Mixing Different Things

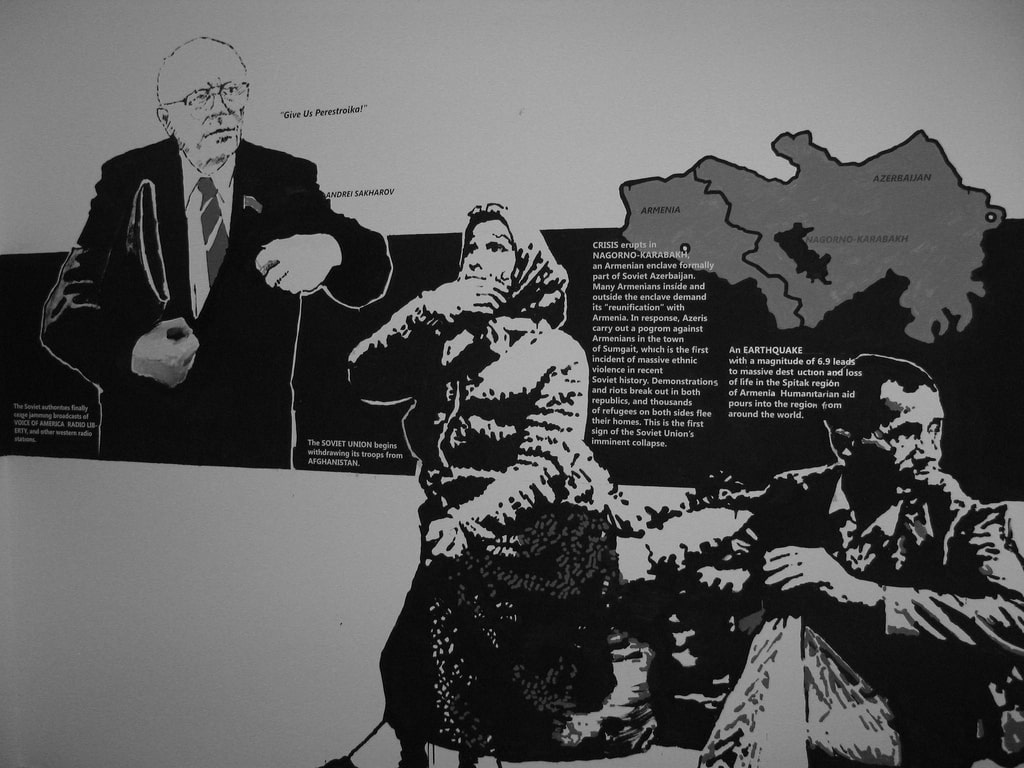

“Perestroika,” Graphic and Video Installation, 11th International Istanbul Biennial, 2009 |

The editorial and exhibition policy of Chto Delat is often accused of inconsistency, of lacking a clear “party line.” What is important for us today is to arrive at a method that would enable us to mix quite different things — reactionary form and radical content, anarchic spontaneity and organizational discipline, hedonism and asceticism, etc. It is a matter of finding the right proportions. That is, we are once again forced to solve the old problems of composition while also not forgetting that the most faithful composition is always built on the simultaneous sublation and supercharging of contradictions. As Master Bertolt taught us, these contradictions should be resolved not in the work of art, but in real life.

On the Usefulness of Declarations

Everyone has long ago given up wracking their brains over the question of whether it is possible to elaborate precise rules for organizing the work of a collective. It is now quite rare to come across a new manifesto or declaration. The cult of spontaneity, reactivity, and tactics — the rejection of readymade rules — is the order of the day. Tactics, however, is something less than method. Only by uniting tactics and strategy can we arrive at method. Hence it is a good thing to try one’s hand at writing manifestos from time to time.

On the Totality of Capital, or Playing the Idiot

Today it is all the rage to say that there is nothing outside the contemporary world order. Capital and market relations are total, and even if someone or something escapes this logic, then this does not in any way negate it. This is a trait of moderately progressive consciousness: such is the opinion of leftist theorists, and the capitalists have no real objections to their equitable thesis. We should play the idiot and simply declare this thesis a lie. We know quite well whose interests are served by it.

Being Productive?

Master Bertolt said that a person should be productive. Following his method of thinking, we might boldly claim that a person should be unproductive or that a person should not be productive. We end up with a big mess. We can get ourselves out of this muddle by asking a single question: to what end should we be productive? By constantly asking ourselves this question, we can resolve various working situations and understand when it is worth producing something and when it is not.

