I don’t want to serve. . . . I think that in fighting in the cinema, through our movies, for a freer, more authentic expression, with weapons that can include joie de vivre and comedy, we are waging the same war as those who fight on the barricades. — Dušan Makavejev (1971)

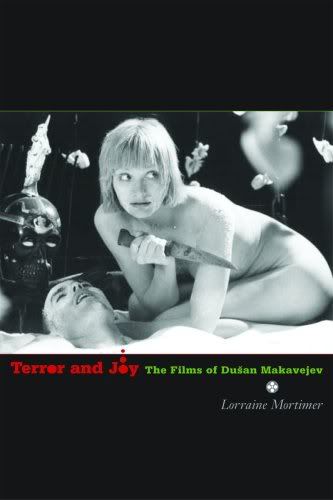

Infamous Yugoslavian film maker Dušan Makavejev was the person responsible for a sequence of highly challenging, inventive and provocative films including the cult classics W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) and Sweet Movie (1974), as well as lesser known films such as Man Is Not a Bird (1965) and Love Affair; Or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (1967). Here, for the first time as far as I am aware, we have an extensive English language appraisal of his films in the form of Terror and Joy: The Films of Dušan Makavejev by Lorraine Mortimer. An impossible task some might think, especially when one recalls Sweet Movie with its inclusion of primal regression footage shot at Otto Muehl’s AA-Commune, its playful and satiric view of left politics, its literally seductive scenarios and the use of documentary footage of the unearthing of the victims of the 1943 Katyn massacre. The affective force and bodily resonance of his films seem to make the encapsulating power of language impotent. As viewers, then, we are confronted by paradoxical, ambivalence-inducing films, a kind of mélange of formal richness and coruscating content, that can be deeply discomforting. This unease, I feel, would be heightened in those viewers (like myself when I first saw Sweet Movie) who would expect some recognisable auteurial directiveness or central protagonist to be embedded in the films as a guide to their possible interpretation or potential enaction. So, W.R., or World Revolution/Wilhelm Reich promises answers, a way forward be it of a leftist or psycho-sexual nature, but we don’t get this. We get a kind of immersion in the experiential material and through this are being exposed to what Makavejev has called ‘shifting gestalts’ (p.176). We’re are asked to be more than spectators, to do more than be lead by our projective identifications.

Infamous Yugoslavian film maker Dušan Makavejev was the person responsible for a sequence of highly challenging, inventive and provocative films including the cult classics W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) and Sweet Movie (1974), as well as lesser known films such as Man Is Not a Bird (1965) and Love Affair; Or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (1967). Here, for the first time as far as I am aware, we have an extensive English language appraisal of his films in the form of Terror and Joy: The Films of Dušan Makavejev by Lorraine Mortimer. An impossible task some might think, especially when one recalls Sweet Movie with its inclusion of primal regression footage shot at Otto Muehl’s AA-Commune, its playful and satiric view of left politics, its literally seductive scenarios and the use of documentary footage of the unearthing of the victims of the 1943 Katyn massacre. The affective force and bodily resonance of his films seem to make the encapsulating power of language impotent. As viewers, then, we are confronted by paradoxical, ambivalence-inducing films, a kind of mélange of formal richness and coruscating content, that can be deeply discomforting. This unease, I feel, would be heightened in those viewers (like myself when I first saw Sweet Movie) who would expect some recognisable auteurial directiveness or central protagonist to be embedded in the films as a guide to their possible interpretation or potential enaction. So, W.R., or World Revolution/Wilhelm Reich promises answers, a way forward be it of a leftist or psycho-sexual nature, but we don’t get this. We get a kind of immersion in the experiential material and through this are being exposed to what Makavejev has called ‘shifting gestalts’ (p.176). We’re are asked to be more than spectators, to do more than be lead by our projective identifications.

