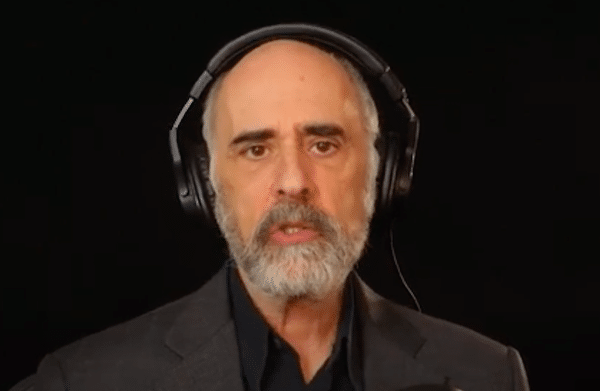

Peter Carter of the Climate Emergency Institute says “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050 and targeting 2 degrees warming are a recipe for runaway climate catastrophe. On theAnalysis.news podcast with Paul Jay.

Transcript

Paul Jay: Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news podcast. Please don’t forget we are doing a fundraising campaign. One of our members has put up a $10,000 matching grant: for every dollar we raise, he’ll match it. If you give a one-time donation, he’ll match that. If you initiate a monthly donation, he’ll match that amount for the year. If you’re already doing a monthly donation and increase it, he’ll match the increase for a year. And I hope you do.

President-elect Biden has announced that John Kerry will be his climate czar to lead what Biden calls an aggressive plan. Kerry says he’ll do what’s necessary. The plan will commit to what scientists say is the urgency of the situation. In Canada, The Toronto Star reports that the Trudeau government is introducing what’s being called climate accountability legislation. This creates a legal framework that requires the federal government to prepare plans to slash emission targets set every five years beginning in 2030. The ultimate goal is to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, whether they are eliminated or offset by nature or carbon-capture technology.

Well, neither the Biden nor Trudeau climate plans reach the targets scientists say are necessary. Let’s start with just how urgent it is, because as devastating as the Covid pandemic is, we will get past it. We won’t get past catastrophic climate crisis. And that’s where we are headed at a speed that keep surprising many scientists.

Now joining us is Peter Carter. He’s a retired family physician who practiced medicine in England and then on both coasts of Canada–Newfoundland and British Columbia–for almost 40 years. He’s founding director of CAPE, the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment and, more recently, a founder of the Climate Emergency Institute. Peter has been following global warming and climate change research since 1988. He was an expert reviewer for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change–that’s the IPCC–for both their fifth climate change assessment in 2014 and its 2018 special report, Global Warming of 1.5C. Also, in 2018, Peter published Unprecedented Crime: Climate Change Denial and Game Changers for Survival, which he co-authored with Elizabeth Woodsworth.

Thanks for joining us, Peter.

Peter Carter: Thank you very much. Thank you, Paul. It’s good to be here with you.

Paul Jay: So, there’s an economist named Nordhaus whom I mentioned on a previous interview I did with Bob Pollin. He won the Nobel Prize in 2018. And he says, yes, the climate crisis is real, but we can hit four degrees above the preindustrial average sometime this century, at which we can then stabilize. That’s somewhat less than urgent. Now, this guy got the Nobel Prize in economics specifically for the work he does on climate. Now, if this guy is influential and if he’s informing Biden, Trudeau, and the various elites that have real power in our society, then they think Nordhaus is right and we’ve got lots of time to figure this out. They probably they think that there’ll be some magical technology that’s going to show up over the next hundred years. So, why worry? And even this Toronto Star report is talking about figuring out carbon capture.

So, first of all, how urgent is climate change. And what do you think of Nordhaus’ timeframe?

Peter Carter: Mr. Nordhaus is a well-known economist. He is very well-known in the climate change community because decades ago he is reputed to be one of the main people who urged governments to set a two-degree C[elsius] permanent limit of global temperature increase over the preindustrial average.

Paul Jay: Let me just jump in for people. That’s two degrees average global temperature above pre-Industrial Revolution average global temperature.

