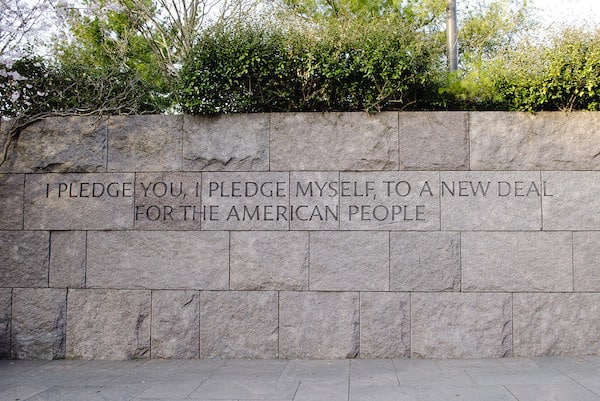

In Part I and Part II of this series on lessons to be learned from the New Deal I argued that despite the severity of the Great Depression, sustained organizing was required to transform the national political environment and force the federal government to accept direct responsibility for financing relief and job creation programs. In this post, I begin an examination of the evolution and aims of New Deal programs in order to highlight the complex and conflictual nature of a state-directed reform process.

The New Deal is often talked about as if it were a set of interconnected programs that were introduced at one moment in time to reinvigorate national economic activity and ameliorate the hardships faced by working people. Advocates for a Green New Deal, which calls for a new state-led “national, social, industrial, and economic mobilization” to confront our multiple interlocking problems, tend to reinforce this view of the New Deal. It is easy to understand why: state action is desperately needed, and pointing to a time in history when it appears that the state rose to the occasion, developing and implementing the programs necessary to solve a crisis, makes it easier for people to envision and support another major effort.

Unfortunately, this view misrepresents the experience of the New Deal. And, to the extent it influences our approach to shaping and winning a Green New Deal, it weakens our ability to successfully organize and promote the kind of state action we want.

The New Deal actually encompasses two different periods; the First New Deal was begun in 1933, the Second New Deal in 1935. In both periods, the programs designed to respond to working class concerns fell far short of popular demands. In fact, it was continued mass organizing, spearheaded by an increasingly unified unemployed movement and an invigorated trade union movement, that pushed the Roosevelt administration to initiate its Second New Deal, which included new and significantly more progressive initiatives.

Unfortunately, as those social movements lost energy and vision in the years that followed, pressure on the state for further change largely abated, leaving the final reforms won compromised and vulnerable to future attack. The lesson from this history for those advocating for a Green New Deal is clear: winning a Green New Deal requires, in addition to carefully constructed policy demands, an approach to movement building that prepares people for a long struggle to overcome expected state efforts to resist the needed transformative changes.

The First New Deal

Roosevelt’s initial policies were largely consistent with those of the previous Hoover administration. Like Hoover, he sought to stabilize the banking system and balance the budget. On his first day in office Roosevelt declared a national bank “holiday,” dismissing Congressional sentiment for bank nationalization. He then rushed through a new law, the Emergency Banking Act, which gave the Comptroller of the Currency, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the Federal Reserve new powers to ensure that reopened banks would remain financially secure.

On his sixth day in office, he requested that Congress cut $500 million from the $3.6 billion federal budget, eliminate government agencies, reduce the salaries of civilian and military federal workers, and slash veterans’ benefits by 50 percent. Congressional resistance led to spending cuts of “only” $243 million.

Roosevelt remained committed, against the advice of many of his most trusted advisers, to balanced budget policies for most of the decade. While his administration did boost government spending to nearly double the levels of the Hoover administration, it also collected sufficient taxes to keep deficits low. It wasn’t until 1938 that Roosevelt proposed a Keynesian-style deficit spending plan.

At the same time, facing escalating demands for action from the unemployed as well as many elected city leaders, Roosevelt also knew that the status quo was politically untenable. And, in an effort to halt the deepening depression and growing militancy of working people, he pursued a dizzying array of initiatives, most within his first 100 days in office. The great majority were aimed at stabilizing or reforming markets, which Roosevelt believed was the best way to restore business confidence, investment, and growth. This emphasis is clear from the following list of some of his most important initiatives.

- The Agricultural Adjustment Act (May 1933). The act sought to boost the prices of agricultural goods. The government bought livestock and paid subsidies to farmers in exchange for reduced planting. It also created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration to manage the payment of subsidies.

- The Securities Act of 1933 (May 1933). The act sought to restore confidence in the stock market by requiring that securities issuers disclose all information necessary for investors to be able to make informed investment decisions.

- The Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 (June 1933). The act sought to stabilize the finance industry and housing industry by providing mortgage assistance to homeowners. It created the Home Owners Loan Corporation which was authorized to issue bonds and loans to help homeowners in financial difficulties pay their mortgages, back taxes, and insurance.

- The Banking Act of 1933 (June 1933). The act separated commercial and investment banking and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to insure bank deposits, curb bank runs, and reduce bank failures.

