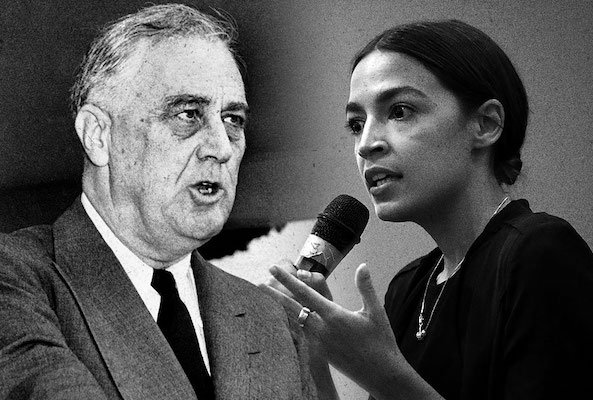

The New Deal has recently become a touchstone for many progressive efforts, illustrated by Bernie Sanders’ recent embrace of its aims and accomplishments and the popularity of calls for a Green New Deal. The reasons are not hard to understand. Once again, growing numbers of people have come to the conclusion that our problems are too big to be solved by individual or local efforts alone, that they are structural and thus innovative and transformative state-led actions will be needed to solve them.

The New Deal was indeed a big deal and, given contemporary conditions, it is not surprising that people are looking back to that period for inspiration and hope that meaningful change is possible. However, inspiration, while important, is not the same as seeking and drawing useful organizing and strategic lessons from a study of the dynamics of that period.

This is the first of a series of posts in which I will try to illuminate some of those lessons. In this first post I start with the importance of crisis as a motivator of change. What the experience of the Great Depression shows is that years of major economic decline and social devastation are not themselves sufficient to motivate business and government elites to pursue policies likely to threaten the status quo. It was only after three and a half years of organizing had also created a political crisis, that the government began taking halting steps at serious change, marked by the policies associated with the First New Deal. In terms of contemporary lessons, this history should serve to dispel any illusions that simply establishing the seriousness of our current multifaceted crisis will be enough to win elite consideration of a transformative Green New Deal.

The Great Depression

The U.S. economy expanded rapidly throughout the 1920s, a period dubbed the Roaring Twenties. It was a time of rapid technological change, business consolidation, and wealth concentration. It was also a decade when many traditional industries struggled, such as agriculture, textiles, coal, and shipbuilding, as did most of those who worked in them. Growth was increasingly sustained by consumer demand underpinned by stock market speculation and debt.

The economy suffered a major downturn in 1920-21, and then mild recessions in 1924 and 1927. And there were growing signs of the start of another recession in summer 1929, months before the October 1929 stock market collapse, which triggered the beginning of the Great Depression. The collapse quickly led to the unraveling of the U.S. economy.

The Dow Jones average dropped from 381 in September 1929 to forty-one at the start of 1932. Manufacturing output fell by roughly 40 percent between 1929 and 1933. The number of full-time workers at United States Steel went from 25,000 in 1929 to zero in 1933. Five thousand banks failed over the same period. Steve Frazer captured the extent and depth of the decline as follows:

In early 1933, thirty-six of forty key economic indicators had arrived at the lowest point they were to reach during the whole eleven grim years of the Great Depression.

The resulting crisis hit working people hard. Between 1930 and 1932, the number of unemployed grew from 3 million to 15 million, or approximately 25 percent of the workforce. The unemployment rate for those outside the agricultural sector was close to 37 percent. As Danny Lucia describes:

Workers who managed to hold onto their jobs faced increased exploitation and reduction in wages and hours, which made it harder for them to help out jobless family and friends. The social fabric of America was ripped by the crisis: One-quarter of children suffered malnutrition, birth rates dropped, suicide rates rose. Many families were torn apart. In New York City alone, 20,000 children were placed in institutions because their parents couldn’t support them. Homeless armies wandered the country on freight trains; one railroad official testified that the number of train-hoppers caught by his company ballooned from 14,000 in 1929 to 186,000 in 1931.

“Not altogether a bad thing”

Strikingly, despite the severity of the economic and social crisis, business leaders and the federal government were in no hurry to act. There was certainly no support for any meaningful federal relief effort. In fact, business leaders initially tended to downplay the seriousness of the crisis and were generally optimistic about a quick recovery.

As the authors of Who Built America (volume 2) noted:

when the business leaders who made up the National Economic League were asked in January 1930 what the country’s ‘paramount economic problems’ were, they listed first, ‘administration of justice,’ second, ‘Prohibition,” and third, ‘lawlessness.’ Unemployment was eighteenth on their list!