Peter Carter: Yeah, it’s a lousy metric. I mean, you know, you really have to be in climate change science for a long time to even appreciate what it means. So, it was a terrible metric to choose. And it’s one of the things that has totally confused people rather than informing them. But that made him famous and well-known. And recently he’s published a paper. I’d have to go back and check on it; the first time I read it, I couldn’t even believe it. In this paper. He said that three degrees C, I believe, he said, is the optimum temperature increase for climate.

Paul Jay: No, four. I saw the paper. It’s four degrees.

Peter Carter: Oh, my god.

Paul Jay:He says that the world over the next hundred years, essentially, can gradually get to four and then the optimum temperature will be four degrees above the preindustrial average.

Peter Carter: We’ll never see four degrees. Humanity will never see three degrees. We will be long gone. That is an insane, ridiculous, horrible thing to say. Two degrees, which he supported, was adopted by the EU in 1996 as a compromise. The scientists were saying at that time that the limit should be 1.5 degrees C. Way back in the 1990s. Two degrees C, I want to point out, is called an equilibrium limit. We were going to limit warming to two degrees C forever. We were never, ever going to go above two degrees C.

One of the reasons why the EU picked that I remember at the time, was that they said anything higher, would be catastrophic to agriculture, catastrophic to ecosystems. But they also said they picked two degrees C because it would not exclude runaway [warming]. They use the term “runaway.” It would minimize the risk of runaway. Well, we know now that at two degrees C, we trigger runaway.

Paul Jay: What is “runaway?”

Peter Carter:“Runaway” is not really a term that is favored by the climate scientists, but it’s a term that the environmentalists and the NGOs have used for a long, long time. And it’s a very good term because what it means is that amplifying feedbacks in the earth and climate system kick in whereby, for example, the planet emits more greenhouse gases of its own accord. The easiest feedback to understand is forest fires increased by climate change which introduces a lot more carbon dioxide up in the atmosphere, also some methane and black carbon. So, you get all the main global warming greenhouse gases emitted if you have more forest fires. That’s called an amplifying feedback because it amplifies what our industrial civilization has already been doing.

There are many, many sources of amplifying feedback, and they’re enormous. Most of the sources, and most of the enormous sources, are in the Arctic but we’ve also got, for instance, the Amazon, which would be a massive source if the Amazon collapsed, which is happening already, and went through die-back, as the experts called it, then anything that we could try to do would be useless. We would be completely powerless to influence the climate system at all.

Paul Jay: You’re saying this happens at two degrees. But my understanding from some of the leading IPCC climate scientists is that if every country that agreed actually did what they agreed to in the Paris Accords, we’d still be hitting two degrees by 2050. The Paris accord doesn’t stop two degrees. And you’re saying if we hit two degrees, it’s too late.

Peter Carter: Oh, two degrees is too late. There are lots of climate experts saying in public statements and papers that it may well be too late now, and we’re at 1.1, 1.2 degrees C, right? And look at all the catastrophic events that we’ve had already. Two degrees C will definitely trigger runaway warming.

There was a good paper that got quite a lot of publicity the year before last. it brought attention to what it called a hothouse earth situation, which is another term for runaway. It’s a scientific term. And if you examine that paper carefully, which I did because it’s a most important paper, you’ll see that all the triggers (that paper had about eight) happen at two degrees C. So, the EU decades ago saying that two degrees C would minimize but not exclude the risk of runaway is absolutely right.

There are two main huge survival complications of global warming, considering humanity alone. One is agriculture, right? We have fabulously successful agriculture, especially in the United States, but also in Europe and now in China, which is producing more food than anybody else. Our agriculture is amazingly successful, but it depends solely on the stable climate that we’ve had for the past ten or eleven thousand years, which is precisely how agriculture could have been invented and developed in many sites around the world. It’s obvious it was climate stability which allowed human beings to do agriculture, which our civilization is totally and absolutely dependent on. There are multiple adverse effects of climate change on agriculture. Many, many, many adverse effects. And it’s really just common sense that if you get to a degree of heating, a degree of fires, a degree of drought alone, then you’re going to collapse agriculture because the plants can’t tolerate a certain level of temperature, a certain heat.