On Compromises

Politically engaged artists inevitably face the question of compromise in their practices. It primarily arises when they have to decide whether to take money from one or another source, or participate in one project or another. There are several readymade decisions to which artists resort. Some artists keen endlessly that it is impossible to stay pure in an unclean world and so they constantly wind up covered in shit. Other artists regard themselves as rays of light in the kingdom of darkness. They are quite afraid of relinquishing their radiant purity, which no one could care less about except themselves. The conversation about the balance between purity and impurity is banal, although finding this balance is in fact the principal element of art making. Master Bertolt suggested us to “drink wine and water from different glasses.”

On Working with Institutions

It is too little to postulate that collaborating with cultural institutions is a good thing or, on the contrary, that it is a bad thing. We should always remember that it is worth getting mixed up in such relations only when we try to change these institutions themselves, so that those who come after us will not need to waste their time on such silly matters and will immediately be able to get down to more essential work.

On Subjugation to the Dominant Class

We cannot deny the fact that the great artworks of the past were produced despite the subjugated position of their creators. As we recognize this fact today we should emphasize the vital proviso “despite.” We thus constantly remind ourselves what art could and should be if the subjugation to the dominant classes and tastes could disappear.

On the Historicity of Art

Like everything else in the world, art is historical. What does this mean?

First of all, it does not mean that what was created in the past has no meaning today.

Master Bertolt and Master Jean-Luc demonstrated that art is something that arises from difficulties and rouses us to action.

Those who deny art’s dependence on the powers that be are stupid.

Those who do not see that people’s creative powers never dry up, even in the face of slavery and hopelessness, are blind.

The essence of the great method is to assist the power of creativity in overcoming its dependence on the system of art.

The Formula of Dialectical Cinema

As Master Jean-Luc quite aptly noted, “Art is not the reflection of reality, but the reality of this reflection.” To this we should add that this reality is transformative. It has less to do with life as it is, and more to do with how the conditions of people’s lives can and must change.

On the Boundaries of the Disciplines

It is believed that we should have long ago put an end to the division of knowledge into separate disciplines. The mantra “knowledge is one” is hugely popular with many progressive people. They say that there is only one kind of knowledge, which serves the cause of emancipation.

And they are right insofar as there is hardly any sense in using the proud word “knowledge” to describe methods for enslaving consciousness. It is a good cause to use all our powers to bring closer that day when the disciplinary divisions will disappear, but it is premature to speak of this today. We should say rather that knowledge is one, but for the time being it consists of many disciplines. We must try and achieve perfection in each of them. For now this is the most important contribution we can make to the cause of emancipation.

On the Question of Self-Education

More and more often we hear that all imposed forms of education are unavoidably evil, that we should close all schools and organize ourselves into non-hierarchical circles in which there would be no difference between the learned and the ignorant, old and young, man and woman, the person born in misery and the person born with a silver spoon. All this sounds nice and of course we know the historical origins of such ideas.

Born at a certain historical moment, they played a supremely important role in transforming all of society and shifting capitalism to a new stage — the knowledge economy, the flexible labor market, exploitation of the general intellect, etc. Does it make sense for those who see all the dead ends of this path of development to repeat these new truisms of capital?

Let us leave the rhetoric of self-education to the corporations, which have such a need for the newly flexible worker willing to engage in lifelong learning.

Why shouldn’t we again think hard about creating a methodology of learning and teaching that takes account of the contemporary moment?

On the Theory of the Weakest Link

The question of where a breakthrough is possible, in what countries — that is, where it will be possible to create new relations outside the dominion of private property and the egotistical interests of individuals — is the most vital question.

The theory of the weakest link proved its utility in the past. Can it prove workable again? On the one hand, we are witnesses to capital’s unbelievable experiments in the development of technology and new forms of life. On the other, we see clearly that the period of prosperity in the First World, paid for with the slave labor of the rest of the world, led to a situation in which even oppressed people in the First World became more bourgeois. Their class consciousness, even in the most progressive circles, is bourgeois consciousness. In the West, even the most out-and-out punk is bourgeois to a certain extent. The situation outside the First World, however, looks just as hopeless. Since the emergence of cognitive capitalism, the colonial hegemony of Western countries has only grown. Detecting new emancipatory potential in the Third World is no less difficult than in the First World, despite the fact that it is precisely here that forms of collective consciousness have been preserved.

