My 8th grade classroom was a standard rectangle with two doors, 36 desks in rigid rows, and fluorescent lights hanging from a ceiling of acoustic tiles. I was easily bored. The only thing I found interesting was a small bookshelf filled with unassigned books that we were invited to borrow.

That was where I discovered a book with a burning book on its cover. It was Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, and I took it home. The next day a neighbor, visiting my parents, saw me reading and told me that my book had been banned. I had no idea what he meant, so I asked. He responded vaguely that he heard it was a “bad book.”

At that age I rarely took adults seriously but I thought he might be joking because the book was about a future where books were outlawed and “firemen” burned them. I asked if he had read the book and he mumbled “no.” So, I concluded he wasn’t joking but was probably unsure of what a bad book was.

Sometime later I heard that Fahrenheit 451 had not actually been banned, but that some people objected to it being read in schools. That turns out to be a common source of confusion. As a result of the First Amendment, the U.S. government can’t exactly ban books, so it has been left to the efforts of individuals, small groups, or specific school boards to encourage local bans. A “banned” book is usually a very local matter, and Fahrenheit 451 had been, and still is, challenged in a number of schools and libraries throughout the country.

The first book banned in North America would have made a perfect model for a Monty Python film. The book, titled New Canaan, was written by Thomas Morton in 1637. It was a satire of the Puritans and William Bradford, the governor of Plymouth Colony, who was accused in the text of being the “Lord of Misrule.”

Since the 1960s attempts to limit what can be read or studied has become increasingly common. At the beginning of that decade, Beatrice Levin, a teacher at Edison Prep in Tulsa, Oklahoma was nearly fired for assigning J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye to an 11th grade English class. The parents who challenged that book cited “profanity” as a reason for the book to be removed.

I heard of that controversy in my own high school English class and immediately found and read The Catcher in the Rye hoping for something exciting, but I was profoundly disappointed. The only profanity I remember was the overuse of the word “bastard.”

Ironically, one of the most frequently banned books in this country is George Orwell’s 1984. Again, those objecting to the book cite “profanity,” but I would bet their real objection is that the book hits too close to home. In the text, written in 1948, Orwell describes a recognizable perversion of language (Doublethink and Newspeak), targeted use of propaganda, and the sophisticated use of technology for surveillance.

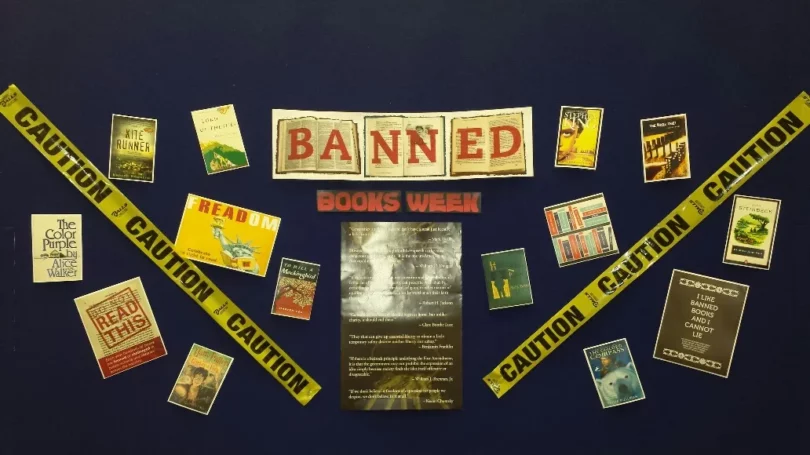

Conveniently, the American Library Association publishes lists of challenged and banned books both by year and by decade. In the ALA list covering the 1990s most of the challenged books are what I expected: books like Huckleberry Finn, The Catcher in the Rye and The Color Purple because of profanity and sexual situations. The list for the decade 2000 to 2009 is quite similar, but the list for 2010 to 2019 shows a growing emphasis on books meant for kids with an intense focus on some of the most sensitive issues kids have to deal with.

According to PEN America, more books are now being banned in more school districts than in previous years. In a report that covers July 2021 to March 2022, PEN has also discovered an increased role of organized efforts to drive many of the bans. The report concludes that from July 2021 to June 2022, there were 2,532 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,648 book titles written by 1,261 different authors.

The majority of challenges to books in schools and libraries are no longer coming from reactive parents. As the PEN report noted, they are organized efforts that “reflect the work of a growing number of advocacy organizations that have made demanding censorship of certain books and ideas in schools part of their mission.” There is no longer a generalized objection to profanity. These attacks are narrowly focused on LGBTQIA+ issues, sexual identity issues, and the roots of racial tension.

One has to wonder why. The issues are undeniably important. They affect virtually everyone in one way or another, and they are increasingly written about for that reason. Attacks on these books appear to be attempts to pretend that the issues are not important, that they don’t actually impact young people, or that they are manufactured by some liberal conspiracy.

Whatever their justification, reactionary politicians clearly want to restrict how public schools address racial history, sexual orientation and gender identity. There is a vicious attempt to delegitimize all sexual identity issues, purposely confusing them with loaded terms like pedophilia, grooming and child abuse.

According to Adrienne Westenfeld, books and fiction editor at Esquire Magazine, dealing with the fact of racial tension has suffered the same fate. The often-misused term “critical race theory,” usually purposely left undefined, has been weaponized to demonize any curriculum that highlights issues of racism, history or privilege. Senator Ted Cruz has been a prominent proponent of this strategy.

In an article published in The New Yorker, Benjamin Wallace-Wells characterizes efforts to attack anything dealing with racial tension as an attempt to “cleave off students from any feeling of historical responsibility—as if, with each generation, America were re-created, blameless and anew.”

In the Senate confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson, Sen. Cruz began criticizing the books available to kids at Georgetown Day School, where Judge Jackson sits on the board of trustees. He loudly proclaimed to viewers (and to Judge Jackson) that, “If you look at the Georgetown Day School’s curriculum, it is filled and overflowing with critical race theory…”

Holding a copy of Antiracist Baby by Dr. Ibrim X. Kendi, he asks the judge: “Do you think babies… are racist?” Jackson sighed and calmly explained to Senator Cruz that “Critical race theory, as an academic theory, is taught in law schools.”

Of course, Ted Cruz is not alone. And attempts to prevent dealing with these issues are not restricted to challenging books. Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, has signed the “Parental Rights in Education bill” also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law, which prohibits classroom instruction and discussion of gender identity through third grade. Other states have similar bills pending.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has attempted to criminalize gender-affirming pediatric care and asked the state’s education agency to investigate “the availability of pornography” in public schools. DeSantis also signed a bill nicknamed the “Stop WOKE Act,” which aims to regulate how schools and businesses address race and gender.

It does not matter if the target is LGBTQIA+ issues, sexual identity issues, or whatever is considered critical race theory. The claim is that censorship is necessary. Kids need to be protected from any instruction, any reading, any discussion of sexuality, or sexual identity, or slavery, or the history of race in this country in order to isolate them from reality. That is the updated justification for banning books and, even more repellent, for banning discussion. The claim that kids are threatened by thinking about such issues is an attempt to intimidate parents and to make voters feel that if they don’t agree with censorship, if they don’t agree with what has been billed as “patriotic education,” they will lose control of the future. Reactionary censorship is simply one tool in the struggle to control institutions that define American democracy, in this case public education in both schools and libraries.