In actual fact, they have a tipping point. They collapse at about 30 degrees C. So, number one, we always should have, but now we have to give it everything, we’ve got, tried to protect agriculture. I watched a video by Paul Erlich from Stanford recently. He was very good; he started on agricultural catastrophe right away. Agriculture is something that I’ve been very much interested in and involved in and consulting in. And it is the absolute key for our survival. And it is the most important aspect at issue for humanity with respect to climate change.

Now, the other big issue–a big, horrible impact of climate change–is what’s called runaway. And that will wipe out just about all life from the planet. This is why the secretary general of the United Nations, António Guterres, in 2018 at a world summit made a public statement that climate change is simply the biggest existential threat to life on the planet. And he said particularly to humanity. That’s what he was talking about. And at the at the IPCC Conference of the Parties, the COP, in Poland–every year we have a COP under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This one was in Poland. He made an opening statement at that one: if we don’t put our global emissions into decline immediately, then we are open to the risk of runaway.

Now, he’s a great, great spokesperson for us and a great secretary general. He, of course, can’t make those statements without the backing of the top scientists in the world, even if the top scientists in the world aren’t saying it. So, runaway is it. It’s game over for everything. It’s a completely different planet, a planet which is hot, hot, hot and heating up, and not like the planet has heated up in the past, millions of years ago, but it’s heated up by our emissions at the fastest rate that it’s ever been.

Paul Jay: Is there a debate among scientists about whether two degrees triggers runaway? Like, if we’re heading two degrees in 2050, which is what a lot of scientists are saying, does that mean we’re triggering runaway at that point?

Peter Carter: Yeah, the scientific way to look at this is to say, what are we risking? OK, because the scientists say, well, we can’t be sure. You know, our computer models aren’t yet programmed for this sort of thing. For public communication, if we look at risk–which, of course, all the scientists should be; they’re actually not, with some notable exceptions–if we look at the risk, our risk of triggering runaway warming at two degrees C is absolutely enormous.

And there have been a couple of risk papers that have been published saying that. The 1.5 degrees C report by the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which was published in 2018 is still their best report ever. It made the risk abundantly clear. This is why, all of a sudden after the 1.5 degrees C report, the public at large and governments suddenly said, “Oh, my God. Yes, we’re in a climate emergency.” And of course, it was great for me. I’ve been trying to convince people of this for more than ten years. It’s a bit late in the day. But at least we now have this general acknowledgement right around the world that, yes, we’re in a climate emergency. And the big reasons for that are huge risk to our agriculture and an enormous risk of runaway. It’s a zero-tolerance risk in terms of economics. You have to be more than 100 percent certain that you’re going to avoid runaway.

Paul Jay: The targets that are being talked about now is zero net-carbon emissions by 2050. I think the Chinese have said they’re going to hit it by, I’m not sure, 2060, 2065. If those targets are hit, is that enough?

Peter Carter: “Net carbon emissions” allows us to enter the age of climate change delusion. It’s a relatively new term. Since 1990, we have had IPCC assessments and hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of scientists’ papers published which have always talked in terms of actual emissions. And they have always said that actual emissions have to be reduced massively and rapidly. They said this very clearly in the 1990 assessment. The IPCC assessment in 2014, the fifth assessment, said that we have to get all our main greenhouse gas emissions down to near zero. And if you look very deeply at the 1.5C report, you’ll see that they have that in there. So, “net zero” is not science. “Net zero” as it’s being interpreted is science fiction.

Paul Jay: And that’s because net zero includes carbon capture, which is a totally unproven technology anyway?

Peter Carter: Well, yes, it is, Paul. The big problem with net zero is there’s all kinds of definitions of it. And when you’re talking about the future of humanity and the future of life on Earth, you have to be definite in what you’re talking about. This is abundantly clear. In order to make policy makers understand, you have to be definite. In order to make the public understand–and the public wants to understand–you have to be definite. Net zero can actually mean pretty well anything. The common definition that is out there in the science centers like MIT is, countries will get their emissions down as far as possible and then they will remove the CO2 in the atmosphere that’s left over.

It’s absolutely crazy. It contradicts all the climate science that we’ve had for the past twenty, twenty-five years, which is very definite. Emissions have to be dropped. In 1990, it was 80 percent, like, in a matter of years. And now, of course, because we’ve got better science, as I say, the IPCC made a very important, headline statement, right? It was one of the single most important statements of the big fifth assessment: near zero. Not net zero. Near zero for CO2, for methane and for —

Paul Jay: Where did this net zero terminology come from?

