When is a tax haven not a tax haven? When Mauritius’ Vice Prime Minister Ramakrishna Sithanen says so. “We are a not a tax haven,” stated Sithanen, who is also the country’s Minister of Finance. Ironically, Sithanen would go on to reveal that ring-fenced financial services (FS) — the legal and financial secrecy vehicles facilitating corporate mispricing and corruption marketed to foreign clients, especially India — accounts for 12.5% of GDP.

Mauritius is already India’s largest single source foreign investor at $39 billion, almost half of total investment flows. The beautiful tourist island of Mauritius also provides 44% of capital “invested” in India, followed by Singapore at 9%. This often occurs through “round-tripping” where Indians, keen to evade and avoid taxes, park their wealth in Mauritius before “re-investing” in India — tax free.

But Sithanen, the architect behind Mauritius’ strategy to become Asia’s leading “financial centre” of choice, has the OECD backing his claim and removing Mauritius’ name from the list of “uncooperative tax havens” following ratification of “bilateral tax arrangements” related to “suspected tax evasion” — and “data on request only.”

Mauritius hosts 169 multinational subsidiaries as well as “big four” accounting firms, noted for the boutique “tax planning” products peddled by their accountants. Just two years ago, investigations by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) revealed that of the 100 largest US companies, over 37 entities were present in Mauritius, with 83 corporations, such as Exxon Mobil (122), Lehman Brothers (141), and Morgan Stanley (568), maintaining subsidiary units in multiple jurisdictions.

