Those living in the U.S. are encouraged to think that they live in the best country in the world with little to learn from the experiences of working people in other countries. This sense is reinforced by the fact that the mainstream media generally discusses U.S. problems without reference to developments or trends in other developed capitalist countries.

Here is one example: hours of work. It is a common complaint that Americans work too many hours. What is rarely noted, as Ryan Cooper points out in his study titled The Leisure Agenda, is that “Americans work far, far more than their counterparts in peer European nations.”

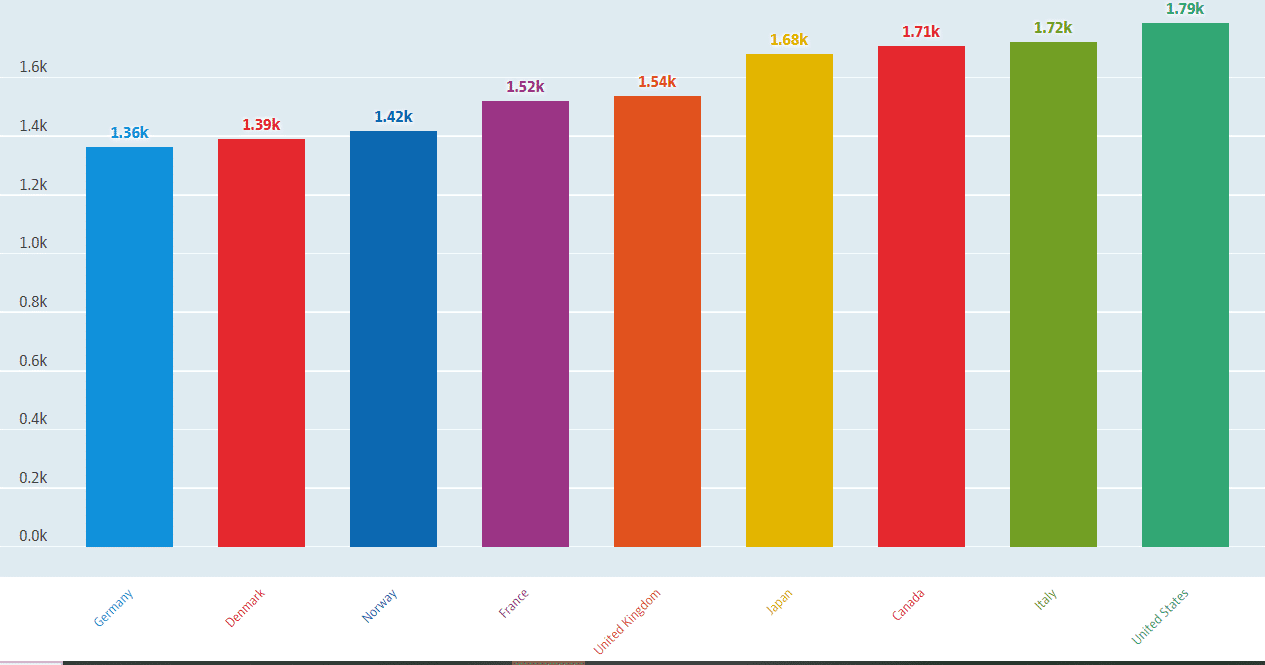

The figure below, based on OECD reported data for the year 2018, shows just how much more. The average U.S. worker works roughly 110 hours a year more than the average Japanese worker, or some 2.6 weeks more; about 265 hours a year more than the average French worker, or some 6.6 weeks more; and 420 hours more than the average German worker, or some 10.5 weeks.

The OECD defines average annual hours worked per employed person as:

the total number of hours actually worked per year divided by the average number of people in employment per year. Actual hours worked include regular work hours of full-time, part-time and part-year workers, paid and unpaid overtime, hours worked in additional jobs, and exclude time not worked because of public holidays, annual paid leave, own illness, injury and temporary disability, maternity leave, parental leave, schooling or training, slack work for technical or economic reasons, strike or labor dispute, bad weather, compensation leave and other reasons. The data cover employees and self-employed workers.

