A lively debate has ensued over the merits of the film, Don’t Look Up. People on the progressive side of the political spectrum have praised the film for its piercing honesty about the climate crisis which is communicated through the metaphor of an incoming, planet-destroying comet. In the film, establishment politicians and their corporate donors lack interest in the crisis and opportunistically search for ways to both avoid controversy and profit from it. The state is brutal toward those who speak out against powerful elites and is readily prepared to enact violence and/or sabotage against the people. Corporate celebrity and social media culture is highlighted as a powerful distraction which coerces the masses to “look down” rather than confront the pressing problems facing humanity.

It was inevitable that these elements of the film would make it a target of bad-faith criticism from the corporate media. Don’t Look Up has been subject to hostile critics seeking to delegitimize the film’s worldview. A CNN review unironically accuses the film of politicizing science and condemning the very people that need to be convinced about the climate crisis. The San Francisco Gate ignored the film’s metaphor for climate change and corporate destruction all together, arguing that the government could never keep a secret about a crisis so significant as a planet-destroying comet. MSNBC, to no one’s surprise, took issue with the film’s portrayal of the corporate media and its role in shifting attention away from the climate crisis at the behest of establishment politicians and corporations.

The film obviously did something right to receive a flurry of negative reviews from the capitalist press. Don’t Look Up embarrasses elites and convincingly exposes their opportunism through satire. The relationship between U.S. President Janie Orlean and mega campaign donor/tech capitalist Peter Ishawell offers a clear presentation of the relationship between corporate power and politics in the United States. Ishawell asserts his influence on numerous occasions to ensure that President Orleans’ policies benefit his bottom line. Everything is subordinate to Ishawell’s lust for profit, from predictions about death to the illustrious natural resources that reside on a comet that threatens to eliminate life itself. The normalcy with which Pentagon General Stuart Themes charges the group of scientists for free snacks is one of several humorous examples where Don’t Look Up demonstrates the detestable behavior of the self-serving ruling class.

Overall, there were aspects of the film that I enjoyed and others that I didn’t. Dr. Mindy’s descent into celebrity was an entertaining example of how no amount of access to the capitalist class can change a system under its firm control. President Orleans’ expression of a hybrid Trump/Clinton political identity was an equally entertaining window into the corruption-ridden social character of the U.S. political system. Unfortunately, the film fell into the many perils of Western liberalism. Director Adam McKay clarified the liberal politics of the film when he pronounced that “awareness, will, and action” (and labs, apparently) are what’s needed to solve the climate crisis.

Overall, there were aspects of the film that I enjoyed and others that I didn’t. Dr. Mindy’s descent into celebrity was an entertaining example of how no amount of access to the capitalist class can change a system under its firm control. President Orleans’ expression of a hybrid Trump/Clinton political identity was an equally entertaining window into the corruption-ridden social character of the U.S. political system. Unfortunately, the film fell into the many perils of Western liberalism. Director Adam McKay clarified the liberal politics of the film when he pronounced that “awareness, will, and action” (and labs, apparently) are what’s needed to solve the climate crisis.

It’s quite clear in Don’t Look Up that McKay and company are primarily concerned with raising awareness of the climate crisis through a liberal lens. The protagonists, two scientists, go on a crusade to convince the establishment to solve a crisis that will literally take down the entire planet. While climate change certainly mirrors this kind of crisis, the way that we go about addressing it is always a reflection of politics. The film emphasizes a struggle between a noble scientific community and an ever-resistant, short-sighted elite. People’s movements receive very little attention in the and when one emerges it is reduced to a hashtag campaign that does little more than spread awareness of the crisis at hand.

This sends a cynical message to viewers that while powerful elites are the root of all problems, they are also the only force capable of stopping the comet (climate) crisis or any other malady of capitalism. The distracted and alienated masses may rise up in rebellion and pressure politicians to behave differently but in the end it just isn’t enough to alter the trajectory of the system. In the U.S. context, there certainly is truth to this assumption. The U.S. left has been violently suppressed by the state, the consolidation of state power around endless austerity and war has produced unprecedented levels of despair and alienation, and movements such as Black Lives Matter, the environmental movement, Occupy Wall Street, among others have been unable to forestall capitalism’s Race to the Bottom.

Still, history is FULL of examples that demonstrate people’s movements are the only hope for humanity to come out of any crisis, climate change included. The global working class movement inspired by the Russian Revolution literally set a standard of social welfare and security throughout the so-called “developed” world amid a period of war and economic depression. The Black liberation movement created an example of people’s democracy in the United States until its destruction beginning in the 1970s. Social Security, Medicare, the right to form a union, and many other key staples of what is left of the welfare state are byproducts of social movements, mainly led by communists, which pressured the power structure during times of crisis to enact reforms or face a revolutionary situation. Liberals have always struggled to shed their dual loyalties to the establishment and it shows in the marginalization of movement politics in Don’t Look Up.

