to the fortunes of US labor if it had not been for the ‘business unionism’ orientation of most of the labor leadership. In this view, unions are best off working closely with business, trusting that “what’s good for General Motors” will ultimately benefit their membership. There is a broad logical problem with this orientation –business and labor are both struggling to maximize their chunk of surplus value, so their interests are fundamentally in conflict — and there is also a political and historical problem. Since the 1970s, when profit rates fell, business has become much more aggressive about pursuing an anti-union agenda, both politically and in the workplace. The unions, with a leadership that has failed to absorb the implications of this, have been disarmed and ineffective in the face of the onslaught. Although successful strikes have occurred, by employing such tactics as broadly disrupting the function of a metropolitan area (Pittston in 1989) or mobilizing the grassroots of a national union (UPS in 1996), the union leadership has not sought to generalize these tactics.

Additionally, Moody faults the unions for their embrace of the Democratic Party. Since the late forties, this has brought at best limited gains. In a first period, until the mid sixties, a considerable chunk of the party represented whites in the segregated South and was unsympathetic to an expansion of union-backed social demands. When this group mostly left the Democrats after the passage of civil rights legislation, the party increasingly became the terrain for relatively wealthy liberals detached from the working class. Lip service to union hopes was barely being paid by the time the Clinton administration joined with the Republicans to push through NAFTA. The union response has been neither to move towards building a third party (the strategy Moody aligns himself with) nor towards developing a strategy which might push the Democrats to the Left through grassroots pressure. Instead, “reform from above” efforts (first through the election of John Sweeney to leadership of the AFL-CIO, then through the fracturing of the federation with the emergence of the Change to Win coalition led by Sweeney protégé Andy Stern) have focused on revitalizing organizing drives to expand membership, while political initiatives have largely settled for trying to elect more Democrats, whatever their politics. Additionally, there has been a wave of mergers and consolidations of unions. These reform efforts have not been successful in increasing union density or power, embedded as they are in an expansive union bureaucracy staffed by professionals rather than the creation of a working-class cadre who can both articulate the need for unions and develop workplace-based strategies of struggle. Indeed, Stern, while opening up SEIU to some of the activists who emerged in the seventies and enjoying some success at organizing more workers into SEIU, goes even further than the traditional business union model, adopting an approach to union organization modeled on corporate America (and dismissive of union democracy) and strategies of “partnership” with employers that deeply compromise goals of working class solidarity. Furthermore, some other unions have altogether abandoned any concept of solidarity in favor of endorsing any politician, including Republicans, who can promise them progress on short-term demands.

The picture is not entirely hopeless. Moody calls attention to the expansion of workers’ centers, which typically focus on unorganized workers, reform caucuses which focus on democratizing unions, and the immigrants rights movement which has combined political struggle with workplace action (such as the work stoppage on May 1, 2006). He also highlights the activity of “non-majority” unions, which, while failing to win unionized status for an entire workplace, nevertheless hang in and continue to fight for their members. In a final chapter devoted to strategy, Moody emphasizes the potential of organizing in the South, particularly in major industries such as meatpacking and auto. He suggests that a more powerful union movement in the South will be necessary before Wal-Mart can effectively be confronted. He also calls for more democratic and militant unions and alliances with community groups. Regarding the latter, he believes that unions bring power to the community groups (citing Brazilian and South African examples), more than vice versa. Unions should also develop international ties to combat neoliberalism and empire. Finally, he advocates for third-party action, to break with the Democrats and offer a more substantially pro-working class agenda. Moody himself was involved with the forming of a US Labor Party, which he concedes has not been particularly effective.

This is a valuable book, and I strongly recommend that anyone concerned with the future of the Left in the US read it. Its emphasis on the industrial working class provides a bracing alternative to much contemporary radical theory, which finds various excuses to forget about them. In general, even the most politically left websites provide minimal coverage of the labor movement, although it is difficult to see how the Left can rebuild itself in the US without engaging this question. This book is a superb place to start.

If there is a problem with it, it is what I would call Moody’s “laborism.” That the industrial working class is strategically positioned to disrupt the capitalist economy is difficult to dispute. But this is a separate question from the roots of a politically radical program. A few examples might help clarify this point. First, none of the three radical electoral governments in South America — Venezuela, Ecuador, and Bolivia — ascended through insurgency of industrial workers. Instead, other groups, including indigenous people, slum dwellers, and reform officers movements have successfully allied to create majority electoral coalitions. Not only in the US, but in many different countries, industrial unions have entered into knotty alliances with center-left parties that simultaneously consolidate some limited gains while rendering further offensives more difficult. The cases of Brazil and South Africa are relevant in this respect. In neither is the role of leading social movement challenging a neoliberal, center-left regime being played by industrial unions. In Brazil, this position is staked out by the landless movement, while in South Africa it is “the poor,” rooted in the slums, who have moved towards a more confrontational stance. Radicalism is born not only of exploitation but also of political contradictions and deprivation. Often trade unions, precisely by virtue of their power, can make a deal with employers that is good enough, at least for a time, for their members, and their radical edge is blunted. Of course, the Left has been struggling with these questions since the time of Lenin.

In the US, the question of where a new radicalism might be grounded has to consider the historical role of African Americans. The Jeremiah Wright flap is just the latest evidence that this community provides the only mass basis in the US for an anti-imperialist, left-social-democratic message (contrast Wright’s rhetoric about the US role in the world with what emanates from the labor movement about trade. In the latter, the US, the strongest state in the world, is typically portrayed as the victim at the hands of countries like China). While Moody brings up racism from time to time, this question is largely absent from the final chapter on strategy. It is worth noting that many of the struggles he writes approvingly of here in North Carolina (with the notable exception of Farm Workers, overwhelmingly immigrants) are led by African Americans. Meanwhile, under progressive leadership, the state NAACP has pulled together a coalition of social movements to struggle around a social democratic and anti-intervention platform. In North Carolina, as in much of the South, it is difficult to conceive of any union or coalition of unions playing this role. Although it is not a party (and third parties are an extremely tough sell in the US, given the winner-take-all nature of elections), the rallies of this movement are notable for the reduced role played by elected officials or candidates. African Americans not only face the brutal conditions in workplaces described by Moody, but, more directly than most white workers, confront the ruinous effects in schools, prisons, and their neighborhoods of neoliberal and imperial policies. Furthermore, there is a deep tradition of struggle to build on. A revitalized militancy among labor unions will have to align itself closely with the aspirations of this community if it is to have any teeth as part of a broader movement for change in the US.

Steven Sherman maintains the website lefteyeonbooks.org. He can be reached at [email protected].

|

| Print