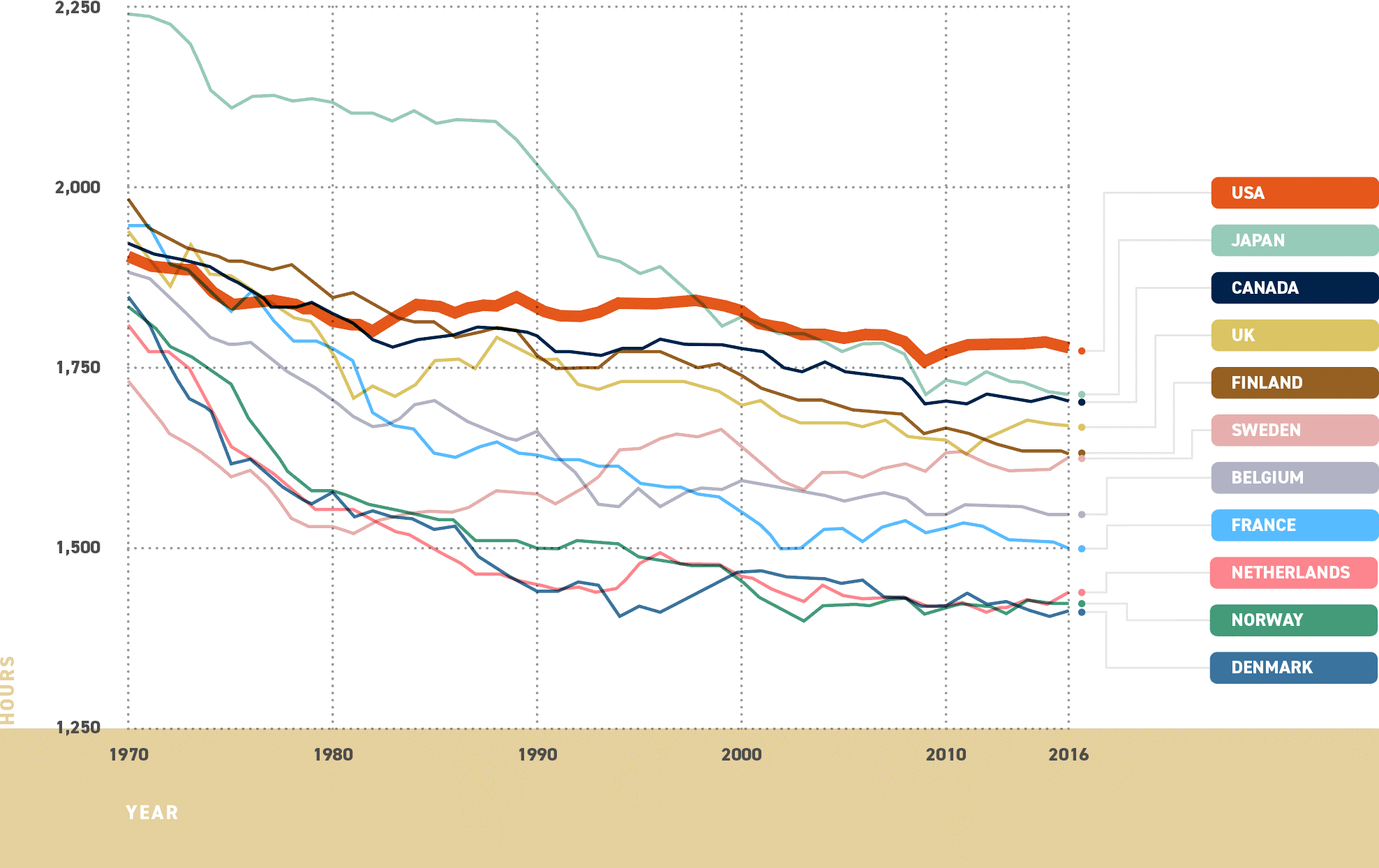

The trend in average annual hours of work in the U.S. and other developed capitalist countries highlights just how far outside the mainstream the U.S. labor experience is. The following figure, again based on OECD data, is taken from Cooper’s study. As he summarizes:

As most nations have gotten richer, their average worker has worked fewer hours. But this is not true of the United States. As shown [below], among wealthy OECD nations with data going back that far, the U.S. was in the middle of the pack among rich nations in 1970. Now, it works the most out of any in this cohort.