So, this discomfort comes, in part, from Makavejev’s refusal to give us any firm ideological anchoring (we expect a new vision of leftism) whilst at the same time providing us with something far more populist and genuinely entertaining than a distanciated Godard could ever dream of. Like Anna Planeta’s seduction of the young boys in Sweet Movie we too, as viewers, are seduced by something beyond our ken; especially if we expect an authorial vision as a unifying factor. His early films, then, are, to re-coin a phrase, ‘difficult fun’. In many ways they abandon conventional narrative storytelling for what more than one commentator has described as ‘associative montage’. This more poetic approach to cinema with its intense awareness of what is being re-presented or juxtaposed, be it documentary footage or, in the case of Innocence Unprotected (1968), a whole film by an amateur film-maker from 1944, not only makes us reconsider the oft touted practice of detournement (through which often unconscious aspects of the re-presented text muddy or infect the ‘message’) but, as Lorraine Mortimer paraphrases Makavejev, such a poetical approach ‘has more to do with our desires, with their ability to connect us with our unreal self’ (p.120). Such a proffered connection is also facilitated by the fact that there is not one central protagonist in his early films. In the words of Augusto Boal, the ‘prosthesis of desire’ that marries spectator to protagonist, that ‘prosthetically implants in the spectator, the desires of the protagonist’ is liberatingly absent.1 We have instead a diffuse and wandering desire that may lead us to our ‘unreal self’, a self distant from the ideal or ideologised version of ourselves that the reductive trickery of central protagonists often instil or re-instil or make us reactively fall back upon.

That these desires and ‘unreal selves’ are often, in part, produced in us and are not by any means ‘pure’ and ‘progressive’, is a further reason for the entertaining complexity of Makavejev’s films of this period. Having to some degree got beyond the socialistic propaganda for a ‘New Man’, having been subjected to it and, indeed, subjectified by it since his youth, he nevertheless doesn’t ‘lord it over’ such produced subjects, but seems to nonjudgementally honour their human striving and stumblings. Consistently wielding his own life history, and an attendant auto-ironic commentary, Makavejev is thus not cruel to his characters, he doesn’t use them as ideological ciphers or scapegoats. He seems to be saying that we are all victims of ideology in one form or another and this is just as applicable to what he seemingly presents as radical and progressive: the ideas of Wilhelm Reich, the ‘degree zero’ of primal regression, the militant sincerity of party members, the ‘free state’ of the Red commune-barge with its cartoonesque Marx figurehead. As he put it: ‘I wanted to show how people are permeated by ideologies and how their conduct, gestures, opinions, thoughts, are unconsciously influenced by ideological hypnosis‘ (p.79).

This may account for why, along with much cinema from Central and Eastern Europe of this time, there is, to borrow from a recent article by Negri, a ‘reappropriation of a common reality‘.2 In other words Makavejev and others are exploring ‘everyday life’ before it has been theorised as a category. They wield the common life, a life of banality, of love-striving and relational depth, a life of reproductive labour as a counterpoint or subversion of the state-communist model of what it means to be a satisfied worker, a productive human being. A struggle at the level of the production of the subject but one which, subsisting beneath character armour, profiles the poetics of unbared lives. As Bataille has described it ‘if poetry introduces the strange it does so by means of the familiar‘.3 One example amidst many is the scene in Love Affair when an East German workers’ song played on the gramophone of a party member provides the soundtrack to Isabella as she cradles a washing basket on her hip and glides through the stairwells and courtyard of the tenement building in which they live.

These strands of ‘ideological critique’, of the abandonment of the ‘prosthesis of desire’ and the shifting non-didactics of Makavejev as an editor-director, may go towards explaining why Makavejev’s films are often referred to as a ‘cinema of ideas’ or as ‘intellectual cinema’. This seems to be a constant claim made by commentators on Makavejev. Not only does it fit the bill of enabling the film studies operation to locate him in a cinematic lineage going back to Eisenstein and Vertov (film-makers that Makavejev has mentioned in several interviews and who practically theorised such a cinema), it may also attest to a different kind of intellectuality at play, one for whom affect and concept are more intimately entwined in a poetical form of expression and intent.4 The complexity of his films, then, is not just in the associative montage itself, his mixing of fiction and documentary, of rehearsed and improvised scenes, the associative leaps (or as the Surrealists would say, the ‘point sublime’), it may also be about how the viewers of his films, abandoned by the familiarity of protagonists and unmoored from surrogate desire, are having to redress their mode of watching (‘I have been fighting narrative for years’ said Makavejev).

