This is the first in a series of posts on the future of work since the pandemic slump.

A few weeks ago, the world’s richest man Elon Musk, Tesla CEO, told his employees that they must return to the office or get out of the company. Musk wrote in an email that everybody at Tesla must spend at least 40 hours a week in the office. “To be super clear: the office must be where your actual colleagues are located, not some remote pseudo office. If you don’t show up, we will assume you have resigned.” He then went on to praise workers in his Chinese factories for working until 3am in the morning if necessary.

In 2021, Goldman Sachs’s chief executive, David Solomon, said “remote work is not ideal for us, and it’s not a new normal”, and predicted that it would be “an aberration that we’re going to correct as quickly as possible”. A year later, however, less than half the bank’s employees were regularly turning up to its New York headquarters, forcing Solomon, to again plead with staff to come back. Again last year, Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan Chase’s chief executive, said working from home “doesn’t work for spontaneous idea generation. It doesn’t work for culture.” Dimon finally relented and said 40% of the bank’s 270,000 employees could work as few as two days a week from the office. In his annual letter to shareholders, he said “it’s clear that working from home will become more permanent in American business”.

Musk and these other bosses are like King Canute trying to turn back the tide. Since the pandemic, many workers are refusing to return to a full-time five-day week. More than a third of the UK’s office-based workforce is still working from home. In the UK, 23% of workers earning £40,000 or more are still working from home five days a week and a further 38% are in a hybrid pattern, splitting their time between the office and home.

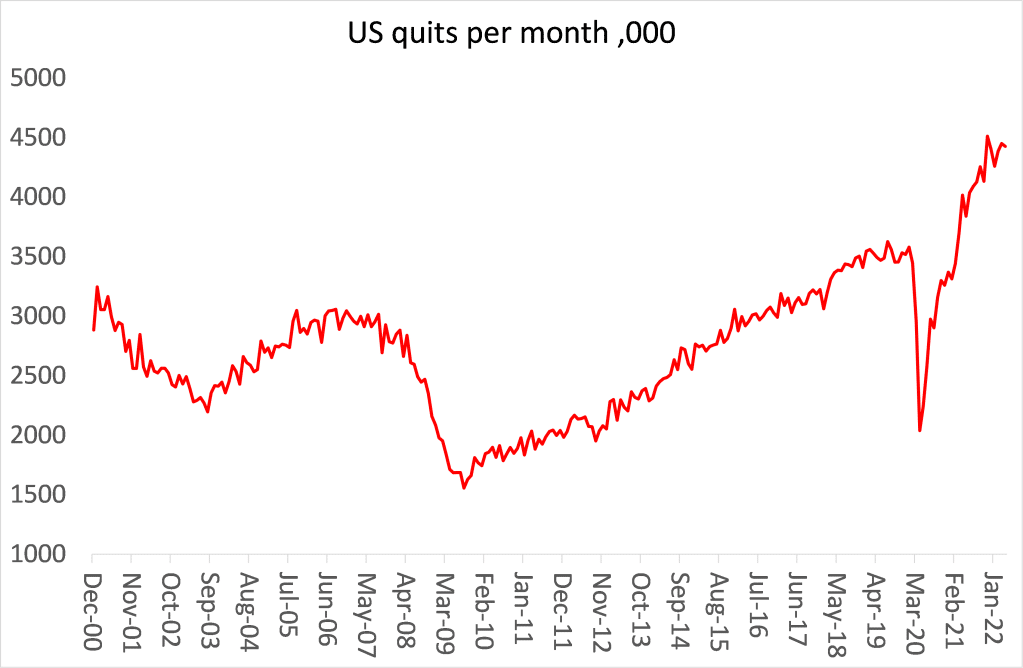

Since the pandemic there has been the phenomenon of the so-called Great Resignation. The Great Resignation is the idea that a large number of people are quitting their jobs, and doing so because the pandemic gave them new perspective about their careers or were burned out during the pandemic. A Microsoft global survey of more than 30,000 workers showed that 41% were considering quitting or changing professions, and a study from HR software company Personio of workers in the UK and Ireland showed 38% of those surveyed planned to quit in the next six months to a year. In the U.S. alone, April saw more than four million people quit their jobs, according to a summary from the U.S. Department of Labor–the biggest spike on record.

This is not a uniquely American phenomenon. China’s “lie flat” movement, in which young people are turning their backs on the daily grind, is gaining popularity. In Japan, known for long office hours, the government has proposed a four-day working week.

