Critical race theory (CRT) is being attacked by the far right all around the country, with angry opponents filling school-board meetings. Florida, Tennessee, Idaho, Iowa, Arkansas, New Hampshire and Oklahoma have already banned or restricted its presence in the classroom, and 16 more states are currently debating whether to enact similar laws. A California school-board president told Fox News last August that CRT is trying to “drive a wedge between various groups in America, various ethnic groups, and to use that to absolutely ruin our nation.”

CRT supporters’ principal defense has been to claim that its opponents are simply ignorant: they don’t know what critical race theory is, or that it is only taught in law schools. New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote in his Jan. 24 column that CRT “isn’t actually being taught in public schools.” MSNBC pundits have called it a “unicorn.” This just feeds the sense that “liberal elites” take the hoi polloi to be uneducated birdbrains.

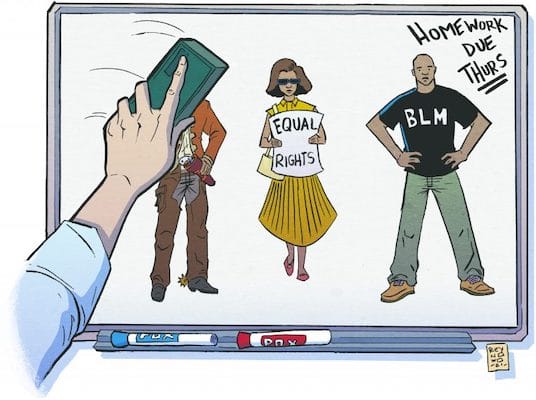

Fox News, despite its efforts, is not capable of making unicorns look like real horses. The opponents of CRT know that it claims that structural racism is embedded in U.S. history and current institutions. This topic is playing out in public classrooms. Teacher training for some years has beefed up segments on teaching racism; unlike a generation ago, textbooks today cover the history of slavery in some depth. Readily available classroom resources include units on racism and police violence, whiteness and the Black Lives Matter movement.

If the youth of this country are regularly exposed to such content, they will begin to ask questions, and their patriotism may be at risk. In the best-case scenario, this could lead to a more multiracial democracy than we have ever had.

We need to recognize that this is a serious and legitimate debate. How do we create a meaningful democracy when large groups of people have such different historical relationships to the country? Thomas Jefferson suggested that slaves should be sent back to Africa after slavery was abolished, because he didn’t believe a united political community could be formed given the enmity slavery caused. But we haven’t given building that kind of community a real try yet.

The current debate over CRT is an opportunity. The hardier of us should enter these Parent-Teacher Association and schoolboard meetings and organize more venues for open discussion. Invite the press; arrange for regular white folks (i.e. not professors) to speak to the issue; offer a reasoned counter-view to the U.S.-can-do-no-wrong cheerleading; address concerns about children’s mental well-being with empathy; and complicate the category of “whiteness” with intersectionality.

Here are some suggested dos and don’ts:

1) Stop denying that critical race theory is being taught. Yes, strictly speaking, CRT began as an approach to reading legal judgments for their subtle racism. But the concept is now being used interchangeably with any attempt to grapple with slavery, colonialism, genocide and racism in the history of the United States. Opponents of CRT are concerned that addressing these histories will bring the country down, that it means cultural suicide. To counter this with simplistic logic is inadequate and even offensive: People need hope, a motive for patience and the ability to participate meaningfully in reframing their own understanding of who they are and who we together might become.

How do we create a meaningful democracy when large groups of people have such different historical relationships to the country?

2) Explore ways in which the past matters today. European and U.S. empire-building created the world as it looks today. Cumulative advantages accrue across generations even in the absence of racist intent. But the past is not all one unending story of crime and horror. We can also find moving stories of resistance in our national history, which can plant seeds of hope and inform concrete agendas. This country forfeited a huge opportunity for moral and political advance when Reconstruction was dismantled; studying that period and others can help us chart a way forward.

3) Admit that whites may experience these new educational initiatives differently. An important aspect of white American identity is the “American identity” part, as Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s recent gaffe indicates. For many, “America” connotes concepts like world leader, democracy and a charitable people. It looks different when we consider slavery, the genocide against Native Americans or the bloody imperial ventures that the United States has embarked on. Many white individuals are scared of blowback. But we need to think beyond individual responsibility, as CRT explains, and we need to recognize that we are all connected in some way, whether biological or not, to some pretty great people and traditions. We have many elements to build on as we revise the country’s history. We can still have peaceful parks and neighborhoods, integrated schools that sometimes work well, and a sense of compatibility despite differences in the music we like or the religion we practice. We need to find those persons in our family tree, or those who simply share our ethnic or national identity, whom we can genuinely honor.

4) Don’t assume that guilt and shame have no positive role to play. This has been a dysfunctional assumption on the left, though it is often a reaction to dysfunctional practices. White guilt and shame can turn the focus onto white people’s feelings rather than toward racial justice. Yet these emotions a) are inevitable, b) are indicative of a functioning moral conscience and c) can, at least some of the time, motivate changed behavior. Do I want my grandchildren to go through this reckoning again because I didn’t have the courage to? No. Do I feel shame if I find a relative who played a bad role? Of course. Feelings are not irrelevant to political change, but quite central. We need to stop ridiculing the “psychological anguish” white parents express, and make spaces to express and explore these feelings without quick pedantic responses.

5) Go on the offense with a substantive counter-narrative. This is the most important point. By denying that CRT is being taught, we lose the ability to offer a different spin on the lessons of our national history. The way forward is not through social engineering by upper-class white liberals, but by real grass-roots participation. There is a lot to build on, in the public-school system, the union movement, traditions of religious pluralism, commu- nity organizations (particularly around schools) and small-d democratic practices. We need to connect the dots between race and class without minimizing either one, as Ian Haney- Lopez argues in his recent book, Merge Left. Neither color-blind class politics nor antiracist agendas that downplay class will shift the country’s politics. The far right is endangering the future of the country; but as the Peruvian theorist Jose Carlos Mariategui argued in the 1920s, a rising fascism is the fruit of the failures of the left.

This is an important fight. Even if the bans are defeated, teachers will second guess their curricular choices for fear of controversy. Graduate students I have worked with are already reconsidering their pursuit of research areas that may generate death threats and cost them jobs. Some people oppose bans because they oppose outright censorship, yet still dislike the teaching of CRT, and such sentiments will no doubt continue to spread the movement against it.

We need to get this right.

Linda Martín Alcoff is a professor of philosophy at Hunter College. She is the author of The Future of Whiteness (Polity, 2015).