Peter Carter: Well, it came from the scientists. There’s been some net zero papers, a few of them, published a fairly long time ago. But after the big failure of the Copenhagen conference in 2009, and I don’t know whether it was coincidence, but the big disappointment came immediately after that conference. You know, the big disappointment. We all got very depressed about it because everybody knew in 2009 we’re in a catastrophic climate situation. Everybody knew that. The media were great. The media were telling us. And then, of course, you know, nothing happened.

But what did happen is that the science and the policy makers started publishing material that made solutions seem a lot easier. But a lot easier is not how you ensure our survival. So, they started talking about net zero. They changed the two degrees C limit from an equilibrium limit forever to a limit only by 2100. And of course, warming doesn’t stop. Climate disruption doesn’t stop at 2100. It continues for hundreds and hundreds of years.

So, “net zero” got into the policymaker lexicon. And also, they introduced as the key mode of calculating mitigation this thing called “cumulative carbon.” That had been published long ago, but they made it, again, very indefinite. We’ve got an indefinite cumulative carbon target. We’ve got an indefinite whatever-zero-emissions-means. My first website that I did long ago was on CO2 and explaining to people that CO2 lasts practically forever, as David Archer of Chicago, one of the world’s leading modelers on CO2 and climate, has said. It lasts forever. It doesn’t just last for hundreds and hundreds of years. CO2–our emissions in the atmosphere–lasts for many thousands of years. Therefore, it follows logically and by computer models that you have to stop emitting. You have to stop emitting CO2 because it is so persistent and long-lasting in the atmosphere. That makes it so cumulative: it builds up, builds up, builds up, builds up.

We now have a concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere that is the highest in 23 million years. I like to use this science because it’s such excellent science. These scientists can track carbon dioxide back this far: millions and millions and millions of years. I like to use that data because I think that’s something that would impress the public and impress policymakers. Isn’t this crazy?

Paul Jay: Let me just let me make sure I get clear on this. So, what they have in mind for net zero is that either through carbon capture or some new technology that will take carbon out of the atmosphere, you don’t have to phase out fossil fuels [as fast]. You can find other ways to get to zero.

Peter Carter: You got it, Paul. That’s the whole thing. It’s a deceptive, clever (in the worst sense of the word) way of not having to shut down the fossil fuel industry. Now, I want to point out that the IPCC 1.5 report was a great report. The IPCC did a tremendous job on that report. The best-case scenario, which happens to be called P1 and which is the only scenario which could possibly have a glimmer of a chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C and the only scenario that could limit to two degrees C, has emissions declining this year [2020] and then declining fast forever.

I was very impressed when I went to the COP 25 in Madrid, one of the big UN climate conferences, that the chair of the IPCC, Dr. Hoesung Lee, who is a traditional economist from South Korea, made a great opening statement to the conference in which he emphasized over and over that emissions had to go into decline this year. Yes, he said, this year. So, they have to go into decline, of course, on a constant basis. UNEP [UN Environment Programme] produced a report at the end of last year, which spelled this out very, very well. But all of the proper organizations are totally agreed, and all of the science is all agreed, that the main thing is to get emissions into a rapid, sustained decline this year. The rest of the stuff doesn’t matter.

Paul Jay: And it’s not happening. In fact, neither the Canadian government or the American government are even talking about doing this. When you look at the Biden climate plan, it actually doesn’t even talk about phasing out fossil fuel. He mentioned it at the end of a debate, but he says we have decades to do it. The Biden plan is mostly about carbon capture, which unless I’m wrong, carbon capture doesn’t work. I mean, it doesn’t exist yet. Am I wrong about that?

Peter Carter: Carbon capture has been in the IPCC assessment since the third assessment in 2001, for sure, that I recall. So, they’ve been talking about it over and over. Now they’re calling it “negative emissions,” OK? These are things which are just confusing and they allow the fossil fuel industry to continue to exist. And the one thing that is absolutely definite, and the IPCC is totally agreed on this as it’s said in its recent special reports: we have to end the fossil fuel industry. We have to replace it 100 percent, which we’ve known for years that we can do. The IPCC did a report in 2012 which stated that we could readily do it. We have to replace all fossil fuel energy. Of course!

