The Trial

On August 25, 2020, Kyle Rittenhouse killed Joseph Rosenbaum and Anthony Huber, and wounded Gaige Grosskreutz. He is not the subject of this essay, and if we could, we would avoid mention of his name. The center of this story is all those who took part in the George Floyd Rebellion, an uprising composed of thousands of demonstrations and hundreds of riots across the U.S. It was this composition that lit the sky on fire during those wild nights in Kenosha last year, and it is from within the force of this event that we speak.

Kenosha is a boiling point in this story. Three nights of riots in this Wisconsin town were the gift the rebellion shared with a racist order that put seven police bullets in Jacob Blake on August 23. If Rittenhouse figures into this history, it is only as a symptom: the child of a declining order who has inherited the anxiety of the property relation. How fitting that a scared teenager, clinging to the thin blue line delusion, does the work of order for a society stuck in perpetual infantilism.

The Rittenhouse verdict is expected any time now, but the real trial of our epoch is only just beginning: will the forces forged in the fires last summer remain true to the spirit of the George Floyd Rebellion? Will they catch sight of the storms approaching on the horizon in time to act accordingly? In what follows, we seek to do both: to gaze back into the event, to remember what was powerful in it, and thereby to snatch its memory from the jaws of the law; but also to read from it signs of a future still to come.

Our guess is that, as we look back on these events, future generations will see in them not a “last gasp” but a leap, a transitional moment in the regime of power that grips this country. The truth of the event is the truth of a world wielding violence as a means of shedding its skin. What the battles to come must draw from the uprising is less its form than its spirit. Above all, they must avoid the traps that it laid out for all of us.

The Fight and the Hold

The spirit of the George Floyd Rebellion animated the Kenosha riots from their first moments. The viral videos of the brick sending the responding officer to the ground, or the Molotov thrown from the crowd that assembled spontaneously at the scene of Jacob Blake’s shooting, tapped into a mounting fearlessness on the part of the people that had been growing nationwide. The determination that first night was electric. It felt like unfinished business from seven years ago, back when #Ferguson dominated our feeds. Every measure the police took to quell the rage was turned back against it. One by one, the garbage trucks by which the city sought to block off access to the courthouse were transformed into burning barricades by the unruly crowd. The infrastructure designed to pacify the crowd was converted into a source of its own power–a reversal of police counter-logistics. Pitched battles and roaming destruction continued until dawn.

We can still hear the echo of rocks and bottles clanging against the armor of police bearcats from the second night. A crowd of a thousand outside the courthouse was attempting to disperse the police line, trading flashbangs for fireworks, when a certain exuberance and ferocity washed over us.

These days, whenever uprisings anywhere hit upon tactical innovations the lesson is taken up in real time everywhere. Consequently, the black bloc techniques that spread like a meme twenty years ago are now diffused through the entire demonstration. Like the black teenagers from Chicago who donned Guy Fawkes masks in Ferguson after bearing witness to Occupy, the umbrellas, shields, and helmets of Hong Kong now appear in every corner of the demonstration.

These days, whenever uprisings anywhere hit upon tactical innovations the lesson is taken up in real time everywhere. Consequently, the black bloc techniques that spread like a meme twenty years ago are now diffused through the entire demonstration. Like the black teenagers from Chicago who donned Guy Fawkes masks in Ferguson after bearing witness to Occupy, the umbrellas, shields, and helmets of Hong Kong now appear in every corner of the demonstration.

In some larger cities last summer, it felt like the terms and conditions of protest were decided in advance. But during the first three nights in Kenosha, there were no black leaders or activists trained in allyship to authorize why or how anyone took part. There was no activist leadership to mobilize, and no one made it their business to suppress the rage of others: no kneeling, no good cops, no bad protesters. Everyone was welcome to fight, in whatever way they felt comfortable.