Some members of the Hoover administration tended to agree. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon thought the crisis was “not altogether a bad thing.” “People,” he argued, “will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people.”

President Hoover repeatedly stated that the economy was “on a sound and prosperous basis.” The solution to the crisis, he believed, was to be found in restoring business confidence and that was best achieved through maintaining a balanced budget. When it came to relief for those unemployed or in need, Hoover believed that the federal government’s main role was to encourage local government and private efforts, not initiate programs of its own.

At time of stock market crash, relief for the poor was primarily provided by private charities, which relied on donations from charitable and religious organizations. Only 8 states had any type of unemployment insurance. Not surprisingly, this system was inadequate to meet popular needs. As the authors of Who Built America explained:

by 1931 most local governments and many private agencies were running out of money for relief. Sometimes needy people were simply removed from the relief rolls. According to one survey, in 1932 only about one-quarter of the jobless were receiving aid. Many cities discriminated against nonwhites. In Dallas and Houston, African-Americans and Mexican-Americans were denied any assistances.

It was not until January 1932 that Congress made its first move to strengthen the economy, establishing the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to provide support to financial institutions, corporations, and railroads. Six months later, in July, it approved the Emergency Relief and Construction Act, which broadened the scope of the RFC, allowing it to provide loans to state and local governments for both public works and relief. However, the Act was structured in ways that undermined its effectiveness. For example, the $322 million allocated for public works could only be used for projects that would generate revenue sufficient to pay back the loans, such as toll bridges and public housing. The $300 million allocated for relief also had to be repaid. Already worried about debt, many local governments refused to apply for the funds.

Finally, as 1932 came to a close, some business leaders began considering the desirability of a significant federal recovery program, but only for business. Most of their suggestions were modeled on World War I programs and involved government-business partnerships designed to regulate and stabilize markets. There was still no interest in any program involving sustained and direct federal relief to the millions needing jobs, food, and housing.

By the time of Roosevelt’s inauguration in March 1933, the economy, as noted above, had fallen to its lowest point of the entire depression. Roosevelt had won the presidency promising “a new deal for the American people,” yet his first initiatives were very much in line with the policies of the previous administration. Two days after his inauguration he declared a national bank holiday, which shut down the entire banking system for four days and ended a month-long run on the banks. The “holiday” gave Congress time to approve a new law which empowered the Federal Reserve Board to supply unlimited currency to reopened banks, which reassured the public about the safety of their accounts.

Six days after his inauguration, Roosevelt, who had campaigned for the Presidency, in part, on a pledge to balance the federal budget, submitted legislation to Congress which would have cut $500 million from the $3.6 billion federal budget. He proposed eliminating government agencies, reducing the pay of civilian and military federal workers (including members of Congress), and slashing veterans’ benefits by 50 percent. Facing Congressional opposition, the final bill cut spending by “only” $243 million.

Lessons

It is striking that some 3 ½ years after the start of the Great Depression, despite the steep decline in economic activity and incredible pain and suffering felt by working people, business and government leaders were still not ready to support any serious federal program of economic restructuring or direct relief. That history certainly suggests that even a deep economic and social crisis cannot be counted on to encourage elites to explore policies that might upset existing structures of production or relations of power, an important insight for those hoping that recognition of the seriousness of our current environmental crisis might encourage business or government receptivity to new transformative policies.

Of course, we do know that in May 1933 Roosevelt finally began introducing relief and job creation programs as part of his First New Deal. And while many factors might have contributed to such a dramatic change in government policy, one of the most important was the growing movement of unemployed and their increasingly militant and collective action in defense of their interests. Their activism was a clear refutation of business and elite claims that prosperity was just around the corner. It also revealed a growing radical spark, as more and more people openly challenged the legitimacy of the police, courts, and other state institutions. As a result, what was an economic and social crisis also became a political crisis. As Adolf Berle, an important member of Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust,” wrote, “we may have anything on our hands from a recovery to a revolution.”

In Part II, I will discuss the rise and strategic orientation of the unemployment movement, highlighting the ways it was able to transform the political environment and thus encourage government experimentation. And I will attempt to draw out some of the lessons from this experience for our own contemporary movement building efforts.

The 1933 programs, although important for breaking new ground, were exceedingly modest. And, as I will discuss in a future post, it was only the rejuvenated labor movement that pushed Roosevelt to implement significantly more labor friendly policies in the Second New Deal starting in 1935. Another post will focus more directly on the development and range of New Deal policies in order to shed light on the forces driving state policy as well as the structural dynamics which tend to limit its progressive possibilities, topics of direct relevance to contemporary efforts to envision and advance a Green New Deal agenda.