Perhaps even more indicative of Don’t Look Up’s liberalism is its cynical depiction of global politics. Russia, China, and India only respond to the planetary crisis when the U.S. cuts them out of a deal to mine the comet’s precious resources. The film references a “President Qi” of China (a not so subtle jab at Chinese President Xi Jinping) who is said to have communicated to the world the failed attempt by the BASH corporation to push the comet off its trajectory by, er, using drones to plunder it of resources. China and other major powers are thus portrayed as no better than the United States. U.S. elites represent the only hope for humanity—a clear ideological concession to American exceptionalism.

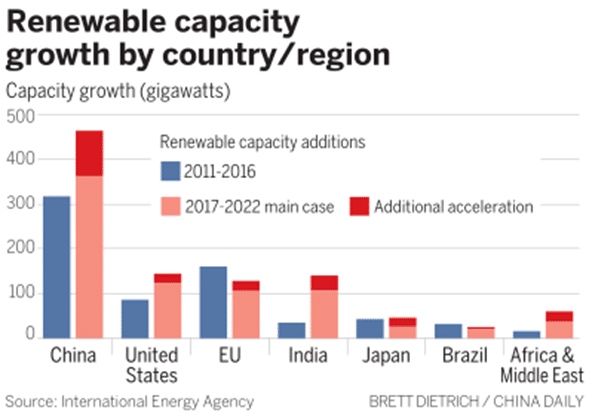

The facts in real life tell a different story. Take China, for example. China is a world leader in renewable energy and is set to become carbon neutral by 2060, the fastest path to carbon neutrality of any major power in history. There is no political faction in China that denies climate change and Chinese officials have been forthright in cooperating with the U.S. on climate issues despite facing innumerable hostilities. China finds itself surrounded by more than fifty percent of the U.S.’s military, one of the biggest polluters on the planet , and sanctioned economically and diplomatically. This includes sanctions on a major solar producer in Xinjiang on questionable human rights claims, a policy that directly hampers the world from addressing the climate crisis.

The facts in real life tell a different story. Take China, for example. China is a world leader in renewable energy and is set to become carbon neutral by 2060, the fastest path to carbon neutrality of any major power in history. There is no political faction in China that denies climate change and Chinese officials have been forthright in cooperating with the U.S. on climate issues despite facing innumerable hostilities. China finds itself surrounded by more than fifty percent of the U.S.’s military, one of the biggest polluters on the planet , and sanctioned economically and diplomatically. This includes sanctions on a major solar producer in Xinjiang on questionable human rights claims, a policy that directly hampers the world from addressing the climate crisis.

Furthermore, there is no evidence that China would sit on its hands waiting around for the U.S. to cut a deal before acting on a major planetary crisis. China has repeatedly demonstrated a strong capacity to quickly respond to domestic and global crises. Amid the detection of the novel coronavirus that would become the COVID-19 global pandemic, China produced a genome for the world within eleven days and built two massive hospitals within weeks to treat and isolate the infected. The rapid and people-centered character of China’s pandemic response saved upwards of 950,000 lives according to Chinese epidemiologists. Additionally, China eliminated extreme poverty in just seventy-one years after its 1949 revolution overthrew the semi-colonial and imperialist-dominated system that made the country one of the poorest in the world for more than a century.

Of course, the film isn’t about China. That doesn’t mean an opportunity wasn’t missed to forward a politics of global solidarity, something that is missing entirely from a Hollywood industry completely wedded to the U.S.’s military industrial complex. Don’t Look Up repeats anti-communist prejudices characteristic of the Western liberal “left.” The Western liberal “left” generally ignores or slanders oppressed nations targeted by U.S. imperialism in a manner characteristic of the U.S. State Department. This is especially true for those countries who dare to chart their own course of history independent of imperialism such as Cuba, China, Bolivia, the DPRK, and several others.

In the end, Don’t Look Up reflects the generalized cynicism of U.S. capitalism in decay. The good news is that the film offers an entertaining and broadly useful analysis of U.S. social relations even if the existence of the working class is largely excluded from the film. The bad news is that people’s movements and global solidarity, two critical elements of any struggle against the climate crisis, are either marginalized or left out of the film all together. It would be silly, however, to expect a Hollywood film to point the way forward in the struggle against U.S. capitalism. Don’t Look Up should thus be viewed as an opportunity to engage in the debates that will raise the people’s consciousness to a higher level and encourage further participation in movement politics and class struggle.