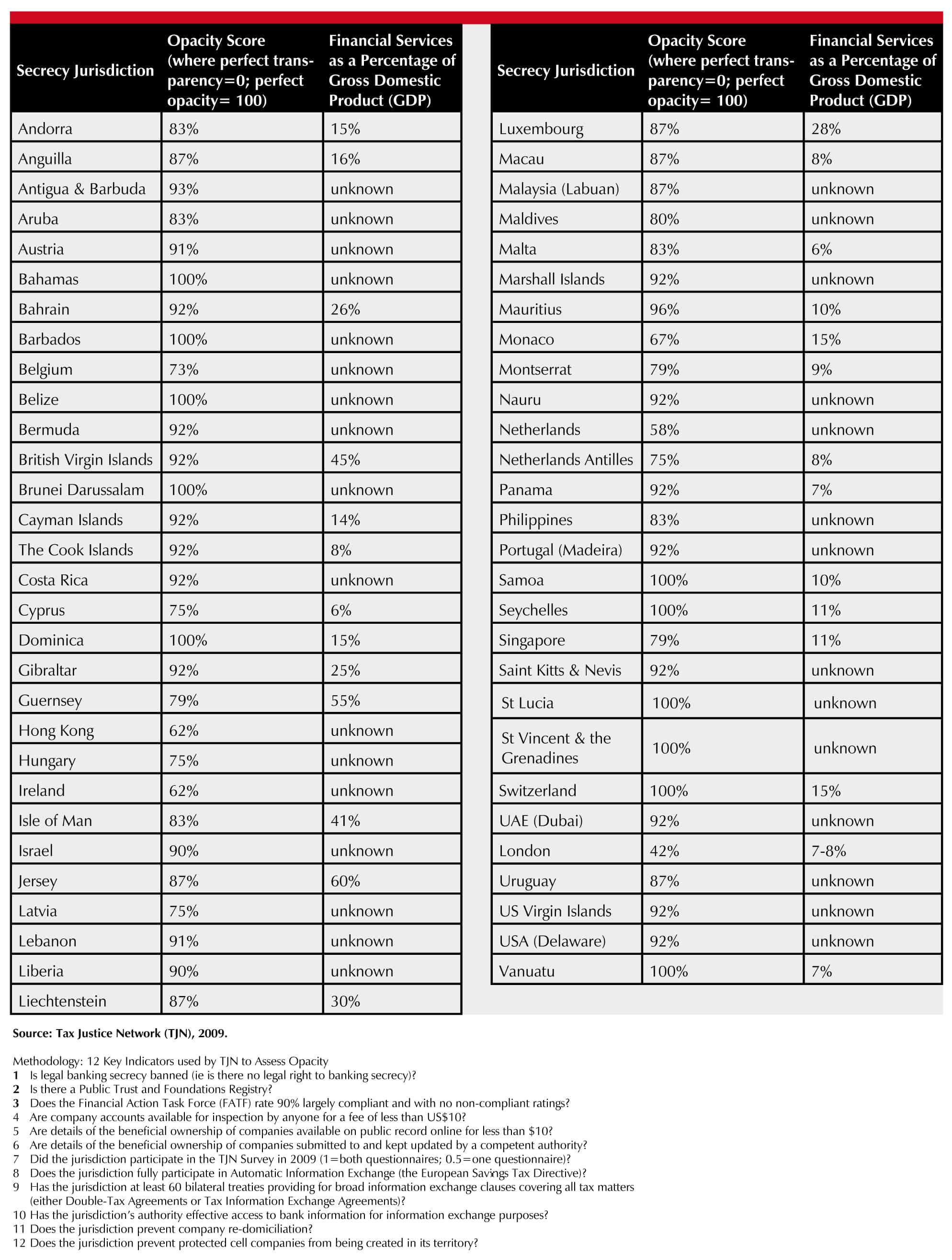

According to research by the Tax Justice Network (TJN), Mauritius has an “opacity” score of 96 (where perfect transparency rests at 0 and perfect opacity stands at 100) following assessments of FS using 12 key indicators (see Table: Global Secrecy Jurisdictions Opacity Scores and Financial Services as a Percent of GDP). This includes banking secrecy though a number of means: by not placing details of trusts on public records, not sufficiently complying with international regulatory requirements nor requiring that company accounts be available on public record, and not maintaining company ownership in official documents. The country has few tax information agreements, allows for company re-domiciliation and protected cell companies, and does not provide adequate access to banking information.

