Andrej Grubacic. Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! Essays after Yugoslavia. Introduction by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. PM Press, 2010.

This is not a typical book review and I am not a detached reader. The book’s author, Andrej Grubacic, is a friend and collaborator, a comrade in the truest sense of the word. And as he makes clear throughout Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! Essays after Yugoslavia, to be Yugoslav is to be implicated, to speak for yourself only through the filters of history, of shifting imperialisms, of age-old hatreds. Like Andrej, I too am Yugoslav, having been born in Belgrade to parents with roots in three of the post-Yugoslav republics. So I read and reflect on this collection of essays, originally written between 2002 and 2010, in the context the trajectory of my own life as both a Yugoslav and a leftist, weighing it as lived history of resistance as well as an abject lesson in the failure of the North American Left.

For many of the same reasons, Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! is not an introduction — for radicals or otherwise — to the histories of the region generally or the destruction of Yugoslavia more specifically. There are tantalizing gestures toward these narratives, especially in Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s excellent introduction, which succinctly discusses some of the now little-remembered internationalist history of Yugoslavia, particularly its leadership within the Non-Aligned Movement and the related New International Economic Order initiative. The timeline of major events during the period covered by the essays is also helpful, as are the suggestions for further reading made by Andrej in his introductions to the essays. But for the most part, this is a work of analysis and polemic, rather than a comprehensive historical account.

Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! is divided into two main sections — on balkanization from above and balkanization from below — both chronologically organized and both revolving around the same themes: the politics of exclusion, intervention, and resistance, within and beyond the Balkans, but especially in Serbia, Bosnia, and Kosovo. In the first section, Andrej reflects on the continuing efforts to impose balkanization from above in the aftermath of the break-up of Yugoslavia, the NATO’s bombing campaign, and Kosovo’s declaration of independence. This initial batch of essays covers the “most recent phase in colonial ordering of the Balkans,” a project rooted in “deep-seated cultural derision” and encompassing the efforts of both external powers and “local self-colonizing intelligentsia.” As with the destruction of state-socialist Yugoslavia, the current context is the latest example of a “century-long process of balkanization from above” — a practice, which has remained “remarkably consistent in history, of breaking Balkan interethnic solidarity and regional socio-cultural identity; a process of violently incorporating the region into the system of nation-states and capitalist world-economy; and contemporary imposition of neoliberal colonialism” (43).

To some degree, this is not a new argument; Yugoslav third-way socialism, viewed as what Chomsky terms the “threat of a good example,” has always been part of critical accounts of the republic’s demise, despite its concomitant geopolitical centrality during the Cold War. Yet Andrej’s analysis is wider than the typical politico-economic reading of Yugoslav state socialism, being equally grounded in notions of historicity and culture. In addition to discussing the impact of war, sanctions, and neo-liberal state-building on the post-Yugoslav republics (in essays on the Milosevic trial, the Kosovo war, and Roma struggles), he also canvasses the literary, cultural, and political portrayals of the Balkans as wild, savage, and uncivilizable which prop up the central narrative. Andrej argues that, after the “defeat of real existing socialism, the Yugoslav state, with its indigenous socialism, and its global south, nonaligned orientation, could no longer be tolerated” (43). Unfortunately, this thread is fully explored only in the essays on balkanization from below, but, from the onset, it is clear that top-down balkanization is also about an extra-political process of marginalization and exclusion that takes different forms but is consistently predicated on the Balkans as “other,” uncivilized, savage, wild. Nor is this telling of the post-Yugoslav story one solely about the usual hegemonic suspects of “humanitarian” intervention (e.g. NATO members and/or the Security Council). Among those in the region, Andrej suggests, the “opinion that prevails is that the differences between Western allies today are of an essentially strategic rather than of a moral nature” (86). In describing a post-Yugoslav politic bounded by the siren call of Europe and the EU, the military power of the NATO (and especially its guiding light, the US), and the more diffuse but no less powerful constraints of global capitalism (what I’ve referred to elsewhere as the “Belgrade-Brussels-Bretton Woods matrix”), Andrej’s analysis highlights the complex, contradictory, and contingent character of struggles for social justice in the Balkans. In describing the existence of what he calls the “Belgrade consensus” — a mix of neo-liberalism, nationalism, and a “civil society” made up of “rent-an-intellectuals and NGOs” adding up to a self-imposed internal civilizing mission — Andrej draws the link between balkanization from above and below, the moment where the meaning of “balkanization” gets flipped, and both the pathways and obstacles to resistance become evident. This is an important contribution to the need to develop complex, multi-layered conceptions of Empire and imperialism and to challenge the emancipatory potential of local elites who draw on external agents for power and influence.