Paul Jay: So, to not hit two degrees, how quickly does fossil fuel have to be phased out?

Peter Carter: The IPCC report has it being virtually phased out by 2050. This is not net zero. The best-case scenario, which is the only survivable scenario, is something like an 86 or 87 percent reduction of fossil fuel production [by 2050]. So, virtually nothing, OK? We know it has to be phased out by 2050 because we are so near to triggering a runaway. At 1.5 degrees C, most of the crops in the world are going to go into decline, and at two degrees C, practically all of them are going to go into decline. OK, so we have to get our emissions down as fast as possible. That’s the issue. The issue is not some vague net zero. The issue is, how fast can we get our CO2, in particular, emissions down?

Paul Jay: OK, let me ask something. Earlier you said how much agriculture is at risk. But if I understand it correctly, alongside phasing out fossil fuel quickly, we also have to change the way we do agriculture.

Peter Carter: Yeah, and one of the good things about the IPCC 1.5C assessment is that it said we had to make major changes at all levels of society. That includes agriculture. The two big sources of our emissions, of course, is fossil fuels–natural gas, methane, etc. But the other big source, which isn’t far behind fossil fuels is our food production. We’ve got big reports acknowledging this and telling us how much of a problem it is. So, we have to transform global energy production. That’s not hard. We’ve got these all of these amazing new technologies, of course, you know–they’re fabulous, they’re brilliant–for replacing all fossil fuel energy. We have to change that.

Paul Jay: You’re talking about wind, solar, primarily?

Peter Carter: Wind, solar, concentrated solar-thermal. We can’t give up nuclear. The IPCC acknowledges that nuclear is a very, very low carbon source of energy. So, we can’t give that up. I know people don’t like that. I’ve done a lot of research many years ago on nuclear energy. Yes, it does cause a small increase in cancer, but we have to survive now. We should be in survival mode. And our politicians are not.

Paul Jay: But let me take you up on nuclear for a minute. Even if one accepts that there may have to be some nuclear to deal with the crisis, is it even possible? It takes so long to get nuclear online and not just in terms of public opinion. Just in terms of investment and technology. The timeframe makes nuclear not a real option just because it’s going to take too long, even if you want to do it.

Peter Carter: The timeframes are a lot shorter than I or any of us ever realized or hoped for, I would say. We had two reports come out about six months ago. They came out about the same time, one from the United States and one from the UK. And they, particularly in the UK report, say we were really surprised. For the first time they looked into how fast we could actually replace all our fossil fuel energy with renewable energy, which was a very clever exercise. And you know what they said? A matter of years: 15, 20 years.

Paul Jay: Doesn’t that depend on how much money is invested in creating it?

Peter Carter: Oh, of course.

Paul Jay: I mean, if you had a massive investment in wind and solar, it wouldn’t take so long. If you leave it up to the marketplace, maybe it would but if governments intervened…?

Peter Carter: The governments are already intervening–in order to slow down the development of clean energy and in order to keep going with what’s killing the planet–literally, killing the planet–which is fossil fuel energy. They subsidize fossil fuels. They all do it. Actually, even the best of countries in every way sneak in some subsidies for fossil fuels. America, big subsidies; Canada, big subsidies; the biggest subsidies, of course, in China. By far, the biggest.

But MIT did us a great favor, first in a study in 2015 which they repeated about 18 months ago. They calculated all the fossil-fuel subsidies worldwide. This made it into the media because it turned out to be $5 trillion dollars a year. So, our governments are literally…they’re killing us.

Paul Jay: Well, if you were to flip that and have even more than that put into sustainable, renewable energy, it shouldn’t take 15 years to make a lot of solar windmills and retrofit buildings.

Peter Carter: Right, if you stop subsidizing. Civil society has really, really never been strong enough on stopping fossil fuel subsidies. There’s one good NGO called Oil Change International. They keep on it. But the other big NGOs do not. Spasmodically, they have a little campaign which says “stop fossil fuel subsidies,” and then it disappears. OK, the whole world should be breaking down government doors and telling their governments, “You have to stop subsidizing fossil fuels, which are killing us and destroying our future. And you have to do it now.”