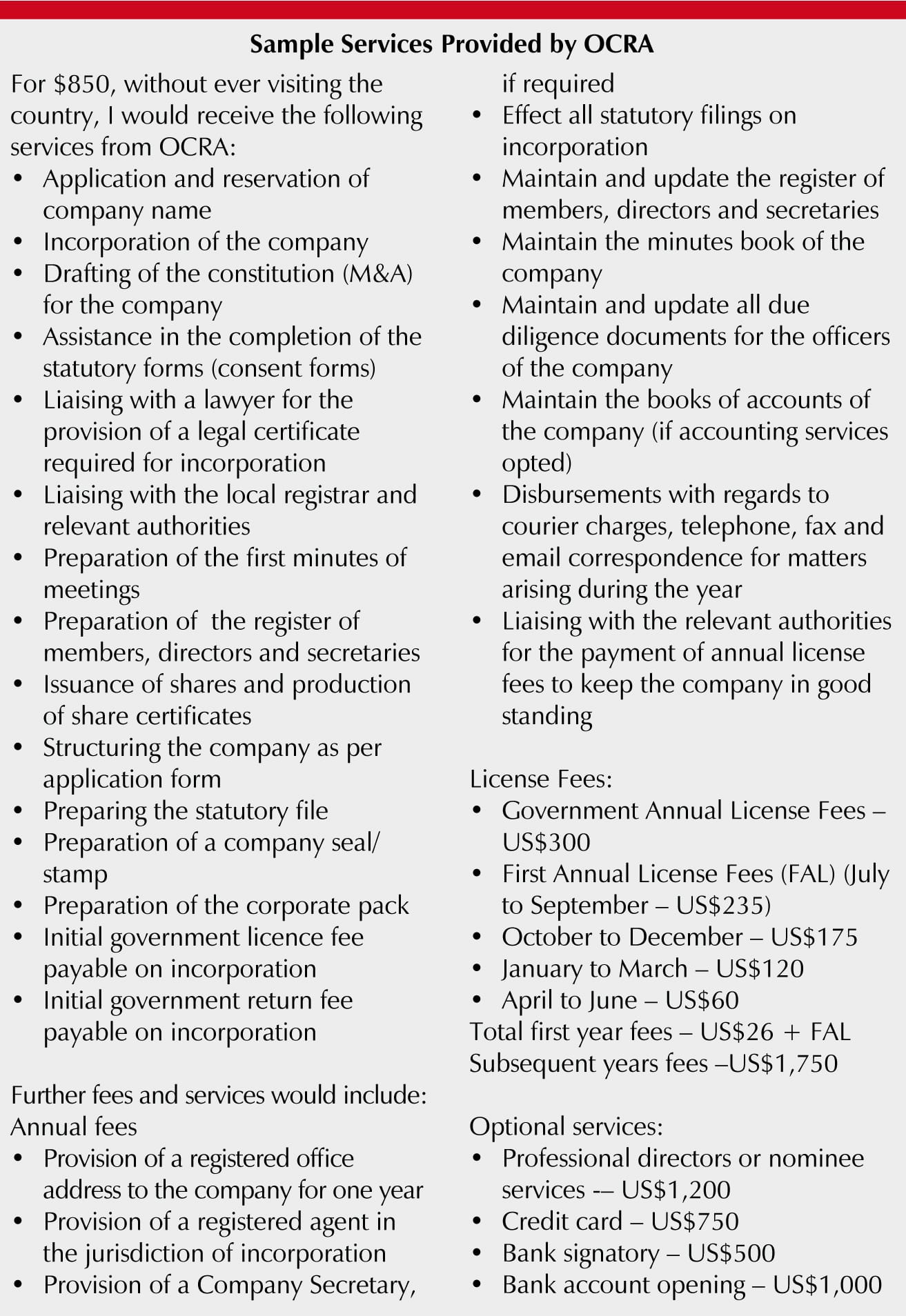

Queries into this cesspool of secrecy are effectively blocked, as even bilateral treaties require separate court orders for disclosure. “Whenever a judge asks for information from Mauritius during an investigation, there’s no response,” revealed investigative anti-corruption magistrate Renaud van Ruymbecke of the Paris Pole Financier du Tribunal. “I recommend Mauritius and Singapore to those with dirty money to launder.” Posing as a citizen anxious to shift my own wealth offshore to exempt profits from taxes, I was informed by OCRA, an internationally respected corporation peddling offshore shelf companies, that it could be done with as little as an ID, a credit card statement showing my proof of address, and curriculum vitae (www.ocra.com). Potential investors must sign an application form, provide consent of shareholder and director, and reveal “the source of funds, financial forecast and geographic location of business,” amongst other requirements (see sidebar). In my initial correspondence, I stated that the “business in question yielded significant profit, but the owners, fearful of the political climate, would like to shift their profits to a jurisdiction with high levels of client confidentiality and low tax rates.” The source of my funds? Massive profits generated from . . . egg cartons. And just in case my lucrative “egg carton” business might be caught out, the manager kindly responded to my anxious statements saying, “There is information-sharing only on money laundering and terrorist matters; otherwise, all information remains confidential.” I was also told that although the tax rate for companies is officially 15%, this could be reduced to zero by opting for the Global Business Company (Category II). At the bottom of the first page of the application, the document states: “Company services for private clients only: privileged information.”

Queries into this cesspool of secrecy are effectively blocked, as even bilateral treaties require separate court orders for disclosure. “Whenever a judge asks for information from Mauritius during an investigation, there’s no response,” revealed investigative anti-corruption magistrate Renaud van Ruymbecke of the Paris Pole Financier du Tribunal. “I recommend Mauritius and Singapore to those with dirty money to launder.” Posing as a citizen anxious to shift my own wealth offshore to exempt profits from taxes, I was informed by OCRA, an internationally respected corporation peddling offshore shelf companies, that it could be done with as little as an ID, a credit card statement showing my proof of address, and curriculum vitae (www.ocra.com). Potential investors must sign an application form, provide consent of shareholder and director, and reveal “the source of funds, financial forecast and geographic location of business,” amongst other requirements (see sidebar). In my initial correspondence, I stated that the “business in question yielded significant profit, but the owners, fearful of the political climate, would like to shift their profits to a jurisdiction with high levels of client confidentiality and low tax rates.” The source of my funds? Massive profits generated from . . . egg cartons. And just in case my lucrative “egg carton” business might be caught out, the manager kindly responded to my anxious statements saying, “There is information-sharing only on money laundering and terrorist matters; otherwise, all information remains confidential.” I was also told that although the tax rate for companies is officially 15%, this could be reduced to zero by opting for the Global Business Company (Category II). At the bottom of the first page of the application, the document states: “Company services for private clients only: privileged information.”

