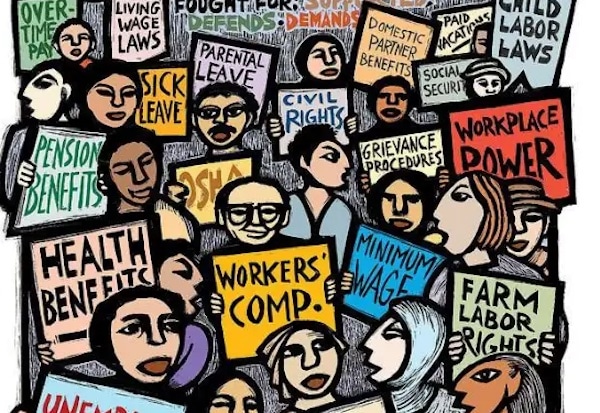

This past year, profit-over-people ideology and anti-union efforts were particularly prevalent in the sectors that demanded the most labor. Millions of dollars went into campaigns to stop union organizing at the same time that several anti-worker policies passed into effect, painting a grim future for workers across the U.S. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is the single most important federal entity where workers can supposedly go for legal protection. In recent years, particularly following the Trump Administration’s maneuvering, pro-corporate appointees and anti-labor judges have taken over the NLRB.

This past year, profit-over-people ideology and anti-union efforts were particularly prevalent in the sectors that demanded the most labor. Millions of dollars went into campaigns to stop union organizing at the same time that several anti-worker policies passed into effect, painting a grim future for workers across the U.S. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) is the single most important federal entity where workers can supposedly go for legal protection. In recent years, particularly following the Trump Administration’s maneuvering, pro-corporate appointees and anti-labor judges have taken over the NLRB.

Late capitalism has exposed the drastic inequalities inherent to our neoliberal economy. While mega billionaires got richer from COVID, millions of Americans suffered excessive levels of debt, unemployment, poverty, and overwhelming loss. These are clear violations of people’s human rights–all the while, corporations’ anti-worker agendas continue to charge powerfully forward.

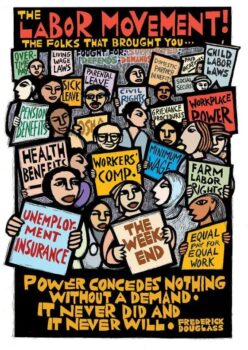

This past year in labor set a concerning precedent for the future of workers across the country. The union-busting and structural policy changes that have taken place are on track to pressure unions to prioritize the interests of their employers over the rights of workers. The power of corporations over working people is being cemented into policy as we speak to further promote the exploitation of workers and obstruction of unionizing efforts. Our only way out is for workers to gear up for the fight of their lives to push back against these building blocks of corporate interest.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2021 report revealed the effectiveness of corporate anti-union tactics. The report showed 241,000 fewer union members than the previous year, which means just 1 in 10 workers are part of a union. In the private sector, it’s 1 in 16. Without a sturdy base, unions are no match for the union-busting strategies of their employers.

Labor exploitation & union-busting: the case of Amazon

Amazon, often referred to as the white whale of the labor movement, is among the most notorious union-busters today. Still, when an Amazon warehouse opened in Bessemer, Alabama in 2020, it took a little under a year for workers to push for a union election. Among their reports were descriptions of abusive productivity expectations across the frenzy-filled pandemic summer. The Amazon behemoth is the world’s fourth-most-valuable company, and Jeff Bezos, its founder, is the world’s richest person. Amazon employs a little over a million people and is the top American ecommerce platform. It’s an example of what a successful business model looks like in the 21st century. It’s also a temperature check for labor conditions today.

As fundamentally anti-worker and pro-corporation, Amazon’s priority is first and foremost to increase worker productivity and lower labor costs, which is done by tracking its workers’ every movement. Externally, In Bessemer, Alabama, Amazon touts paying workers double the minimum wage, which in the state is $7.25, but internally, workers struggle to meet the demand let alone get their basic needs met. Until this past year, little public attention was paid to the working conditions fostered by Amazon. The Bessemer Amazon workers changed the name of the game by calling attention to the drastic conditions they are expected to work under. Workers revealed urinating in bottles while on their shift because they don’t have time to use the bathroom. This goes beyond inhumanity, and points to the lengths that Amazon will go to in order to control workers and guarantee rapid fulfillments.