- Farm Credit Act (June 1933). The act established the Farm Credit System as a group of cooperative lending institutions to provide low cost loans to farmers.

- National Industrial Recovery Act (June 1933). Title I of the act suspended anti-trust laws and required companies to write industrywide codes of fair competition that included wage and price fixing, the establishment of production quotas, and restrictions on market entry. It also gave workers the right to organize unions, although without legal protection. Title I also created the National Recovery Administration to encourage business compliance. The Supreme Court ruled the suspension of anti-trust laws unconstitutional in 1935. Title II, which established the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works or Public Works Administration, is discussed below.

Roosevelt also pursued several initiatives in response to working class demands for jobs and a humane system of relief. These include:

- The Emergency Conservation Work Act (March 1933). The act created the Civilian Conservation Corps which employed jobless young men to work in the nation’s forests and parks, planting trees, reducing erosion, and fighting fires.

- The Federal Emergency Relief Act of 1933 (May 1933). The act created the Federal Emergency Relief Administration to provide work and cash relief for the unemployed.

- The Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works or Public Works Administration (June 1933). Established under Title II of the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Public Works Administration was a federally funded public works program that financed private construction of major public projects such as dams, bridges, hospitals, and schools.

- The Civil Works Administration (November 1933). Established by executive order, the Civil Works Administration was a short-lived jobs program that employed jobless workers at mostly manual-labor construction jobs.

This is without doubt an impressive record of accomplishments, and it doesn’t include other noteworthy actions, such as the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the ending of prohibition, and the removal of the U.S. from the gold standard. Yet, when looked at from the point of view of working people, this First New Deal was sadly lacking.

Roosevelt’s pursuit of market reform rather than deficit spending meant a slow recovery from the depths of the recession. In fact, John Maynard Keynes wrote Roosevelt a public letter in December 1933, pointing out that the Roosevelt administration appeared more concerned with reform than recovery or, to be charitable, was confusing the former with the latter. Primary attention, he argued, should be on recovery, and that required greater government spending financed by loans to increase national purchasing power.

Roosevelt also refused to address one of the unemployed movement’s major policy demands: the establishment of a federal unemployment insurance fund financed by taxes on the wealthy. Finally, as we see next, even the New Deal’s early job creation and relief initiatives were deliberately designed in ways that limited their ability to meaningfully address their targeted social concerns.

First New Deal employment and relief programs

The Roosevelt administration’s first direct response to the country’s massive unemployment was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Its enrollees, as Roosevelt explained, were to be “used in complex work, not interfering with normal employment and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects.” The project was important for establishing a new level of federal responsibility, as employer of last resort, for boosting employment. Over its nine-year lifespan, its participants built thousands of miles of hiking trails, planted millions of trees, and fought hundreds of forest fires.

However, the program was far from meeting the needs of the tens of million jobless and their dependents. Participation in the program was limited to unmarried male citizens, 18 to 25 years of age, whose families were on local relief, and who were able to pass a physical exam. By law, maximum enrollment in the program was limited to 300,000.

Moreover, although the CCC provided its participants with shelter, clothing, and food, the wages it paid, $30 a month ($25 of which had to be sent home to their families), were low. And, while white and black were supposed to be housed together in the CCC camps where participants lived under Army supervision, many of the camps were segregated, with whites given preference for the best jobs.

Two months later, the Roosevelt administration launched the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the first program of direct federal financing of relief. Under the Hoover administration, the federal government had restricted its support of state relief efforts to the offer of loans. Because of the precariousness of their own financial situation, many states were unable to take on new debt, and were thus left with no choice but to curtail their relief efforts.

FERA, in contrast, offered grants as well as loans, providing approximately $3 billion in grants over its 2 ½ year lifespan. The grants allowed state and local governments to employ people who were on relief rolls to work on a variety of public projects in agriculture, the arts, construction and education. FERA grants supported the employment of over 20 million people, or about 16 percent of the total population of the United States.

However, the program suffered from a number of shortcomings. FERA provided funds to the states on a matching basis, with states required to contribute three dollars for every federal dollar. This restriction meant that a number of states, struggling with budget shortfalls, either refused to apply for FERA grants or kept their requests small.

Also problematic was the program’s requirement that participants be on state relief rolls. This meant that only one person in a family was eligible for FERA work. And the amount of pay or relief was determined by a social worker’s evaluation of the extent of the family’s financial need. Many states had extremely low standards of necessity, resulting in either low wages or inadequate relief payments which could sometimes be limited to coupons exchangeable only for food items on an approved list.

Finally, FERA was not directly involved in the administration and oversight of the projects it funded. This meant that compensation for work and working conditions differed across states. It also meant that in many states, white males were given preferential treatment.

