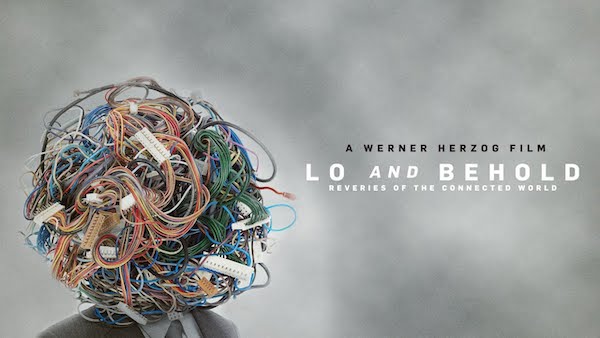

Director Werner Herzog’s documentary Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World (2016) begins with “Internet pioneer” Leonard Kleinrock, who welcomes us into the, yes, actual laboratory where it was “born”! To Wagnerian strains in the soundtrack, Kleinrock complacently calls the place “a holy shrine”–quite a revealing phrase for this acolyte of possibly the last of the false religions. We then hear another “pioneer,” Bob Kahn, who matter-of-factly notes his early involvement in the Pentagon development of Arpanet (DARPA).

Is Herzog’s primary intention satirical? I fear not. As in his other recent documentaries, he seems to wander about, credulously interviewing often eccentric persons–in this case, cyber-tech promoters with obvious vested interests. Herzog’s wandering–I wouldn’t call it a coherent narrative–jumps from one thing to another without any logical continuity, and he passively allows cybertech developers free air time to pronounce, with breathtaking hubris, their enthusiasm for the forthcoming “transhuman” future–the term here referring, not to gender-neutrality (sex presumably redundant), but to the “empowering” extension into (and fusion with) “artificial intelligence.” Despite his prolific churning-out of one documentary after another (after all, they’re cheap to make!), Herzog is not a good documentary filmmaker–and still less, an investigative journalist. (Compare his docs with the best ones made by Alex Gibney or Errol Morris.)

With an almost adolescent naivete, Herzog generally accepts the hype, almost reading verbatim from Silicon press releases. For instance, robotics: teams of robots, he rhapsodizes, will soon be sent on rescue missions to “disaster sites.” (What disasters? Caused by what? Why not prevent them in the first place–but then again, no revenues generated by unemployed robot-teams!). One may add that, with robot-forces, highly lucrative wars can continue (robots in “boots” or as drones)–with no battlefield “casualties” (for our “side”).

We are shown a short promotional video: a small robot pours itself a glass of water, and is then given an “affectionate” hand-squeeze by an admiring woman. This last gesture speaks volumes: the age-old fallacy of animism—fallaciously endowing inorganic forms with sentient “responsiveness.” In short, people, deprived of needed emotional sustenance in their human contacts, are turning–in self-deluding desperation–to the “companionship” of robots. (To be sure, most lonely people today are still sane enough to prefer a mammal–generally dog or cat–as a “beloved companion.”)

But why, in the first place, this mono-maniacal fixation on an artificial substitute for “the human”? One technocrat in the film smugly dismisses human beings as obsolescent: “robots learn faster.” Learn what? And for what purpose? All the “technotopians” interviewed seem to envision sedentism as an inevitable outcome: motionless, confined persons commanding their computers and robots to do things and get things for them. But, as their musculature atrophies and their senses become conditioned and standardized, cyber-”empowered” persons may struggle with an ultimate conundrum: a compelling reason to stay alive. It is a sorry state of affairs when the aforementioned Kleinrock can assure us that such total embedding in an entirely “inter-active” system can be done in “a very humanistic way”(!). (At the same time, with maddening contradiction, Kleinrock is adamant about how the Internet has destroyed the capacity for critical thinking in the young people who’ve grown up with it!). Of course, Kleinrock and the others ignore the ultimate (unasked) questions: What for? To what end?

In an awkward moment, a tense Elon Musk admits that he has dreams–but that he “only remembers the nightmares.” Are such fears–and he has warned us, among other things, of the looming danger of “killer robots”–rooted in the proverbial unpredictability of human behavior? Perhaps control can be secured–if “Artificial Intelligence” maintains an entirely calculated, measured and predicted social order? Or, perhaps such unresolved anxieties can only be assuaged through an ultimate escape–say, to the planet Mars?

Indeed, a competent interviewer might have asked these self-satisfied technophiliacs if they ever enjoyed full emotional intimacy in warmly affectionate, sexual surrender? (See: Wilhelm Reich on “character armor” and its mechanistic, sadistic impulses.) Did they ever stand naked (figuratively speaking)–dropping all poses and neurotic defenses–and share their real deepest emotions with another in all sincerity? In short, one can’t help suspecting that the driving obsession with lifeless machines–engineered to have “human-like” attributes–not only guarantees control but also compensates for their arrested emotional capacities.

After all, walking and carrying, caressing and copulating, touching and laughing, “bringing up” (nurturing) children, admiring and co-inhabiting the earthly landscape with fellow creatures, cultivating an ever-enriched capacity for aesthetic feeling and sympathetic understanding–all these and more enhance biophilia. And thus: a fierce zest in being alive!