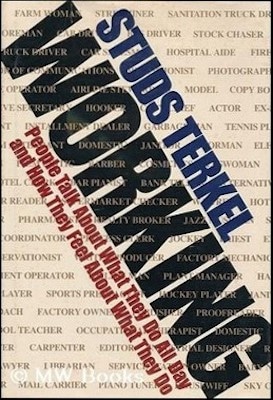

As I prepared to teach my module on work this year, I realised that Studs Terkel’s book Working celebrates its fiftieth anniversary in 2022. It’s a book that both reflects and helps to explain working-class life. I first encountered it as a student, and in the passing years Working—or to give it its rarely used full title Working: People Talk About What they Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do–has shaped profoundly the way I think and teach about work.

First published in January 1972, Working is a baggy collection of over seven-hundred and sixty pages, most devoted to the reflections of ordinary Americans about their economic lives. From the Terkel archive, it’s clear that his interest in work was long standing and went well beyond the USA.

I know the book well, but in writing this piece I leafed through it again to think about the changing nature of work across that half a century. I thought it might really be showing its age–after all, fifty years is a long career. Instead, I was reminded how vital Working is. To my surprize, many of the jobs and occupations Terkel asked about in his interviews still exist: receptionists and police officers, spot welders and carpenters, factory owners to waitresses and so on. For sure, the technology that workers use in their jobs has changed. Few of the people in the pages of Working in 1972 would have seen a computer, less likely used one. But it’s harder than you might think to see obsolescence here.

Working remains fresh because Terkel’s humanity and warmth comes through on virtually every page. His character as well as his approach to the art of interviewing are artfully captured in his introduction. Just seventeen pages long, the essay sums up for me what is most important about work – people. As he puts it beautifully:

It’s about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying. Perhaps immortality, too, is part of the quest. To be remembered was the wish, spoken and unspoken, of the heroes and heroines of this book.

Terkel captures the timeless quality of the profound contradictions of work, especially a worker’s sense of loving and hating work in the same moment. This may be true of all kinds of work, but it seems especially important in working-class labour. In an interview about Working, Terkel described how a meter reader he talked to spoke about the reality and fantasy of his work. While reality demanded that he be constantly vigilant for dogs, he also fantasized about female encounters on his rounds. As Terkel puts it, ‘it makes the day go faster’.

Studs Terkel’s ability to put his subjects at ease was legendary. I once heard a story about Terkel confronting a burglar in the process of robbing his home one night. The story goes that rather than call the cops, Studs sat the intruder down on his couch and started to interview him about his working life. I’m not sure of the veracity of the story, but I really want it to be true!

I use Working in many ways in my teaching, most obviously in classes on work. My students warm most to Terkel’s interest in the extraordinary nature of ordinary everyday life. They recognise his ability to see through the shallowness of the dramatic, showier aspects of contemporary life and his interest in the capacity of ordinary people to live their lives. As he says in his introduction:

I realised quite early in this adventure that interviews, conventionally conducted, were meaningless. Conditioned clichés were certain to come. The question-and-answer techniques may be of some value in determining favoured detergents, toothpaste and deodorants, but not in the discovery of men and women. There were questions, of course. But they were casual in nature-at the beginning: the kind you would ask while having a drink with someone; the kind he would ask you. The talk was idiomatic rather than academic. In short, it was conversation. In time, the sluice gates of dammed up hurts and dreams were opened.

Terkel is also a model for would be interviewers. It took me a long time to realize just what a great skill it is to be able to get people relaxed enough to talk about those ‘hurts and dreams’—especially working-class people. Middle-class people often seem to feel entitled to be interviewed. They believe they have something worthwhile to say or that their lives obviously matter. By contrast, I’ve lost count of the times a potential working-class person modestly deflected my request for an interview, asking ‘why do you want to talk to me? I’m just a . . . ’.

Since its publication in the early 1970s Working has constantly been in print, but has also spawned adaptations, including guides for using the book in the classroom and Working: A Graphic Adaptation by Harvey Pekar and Paul Buhle. In the late 1970s, the book was the basis of a musical, and there have also been acting workshops and recently a theatre project in Washington DC staged an updated version that included references to the pandemic.

We need to think more about new forms of work, and interviews can help us do that. Gig workers and others will tell different stories than we find in Working, but at the heart of their narratives, we may also hear similarities. It’s always been important to listen to the voices of those who work. Sometimes they reinforce our perceptions, but often they confound them in unexpected ways. Almost always, when one talks and, perhaps more importantly listens to what people have to say about their work, we learn about them and ourselves. Above all, we recognise what was at the heart of Studs Terkel’s own working life, the quest for meaning and humanity in all the people he spoke to.