A month later, the Public Works Administration (PWA) was created as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act. The PWA was a federal public works program that financed private construction of major long-term public projects such as dams, bridges, hospitals, and schools. Administrators at PWA headquarters planned the projects and then gave funds to appropriate federal agencies to enable them to help state and local governments finance the work. The PWA played no role in hiring or production; private construction companies carried out the work, hiring workers on the open market.

The program lasted for six years, spent $6 billion, and helped finance a number of important infrastructure projects. It also gave federal administrators valuable public policy planning experience, which was put to good use during World War II. However, as was the case with FERA, PWA projects required matching contributions from state and local governments, and given their financial constraints, the program never spent as much money as was budgeted.

These programs paint a picture of a serious but limited effort on the part of the Roosevelt administration to help workers weather the crisis. In particular, the requirement that states match federal contributions to receive FERA and PWA funds greatly limited their reach. And, the participant restrictions attached to both the CCC and FERA meant that program benefits were far from adequate. Moreover, because all of these were new programs, it often took time for administrators to get funds flowing, projects developed, participants chosen, and benefits distributed. Thus, despite a flurry of activity, millions of workers and their families remained in desperate conditions with winter approaching.

Pressed to do more, the Roosevelt administration launched its final First New Deal jobs program in November 1933, the Civil Works Administration (CWA), under the umbrella of FERA. It was designed to be a short-term program, and it lasted only 6 months, with most employment creation ending after 4 months. The jobs created were primarily low-skilled construction jobs, improving or constructing roads, schools, parks, airports, and bridges. The CWA gave jobs to some 4 million people.

This was a dramatically different program from those discussed above. Most importantly, employment was not limited to those on relief, greatly enlarging the number of unemployed who could participate. At the end of Hoover’s term in office, only one unemployed person out of four was on a relief roll. It also meant that participants would not be subject to the relief system’s humiliating means tests or have their wages tied to their family’s “estimated budgetary deficit.” Also significant was the fact that although many of the jobs were inherited from current relief projects, CWA administrators made a real effort to employ their workers in new projects designed to be of value to the community.

For all of these reasons, jobless workers flocked to the program, seeking an opportunity to do, in the words of the time, “real work for a real wage.” As Harry Hopkins, the program’s chief administrator, summed up in a talk shortly after the program’s termination:

When we started Civil Works we said we were going to put four million men to work. How many do you suppose applied for those four million jobs? About ten million. Now I don’t say there were ten million people out of work, but ten million people walked up to a window and stood in line, many of them all night, asking for a job that paid them somewhere between seven and eighteen dollars a week.

In point of fact, there were some fifteen million people unemployed. And as the demand for CWA jobs became clear, Roosevelt moved to end the program. As Jeff Singleton describes:

In early January Hopkins told Roosevelt that CWA would run out of funds sooner than expected. According to one account, Roosevelt “blew up” and demanded that Hopkins begin phasing out the program immediately. On January 18 Hopkins ordered weekly wages cut (through a reduction in hours worked) and hinted that the program would be terminated at the beginning of March. The cutback, coming at a time when the program had just reached its promised quota, generated a storm of protest and a movement in Congress to continue CWA through the spring of 1934. These pressures helped the New Deal secure a new emergency relief appropriation of $950 million, but the CWA was phased out in March and April.

Lessons

The First New Deal did represent an important change in the economic role of the federal government. In particular, the Roosevelt administration broke new ground in acknowledging federal responsibility for job creation and relief. Yet, the record of the First New Deal also makes clear that the Roosevelt administration was reluctant to embrace the transformative role that many now attribute to it.

As Keynes pointed out, Roosevelt’s primary concern in the first years of his administration was achieving market stability through market reform, not a larger financial stake in the economy to speed recovery. In fact, in some cases, his initiatives gave private corporations even greater control over market activity.

The Roosevelt administration response to worker demands for jobs and a more humane system of welfare was also far from transformative. Determined to place limits on federal spending, its major initiatives required substantial participation from struggling state governments. They also did little to challenge the punitive and inadequate relief systems operated by state governments. The one exception was the CWA, which mandated wage-paying federally directed employment. And that was the one program, despite its popularity, that was quickly terminated.

Of course, there was a Second New Deal, which included a number of important and more progressive initiatives, including the Works Progress Administration, the Social Security Act, and the National Labor Relations Act. However, as I will discuss in the next post in this series, this Second New Deal was largely undertaken in response to the growing strength of the unemployed movement and workplace labor militancy. And as we shall see, even these initiatives fell short of what many working people demanded.

One lesson to be learned from this history for those advocating a Green New Deal is that major policy transformations do not come ready made, or emerge fully developed. Even during a period of exceptional crisis, the Roosevelt administration was hesitant to pursue truly radical experiments. And the evolution of its policy owed far more to political pressure than the maturation of its administrative capacities or a new found determination to experiment.

If we hope to win a Green New Deal we will have to build a movement that is not only powerful enough to push the federal government to take on new responsibilities with new capacities, but also has the political maturity required to appreciate the contested nature of state policy and the vision necessary to sustain its forward march.