The worker-led unionizing campaign that arose at the end of the summer sparked a lot of attention because it was in the South and because organizing within Amazon was unexpected. Immediately following the announcement that workers would push to unionize the warehouse, Amazon shot back with an anti-union campaign, employing several aggressive tactics to discourage unionization. This included hiring anti-union lawyers, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, forcing employees to sit through mandatory meetings that emphasized the company’s anti-union position, anti-union signage such as “Vote No” signs in bathrooms, and pestering workers while in the workplace.

The “just and favorable” working conditions defended in Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) are far from represented at the Amazon Warehouse in Bessemer. And yet, organizing workers to fight union-busting proved to be incredibly difficult. Though Amazon workers are still in the process of pushing to unionize the Bessemer warehouse, their severe working conditions have not decreased. Neither has the union-busting for that matter. Targeting workers from the most in-demand sectors ensures that millions of workers remain submissive to their employer’s control.

The sustained anti-union agenda

Efforts to quell union organizing are not only prevalent in newer work sectors; in fact, one of the longest strikes of 2021 featured workers from a coal mine in Brookwood, Alabama. On April 1st, 2021, 1,100 union coal miners in Brookwood, Alabama began striking against the unjust labor practices headed by Warrior Met Coal. Mining in Alabama dates back to the nineteenth century. The miners at Warrior Met who carry on that history, working under grueling conditions with long-lasting effects on their health and physical well-being, are demanding a new and fair contract that includes better pay and more time off.

Warrior Met Coal is a multi-million-dollar coal mining company. It was founded to buy the assets of Walter Energy after it declared bankruptcy in 2015. Workers took on cuts to wages and benefits in the aftermath, but were promised to regain their income and then some once the company regained solvency. The United Mine Workers of America (UMW) have calculated that as per their agreement with Warrior Met, the miners are owed over $1.1 billion in pay and other benefits.

In 2021, Warrior Met Coal reported a net income of $150.9 million. Last December, the company hired the firm Sitrick and Company to improve its public image. One of its tactics was to launch a smear campaign against the miners by feeding stories to the press that described the miners as lawless and violent. At the same time, multiple miners who were striking were hit by cars and trucks driven by company employees while they were on the picket lines. Warrior Met’s publicity team also created a Twitter account called WarriorMetCoalFacts that includes videos and written posts painting miners in a bad light while uplifting the image of the company.

The unionists have been on strike for over 10 months. This has presented many financial struggles for the miners and their families, and they have seen little to no headway or success. The human right to fair payment, to equal pay for equal work, as stipulated in Article 23 of the UDHR, is not being realized by any means. At Warrior Met Coal, workers are permitted to have a union since they are employees, but their union is not respected, nor is it protected from attacks by its employer. These are clear violations of workers’ human rights.

Exploitation in the gig economy

Workers for food delivery services and rideshare drivers for billion-dollar corporations like Uber, Lyft, and GrubHub were in high demand this past year. They were also some of the most neglected workers to date, regularly robbed of their most basic human rights. The onset of the gig economy has normalized short-term labor contracts that disallow unionizing, paid time off, hazard pay and other significant benefits. Short-term labor contracts and the hiring of workers as independent contractors lets corporations sidestep nearly all of the responsibility and cost that is fundamental to protecting employees. It essentially dismisses corporations from being held accountable for overworking their workers.

The gig economy’s normalization of protocols that violate workers’ best interest and dismiss their right to protest against such protocols is disturbing and sets a concerning precedent for the future of labor law. Any employer that withholds the right to a safe and dignified work environment is violating workers’ fundamental human rights. Gig workers are prevented from organizing themselves, another tactic aimed at undermining their autonomy.

Anti-worker policy-making

In addition to the union-busting and anti-worker organizing by corporations, there has also been the strategic effort to cement policies within the structural framework of today’s labor force that prioritize corporate interest over workers’ rights. Once anti-worker policies become part of labor law, violations against the rights of workers will become next to impossible to regulate. Two major labor policies pushed forth in 2021 were Proposition 22 and the Protect the Right to Organize or PRO Act.

In a win for Californian gig workers, lawmakers passed legislation called AB5 that reclassified gig workers as employees in 2020. The legislation meant that gig companies would no longer be able to classify their workers as independent contractors. If gig workers were required by law to be hired as employees and not contractors, then these companies would have to increase their expenses to accommodate employer-paid insurance, unemployment insurance, severance, and reimbursements for fuel and other job-related costs. The reclassification of gig workers as employees would obliterate the gig economy’s business model.