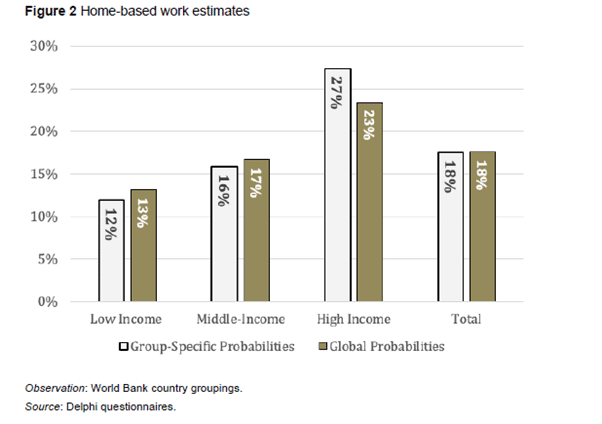

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ILO estimated that 7.9% of the world’s workforce (260 million workers) worked from home on a permanent basis. Although some of these workers were old-fashioned ‘teleworkers’, most were not, as the figure includes a wide range of occupations including industrial outworkers (e.g. embroidery stitchers, beedi rollers), artisans, self-employed business owners and freelancers, in addition to employees.

Employees accounted for one out of five home-based workers worldwide, but this number reaches one out of two in high-income countries. Globally, among employees, 2.9% were working exclusively or mainly from their home before the COVID-19 pandemic. But close to 18% of workers work in occupations and live in countries with the infrastructure that would allow them to effectively perform their work from home (ILO 2020).

This estimate matches others for the UK, namely 18% of jobs in the UK–5.9 million in total–are ‘anywhere’ jobs. Looking at the occupational breakdown, anywhere jobs are predominantly in professional (36%), technical (30%), and administrative (24%) occupations. Of all anywhere jobs, 1.7 million (28%) are in the finance, research, and real-estate sectors, and 1.1 million (18%) are in transport and communication.

| Here are the numbers on job postings that were geared towards remote work: Industry |

% Remote (Sept 2020) | % Remote (Sept 2021) | Change |

| Software & IT Services | 12.5% | 30.0% | 17.5 |

| Media & Communications | 12.5% | 21.3% | 8.8 |

| Wellness & Fitness | 3.3% | 21.2% | 17.9 |

| Healthcare | 3.2% | 14.4% | 11.2 |

| Nonprofit | 4.6% | 14.1% | 9.5 |

| Hardware & Networking | 2.2% | 12.9% | 10.7 |

| Corporate Services | 5.2% | 9.5% | 4.3 |

| Education | 9.4% | 8.8% | -0.6 |

| Entertainment | 3.0% | 7.7% | 4.7 |

| Finance | 1.8% | 6.5% | 4.7 |

| Consumer Goods | 2.2% | 6.0% | 3.8 |

| Recreation & Travel | 0.2% | 3.7% | 3.5 |

| Manufacturing | 1.4% | 3.0% | 1.6 |

| Energy & Mining | 1.0% | 2.7% | 1.7 |

| Retail | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.2 |

But the move to remote working or four-day week is still being fought against by most bosses. Why? For two reasons. The usual one offered is that when staff are in the office, they are ‘more productive’. It’s harder to collaborate and be creative with colleagues over endless video calls. That’s not the view of many workers, however, who say they get much more done at home without gossiping and other office distractions. In 2015, a study of 16,000 call centre staff found that those who worked from home (WFH) were 13% more efficient than their office-based colleagues. The WFH team were more productive as they took fewer breaks, were sick less often and put in more calls an hour as they didn’t get distracted by tea breaks and water-cooler moments.

The spatial freedom to work outside the office, supercharged by the pandemic, has increased the temporal freedom to work at any time. “Asynchronous work” is the new buzzword in HR and management circles. This has advantages: it avoids the unpleasant synchrony of everyone cramming on to trains every morning and evening and allows people to fit work around other priorities or responsibilities.

But there are downsides too. A study published in 2017 of workers in 15 countries found that the impact of remote work on work-life balance was “highly ambiguous”: workers reported more time with their families, but also an increase in working hours and blurred boundaries between paid work and personal life.

