Until the early 1980s, homes in the US were mostly owned by the families living in them. By 2008, all that changed. Now US homes are actually owned — about 60% of the average home — by mortgage lenders. The families in them own the other 40% of the home’s value. The average US home “owner” actually owns less of his/her home than the mortgage lenders do. Home “owners” have become more like renters: owning ever less of their homes, they can remain only so long as they pay monthly to the lenders who own ever more.

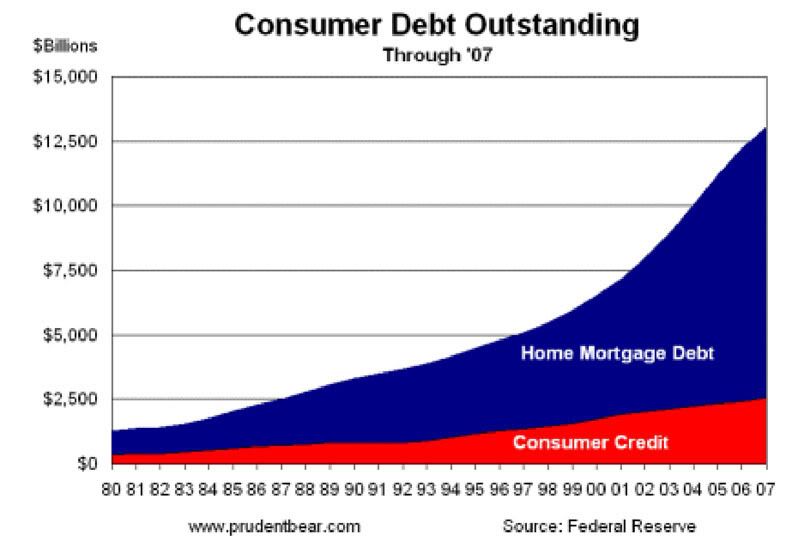

In the 1960s and 1970s, homes were like investments into which workers poured their fix-it labor, their free time, and what money they could save from their wages. But in the late 1970s, workers’ average real wages (money wages adjusted for the prices of commodities that workers buy) stopped rising. Before, from 1820 to 1970, real wages rose every decade. That made possible the steadily rising standard of consumption that compensated workers for their ever rising productivity and the strains of ever harder, faster labor. But since the mid-1970s, stagnant real wages for US workers threatened the rising levels of consumption that they had come to expect as their American birthright and the measure of their personal worth and success. To consume more, workers had to borrow, and borrow they surely did as the graph below shows.

They borrowed and gave their homes as collateral to the lenders. Home mortgage debt is the total money borrowed by US homeowners and secured by the lender’s right to take the home via “foreclosure” if the owner does not pay the loans back with interest every month. Consumer credit is chiefly credit card debt also built up by workers, especially since the early 1990s.

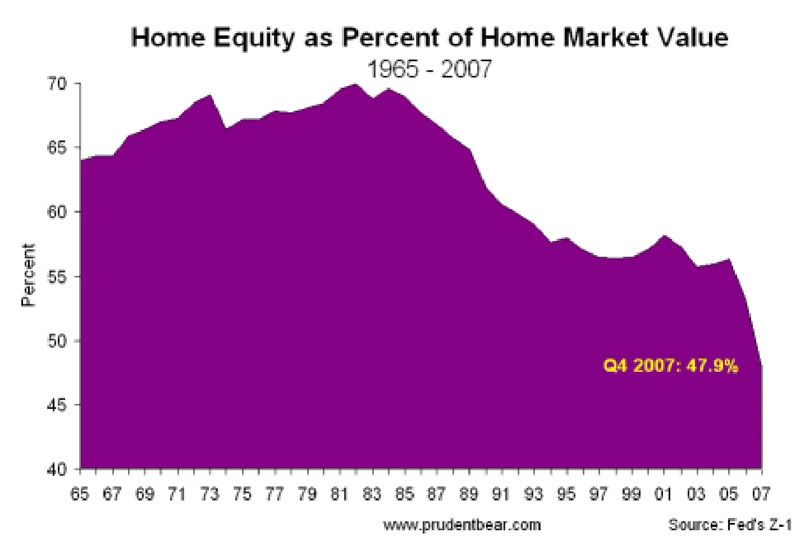

The graph below shows what portion of US homes was actually owned by families, their “home equity.” In the 1960s and 1970s, Americans owned about two thirds of the market values of their homes. Then, just when real wages stopped rising, home equity started falling. From the early 1980s to 2006, families borrowed ever more so that their home equity fell as a percentage of the home’s value. The fall in the home equity percentage was cushioned then by the fact that home prices rose to 2006. While mortgage borrowing reduced families’ home equity, the rising home prices raised home equity. From the early 1980s to 2006, mortgage borrowing simply rose faster than home prices. However, when home prices stopped rising and began the fall that is still underway, the home equity portion of US homes plunged downward as the graph shows.

The end of rising real wages in the US drove workers to keep consuming by using up the only wealth accumulated by the home-owners among them. As they borrowed, they lost their home equity. Now, as stagnant wages, rising unemployment, and rising prices take their tolls, Americans by the millions are losing their homes. Those able to keep their homes have dwindling home equity and consequently dwindling capacity to borrow. All workers will spend less, so stores will sell less, so producing companies will lay off other workers: there’s no point in producing what you cannot sell. Laid-off workers will then cut back their spending and reinforce the economic decline. We are in that typical downward spiral that economists eventually call recession or, if it gets bad enough and/or lasts long enough, depression.

And that indeed is where we stand in the summer of 2008 amid the vanishing American dream. But if this prospect is troubling, one way to avoid worrying is to listen to the spokespersons of the US government or indeed most politicians and big business folks: they see a turning point, they are looking up, they seem sure the worst is behind us, they celebrate the greatness of free enterprise, and so on. Fires always seem to bring out fiddlers.

By way of conclusion, consider a speech given by a political leader when the economic crisis was already in full bloom last September. This quotation today opens this candidate’s website devoted to economic issues:

“I believe that America’s free market has been the engine of America’s great progress. It’s created a prosperity that is the envy of the world. It’s led to a standard of living unmatched in history. And it has provided great rewards to the innovators and risk-takers who have made America a beacon for science, and technology, and discovery. . . . We are all in this together. From CEOs to shareholders, from financiers to factory workers, we all have a stake in each other’s success because the more Americans prosper, the more America prospers.”

— Barack Obama, New York, NY, September 17, 2007

Rick Wolff is Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is the author of many books and articles, including (with Stephen Resnick) Class Theory and History: Capitalism and Communism in the U.S.S.R. (Routledge, 2002) and (with Stephen Resnick) New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006).

Rick Wolff is Professor of Economics at University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is the author of many books and articles, including (with Stephen Resnick) Class Theory and History: Capitalism and Communism in the U.S.S.R. (Routledge, 2002) and (with Stephen Resnick) New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006).

|

| Print