A recently published paper by three Yale scholars reveals “that Americans, on average, systematically overestimate the extent to which society has progressed toward racial economic equality, driven largely by overestimates of current racial equality.”

The authors based their conclusion on the results of three different studies. Participants in all three studies were asked to estimate differences between average Black and White Americans in five areas at a point in time in the past and the present. The areas and time points were:

(i) employer provided health care benefits in 1979/2010; (ii) hourly wages of college graduates in 1973/2015; (iii) hourly wages of high school graduates in 1973/2015; (iv) annual income in 1947/2013; and (v), accumulated wealth in 1983/2010. Participants considered an average White individual or family earning $100 U.S. and were asked to estimate how much an average Black individual or family would earn using a scale that ranged from $0–$200 US. For the health care item, the question was framed in terms of families with health coverage, and participants indicated how many Black families would be covered if 100 similarly employed White families had coverage. Participants were reminded that an answer of 100 meant equality between Whites and Blacks.

Two of the three studies included a sample of White and Black participants drawn from the top (over $100,000 yearly income) and bottom (below $40,001) of the income distribution. The third study included just White participants, also drawn from the two ends of the income distribution.

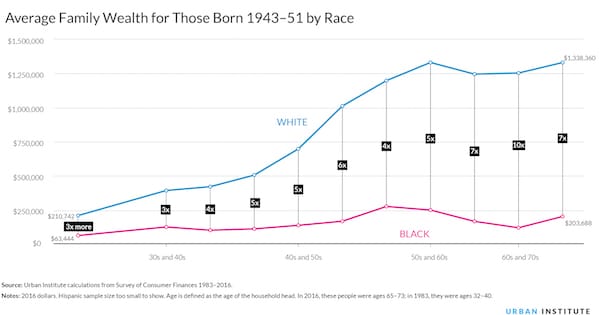

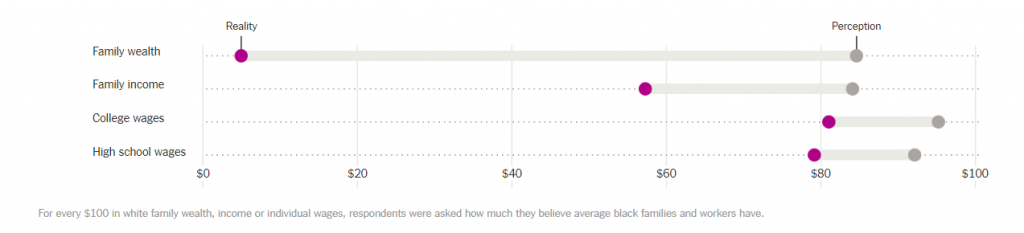

The following figure, taken from a New York Times review of the study’s results, shows the views of participants about current racial differences for four of the five survey areas.

As noted above, participants were asked how much they thought an average Black family or individual held in wealth or earned in income or received in wages, if the average White family or individual had $100 in wealth or received $100 in income or in wages. Their estimates are shown in grey while the reality is shown in red. As we can see, the general perception is that discrimination exists, but is relatively small. As we can also see, the reality, especially with regards to wealth and income, is far worse.

Because the authors asked participants to do this thought experiment for a period in the past as well as in the present, they were also able to draw some conclusions about people’s sense of progress in fighting discrimination. Their results:

confirmed our hypothesis that Americans, on average, misperceive the extent to which society has made progress toward racial economic equality . . . Indeed, participants overestimated racial economic progress by more than 20 points across all studies and all domains of progress.

They also found, again in line with another of their hypotheses, that high-income White participants were more likely to overestimate racial equality than were low-income White participants or Black participants of either income group. More specifically, high-income White participants overestimated past as well as current racial equality relative to the other three groups. In fact, “high-income White participants were actually the only subgroup to overestimate the extent of racial equality in the past.”

The New York Times article concludes:

Why would people get these questions so wrong — and consistently in the direction of too much optimism? (This study was also conducted after the 2016 election.) Blacks overestimated equality, too, but the biggest effects were among wealthy whites.

The researchers suspect that the answer in part has to do with how little exposure Americans have to people who are unlike them. Given how economically and racially segregated the country remains, many Americans, and especially wealthy whites, have little direct knowledge of what life looks like for families in other demographic groups.

We’re inclined, as well, to believe that society is fairer than it really is. The reality that it’s not — that even college-educated black workers earn about 20 percent less than college-educated white ones, for example — is uncomfortable for both blacks who’ve been harmed by that unfairness and whites who’ve benefited from it. . . .

The researchers found in some additional surveys that whites answer these questions more accurately when they’re first asked to consider an America where discrimination persists. If we want people to have a better understanding of racial inequality, this implies that the solution isn’t simply to parrot these statistics more widely. It’s to get Americans thinking more about the forces that underlie them, like continued discrimination in hiring, or disparities in mortgage lending.

Sadly, as this paper makes clear, too many people continue to believe the myth of American social progress. It is a myth that needs to be challenged if we hope to build a powerful working class-based movement for social change. This means we must continue to work to paint an accurate picture of the reality of racial discrimination and its terrible social consequences for Blacks and other people of color. But, as noted above, we will greatly increase the effectiveness of this effort if we also help White workers understand the underlying class-driven economic dynamics that encourage racial divisions and, even more importantly, in whose interests they work.