Paul Jay: It’s the one thing about the Biden climate plan that seems actually really positive. He claims he’s going to phase out fossil fuel subsidies. It’s just not clear he’ll do it until all the other countries do it.

Peter Carter: He has stated, and I agree, that he is going to phase out fossil fuel subsidies. But I’ve learned over many years that when you’re assessing a leader’s policies on climate, you’d better go to the entire government. You better go to the people that he leads. So, this is the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, like the Republican Party, has its platform. And it’s very important to go through the platform. The platform of the Democratic Party does not have ending subsidies. They do not have ending fossil fuel energy. President-elect Biden doesn’t have ending fossil fuel energy.

I was very shocked when Vice President Harris had the debate with the Republican vice president.

Paul Jay:Pence.

Peter Carter: That’s right, Pence.

Paul Jay: You’re a Canadian. You don’t have to remember his name.

Peter Carter: She came out and said right off the cuff, very emphatically, Joe Biden is not going to stop fracking. Now, if you don’t stop fracking, you don’t stop destroying the planet. It’s really that simple. Fracking is not only a horrible method of extracting fossil fuels with all the water use, all the groundwater contamination. Fracking is what’s keeping the fossil fuel industry going. If it wasn’t for fracking, there’d be hardly any fossil fuel industry today. The industry would be all clean, renewable energy. The number one thing you have to do if you’re a political leader and you’re saying you’re going to do something about climate, to protect your citizens, to protect today’s children and all future generations–right at the top of your list, Day One: ban fracking.

Paul Jay: What about the Canadian situation? The Trudeau government talks about having real concern about the climate crisis. Of course, oil’s a big part of the Canadian economy. But this new legislation I mentioned where they’re going to have this accountability starting in 2030 and every five years from there. (I don’t know why they’re waiting until 2030.) I think they’re using this net zero terminology. So, what is it exactly they’re supposed to be measuring every five years?

Peter Carter: They’re using a goal that means nothing. If it means anything, the goal of net zero means we will still be burning more fossil fuels. So, right off the bat, that plan’s no use. It’s no help to our survival at all.

The other thing which is very important to do to analyze and really judge a leader’s policy is to go to the Energy Department. Go to the United States Energy Department’s Energy Information Administration, the EIA. They produce every year a really good, really thorough global review of energy future. It’s my favorite. It’s the most reliable one. Canada produces a document which they call Canada’s Energy Future. They’ve just produced their latest one for 2020. [It’s is produced by CER, Canada Energy Regulator.] What do these actual energy projections and plans being made by the people who drive policy say? They say by 2030, by 2050, we will be still burning a hell of a lot of fossil fuels. The American one says this. The last one was nearly a year ago. The recent one in Canada said the same thing. Sixty percent of Canada’s energy in the middle of the century is still going to be fossil fuels. That’s game over.

Paul Jay: Where are they at on carbon capture? Because they keep talking about it. Is there any reality to it? Will be effective even in a small way?

Peter Carter: No, it’s a fantasy. One, because you have to get your CO2 emissions down to virtual zero. Right? So, there’s no way that carbon capture and sequestration really enter the scientific equation. It’s a contradiction. It’s saying that the science says that we have to get down to virtual zero, but how are we going to do it is we are going to remove carbon from the atmosphere. It’s absolutely ridiculous. No, there is no capacity today at all to remove carbon from the atmosphere, let alone sequester it so it never leaks out.

Remember, we’re talking about planet Earth for thousands and thousands and thousands of years. That’s what we’re talking about. This is why policymakers in the past talked about all future generations in terms of climate change. Today, our leaders, our governments are actually condemning today’s children to inherit a hell on earth. You could just add up, which I’ve done recently for one of my presentations at the AGU [American Geophysical Union] conference, all the impacts that we know are going to happen at 1.5 degrees C and two degrees C. This is what you find: two degrees is really no future at all. Don’t even think about it. Don’t even go there. So, words defeat me: our so-called leaders saying that we have a plan to deal with climate change and that plan means we’re going to take carbon out of the atmosphere and eliminate it that way, and, they say, we’re still going to have fossil fuel emissions in 2050.

