China owns almost half of the world’s coal power generation capacity. But as the country prepares to peak its domestic carbon emissions by 2030 and reach carbon neutrality by 2060, its continued involvement in developing coal power overseas has drawn increasing attention from global stakeholders.

Earlier this year, China pledged to strictly control coal power generation at home and recommitted to raising the environmental standards of projects being built as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. In April, China and the U.S. also committed to helping maximise international investment and finance for developing countries to transition to low-carbon energy.

The latest G20 ministerial meeting on environment, climate and energy further elevated the urgency of the issue ahead of UN climate talks in Glasgow later this year.

A new policy brief written by myself and Kevin P. Gallagher at the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, sheds light on China’s substantial overseas energy footprint. The research, which draws on data from the China’s Global Power Database (CGP) and the Global Coal Public Finance Tracker (GCPFT), has found that Chinese financing was involved in 13% of the coal power capacity operational or under development between 2013 and mid-2019. In other words, 87% of total public and private finance for overseas coal plants was provided by entities outside China.

Promisingly, China has increased financing for renewables over the past five years, but this has not been enough to slow the acceleration in global temperature rise–so far.

How much does China invest in overseas coal power?

A number of attempts have been made to estimate the scale of China’s overseas coal involvement, but none has been comprehensive. The latest Boston University research merged relevant sections of the CGP and GCPFT to provide: an estimate of the total installed capacity of coal power generation outside China between 2013 and mid-2019 with the participation of Chinese finance and investment; and the share of that China-funded capacity in all the newly added coal power generation capacity outside China. The actual total Chinese investment is likely even lower since the research counted the full capacity of a coal power plant as long as a Chinese entity provided loans or investment, regardless of the entity’s share in the project, which is below 100% in most cases.

Funding for a project could come in the form of foreign direct investment, portfolio investment by corporate and fund investors, or debt finance by commercial or policy banks (public finance). Foreign direct investment and policy bank finance constitute the majority of Chinese overseas investment and finance in the power sector.

During the period covered by the study, Chinese investment and finance participated in 68.8GW of coal power generation capacity already in operation, under construction or being planned outside China, equivalent to 13% of all such capacity during this period.

Some of the largest coal power projects that had been at the planning stage have of late been shelved or deferred, such as the Rahim Yar Khan (1.3 GW) power plant in Pakistan and Egypt’s Hamarawein 6.6GW power plant. Covid will likely continue to disrupt some of the planned projects.

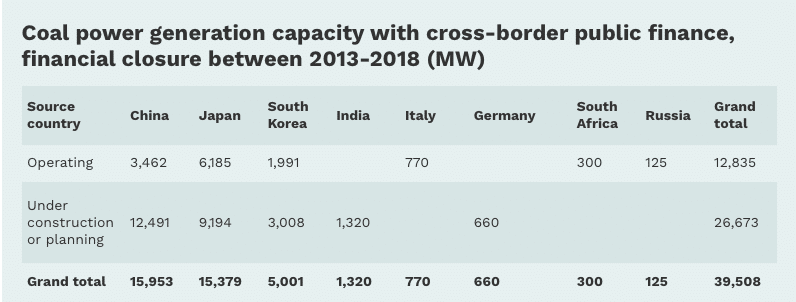

The study found that China is the largest public financier of overseas coal plants, through its two policy banks, the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. The country accounted for 40% of all coal-fired power generation capacity supported by public finance that reached financial closure between 2013 and 2018, closely followed by Japan (39%) and then South Korea (12.7%).

In comparison, overseas coal power generation capacity supported by Chinese state-owned and private commercial entities (excluding those with Chinese public finance calculated above), is half as much as that supported by public finance. Most of these projects are still under construction or at the planning stage.

The data shows that China’s financial involvement in overseas coal power development is still substantial, especially in terms of public finance commitments, though not as dominant as some commentators have suggested. Considering the world’s urgent need for climate change mitigation, the next question is whether Chinese financing can be harnessed for a global transition toward low-carbon development.

How fast is China moving away from coal power overseas?

Chinese overseas energy financing has clearly shifted in the past decade.

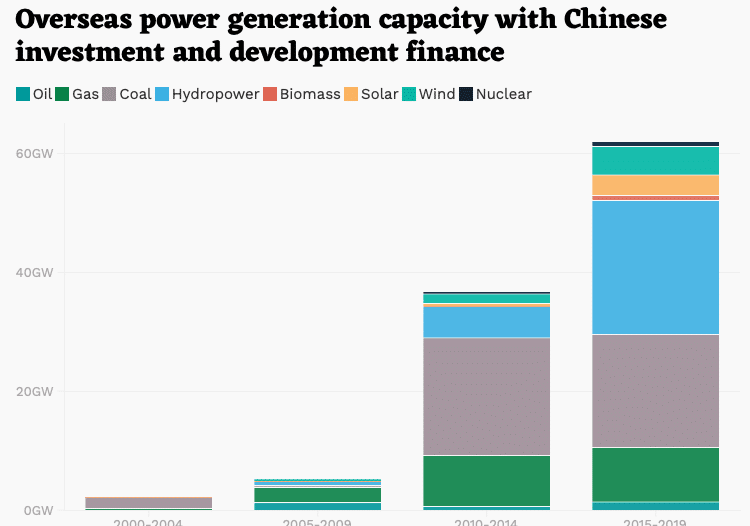

Between 2000 and 2019, Chinese foreign direct investment and development finance funded 106.2GW of overseas power generation capacity in operation; of that, 38.5% was coal-fired and 38.8% was non-fossil energy, including hydro, solar, wind, geothermal, nuclear and biomass. As shown in the graph below, Chinese foreign direct investment and development finance in power generation started to rise substantially in 2010 after the global financial crisis. Fossil fuel power generation dominated between 2010 and 2014, and remained at a high level in the following five years.