Corporate concerns over the passing of this legislation were, as you might imagine, profit-oriented. Immediately following the legislation announcement, Uber and Lyft, among other app-based companies, launched a $200 million campaign to support a ballot initiative called Prop 22, that would exclude them from that law. Their campaign included “Vote Yes” ads that told voters consumer prices would rise and that drivers would suffer if the initiative did not pass. Their campaign was successful; the measure passed, and all gig companies in California raised their prices regardless of what they had previously promised voters.

The Prop 22 ballot measure allows corporations like Uber to continue treating workers as independent contractors. It also incentivized businesses such as the California grocery chain, Albertsons, to lay off their in-house unionized delivery drivers and hire DoorDash contractors instead. According to Idrian Mollaneda from the California Law Review, “Proposition 22, financed almost entirely by gig companies, is a case study in how businesses can purchase new laws.” The win for gig companies in California will likely spread across to the rest of the country, a prospect for the future of the anti-worker policy-making agenda.

Victories of the labor movement

The PRO Act is the most important and encouraging policy to be introduced to labor law in a long time–maybe ever, when considering the contemporary issues of the gig economy. If passed, the PRO Act would provide significant labor protections for all workers and restrictions against labor misclassification. The PRO Act would also strengthen unions, protect the right to strike, and protect digital organizing. Via this policy, the rights of workers recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights would be propped up and promoted through a policy that puts their human rights first.

While passing the PRO Act should continue to be an immediate priority, it certainly isn’t enough to transform the labor movement in the U.S. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the PRO Act will pass soon, when considering the excessive lobbying power that corporations have to dictate legislation. Only an organized labor force can fundamentally shape the conditions of workers in the U.S.

This past March, following two years of organizing, workers at an Amazon warehouse on Staten Island voted to unionize and become part of the Amazon Labor Union (ALU), a historic and monumental win for the e-commerce labor movement and one of the largest labor forces in the world. Immediately following this landmark win, unionization efforts at other Amazon locations in New York City began snowballing. The success of this worker-led struggle against the Amazon behemoth carries important stakes for the future–most notably, the question of whether workers’ ability to build a revolutionary labor movement is possible.

We need all-hands-on-deck, worker-led organizing. We need motivated unionizing efforts to continue. We need consistent worker-to-worker solidarity. And we need voters to read the legislation and advocate for policies that will uplift workers’ rights. The issues workers are confronting today have nothing on the issues workers will confront in ten years if we don’t do our best to stop the institutionalization of labor laws that undermine workers’ rights and democracy, and build working class power from the bottom up.

References

Bradbury, A. (2021, December 17). 2021 Year in Review: The Only Way Out is Through. Labornotes.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from labornotes.org

Bergfeld, M., & Farris, S. (2020, May 10). The COVID-19 Crisis and the End of the “Low-Skilled” Worker. Spectrejournal.com. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from spectrejournal.com

Communications Workers of America. (n.d.). Trump’s Anti-Worker Record. CWA-union.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from cwa-union.org

Groves, D. (2022, April 1). Warrior Met Coal Strike Hits One-Year Mark. Thestand.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.thestand.org

Hern, A. (2020, January 29). Gig Economy Traps Workers in Precarious Existence, Says Report. Theguardian.com. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.theguardian.com

Kelly, K. (2021, October 27). Warrior Met Coal’s New PR Strategy: Smearing Striking Miners. Patreon.com. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.patreon.com

Lake, R. (2022, January 9). What was California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5)? Investopedia.com. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.investopedia.com

Leon, L. F. (2021, August 10). Striking Alabama Coal Miners Want Their $1.1 Billion Back. Labornotes.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.labornotes.org

Mollaneda, I. (2021, May). The Aftermath of California’s Proposition 22. Californialawreview.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.californialawreview.org

Rosenberg, J. (2020, November 4). Uber and Lyft Just Bought Their Way Out of Employing Drivers. Motherjones.com. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.motherjones.com

Savage, L. (2021, May 13). Corporate CEOs Won the Pandemic. Jacobinmag.com. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.jacobinmag.com

Streitfeld, D. (2021, April 5). Amazon’s Clashes with Labor: Days of Conflict and Control. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.nytimes.com

United Nations. (n.d.). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. UN.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from www.un.org

Warrior Met Coal. (2022, February 22). Warrior Met Coal Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2021 Results. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from investors.warriormetcoal.com

Zhang, S. (2021, July 22). Over 40 Progressive Orgs Unite to Pressure Congress to Pass Pro-Union Pro Act. Truthout.org. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from truthout.org