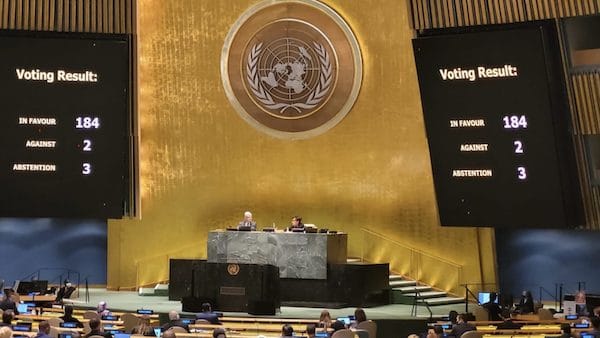

Cuba won another diplomatic victory in the General Assembly of the United Nations this Wednesday against the government of the United States. The majority of countries (184) voted in favor of the resolution which calls for the lifting of the blockade against Cuba. The resolution has been brought to the UN every year since 1992, except in 2020 when the government of Havana was unable to present it due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This victory is a reminder of the Cuban people’s long wait for an act of justice that can rectify the worrying situation, which is a mix of the abuse of authority, the disproportionate use of violence, and the very specific intention to “destroy, totally or in part, a national, ethnic or racial group, in its totality,” the UN’s definition of genocide in its 1948 Convention.

Only very few cases of mass killings have been considered genocides unequivocally by the international community. However, there is no other name for this horror which has lasted for more than 60 years and has forced several generations of Cubans to go about their daily lives under a heavy fog. This powerful elite carries out inhuman monstrosities against millions of people for the mere crime of existing. Is it not genocide to deny people, in the middle of a pandemic, medicine and food, access to internet services to the majority of people, to finance and trade between equals? If so, we must then, like Raphael Lemkin, invent a word for this nameless crime.

It is difficult to account for how many in Cuba have died because they did not have the medicine they needed or because it did not arrive on time. The report presented by the Cuba’s Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez, on the damages of the blockade in 2020, has 60 pages without one adjective. The report is merely a list of what happened, excessive costs, items that did not arrive on time because they had some component from the U.S. –from a plane to a respirator that was destined for an intensive care unit-, names of companies that have refused to supply the island with the technology, raw materials, reactive agents, diagnostic kits, medicine, devices, equipment and replacement parts needed by a public health system.

A friend told me that the images of George Floyd’s assassination had a strong impact in Cuba. Being suffocated on the ground by the police officer who refused to lift his knee off his neck, despite the cries of the victim saying that he couldn’t breathe. The video went viral across the world and was the catalyst for the largest anti-racist protest in the United States since the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

We understand the feeling of impotence of the people of the United States who feel rightly so that this is a systematic abuse of power. In the case of the 8 minutes and 46 seconds of George’s agony, it was key that the entire incident was recorded. The question that remains, after the conviction of the killer cop, is how many other people have been killed or have suffered in silence simply because there was no camera when the system didn’t let them breathe. We know that there is always a knee on someone’s neck, suffocating them. This is what happens with the blockade. This strange word that may seem to be abstract for many, but not for the person who finds themselves in the emergency room in Cuba, has a sick child or has spent six hours in line to buy food that before the 242 additional sanctions added by Donald Trump and before the damn pandemic, could be found with less difficulty.

Joe Biden’s representative at the UN reached new levels of cynicism when they said that the blockade is the responsibility of the Cuban government which uses it as a pretext to remain in power. This is like George Floyd’s killer saying his knee on somebody else’s neck was the victim’s excuse for suffocating.

As such, these are moments of joy in Cuba as we learn that once again that from the New York headquarters of the UN, the world said no to the U.S. blockade. This coincided with more hopeful news: Cuban scientists were able to finalize the first two Latin American vaccines. One of them, Abdala, has a 92.28% rate of efficacy.

This article was first published in La Jornada.