The box-ticking exercise in Section Two of the application form reveals why Eva Joly — the former investigative anti-corruption magistrate who cracked the Elf Affair1 — burst out laughing when describing how “nine nominees can administer 1,500 companies.” The questions in Section 2 are:

- Would you like OCRA Worldwide to arrange for the appointment of professional directors to this company?

- Would you like OCRA Worldwide to provide nominee shareholders for this company?

- Would you like OCRA worldwide to assist in the establishment of a trust or foundation to own this company?

A simple yes or no does the trick.

It’s not just India that suffers from the $1.6 trillion draining maldeveloped nations of revenue due to round-tripping. Many multinationals exploiting African resources — often cheapened through the IMF-imposed policy of “tax competition” — extensively utilise Mauritius. And Mauritius seems bent on establishing itself as Africa’s financial “gateway” for foreign investors.

One example of such draining, as quoted in Faim et Développement Magazine, was described by Joly (currently President of the European Parliament’s Development Committee) who revealed that “Zambian copper producers make use of Mauritius to export its copper. An offshore subsidiary buys Zambian copper at €2,000 per tonne to resell at €6,000. €4,000 of profits are retained by the subsidiary . . . untaxed. Under this arrangement, the Zambian government doesn’t get a single Euro of tax on the profits.”

“According to our sources, including a Swiss banker, Mauritius is attracting a lot of dirty business migrating out of Europe in response to the EU savings tax directive. European banks are enlarging their offices in Port Louis because they regard the government there as pliable and largely indifferent to the OECD processes,” stated John Christensen, founder of TJN and former senior official of Jersey, a major secrecy jurisdiction. “Mauritius is, therefore, rapidly emerging as a major centre for money laundering and tax evasion and avoidance in the southern hemisphere,” he added.

But it is unlikely that the OECD would curb this kind of structural injustice which is embedded within the global financial architecture because most “developed” nations on the OECD’s member list are systemically powerful onshore ring-fenced “treasure islands,” on the receiving end of $385 billion in corporate evasion and avoidance from developing countries annually. Such examples include the US (through the state of Delaware); the UK (controlling more than a quarter of tax havens globally through overseas territories operating from the City of London with an FS at 9%/GDP); and Switzerland (washing one-third of illicit flight with an FS at 15%/GDP).

Yet according to the OECD, “Since May 2009, no jurisdiction is currently listed as an uncooperative tax haven by the Committee on Fiscal Affairs.” Cooperation itself is limited to bilateral tax arrangements, dealing specifically with terrorism as well as hard evidence pertaining to tax evasion.

This was echoed by French President Nicholas Sarkozy who stated in September 2009: “There are no tax havens anymore.” He was no doubt keen to shift attention away from Monaco (FS 15%/GDP), the playground refuge for the rich and wealthy, situated on the French Riviera. Monaco’s foreign clients are more than triple the number of Monaco’s citizens, chiefly from France. Not only does Monaco share banking information only with France, but Monegasque authorities are able to access this information in accordance with France via treaty arrangements, favouring the latter, and thereby preventing authorities and regulators from accessing the legal and financial details of 3,950 offshore companies and 725 trusts under Corporate Service Provider (CSP) management (2002), revealed a TJN study.