There’s something unique and complete about these moments, an interlude that suspends our individualistic self-doubt and paranoia. The more they test their courage, the more people begin to rethink their environment, creating makeshift weapons and ad hoc defense structures. But beneath the technical necessity of grabbing tools on the go and gut checks, there’s another truth that’s important to insist upon: a shared experience can very quickly forge the potential to put life in common. The way you move through a crowd in this situation feels as impossible during moments without unrest as it does normal and even serene within them. It is in these “real states of emergency,” as the old social contract collapses, as disaster exposes the incompetence of government, and as an uprising imposes its new polarity that we begin to identify our own needs and safety with those around us. People form bonds effortlessly, and on the basis of real contact. There’s a certain ease with which we fall into the care of an improvised and dangerous community.

In much the same way, events like Kenosha complicate racialized assumptions. It’s not just the law that appears to evaporate–within the riot, the racial codes of our society begin to malfunction. If the impact of urban planning after the sixties was to instrumentalize architecture and infrastructure as a means to concretize and materially confirm the color line, then by attacking urban planning and the police who enforce this segregation of the landscape, these exceptional events can open up a space of communion across racial lines. In the heat of the fires in Kenosha, locality and ethics superseded race as the basis of any immediate encounter. On the one hand, you were more likely to be confronted with suspicion if you weren’t from the neighborhood; yet you were just as likely to be welcomed with open arms if you appeared to fit someone’s imagination of “Antifa.” The same person who gave you the side-eye earlier will stand with you once you make it clear you’ve got skin in the game.

These moments are transformative in a real sense. Whites born into a life distant from violence, who may be ashamed of their lack of connection to black and latino experience, or who have been taught to please the police and fear blackness, encounter black desire on the shared terrain of resisting captivity. Likewise, black people who have only known whites as racist, or who might know a handful of “down” but still kind of goofy whites are now thrust into uncharted territory. To come upon whites with a disposition to fight at the same time as they are confronted by other people of color acting like clowns and attempting to quell the crowd’s anger–such encounters can break down overly simplistic ideas of fixed identities, whether the corny white figure depicted in black comedies or the revolutionary subject of the black radical tradition. The result is a contradictory cocktail of “pessimism and optimism, specifism and universalism” wholly contingent on a delicate mixture of anti-social and social violence, which has the power to momentarily shake us awake from the racial nightmare.

The hold’s terrible gift was to gather dispossessed feelings in common…

In the streets that second night, people were looking out for one another, reminding each other to wear a mask, shouting “cover your face!” when glass was breaking, and checking that cameras were off. With no one giving orders or telling people how to feel, what to do, or where to go, the needs of the collective body were easy to spot and anticipate. Complete strangers intuitively offered and asked for help. How fluidly this shift happens shows how easy it is for people to act in concert once an unspoken pact about the type of freedom we are participating in has been made. At one point, a car caravan was giving cover to the crowd in the street so that bearcats couldn’t enter the block. What people decided to do within that sudden moment of freedom is not what matters. If property is destroyed, it simply reflects back on what causes people to create these spaces of freedom to begin with. Such acts are always infinitely more gentle than what they serve as a response to.

By contrast, where megaphones compete with each other to give the same speech, or activists attempt to nag a crowd into submission, a kind of ethical sectarianism emerges and fractures the improvised community. Those whose penchants align move in sync, but the fabric of common experience is now riven by mistrust. The same is true when police run impact-round drive-bys in their bearcats, or a collection of armed non-state actors fill the sea for a teenage cop lover to swim in: the fugitive community splinters, and the situation recalibrates with sharper and more hostile edges.

On that second night, the bonds born in rebellion still held strong. As the crowd reached the Department of Corrections building, fire from the furniture store began to illuminate the distance. The lack of appointed leaders gave way to generous excess. Firework mortars lit up the darkness, and the facade was covered in slogans: “Can you hear us now?”, “Prison demolitionism now,” “Rusten Sheskey you did this.” The car caravan arrived, jubilantly playing music, yelling and laughing, riders hanging out windows. Someone dared the crowd to “burn that shit down!,” an appeal met with cheers. The front door’s glass got smashed, kicked out, and masked figures entered the building. The side doors were pried open and others followed suit. The DOC would burn long into the night–a microcosm of this particular hell on earth, now consummated in revelatory inferno. As the crowd pushed off, a reveller exclaimed:

I’m never going to see my PO ever again!