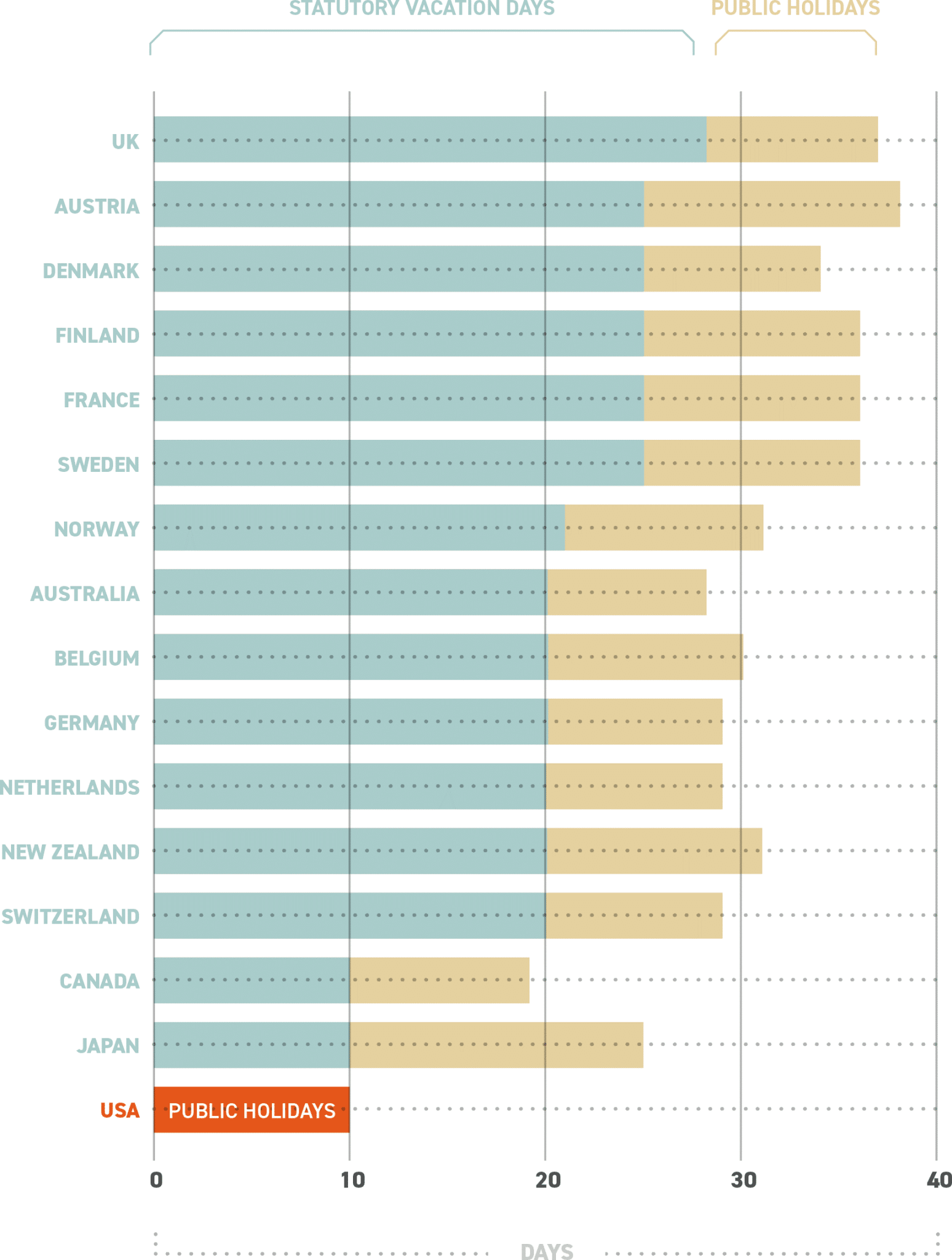

One reason for the higher average hours of work in the U.S. is that it is the only major OECD country that does not provide a federal statutory minimum annual leave entitlement to its workers, as illustrated in the following figure which is also from Cooper’s study.

The annual U.S. work hours presented above is for the average worker, which means that it includes the work experience of people who are forced to work extremely long hours as well as those who cannot find full-time employment. In both cases, the U.S. employment situation is a major contributor to the stress, poor health, and weakening community ties experienced by growing numbers of workers.

The lower average annual hours of work in other OECD countries does not mean that workers in those countries don’t have their own challenges, especially as many now confront governments that seek to undermine their past gains. At the same time, it does demonstrate that there is plenty of room for improvement in the United States.

In other countries a reduction in work hours and paid annual leave entitlements were won through aggressive workplace struggle and political pressure on governments. There is, of course, a long history of struggle for a shorter workday in the US, which came to be symbolized by May Day demonstrations and strike actions, and deserves renewed attention. It is also worth remembering that activists in that struggle were well aware that achieving a shorter work week was critical to securing for workers the time and energy needed to build a powerful working class movement for social transformation.