Let’s give credit where it’s due: After experiencing decades of neoliberal austerity and serving for nearly as long as pawns in tiresome culture wars, public higher education workers know all too well how the money works on our campuses and in our states. Students and alumni are the major sources of revenue; graduate workers and adjuncts teach the majority of courses for far lower pay than their tenure-track counterparts; state and federal governments offer little to no meaningful financial support; and arts and humanities departments are always first to the budgetary chopping block. Substantive gains in quality-of-life on campus, meanwhile, go first to the business and engineering schools, while athletic coaches, administrators, and academic celebrities are some of the only figures on campus who may expect to get (way) ahead financially under the current system. None of this is news for campus workers, and very few of us are now shocked to see disparities widen and inequalities deepen in our workplaces under pressure from the COVID-19 depression.

For these reasons, public higher education workers in the age of coronavirus do not need a crash course in corporate finance or austerity politics, as corporate consultant Allison Vaillancourt called for in her recent column for The Chronicle of Higher Education, titled “What if everyone on campus understood the money?” What we need instead are concrete and actionable proposals to secure and improve our immediate material conditions and remake our industry on more equitable and just foundations in the near term. We need, to paraphrase a recent article by Astra Taylor, a reparative way forward for public higher education that remediates past harms while ensuring a more prosperous and inclusive future for students and workers across the entire system.

Our contribution, developed in several outlets over the last six months, envisions a future for U.S. public higher education motivated by a radical variation on Vaillancourt’s provocative prompt: What if everyone on campus understood money?

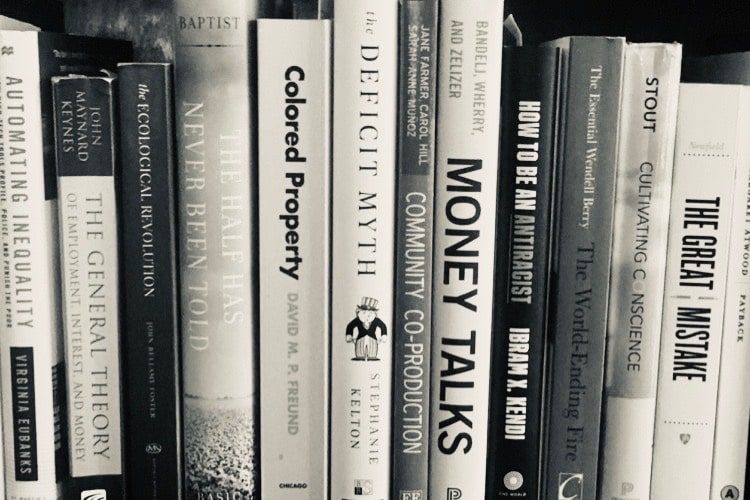

Having endured neoliberalism’s decades-long assault on higher education, many campus workers and administrators have come to know money intimately as a scarce and elusive object, or as something that can be gotten only at the expense of students and taxpayers. Economist Stephanie Kelton makes clear in her New York Times bestseller The Deficit Myth, however, that money is none of those things. As a legal institution and system for public provisioning, money is in fact no object. It is instead the symbolic representation of an expansive reserve of public credit, the uses of which are limited primarily by the political economic imaginations and normative preferences of a governing body and its constituents.

As Kelton and other scholars in the school of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have thoroughly documented, the lesson that money is far more than some physically delimited “thing” is one that has been learned and unlearned repeatedly throughout U.S. political history. Given the recent uptake of the MMT perspective by prominent progressive leaders like Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as well as the incorporation of MMT insights into popular proposals for the abolition of student debt and the Green New Deal, it appears that now–in the midst of numerous economic and political crises–is the perfect time to leverage the lessons of MMT to reactivate what sociologist Jakob Feinig has called “money politics” on our college and university campuses.

To that end, we offer a not-so modest proposal: In order to abate and overcome the myriad disasters resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, public colleges and universities should embrace their broad authority as credit-issuing and depository institutions to administer their own digital credit systems. Credit will circulate as a currency that we call the Uni. Unis will be immediately receivable as payment for all debts owed to the issuing college or university, including tuition, fees, rents, and meal plans. Far from a fly-by-night company scrip, the Uni builds symbiotic agreements with host cities and counties. While universities can use Unis to pay currently exempt property taxes to cash-starved local governments, the same municipalities can accept Uni payments from regional businesses and residents to widen the circuit of receivability from College Avenue to Main Street.