American Hell

The exurbs of the Midwest are a particular circle of hell in which the nightmares of the twentieth century torment the living. Twin failed promises of white flight and black middle class dreams now fuse into one of the most segregated terrains in the US. Scantily lit neighborhoods, visible poverty, and a pervasive feeling of no way out form the cultural tapestry of towns like Kenosha.

How quickly this terrain descended into a warzone. The bloodshed itself was nothing new: there had been shots fired since the uprising began, with over twenty killed between May and November. Let’s recall that it was only five years ago that black Iraq vets in Dallas and Baton Rouge put their fingers on hair triggers. It was only two years prior to that when Chris Dorner single-handedly caused a county-wide crisis by waging unconventional and asymmetrical war against the LAPD over its internal corruption and racism. There are hundreds of millions of guns in America, and a population hardened by a history of defeat, forever wars, and public massacres. We struggle to make sense of Kenosha because the truth of it is more terrifying than the conspiracy theories.

The origins of Kenosha set the tone for its sordid history. In the 1830s, the Potawatomi who had originally been hostile to U.S. forts were growing more desperate. Seeing the writing on the wall, their leaders hoped that aligning themselves with the U.S. in the Blackhawk War would garner favor, allowing them to keep their land as the colonial project marched west. Instead, the poverty inflicted from the war forced them to sell off their remaining land in Wisconsin, and they found themselves relocated to reservations in Iowa and Nebraska. Their experience was in no way an anomaly, but only the tragic repetition of the originary operation of the law, now seen from the perspective of the vanquished.

The American working class would soon follow suit. Following post-war union compromises, Kenosha was one of many in a constellation of industrial cities selling the American dream to workers. Like the suburbs and exurbs of Detroit, this exchange was made on the basis of rejecting class solidarities and, in particular, of suppressing any link between the class struggle and the civil rights movement. This fissure was only further exacerbated throughout the tumultuous sixties and seventies. The reactionary posture of the AFL summarizes the weakness of Democratic strategy over the last half-century: the retreat from class struggle cost everything it sought to protect. Nowhere is this catastrophic bargain more obvious than in Kenosha. Powerless to stop the wave of automation, Kenosha’s auto assembly factory went from 16,000 workers in the sixties to 6000 in 1988, when  finally closed the shop. A mere 800 workers could do little more than rally and wave signs from their desert of highways and stripmalls in 2009, while Chysler CEOs pocketed their government bailout and ended all operations.

finally closed the shop. A mere 800 workers could do little more than rally and wave signs from their desert of highways and stripmalls in 2009, while Chysler CEOs pocketed their government bailout and ended all operations.

It’s no coincidence that the George Floyd Rebellion was initiated in the Midwest, before spreading to the coastal cities. The rebellion had its roots among the grandchildren of the defeated workers movement. It was a long overdue encounter between people who have been struggling for ages, militant activists inspired by images of nationwide rebellion who knew they had much to learn, gangs operating on informal truces, and young wild ones who dwell in a time without future.

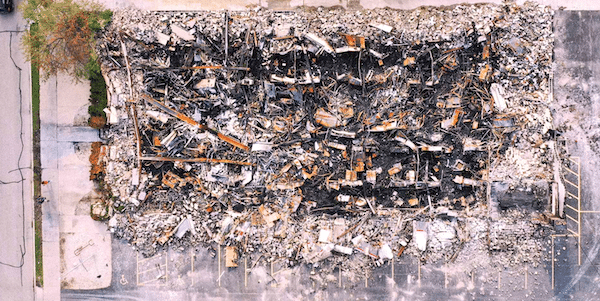

Over forty structure fires rained ash over Kenosha. The inferno swallowed car lots, banks, check-cashing places, beauty salons, dollar stores, the DOC, and little nothing shops. The destruction was gratuitous, yet it seems mild in comparison to losing the ability to walk and the permanent removal of bodily organs, which is what the cops left Jacob Blake with.

The sympathy echoed by some business owners who lost their shops to the fires–“Burn it twenty times if it gets justice!” one cried–reveals the hell that is hiding in plain sight. Why haven’t cops been able to stop it, why can’t the firefighters put it all out? In the end, the riots only expose that which most people hope they can avert their gaze from. The wealth that fled Kenosha pronounced its death sentence long ago.