When charting illicit flows — defined as money illegally generated, transacted or utilised through methods of tax avoidance and evasion — onshore and offshore “treasure islands” have acted as conduits. According to analysis by Tax Justice Network assessing data produced by Merrill Lynch/CapGemini, Boston Consulting, McKinsey and the Bank for International Settlements, at least $13 trillion in private wealth has been concealed, siphoned by tax evaders and avoiders to secrecy jurisdictions. If taxed at a moderate 7.5% rate of return, offshore assets — increasing at 9% per annum and constituting a significant portion of OECD “donor country” GDP — would yield $865 billion dollars annually.

But mandatory information exchange, previously scrapped from the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, is marginalised as impractical. Ironically, the OECD’s “on request” bilateral tax arrangements have been publicly discredited by entities peddling supply-side corruption. “This exchange can only take place if the individual can be identified, the bank account can be identified and sufficient evidence to prove evasion is provided to the Swiss courts. There is no automatic exchange of information and ‘fishing trips’ are specifically excluded,” revealed Switzerland’s Louvre Group, with branches in London, Geneva, Cayman Islands, Guernsey and Hong Kong. The statement, available on their website for potential customers to peruse, renders the law a mockery.

The narrow geography of “corruption” has been limited to behavioural “demand-side” activities ie: corruption on the part of state officials for public gain. This definition was launched by corruption watchdog Transparency International, and ratified by resource-seeking and financial multinationals, and developed governments — systemic providers of supply-side corruption such as the Louvre Group.

And because Africa’s often ineffective tax and revenue administrations have been structured to serve as recipient vessels of Large Taxpaying Units (LTU), multinationals — Africa’s primary “renters” conducting 60% of global trade, within rather than between corporations — are easily able to exploit vacuums. This includes using self-regulated “arms length transfer” pricing principles, designed by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) as a mechanism motivating for market price. But there is no external body to hold them to account because corporate Country-by-Country reporting (CbC), which is a tool that helps reveal economic activities in resource-rich regions, is not mandatory.

Examples of transfer (mis)pricing that occurs within corporations between subsidiaries to decrease costs or increase profits, includes rocket launchers exported for $52 each and plastic buckets imported for a nominal value of $972 each. “Self-regulation by the IASB, funded in large part by the ‘big four’ accounting firms, are in the interests of its funders, not society,” said accountant Richard Murphy, founder of CbC and head of Tax Research LLP.

In 2006, the IASB rejected CbC, a version of which already functions smoothly in the US, monitoring corporate activities such as taxes and other revenues remitted to the state, imported materials, labour, and the basis for determining profits, pricing goods and allowable costs, amongst other details. “A member stated, ‘This looks like it deals with transfer pricing, and we don’t want to go there,'” revealed Murphy. High-level research by the TJN reveals that 99% of the 97 largest quoted companies in France, the Netherlands and the UK use secrecy jurisdictions while a further 80% of 476 companies surveyed in another study declared transfer pricing crucial to corporate strategy. Paradoxically, “first world” secrecy jurisdictions feature at the top of TI’s “clean lists,” while African nations in particular, almost uniformly occupy the bottom ranks.

The paradox of “donor countries” actively incentivising the flow of illicit flight was interrogated in depth by Washington-based Global Financial Integrity‘s director Raymond Baker who stated in testimony before the US House of Representatives (2009): “For every dollar Western governments have been handing out across the top of the table, crooked Western banks, businesses and middlemen of various descriptions have been taking back up to $10 dollars of illicit proceeds under the table.”

Illicit flows from the continent are a very serious drain on African economies. During the recently held World Economic Forum in Tanzania, the Tanzania Daily News (7 May 2010) reported: “The African continent, which many international investors describe as too risky to invest in, loses between US$200 billion and US$400 billion annually in capital flight by firms which make super profits through evading or cheating the taxman.” Such siphoning occurs through corporate mispricing (60%), political corruption (5%), and criminal in-fighting (30- 35%). As James Boyce and Leonce Ndikumana (African Development Bank), note: “Adding to the irony of sub-Saharan Africa’s position as net creditor is the fact that a substantial fraction of the money that flowed out of the country as capital flight appears to have come to the subcontinent via external borrowing.”