So, in the absence of direct, linear narrative, or even an atemporal presentation of the story, we have, as Makavejev said of Innocence Unprotected, a cultural experience in which ‘the film is fiction at one moment, a document at another’ and that the viewer has to ‘re-tune himself‘ (p.133). The ‘intellectual’ aspect is, then, something more sensual and visceral than we are normally used to: not just in the famous moulded penis scene of W.R. or in the open-air embrace between Ana Planeta and Luv Bakunin in Sweet Movie, but in the way that our will to perceive, being shown sometimes what it doesn’t want to see, becomes desirous of escape from readymade categories for that perception.5 Straight narrative and straight documentary can become prisons for the wandering prismatics of desire. As Makavejev goes on to say ‘the borders fade . . . there is a lot of present in the past and something from the past that still lasts . . . reality is full of illusions and documents full of fictitiousness’ (p.133). Is there, then, not a meeting between our will to perceive differently and the power of the poetic image? Is it not that affective energy can be endowed with causal power? When Isabel makes apple strudel in Love Affair she blows under a thin skein of pastry laid out on a table and it becomes a libidinal skin literally rising from the table and giving three dimensional movement to those tingling sensations we have all felt.

That an image such as this could be followed by documentary footage of a morgued-corpse or a scene from a Soviet film depicting the dismantling of a church may well locate Makavejev’s films in the realm of an imbrication of Eros and Thanatos, of art house and B Movie, of tract and poem, of personal power and voluntary servitude. As he has said of W.R. ‘to film an idea is not to congeal it in some didactic exposé that can only turn away the very people we aim to address . . . it is to assemble the most disparate elements . . . then to balance it in an unstable equilibrium.’ (p.174). Whilst this may not apply to all of Makavejev’s films (I have not seen the later ones) there is this quality in his early work that brings differences into an uneasy collision, an uneasy truce that strives to create newer social relationships between people and objects that can figure as ‘becomings’ against the odds. In Love Affair there is the relationship between a Hungarian woman and a Muslim Slav, between a switchboard operator and a rat catcher, between white collar and blue collar, between a shopper and a communist; there is the dry scientific lectures of a sexologist and criminologist juxtaposed against an accidental crime of despair emanating from the embers of betrayed passion; there is the constant chatter of the phone lines set against a silent image of Isabella blowing a soap bubble emptied of speech.

Makavejev, then, seems to be offering, as does Milos Foreman in his early films, that it is a political facet of daily life to have a frisson of differences rather than their being subdued in homogeneous and molar ‘repressing representations’. Makavejev enigmatises (or should I say ‘realistically portrays’) this further by having these frissons run through his part-protagonists. In W.R., Milena in her nightie dons an army jacket and forage-cap (symbols in this context of the struggle of the partisans?) before delivering her far from ‘coherent’ speech that centres, in a Reichian Sexpol mode, on workers’ liberation of their desires: ‘That’s why we go for politics, because our orgasm is incomplete‘. As Mortimer adds, without commenting upon the wider applicability of our internal antagonisms and their social sources: ‘The paradox of her slightly fascist, charismatic bearing and her anti-fascist free-love, self management message is always at the fore’ (p.164). Maybe it’s not so much of a paradox for a produced subject to be carrying none too pure introjected impulses, to be overdetermined by self doubt and to thereby attempt to appear sturdily identified? Maybe it’s not too paradoxical to be stumbling towards an inspirational articulation by means of inbred modes of expression?