Fraternal Violence

Neoliberal policy hollowed out Kenosha, promising a tiny subset of workers access to the American dream while cannibalizing the rest. This truth was lost on the armed citizens who arrived on the eve of August 25. The spectral figures that once hovered at the edges of American protests have now stepped forward and announced themselves as an armed reactionary force. In the years leading up to the 2016 election, the far-right saw a powerful resurgence. Trump tapped into a diffuse feeling of being orphaned by modernity, left behind and angry, and succeeded in reframing it along ethnic and racial lines. The constitutionalist right began to show increasing sympathy for the fascists on the wedge of free speech issues. While the latter took to street brawls, the threeper militias mostly stuck to the sidelines. Now, because the rebellion had called into question the sanctity of white propertarian law, they have entered the fray. The Facebook call for armed citizens “to protect lives and property” in Kenosha was an invitation to localist anxieties, militia LARPers, and every QAnon freak within one hundred miles. Reactionary political formations and their expressions of force aren’t only the result of “white fragility.” They are also the consequence of those same compromises made by labor decades ago.

There is a terrifying anger that we all possess, a capacity for violence that’s funnelled through both “legitimate” channels like the cops and military and illicit channels like gangs and militias. It’s no coincidence that the other side of that capacity for force is the fraternal principle on which all of these organizations are founded. The desire for a sense of belonging and community are, at the core, the real driver of this violence: people will kill to belong. Given this, it should surprise no one that Kyle Rittenhouse–a would-be school-shooter steeped in an escalating cultural war–elevated his love of police to the murder of demonstrators.

Kyle Rittenhouse represents the funneling of suburban despair through the vile fiction of cultural war. While the Democrats are only too happy to continue their expulsion of the working class and tie their ponies to Silicon Valley’s race to leave the planet, the Republicans have aligned themselves with the oil and extraction industry and want only to make a buck while the world burns. Exaggerating cultural differences as political–or even ethnic — is advantageous for the elites, because if America were to come to grips with the ruin they have wrought, those hundreds of millions of guns might find new targets. They would prefer we commit fratricide because a left-right civil war is far easier to manage than the possibility that we might leave their terminal civilization, and take our labor with us.

Kyle Rittenhouse represents the funneling of suburban despair through the vile fiction of cultural war. While the Democrats are only too happy to continue their expulsion of the working class and tie their ponies to Silicon Valley’s race to leave the planet, the Republicans have aligned themselves with the oil and extraction industry and want only to make a buck while the world burns. Exaggerating cultural differences as political–or even ethnic — is advantageous for the elites, because if America were to come to grips with the ruin they have wrought, those hundreds of millions of guns might find new targets. They would prefer we commit fratricide because a left-right civil war is far easier to manage than the possibility that we might leave their terminal civilization, and take our labor with us.

The culture war is an attempt to reframe epochal tremors through two visions of American history. According to one of these visions, America is the leader of freedom and democracy whose institutions have been momentarily undermined by bad apples and a cruel multiculturalism, holding the country to account for its past and thrusting the nation into a future without tradition. In the other vision, America is the melting pot of rich traditions which shape its culture through their mixture and in which historical oppression can be resolved through a happy integration into its institutions and the market. Each of these narratives miss what is potent about America. Conservatives cannot see that a robust practice of freedom is nourished by each of us increasing our attachments, weaving ourselves deeper into worlds, and that only through those bonds do we create traditions worth fighting for. Liberals fail to see that it is precisely the pulverization of cultures by the market that creates the contradictions they attempt to solve with cynical representation. There is no American culture, only a vast continent on which a multitude of forms of life take shape.

Governing Hostilities

Rittenhouse foreshadows a future of armed conflict and false narratives, of child soldiers and fatal mistakes. Bloodletting in the hinterland against a backdrop of silicon megacities at the coasts. This horizon promises only catastrophe, which is hiding in the language of law. What’s at stake is neither ‘self-defense’ or ‘murder.’ The true meaning of the Rittenhouse trial lies in the way it frames and redraws identities for future conflicts to come. Citizen or terrorist–it’s a distinction to which every half-thought Tweet contributes.