The second half of Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! develops this alternative, rebellious, emancipatory conception of balkanization from below, at once an idea(l), a strategy, and a way of seeing both the past and future of the Balkans:

The Balkans I know is the Balkans from below: a space of bogoumils — those medieval heretics who fought against Crusades and churches — and a place of anti-Ottoman resistance; a home to hajduks and klephts, pirates and rebels; a refuge of feminists and socialists, of antifascists and partisans; a place of dreamers of all sorts struggling both against provincial “peninsularity” as well as against occupations, foreign interventions and that process which is now, in a strange inversion of history, often described with that fashionable phrase, “balkanization.” (11-12)

|

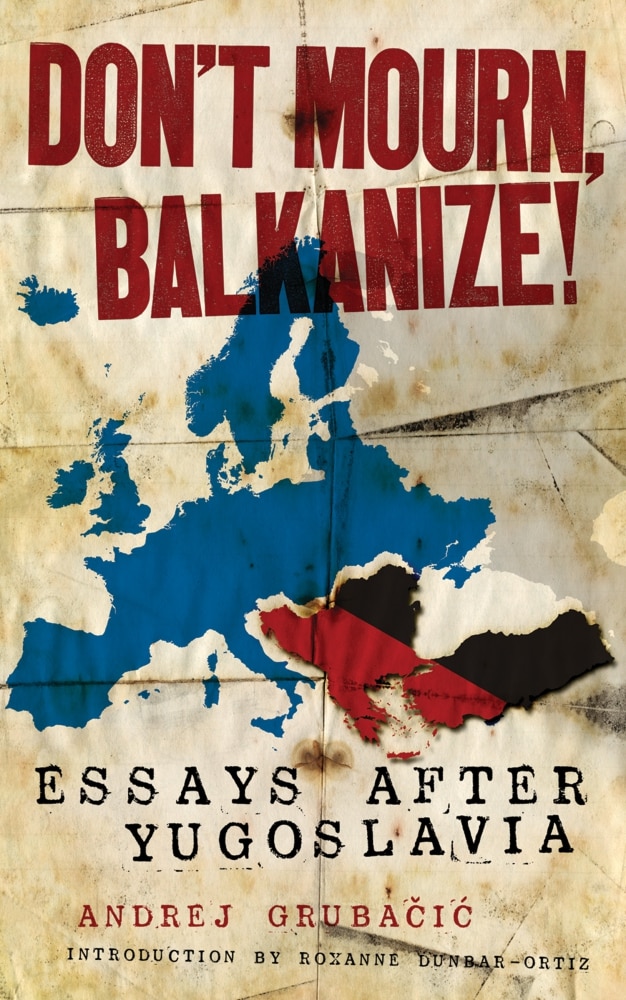

In his articulation of “balkanization from below,” Andrej draws on the imperative of reconciling revolutionary imagination and the material forces of history. The most powerful element of Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! builds on previous calls for the development of a Balkan Federation through a quasi-utopian yet resolutely concrete elaboration of the politics of balkanization from below described alternatively as a “tradition and narrative that affirms social and cultural affinities as well as . . . customs in common resulting from interethnic mutual aid and solidarity” (158) and an “alternative process of territorial organization, decentralization, territorial autonomy, and federalism” (258). The book’s stunning cover art (by English graphic artist John Yates) echoes this theme, depicting a red and black Balkan peninsula, seemingly broken off from Europe yet at the same time inextricably bonded to it, their nesting edges marking both boundary and connection, or perhaps prefiguring a “balkanized Europe of regions,” premised on territorial autonomy and cultural plurality (266).