With working class characters respected and almost honoured yet with working class ideology put forth as an oppressive fairy tale, this play of difference at the level of content (everyday life v its official version), at the level of form (idiomatic elisions) and at the level of individual characters (congruent ambivalence) gives rise, in these early films of Makavejev as well as those of others, to the political potential of singularities as the breach point in the representational politics of the mass individual.6 This political or anti-political tenor to Makavejev’s films is one that gives them an import that seems to surpass their reception as ‘cinema’. That such a tenor to his films is only dimly apprehended by Mortimer is a case in point and one that tarnishes Terror and Joy for me. For, like so many of the points made in this book (that seems to have been constructed as a ‘patchwork’ of quotes that have been too tightly stitched), those that take us on conjectural flights always seem to come from one of the myriad of quotes that she assembles here. So, it is left to Yvette Biró to draw out that aspect of Makavejev’s work that counters the ‘repressing representation’ of mass individuality: ‘As opposed to the more lifeless category of abstract differentiation, it [Love Affair] gives us the uniqueness and unalterable concreteness of all lifelike traits, and the incomparability of every realised quality‘ (p.105). So, for me Biró seems to be suggesting that Makavejev (in a manner not dissimilar to Pasolini’s early films7) is, in his early movies at least, using an everyday, unadulterated reality to put the power of singularities into dramatic tension with the mythic-narrational channelling of desire by means of ‘abstract differentiation’ (i.e. working class ideology or the ideology of consumerism etc.).

There are many such cues and avenues in Makavejev’s films but they are not followed-up by Mortimer who seems engaged in that peculiarly persistent operation of academic cultural capture which sees the presentation of the facts as initially necessary before any more conjectural or poetic examination of the facts can proceed.8 In line with this one could similarly offer that Mortimer’s book, functioning too much as a ‘case for the defence’, is shoehorning Makavejev into the discipline of film studies and, remembering Augusto Boal, there is, with the author functioning as the protagonist, a ‘prosthetics of desire’ at play in Terror and Joy too. The accumulation of facts and quotations may be indicative of exhaustive research, but it has the effect of over academicising Makavejev, making his films follow the gridlock format of a written apprehension. It’s as if some sort of court of law is in session somewhere that adjudges Makavejev’s work too unarty, too free love, too political, too funny, too uncommitted.

An effect of this approach is not only that the footnotes are collected in a chapter size chunk at the back, but that very early on in the book we begin to doubt whether Mortimer has anything unbarrister-like to say. Reliant on the sanctioned, external locus of evaluation of various essayists, interviewers and Makavejev himself, on the authority of what has passed before, she seems here to be collecting it together in a bid to facilitate Makavejev’s entry into the Anglo-speaking canon. This all adds up to the stable equilibrium of a narrowing of perception. Our desires become mediated by a language that we thought would fail marvellously. It’s as if some of the larger questions posed by Makavejev have been unheeded. . . .

Will man be remade

Will the new man preserve. . .

. . .certain old organs?

— Dušan Makavejev, intertitle, Love Affair; Or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator

Footnotes

1 Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed, London: Pluto 2000. p.xviii.

2 Antonio Negri, ‘Communism: Some Thoughts on the Concept and Practice’, 14/3/2009.

3 Georges Bataille, Inner Experience, New York: Suny 1988 p.5.

4 In a December 2000 interview with Ray Privett he also mentions the ribald films of Russ Mayer and one particular short porno flick disguised as an educational film that he saw at a film festival in Oberhausen, Germany. See Ray Privett, ‘The Country of Movies: An Interview with Dušan Makavejev’, <archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/11/makavejev.html>.

5 See for instance the final shots of Sweet Movie when supposedly dead children begin to rise from underneath forensic sheeting.

6 For a recent articulation of this approach see Bifo at <www.generation-online.org/p/fp_bifo6.htm>.

7 Maybe there was more than a distant kinship between the two as Pasolini was an involved supporter of the much censured Sweet Movie. Makavejev in conversation to Ray Privett: ‘The Italian version was made by Pier Paolo Pasolini. He chose the voices for the dubbing. And he participated also after it was immediately banned. . . . Pasolini had written a letter to the judge and made a public statement.’ See Privett, op. cit.

8 This is not the case with Raymond Durgnat’s book on W.R. which is pacey and not shy of formal experiments. See for example the chapter entitled ‘Appreciations’ in Raymond Durgnat, W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism, London: BFI Screen Classics, 1999.

Howard Slater is a trainee counsellor and sometime writer living in East London. This article was first published by Mute Magazine on 9 September 2009; it is reproduced here for non-profit educational purposes.