The trial exceeds the courtroom. To break the functioning of the law, it’s not enough to rebel against the violent excess of the state. At a deeper level, it means refusing to play the game of good and bad identities that governance imposes–refusing to fall in love with your reflection. It is no mistake that the law will unevenly distribute justice in the service of the reigning order. We must learn to see the trial and the spectacular machinations of law more broadly as political techniques that weave and mend the social fabric, while operating directly upon our collective imagination of hostility.

Bruce Schroeder, the judge presiding over the Rittenhouse case, recently exclaimed that “This is not a political trial.” If the political is the event of confrontation between two fighting collectivites–through which friend and enemy are revealed and in which lethal force can never be discounted–then nothing is more political than how the law shapes and defines those collectivities as such, and how it orients them to act politically. This trial is an instrument for shaping collective identities in the culture war farce, and fuel for its fire.

The outcome of this case is likely to be more armed conflicts. The legal precedents set and the unevenness of punishment will make demonstrations increasingly more armed, with participants more prepared to defend themselves against lethal force. Likewise it will set a precedent in the frame of armed conflict for how to be perceived as a citizen rather than a terrorist–because governments know they need both. Visions of social revolution are being replaced by images of the Purge.

The outcome of this case is likely to be more armed conflicts. The legal precedents set and the unevenness of punishment will make demonstrations increasingly more armed, with participants more prepared to defend themselves against lethal force. Likewise it will set a precedent in the frame of armed conflict for how to be perceived as a citizen rather than a terrorist–because governments know they need both. Visions of social revolution are being replaced by images of the Purge.

Such paranoid narratives are expressions of a world in which consensus reality has collapsed. We are losing not only the epistemological foundations to ground our perceptions, but the very ability to ask ourselves nuanced and difficult questions. Kyle Rittenhouse’s lawyers claim he acted in self-defense. His supporters believe a narrative in which he came to Kenosha as a civic-minded do-gooder, who was then attacked and had to shoot. Pundits on the right believe he was nothing less than a hero who gave Antifa what they had coming. The prosecution claims he acted recklessly and committed homicide. Liberals and portions of the left believe Rittenhouse is a white supremacist who came to Kenosha to act on his fascist beliefs. But on the night of August 25, nothing felt so clear. There were signs of each of these narratives–dog whistles, if you had the ear for them–but truth was obscured by a dark cloud of assumptions and tensions. If you were there, the polarity against the police was suddenly rerouted and the face of the adversary contorted. You had to gaze into a fog of flashing lights, rage, and gunmen to attempt to perceive reality.

Rittenhouse is the logical fusion of the liberal and conservative narratives surrounding the George Floyd Rebellion, which always converged in their paranoid belief that everything that happened that summer was the act of some opportunistic and sinister outsider. Did Rittenhouse act in self-defense? Maybe–I don’t give a shit. Did he act without thought, kill two people and wound another? Yes. Do you want a teenager to die in prison? Not really, but god, fuck him. I don’t know. The story is a tragedy that our conspiracy theories can’t handle. The painful ethical question is: would it have been better that Kyle Rittenhouse met judgement that night, outside the law? Maybe, no? I don’t know. Two people would still be dead. The tragedy might have been felt more clearly, the cosmos more balanced in trauma, and maybe some people would have reconsidered how many pounds of flesh they were willing to sacrifice.

Citizen Police

In crucial times during this civilization’s decline, where the state risks losing control and its softer policing proves ineffective, governments will step into the role of orchestrator. They will restore raw violence and mobilize citizens to kill each other. Nationalism and progressive civil duty will be both summoned to ward off the bogeymen. Each provides for those who want antiquated “security”–the narrative to justify their racial, social, and economic anxieties. Here, the image of civil war functions as a pornographic fantasy for cleansing the land. In reality, any armed conflict in this country will be multipolar.

The outsourcing of force from the state to the citizen is happening amid an accelerated unravelling of the US, a social fabric deeply polarized by cultural issues, a pandemic racking up bodies, and the collapse of the global consensus set in place after World War II. The violence that is coming, and to which our political sensibilities are being attuned by the rhetoric of civil war, carries in it a series of traps. It’s not a decisive battle between freedom and fascism, but a parenthesis between liberalism and technological governance.