According to the UN Commission of Experts on the Financial and Monetary System, the G20’s policies via the OECD to curb “harmful tax practices” was geared toward “discriminatory targeting of small international financial centres in developing countries while a blind eye is turned to lax rules in developed economies.” They went on further to state that the chief sources of evasion are situated “in developed countries’ on-shore banking systems,” including the City of London and the US’s Delaware.

In the case of Delaware, foreign clients “investing” onshore in this area are deemed tax-exempt, save for annual “franchise” taxes, as corporate income tax applies only to those unfortunate enough to conduct economic activity in Delaware. With an opacity score of 92% and over 1,104,700 lawyers active in the state, Delaware peddles legal and financial secrecy vehicles such as banking secrecy policies and lack of disclosure related to trusts, beneficial owners of companies and company accounts as well as allowing company re-domociliation and protected cell companies.

Meanwhile, though the onshore City of London has an opacity score of 42% (blocking company re-domociliation, protected cell companies and banking secrecy), according to an official from the Serious Fraud Office (as revealed to TJN Director John Christensen), these “tax havens are little more than booking centres. I’ve seen transactions where all the decisions are made in London, but booked in havens.” These include one quarter of all secrecy jurisdictions globally, including Guernsey (opacity score 79%; FS 55%/GDP), Jersey (opacity score 87%; FS 60%/GDP), and the British Virgin Islands (opacity score 92%; FS 45%/GDP).

Examples of remote-controlled use administered from different jurisdictions are prevalent throughout onshore and offshore entities. One such institution is the Louvre Group, marketing Guernsey Protected Cell Companies (PCC), a cellular corporate structure that allows assets to be held within individual cells. The assets of any one particular cell are only available to the shareholders and creditors of that cell while creditors of another cell have no recourse against them. The “core” company (established and managed by a Guernsey financial services provider such as Louvre) is able to create cells, thereby isolating wealthy individuals from risks, disclosure and taxation.

The use of “tax minimisation” strategies via tax planners retained and trained by the “big four” auditing and accounting firms — PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte & Touche Tohmatsu, KPMG and Ernst & Young — extends all the way back to the heyday of the British Empire, via the Duke of Westminster ruling decided at the House of Lords of the United Kingdom in 1936. The ruling, still the cornerstone of the Britain’s unofficial “supply-side corruption” empire, stipulates that “the “taxpayer has the right to order affairs as he (sic) sees fit to minimise his tax payable.”

With combined revenue of more than $100 billion, these hyper-mobile economies exploit the weak political capital of “offshore” treasure island economies, renting out secrecy spaces as befits foreign clients.

The “big four,” of course, are present and active in Mauritius, Guernsey, Jersey and most other secrecy jurisdictions. Through vehicles such as KPMG’s Tax Innovation Centre, the “tax avoidance” industry has undermined Africa’s fiscal independence, by draining the continent of revenue — 80-90% of which remains permanently offshore. South Africa, which has the largest number of millionaires on the African continent, loses an estimated 9.2% of GDP when adjusted for illicit flight.

Like Ghana, Botswana, Seychelles, Liberia and Djibouti, Mauritius — marketing itself through the slogan, “How Best Can We Serve You” — serves as a crucial conduit for tax avoidance, rendering Africa subject to captured states lending to expanding informal sectors, aid dependence and enclave maldeveloped economies structured around unearned resource revenues.

Speaking in the UK parliament in November 2009, South African finance minister Pravin Gordhan noted that: “We have allowed the word avoidance to gain too much respectability. It is just a smarter form of evasion.” Damn right.

Table: Global Secrecy Jurisdictions (N = 60)

Notes

1 The “Elf Affair” was Europe’s biggest corruption scandal since World War II. It was rooted in Gabon and to a lesser extent, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s oil industries, where laundering profits through secretive offshore financing was made available to select segments of the French elite as well as Gabonese and Congolese officials.

Khadija Sharife is a journalist and co-author of Aid to Africa:

Redeemer or Coloniser? (Cape Town: Pambazuka Press, 2009). This article was first published in The Thinker 16 (2010) under a different title; it is republished here with the author’s permission.

| Print