There are also concerns about the potential mental health impacts of working from home. Research by management consultancy firm McKinsey found that working from home had actually increased “burnout” rates among all employees as they struggled to juggle their careers and family lives, and this was particularly the case for women. The survey of 65,000 employees found that the gap between male and female burnout rates nearly doubled, with 42% of women reporting burnout compared to a third of men.

But the real reason for opposition by employers is not just lower productivity but that management starts to lose control over its employees, both in terms of time and in dictating activity. The oppressive boss-employee relationship begins to weaken. And of course, there is the question of money. The London law firm Stephenson Harwood is allowing its staff to work from home 100% of the time–but only if they take a 20% pay cut. “Like so many firms, we see value in being in the office together regularly, while also being able to offer our people flexibility,” a spokesperson said. On the popular law industry website RollOnFriday, one Stephenson Harwood lawyer said the “100home80pay” policy was “a total gamechanger”. “I get to live in Bath and work for a City firm”, earning more than at their former regional firm “even after the 20% discount”.

These objections by the bosses to remote working and a shorter working week are now to be tested in a new pilot scheme. More than 3,000 workers at 60 companies across Britain will trial a four-day working week, in what is thought to be the biggest pilot scheme to take place anywhere in the world. Joe O’Connor, the chief executive of 4 Day Week Global, said there was no way to “turn the clock back” to the pre-pandemic world. “Increasingly, managers and executives are embracing a new model of work which focuses on quality of outputs, not quantity of hours,” he said. “Workers have emerged from the pandemic with different expectations around what constitutes a healthy life-work balance.”

That sounds great for the professional classes in finance, law and technology. Overall, 48% (2.8 million) of those in anywhere jobs have a degree. Indeed, 20% of people educated to degree level or higher in the UK are working in an anywhere job. But the majority of workers are not needed in such anywhere jobs. Most work in jobs that pay poorly and require full-time activity away from the hone. In the UK, just 6% of people earning £15,000 or less are working from home every day, and only 8% have hybrid working privileges.

The British Trades Union Congress (TUC) has warned that working from home risks creating a “new class divide” as frontline workers in supermarkets and hospitals, mechanics and other customer-centric jobs do not have the option to work from home. Frances O’Grady, the TUC general secretary, says: “Everyone should have access to flexible working. But while home working has grown, people in jobs that can’t be done from home have been left behind. They deserve access to flexible working, too. And they need new rights to options like flexitime, predictable shifts and job shares.”

The reality is that for most workers the decline of the “9 to 5” has been under way for decades. In 2010-11, 20 per cent of employees in the U.S. worked more than half their hours outside the standard hours of 6am to 6pm or on weekends. A vast survey of workers across the EU in 2015 found about half worked at least one Saturday a month, almost a third worked at least one Sunday, and roughly a fifth worked at night. And this is mostly at the workplace not at the home.

One common shift pattern for production and warehouse workers today is to work four 12-hour days, have four days off, then work four nights, then have another four days off. Another is to work eight-hour shifts on rotation. As one current UK job advert for a warehouse job explains: “The hours of work are: 6am to 2pm, 2pm to 10pm, 10pm to 6am. You will work one week on one shift and then rotate, therefore flexibility to cover all shifts is required.” No home working there.

Factories and warehouses aren’t the only workplaces that run around the clock. Shift work is common for doctors, nurses, carers, drivers and security guards, among others. It appears to be on the rise. In 2015, 21 per cent of workers in the EU reported doing shift work, up from 17 per cent a decade earlier. While shift work suits some people, the evidence suggests it damages their health, especially if they rotate between days and nights. Twelve-hour shifts, rotating shifts and unpredictable schedules are associated with higher risk of mental illness, cardiovascular problems and gastrointestinal problems.

Shift work can also harm family life. “Divorce is pretty bad. We see a lot of divorce, just due to the fact that families, especially young couples, you’re away from your family [for] 12 hours, and then when you go home after a 12-hour shift, you just want to sleep,” one manager in a U.S. manufacturing plant told academics studying the impact of shift work. A worker in the same study said: “It changes our time with our family. It changes our time with our social life and church and community groups. All those things that you would like to be involved with.”

Remote working may be here to stay; and many employers may agree to a four-day week (but almost certainly only if ‘productivity’ rises enough to justify it and probably with a pay cut). But the daily (and nightly) drudge on barely acceptable rates of pay will continue for most workers.

The future of work–part 2 will cover how working hours have been getting longer leading to serious damage to the health of millions.