A lot has been written and said critical of millennials. The business press has been tough on their spending habits. As a recent Federal Reserve Board study of millennial economic well-being explained:

In the fields of business and economics, the unique tastes and preferences of millennials have been cited as reasons why new-car sales were lackluster during the early years of the recovery from the 2007–09 recession, why many brick-and-mortar retail chains have run into financial trouble (through lower brand loyalty and goods spending), why the recoveries in home sales and construction have remained slow, and why the indebtedness of the working-age population has increased.

Politicians, even some Democratic Party leaders, have tended to write them off as complainers. For example, while on a book tour, former Vice President Joe Biden told a Los Angeles Times interviewer that “The younger generation now tells me how tough things are. Give me a break. I have no empathy for it. Give me a break.” Biden went on to say that things were much tougher for young people in the 1960s and 1970s.

In fact, quite the opposite is true. For better or worse, the authors of the Federal Reserve Board study found that there is “little evidence that millennial households have tastes and preference for consumption that are lower than those of earlier generations, once the effects of age, income, and a wide range of demographic characteristics are taken into account.” More importantly, millennials are far poorer than past generations were at a similar age, and are becoming a significant force in revitalizing the labor movement.

Economic hard times for millennials

The Federal Reserve Board study leaves no doubt that millennials are less well off than members of earlier generations when they were equally young. They have lower earnings, fewer assets, and less wealth. All despite being better educated.

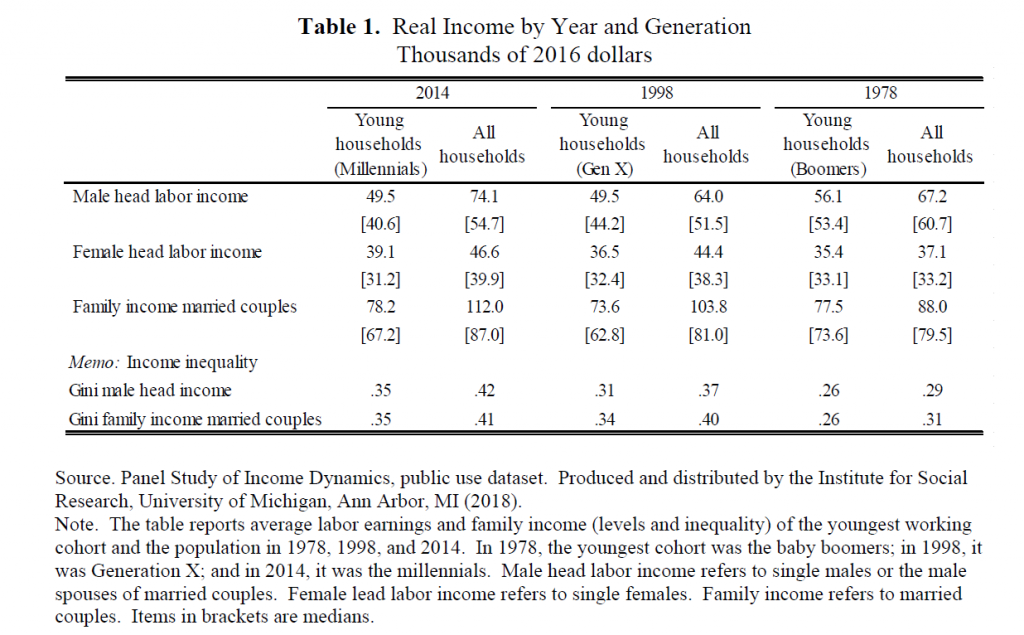

The study compares the financial standing of three different cohorts: millennials (those born between 1981 and 1997), Generation Xers (those born between 1965 and 1980), and baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964). Table 1, below, shows inflation adjusted income in three different time periods for all households with a full-time worker and for all households headed by a worker younger than 33 years.

The median figures, which best represent the earnings of the typical member of the group, are shown in brackets. Comparing the median annual earnings of young male heads of households and of young female heads of household across the three time periods shows the millennial earnings disadvantage. For example, while the median boomer male head of household earned $53,400, the median millennial male head of household earned only $40,600. Millennial female heads of household suffered a similar decline, although not nearly as steep.