It’s impossible and it’s completely unnecessary because we know that we can do this. I think the public generally knows that we can replace all fossil fuel energy, all of it with a clean, non-polluting renewables, which means everlasting energy. I like to talk about what we are robbing from today’s children. My friend Reese Halter has published a great book called The Gen Z Emergency. We’re robbing our children of their future.

There are some children who know this. Greta Thunberg, for example. She knows this and she talks about it–in a very sarcastic, critical way; she’s the best at doing that, that’s for sure. She talks about how governments are relying on technologies that don’t exist and that probably never will exist. She’s absolutely right, Greta has sure done her research on climate change, I can tell you. [Laughs.] No capacity today. Governments and industry have been trying to develop carbon capture storage for decades. Governments have put big money, including in the United States, into trying to make carbon capture and storage happen. It’s not happened.

Now, the favorite of the policy makers is something called BECCS: bio-energy with carbon capture and storage. Until recently, it has been the favorite of the scientists, although they have changed, thank goodness. So, when governments are talking about negative emissions and net zero, they’re actually talking about what’s called BECCS. This is the fantasy; this is the delusion: burning massive amounts of biomass for energy, and then capturing and then storing all of the resulting CO2. Right? The ploy is that because the technology doesn’t exist, governments are trying to convince us to burn more

Paul Jay: Burn trees? Trees are part of the solution. You want to you want to grow a zillion more trees, not burn them.

Peter Carter: Of course, you do. Oh yeah, we should be planting trees as if there’s no tomorrow. Trees don’t do carbon capture. The CO2 will eventually go back. But if we do plant a trillion trees like people are talking about, we’ll modify for quite a long time the CO2 emissions and concentration.

You asked how bad things are. All the climate change indicators–global warming, ocean heating, ocean acidification, atmospheric methane, atmospheric CO2, you go on and on–they’re all at record levels and they’re all accelerating. They’re all accelerating. Atmospheric carbon dioxide, of course, is the most important one. It contributes the vast majority to global heating, but it also contributes all of the ocean acidification. If we don’t stop that, we’re done for.

Paul Jay: We only have a couple of minutes, but just explain that.

Peter Carter: A good research paper came out less than a year ago and they use models to project what will happen if we allow ocean acidification alone to carry on at the current rate —

Paul Jay: What is that? Ocean acidification?

Peter Carter: We get a mass extinction.

Paul Jay: What is ocean acidification?

Peter Carter: Ocean acidification is the direct impact of burning fossil fuels and putting CO2 in the atmosphere at an increasing rate. This increases in CO2 in the air. The surface of the ocean in contact with the air absorbs more CO2. The ocean is doing this all the time. But now it’s absorbing more and more and more CO2 and that acidifies the oceans. It changes the pH, in the terms of the scientists. But they all call it ocean acidification because at least that’s a term that the public understands.

Ocean acidification, of course, is obviously extremely damaging to marine life, marine ecosystems. There are ocean acidification hotspots all over the world. And unfortunately, one of them is near where I live. So, ocean acidification alone, which is the direct impact of burning fossil fuels which puts more CO2 in the atmosphere, destroys the planet. It destroys the living planet. It destroys our future.

We really are so fortunate. Paul, you and I came into the world when the world was literally at its best for millions and millions of years. We came into the world where there had never been more biodiversity on the planet. There never had been a greater wealth of life and wonderful species on the planet. Right? But now, because of the industries, the big powerful corporations, and our compliant, terrible political leaders which are maintaining the fossil fuel industry… Look, human beings progress, right? Civilization progresses. And obviously, our destiny, which we’re looking at is not to have any pollution from our energy production and to have unlimited energy production. Totally safe. And the more we produce renewable energy, the more we have, the better it becomes, and the cheaper it becomes. So, it’s a no brainer. It’s an absolute, total no-brainer.

Paul Jay: We’re not living in a rational system. No-brainers are part of rationality, and this system ain’t rational. I gotta wind it up. But we’ll do this again, Peter.

Peter Carter: OK. OK, thanks, Paul. It’s been good talking to you.