Financing for renewable power generation started to pick up in the most recent five-year period, rising more than fourfold between 2015 and mid-2019 to account for 51% of the overseas power generation capacity that Chinese investment and finance was involved in (see the graph above).

By 2019, hydropower accounted for 70% of the overseas non-fossil power generation capacity funded by China. However, the climate and environmental impact of these projects needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis–some hydropower projects that flood natural carbon sinks may cause greater carbon emissions than fossil fuel power plants of the same capacity.

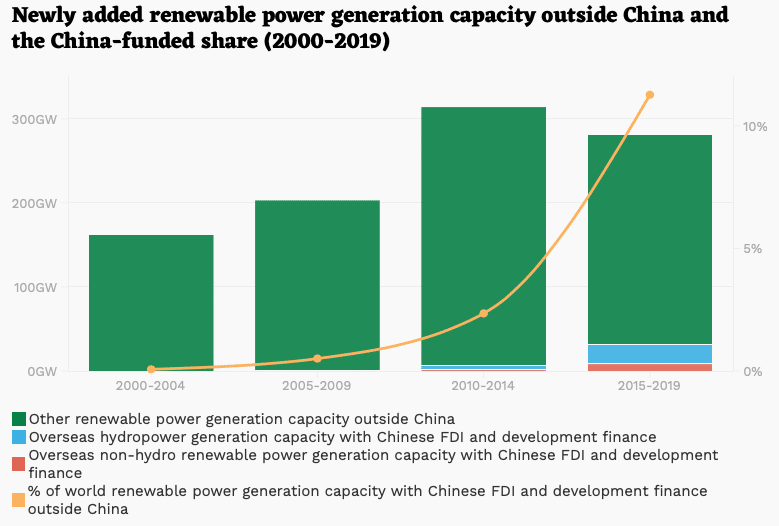

China-funded non-hydro renewable power capacity is also rising steadily but accounts for just 4% of the world’s non-hydro renewable energy growth outside China between 2015-2019.

S&P Global Platts (2019), World Electric Power Plants Database, Boston University Global Development Policy Center (2020), China’s Global Power Database

In contrast, despite the growth in China’s overseas renewable energy investment in recent years, the share of Chinese-financed coal power capacity in the rest of the world’s total newly added coal power capacity climbed to a new height of 16% between 2015 and 2019, according to the data.

How close is this to the Paris Agreement?

Chinese investment and finance have been crucial for meeting the fast-growing energy needs of lower-middle-income and low-income countries. Such nations receive only a fraction of the world’s energy investment, despite accounting for 40% of its population. Between 2000 and 2018, 43% of Chinese power generation investment overseas went to these countries. However, for the world to achieve the Paris Agreement targets, more of these investments need to be diverted to renewable energy.

Currently, overseas fossil fuel power plants with Chinese financial involvement are generating approximately 314 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2emissions per year, or about 3.5% of the annual CO2 emissions from the entire global power sector outside of China. In 2030, coal power generation with such financing will be pumping a total of 525 Mt of CO2emissions per year into the atmosphere, assuming all projects under construction or in planning come online and no operational plants are retired. That is nearly 10% of the annual emissions that the Paris Agreement requires the world to reduce by 2030, compared with the 2018 level.

At this point, any new investment in coal power could undermine the global endeavour to limit warming to well below 2C, and risks becoming stranded assets as host countries step up their climate actions.

A promising trend

We are now seeing a promising trend. Since 2017, the two Chinese policy banks that have been the main contributors to overseas coal power generation capacity have been decreasing their overseas coal finance, and increasing lending in power transmission and distribution, a sector crucial for scaling up renewable energy. However, unlike many of the Western-led development finance institutions that have set up internal climate policies and restrictions on fossil fuel financing, Chinese policy banks have not yet established such regulation on bank level, and do not yet limit fossil fuel finance overseas.

While global energy demand fell in 2020 due to the pandemic, global investment in energy transition actually increased. The power sector could be a significant driving force in powering the world’s path to a sustainable recovery from COVID-19.

In today’s economic circumstances, for Chinese banks and power sector investors, cooperation with multilateral and host country development finance institutions might offer better policy coordination and risk management for renewable energy projects. Such cooperation frameworks could help to further scale up investment in the power sector across the world. China could also leverage platforms such as the G20, of which China is a member, to engage in collective actions, to advance its climate efforts in terms of international climate finance expansion, information disclosure and policy coordination.

Chinese banks could introduce climate targets, emission standards, or internal carbon prices, and eventually match the environmental standards of global best practices to phase out financing for coal power projects. Cleaner energy infrastructure systems also call for greater investment in electricity grid connectivity, smarter power system operation, and infrastructure for distributed energy resources. Policies supporting innovation and investment in these sectors, as well as healthy transformation of the domestic energy sector, would also be crucial for the future of sustainable development.

As the data shows, China has a key role to play in the global energy transition. By combining rapid phase-out of coal finance across the world and facilitating the world’s energy and economic transition, China has the opportunity to assume international climate leadership during an absolutely critical time.

Ma Xinyue is the research coordinator for the Global Development Policy Center’s Global China Program.