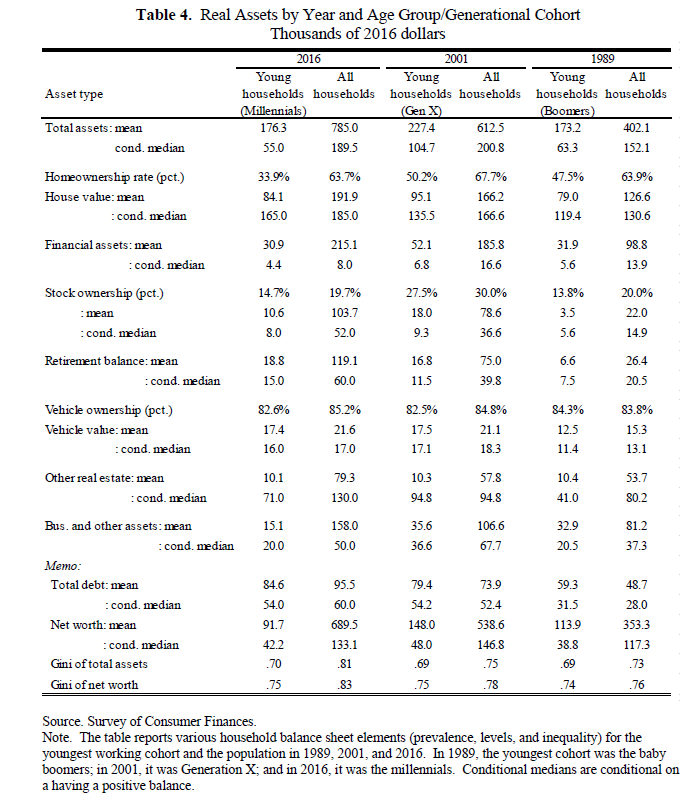

Table 4 compares the asset and wealth holdings of the three generations, and again highlights the deteriorating economic position of millennials. As we can see, the median total assets held by millennials in 2016 is significantly lower than that held by baby boomers and only half as large as that held by Generation Xers. Moreover, millennials suffered a decrease in asset holdings across most asset categories.

Finally, we also see that millennials have substantially lower real net worth than earlier cohorts. In 2016, the average real net worth of millennial households was $91,700, some 20 percent less than baby boomer households and almost 40 percent less than Generation X households.

Fighting back

Millennials have good reason to be concerned about their economic situation. What is encouraging is that there are signs that growing numbers see structural failings in the operation of capitalism as the cause of their problems and collective action as the best response. A recent Gallup poll offers one sign. It found a sharp fall in support for capitalism among those 18 to 29 years, from 68 percent positive in 2010 down to 45 percent positive in 2018. Support for socialism remained unchanged at 51 percent.

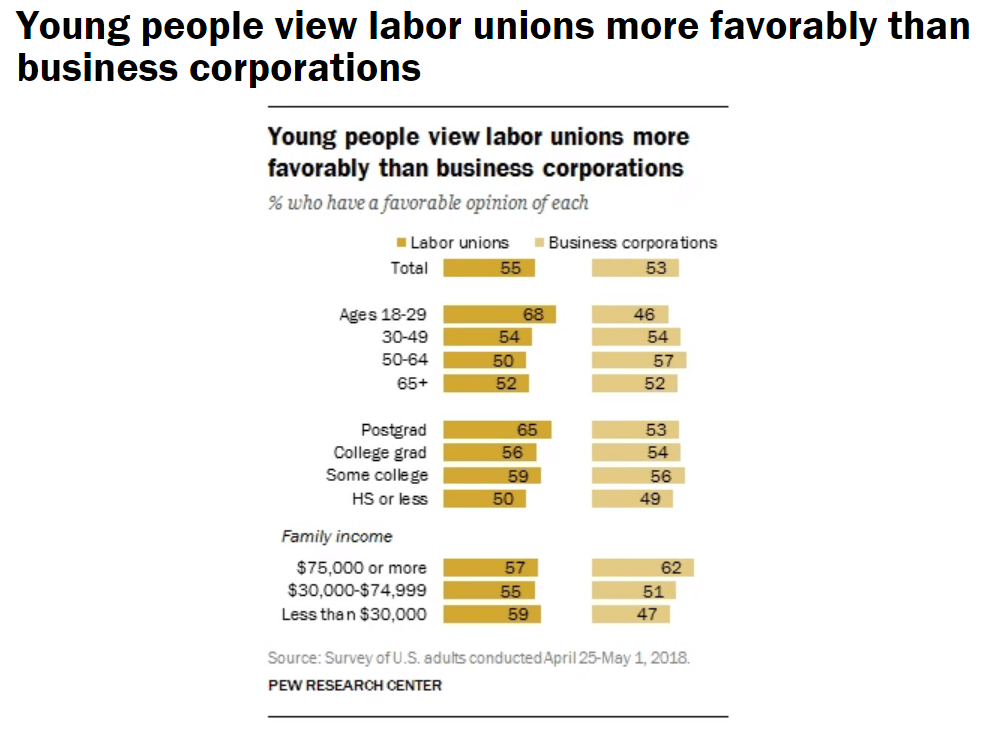

A recent Pew Research poll offers another, as shown below. Young people registered the strongest support for unions and the weakest support for corporations.

Of course, what millennials do rather than say is what counts. And millennials are now boosting the ranks of unions. Union membership grew in 2017 for the first time in years, by 262,000. And three in four of those new members was under 35. Figures for 2018 are not yet available, but given the strong and successful organizing work among education, health care, hotel, and restaurant workers, the positive trend is likely to continue.

Millennials are now the largest generation in the United States, having surpassed the baby boomers in 2015. Hopefully, self-interest will encourage them to play a leading role in building the movement necessary to transform the U.S. political-economy, improving working and living conditions for everyone.