In a democratic society, the ability to decide on life or death and the exception to the law is given over to the police, whose peculiar economic function is to reduce surplus populations through killing or incarceration. Neoliberalism turns the modern state inside out. All the while, the state contorts itself to the demands of technological progress. As police capacity for excessive and lethal force is formally reduced–whether by market necessity, popular demands, or unpredictable crises–it will be structurally diffused to the citizen and private sector. The archaic and irrational racist violence of police unions is already beginning to give way for the more technically sophisticated data-driven policing of the future.

Like other redundant institutions replaced by apps, the defunded police will be increasingly unable to perform their public function and will serve only as an empty avatar, while control is spread out across a series of private and technological solutions. In the future Big Tech has in store for us, police will function less like a militarized occupying force and more like a user-interface component in urban environments refashioned as a web of predictive user experiences, and subject to the principle of a generalized traceability. The future of policing will consist in getting a push notification on your cell phone asking “Are you sure you want to steal that?” Since everything you do will have been captured by the archive, the vulgar face of power can be replaced at no cost with officers trained to ask your preferred pronoun while putting you in a pain compliance hold.

Like other redundant institutions replaced by apps, the defunded police will be increasingly unable to perform their public function and will serve only as an empty avatar, while control is spread out across a series of private and technological solutions. In the future Big Tech has in store for us, police will function less like a militarized occupying force and more like a user-interface component in urban environments refashioned as a web of predictive user experiences, and subject to the principle of a generalized traceability. The future of policing will consist in getting a push notification on your cell phone asking “Are you sure you want to steal that?” Since everything you do will have been captured by the archive, the vulgar face of power can be replaced at no cost with officers trained to ask your preferred pronoun while putting you in a pain compliance hold.

The real trial of the epoch is how to fight and win a different war.

Give and Take

After the long 2020, the stakes feel higher. Kenosha rings in my ear every time I fire my AR. The fatal summer returned a specter of force to newscycle politics, with the pandemic a constant reminder of the fragility of it all. The lead lines in America continue and we’ve all joined the fray.

There is one not-so-distant future where all the hundreds of millions of arms in the US, all the new leftist-owned gun stores, all the LARPing in plate carriers and practicing cover fire and close quarter combat drills, will give rise to an even bloodier situation than unfolded in 2020. If the liberalism at the heart of American gun ownership continues to infect and poison the growing ‘“leftist” gun culture, then disaffected teenagers sympathetic to the left may be swayed to commit similar nihilistic atrocities as that of their 8kun counterparts. This is not the terrain we want to fight on. In this future, violence continues to be pornographic and the ethical questions at the heart of using force go unanswered.

If our image of war cannot break with a fantasy of annihilation, we will always find ourselves struggling to grasp a tragedy of our own making. Is there instead a world where we don’t flee from violence–where warriors are called to war–but where that disposition toward death is an extension of our celebration of an excessive and exuberant life? How can we face the dark future that lies ahead with sobriety, while continuing to celebrate the spirit of May 28, the night the Third Precinct burned?

In some ways, the leftist gun culture that has grown since 2020 centers itself on its political weaknesses rather than the strength of technique. While it’s true that “we keep us safe,” picking up arms changes your orientation to the world in ways more fundamental than the capacity to protect oneself or your community. You have to live with the capacity of violence–an appendage that was supposed to be amputated from us long ago. You have to be responsible and tend to this capacity, exercising your technique, cleaning and maintaining your arms, and refining your talent. Likewise there is something that reaches far beyond where you position a muzzle. How to use a technique is an ethical question. Answering this in practice attaches you to a world. This attachment is how technologies also always use us. We don’t only need to add plate carriers and night vision goggles to our repertoire to prepare for civil war–an impulse that life-taking technologies rush us toward. Instead, a robust dwelling in the world of arms might mean to also see through the gun to its otherside: life-giving. We owe it to the next generation to teach this, to tell stories, and to demonstrate how learning to tend to our power is the result of gratitude to an earth that nourishes us. The hunter knows this, as do the war councils of the Haudenosaunee. What is hidden by the glowing figure of the armed combatant is the earth on which she stands.