We should pay close attention to newly emergent enclaves of the Third World within the First World and of the First World on the periphery. If they cooperate in the future they might become a revolutionary force capable of changing the world. And of course we should carefully analyze everything that is happening in Latin America.

On the Withering Away of Art

To create an art that withers away — that is, a powerful art that disappears as its functions disappear, an art that reduces its own success to naught — we should build its institutions dialectically. That is, to begin with we need to generate a healthy conflict and then devise a mechanism that would enable us to abolish the gap between the act of creativity and the system that represents it.

This is only possible, however, given a total transformation of the entire system of power and political relations. Here the forces of art (even an art that is withering away) are insufficient. Although we also should affirm that unless art’s function is changed right now, any transformation of power relations will prove impossible.

On the Utility of Reading, Viewing, and the Supreme Privilege

Many people greatly enjoy reading, viewing films, and visiting museums. There is nothing wrong with this. What is wrong is that in our society only a tiny minority is capable of creating something from their experience of reading books, watching films, and visiting museums.

There is an old argument. Should art dissolve into life, or should it, on the contrary, absorb the entire experience of life and express it in new forms? Which position is the most correct one today?

Art should absorb the entire experience of life and express it in new forms. The principal task of these new forms — to come back transformed and dissolve into life, thus provoking life’s transformation — is to change the world, the thing that everyone so loves talking about.

Ideas and the Masses

Ideas mean nothing unless they seize the consciousness of people. Does this principle allow us to judge the quality of ideas? No, it does not. History teaches us that ideas need time in order to possess the consciousness of many people; it is a lengthy process. We can say with certainty, however, that ideas that do nothing to possess people’s consciousness mean very little. Therefore we have only ourselves to blame for the fact that we have remained unpersuasive.

On Universality

A universal method might well be applied to a multitude of particular cases. But the great method is unlikely to arise from a multitude of particular cases.

On World Art

Everyone remembers how the Great Teacher wrote in a manifesto about the origin of world literature. Who would be so bold as to talk about world art today? Of course this would sound totalizing and bombastic. Statements of this sort will always appear suspicious.

It is just for this reason that we should try to speak of world art.

On Leaders

Even in the most horizontally democratic organization the police can fairly quickly determine who they should arrest in order to paralyze its work.

We should consider organizational models in which this situation would be inconceivable. We don’t need an absence of leaders, but a surplus. Only when each of us becomes a leader can we reject this notion itself. For the time being, however, we should not forget that our leaders need special protection from the police.

The brightest minds are willing to write and meditate on the dialectic, but only a few of them are capable of doing this dialectically. The best artists make works on politics, inequality, and ordinary people, but only a few of them do this politically.

The best politicians try to mitigate people’s hardships — to guarantee that their rights and freedoms are observed, to help the weak and the sick — but only a few of them are capable of questioning the very system of relations that destroys, robs, and cripples people.

On Defamiliarization and Subversive Affirmation

“Negation of Negation,” Ivan Dougherty Gallery, Sidney, 2005 |

Nothing has so spoiled the consciousness of the handful of politically minded contemporary artists than using the method of subversive affirmation. Many of them have decided that this is the most appropriate method for critiquing society and raising consciousness. But is this the case?

It is as if everyone has forgotten that capital has no sense of shame, that it is essentially pornographic. Of course it’s tempting to turn soft porn into hardcore, but what does this change? This does not mean that we should discard these methods altogether. We should simply always employ them in the right proportions. It is not enough to make shit look shittier and smell smellier. It is vital to convince the viewer that there is also something that is different from shit. And we shouldn’t count on the fact that viewers will figure this out for themselves.

Is It Possible to Make Love Politically?

Master Bertolt said that love between two people becomes meaningful when a common cause arises between them — serving the revolutionary cause or something of the sort. Only then are they able to overcome their finitude in bed as well.

The most vivid example of dialectical affirmation in history is Benjamin’s thesis that communists answer the fascist “aestheticization of politics” with a “politicization of art.” It turns out that aesthetics is on the side of fascism, while art is on the side of the communists. I think that we shouldn’t so easily farm out aesthetics to history’s brown-shirted forces. Today we should re-examine this thesis and, most likely, conclude that we really lack an aesthetics of the politicization of art.

Dmitry Vilensky is a member of Chto Delat, an artistic collective is based in St Petersburg, Russia. This article was first published by European Alternatives on 20 January 2010 under a Creative Commons license. See, also, Chto Delat, “Partisan Songspiel: A Belgrade Story”; and Chto Delat, “Perestroika Songspiel.”

|

| Print