With this, the Uni positions public colleges and universities as leaders in the inevitable transition to a new federal digital payments system. It combines cutting edge financial technology, or fintech, with an MMT model of credit creation and injects much needed liquidity into our public infrastructures and political subdivisions. As such, the Uni ameliorates two pressing monetary system issues. First, it makes the Uni a fintech first responder capable of democratically addressing local cash-flow crises. Second, as an open public digital infrastructure, the Uni invites collaboration with federal regulatory bodies to test innovative rules and protections against exploitative fintech actors and systemic instability. These design features complement the existing experimental efforts of the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) while addressing shortcomings in the MLF’s initial roll out. In sum, the Uni’s capacity to contribute to a more dynamic and resilient monetary architecture opens the door for permanent Fed accommodation, recognizing universities and colleges as public finance franchisees.

What reads as a moonshot proposal on first pass becomes an obvious maneuver after cursory review of the history of U.S. money politics in times of great transformation and crisis. The Great Depression, for example, inspired numerous successful experiments developing sophisticated local public credit systems (i.e., complementary currencies) in order to keep people fed and housed at a time when money, food, and housing were otherwise thought to be scarce commodities.

Neither have such radical experiments in apportioning public credit been limited to the local level, or been put to purely salutary ends. As historian David Freund has shown, the U.S. federal government mobilized its capacious public credit system in midcentury to both fashion and guarantee the long-term prospects of an expanding white middle-class. That prosperity was granted to some but not all was not, Freund shows, the result of natural monetary scarcity. It was rather a direct consequence of the federal government deciding to channel its fiscal authority to fortify and defend a fundamentally racist housing system. Underwriting racist histories of redlining, prosperity for some but not all was only ever a policy choice.

Today, the inherently political nature of our public monetary system is difficult to ignore. As higher ed workers wait restively for state and federal legislators to take meaningful action on their behalf, multinational corporations are enjoying record-breaking profits and building predatory digital credit systems of their own. From this vantage, recent furloughs and firings across the public higher education system were clearly not inevitable, but substantially the result of a series of decisions taken by the House and Senate to deny our institutions the same financial boosts granted to massive private investment companies like Blackstone. Should campus workers continue to wait for adequate financial support from deficit-averse state and federal legislatures, then likely only more pink slips and red ink await.

The Uni charts an alternate path forward, one that circumvents passive legislators in order to stake new claims on the full faith and credit of our constitutional collectivity. Local Uni credit systems will immediately provide aid to those who most urgently need it: students, staff, and instructors who cannot pay tuition, make rent, or afford to eat well; departments suffering declines in enrollment as they struggle to transition to online classrooms; frontline community workers; desperate local businesses; strained municipalities; and even Presidents and Deans, Commissioners and Mayors who might rather not fire or furlough a substantial portion of their workforce in the middle of a global pandemic and economic depression.

Make no mistake: now is a dire and, by all accounts, pivotal moment for U.S. colleges and universities. While commentators like Vaillancourt wish to use the present crisis to complete the corporate streamlining of higher ed, a minoritarian right-wing movement led by Betsy DeVos aims to dismantle our institutions in service of an anti-humanist and anti-science agenda. As grim as these prospects appear, however, history has shown time and again that monetary experimentation can function not only as a powerful stopgap against budget shortfalls, but also as a strategic bulwark against forces of reaction.

By repositioning public colleges and universities as avowed and robust hubs of credit creation and distribution, the Uni promises to restore money as a topos for political engagement and shared governance in higher education. Precisely what gets funded, and why, will become hotly contested issues on campuses where such questions had long since been definitively answered by de facto austerity and politically appointed and typically partisan board members.

Perhaps the most basic and important takeaway from the Uni for the present crisis is this: Ultimately, it is the public credit system that determines the financial viability of our institutions, not the ebb and flow of revenues. Returns can always run dry. Yet credit remains inexhaustible because, as Kelton reminds us, it is no object. Money is, in truth, a social relation that can always be extended and reorganized. Therefore, the real threat to our public institutions during the coronavirus health emergency is not a short-term lack of income. It is a dearth of political imagination. The Uni, by contrast, refuses scarcity politics and seizes public credit for far-reaching democratic ends.