Andrej’s exploration of these fissures traces the recent trajectory of nascent post-Yugoslav social movements as well as their links to previous struggles and earlier progressive legacies, invariably running up against hard questions about how to account for both the current and very real divisions at play in the region and the pressing need to find a new vocabulary of resistance and liberation in a context where the language of the Left is suspect, tainted by the not-so-distant past. The book engages most concretely with these complex questions in interviews with the Serbia-based activists of Freedom Fight and a debate with writer Dragan Plavsic. The latter exchange deals seriously and pragmatically with the status of Kosovo, but raises broader questions which ought to lie at the core of radical left analyses of international relations: how to grapple with the actual, rather than idealized, politics of movements for self-determination and especially related claims to “national” or state sovereignty. The debate with Plavsic pits Andrej’s self-proclaimed “utopian program of transformation” against a nominally radical but state-based call for support for self-determination, in a contest of inclusion and “policy from below” against equally idealized, although ultimately cynical, ethnic-based realpolitik. Yet the Plavsic-Grubacic exchange only begins to scratch at the surface of the complex issues it touches on, and especially for readers lacking background information on Kosovo’s history and politics, it only begins a conversation that should hold greater resonance for the North American radical Left. Similar opportunities to consider our praxis in terms of international law emerge in the text, sometimes explicitly, as in the earliest essays on the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia or in the discussion of Serbia’s treaty with the US on non-extradition of US citizens to the International Criminal Court (a key ploy of recent US statecraft vis-à-vis its “allies”), but mostly implicitly, where Andrej’s anti-authoritarian analyses of humanitarian intervention, state-building, and the international human rights movement provide vital, if underdeveloped, insights into movement strategies and tactics, in the Balkans and beyond.

The complexity of such analyses within the post-Yugoslav republics is documented in Andrej’s interviews with local activists, accounts which chart the rise and fall of projects, campaigns, and coalitions, all of them fighting to organize and (re)assert movements for social change in a context where the nomenclature of “socialism,” “self-management,” and the “Left” is equally the language of failure, false promises, and unaccountable, undemocratic power. Andrej asks important questions about overcoming these legacies, not only of post-Yugoslav organizers, but also of Michael Albert, and their discussion of how to “sell” notions of participatory economics to workers with lived experience of flawed and/or partial self-management raises vital questions (not all of them answered), about catalyzing radical consciousness and the need for revolutionary praxis across communities of workers (rural and urban), farmers, students, and the like. Throughout the book, Andrej highlights the material conditions giving rise to these struggles, noting that, as in other post-socialist states, accumulation by dispossession (as framed by David Harvey) through privatization, commodification, and the management of “crisis” has wrought massive poverty, inequality, and deep social divides, if not outright breakdown. As Andrej documents, there has also been sustained resistance, yet these struggles often fail to engage the imagination or material support of radicals in the West and North. Following from the Left’s paralysis during the wars of secession and dismemberment in the early to mid 1990s and our divisive, unprincipled, and often instrumental response to the NATO campaign in 1999, the almost complete lack of international solidarity activism, or even base awareness, in terms of the Balkans is sadly not surprising. Read through this lens, Don’t Mourn, Balkanize! underscores the need to develop an emancipatory politic of post-socialist solidarity across networks and movements, in and beyond the post-Yugoslav republics. The Global Balkans Network, of which both Andrej and I are founding members, is attempting to begin this process, to shift the lens of post-socialist politics beyond the co-opted spaces of (neo)liberal human rights and the transnational non-profit industrial complex. In doing so, we aim at building a praxis of solidarity founded on shared opposition to dispossession and austerity and, ultimately, a transnational (perhaps post-national) movement for balkanization from below.

Irina Ceric may be contacted at <[email protected]>.

| Print