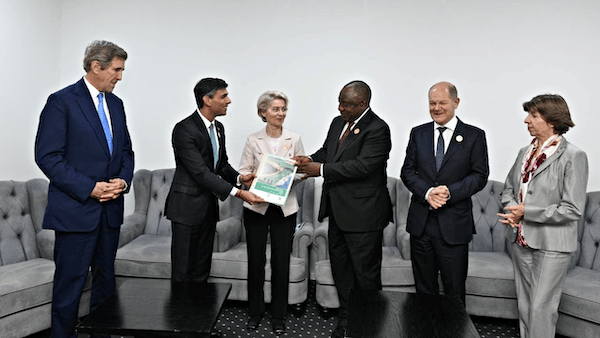

During the World Leaders Summit at COP27, South African president Cyril Ramaphosa launched the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP).

The plan is the product of a process that began a year ago at COP26, when the U.S., the UK, France, Germany, and the European Union, collectively called the International Partners Group (IPG), announced the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) with South Africa.

The JETP set a lofty goal–“to accelerate the decarbonization of South Africa’s economy, with a focus on the electricity system” to help it reduce harmful emissions as set out in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement.

However, progressive forces have warned that the plan will have a disastrous impact on working class communities, especially those dependent on the coal sector for their livelihood, while driving a massive privatization of South Africa’s energy sector.

Presenting the Investment Plan on November 7, President Ramaphosa stated that South Africa would need $98 billion over the next five years to enable a just transition. The plan identified three priority sectors for investments: electricity, green hydrogen, and new energy vehicles. The Plan was endorsed by South Africa’s Cabinet on October 19.

For its first phase, the IPG is ‘mobilizing’ $8.5 billion including “grants, concessional loans, and investments and risk sharing instruments” from both public and commercial lenders. According to an official statement, the funding will be geared towards coal plant decommissioning, funding alternative employment in coal mining areas, investments towards renewable energy, and new sectors of the green economy.

$2.6 billion will be allocated through the Climate Investment Funds Accelerating Coal Transition Investment Plan, $1 billion each from the U.S., EU, France, and Germany, and $1.8 billion from the UK.

“A ‘Just’ approach underpins the Plan,” a joint statement declared,

aiming to ensure that those most directly affected by a transition from coal—workers and communities including women and girls—are not left behind.

How is the JETP actually approaching just transition in South Africa–by pushing a country where over 55% of people are already living in poverty and 46% are unemployed further into debt? Only around 4% of the IPG funding package is in the form of grants. 81% is loans.

Not only that, nearly 90% of the financing is geared solely towards infrastructure. Skill development and economic diversification and innovation, which would undergird any commitment to justice in the JET-IP, have been allocated only 0.1% and 0.3% of the financing respectively.

Privatization and energy poverty in South Africa

On paper, nearly 85% of South Africa’s population has access to electricity. However, rolling blackouts or loadshedding and high prices have effectively placed it out of reach for millions in the country.

Instead of developing and properly managing the state-owned, and coal-power dependent, utility company ESKOM, the South African government has chosen the path of austerity and privatization.

“By virtue of it being a state-owned entity, ESKOM can drive a developmental agenda, which means that by its very nature, it should not be making profit, rather it should be creating space for the provision of affordable and reliable electricity. If it was well-run, it would be able to do that,” the national spokesperson for the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), Phakamile Hlubi-Majola, told Peoples Dispatch.

ESKOM’s challenges have everything to do with poor governance and the African National Congress’ own policies of dumping our state owned entities (SOEs).

The Institute of Economic Justice points out further that the JET-IP deal relies heavily on using funds to ‘de-risk’ private investment. Moreover, financing is “tied to the expansion of private-sector energy generation, through lock-ins and demand agreements, which will likely raise the cost of energy provision thereby limiting access and exacerbating energy poverty.”

It added that the plan ignored “energy affordability concerns,” focusing instead on access to the grid as a means to reduce energy poverty. The JET-IP emphasizes “cost-reflective tariffs,” which the institute argues will lead to continued high electricity prices and restrict cross-subsidization for the poor.

As Hlubi-Majola stated,

There is no privately-owned company that will care about providing affordable energy for all, for the poor and the indigent. That is not the goal… their goal is to drive profit.

“Despite the public perception that the accelerated drive toward renewable energy is fueled by climate change,” argues engineer and researcher Brian Kamanzi,

the reality is that it is primarily driven by imperatives to implement private sector reform in the power generation sector. This is done by leveraging the advances in renewable energy systems.

This is clearly evidenced by the fact that, as NUMSA points out, the government’s plan says nothing about the future of ESKOM— “ESKOM’s role seemingly is simply to enable the private sector to access the grid, but it will not have any direct role in providing renewable energy to the population.”

A major share of new investment will be private and in the form of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Program (REIPPP). NUMSA had tried to block its rollout in 2018, arguing that its introduction would mean that coal-fired power stations would be shut down to make way for privately-owned renewable energy companies.

Even though the government has committed to shutting down power stations, Hlubi-Majola stated that affected communities had not been meaningfully engaged–“This is a total violation of the principles of a just energy transition as defined by the International Labor Organization which stipulates that communities and workers must be the ones to not only drive the consultation process, but also that they must be the ones to define the resulting plan because that plan must benefit them directly.”

What we have seen instead is the government embarking on a box-ticking exercise after already beginning the process of shutting down power stations.

An estimated 124,000 jobs would be lost by 2030 in an escalated decommissioning of ESKOM. 8,000 people in Mpumalanga in the coal belt would directly lose their jobs, not to mention families and communities that would be impacted in a myriad other ways. There is no social plan in place for them. According to NUMSA, 12 out of ESKOM’s 15 coal-fired power stations are located in the region.

ESKOM has already started leasing the land around its power stations in Mpumalanga to renewable energy companies. It employs approximately 30,000 people across the country.

Looking at the REIPPP more specifically, Hlubi-Majola added,

Earlier this year, when ESKOM was making an application to the national energy regulator, NERSA, to increase its tariffs, it stated in its submissions that a big part of the increases was a result of the cost of the REIPPs. These REIPPs are a part of ESKOM’s cost burden.

ESKOM is spending a large portion of the money it has on exorbitant primary energy costs which, for over the last 10 years have increased by 17% year by year.The REIPPs are a part of these primary energy costs which are choking ESKOM and choking the consumer.

“You are not even future-proofing your own state-owned entity to play an important role in this climate change scenario…[I]t is a mistake for the South African government to hand over this process of transitioning from coal to renewable energy [from ESKOM] to the private sector and hoping that the private sector will miraculously deliver on a developmental agenda,” Hlubi-Majola had earlier emphasized in an interview with Breakthrough News.

“By handing over ESKOM in this way, basically destroying its future and enabling and allowing the private sector to play a greater role in energy generation, the government is betraying the working class. They are guaranteeing that South Africans remain poor, that the country’s status as the most unequal in the world continues for generations to come,” she told Peoples Dispatch.

We have a duty to ensure that our SOEs play a direct role in empowering the working class and the masses. Unfortunately, the South African government has been reading from the playbook of the World Bank and other international financial institutions who have been driving an agenda of neoliberalism and privatization

A just transition for the people, not profit

Even as the global South is already bearing the historically unjust burden of the climate crisis, industrialized countries of the North seem to be moving backwards, re-opening coal plants to secure their own energy supplies while touting the importance of a just climate transition on the international level.

“You cannot industrialize your economy based on renewable energy alone because it is an intermittent form of energy, you need a base load supply that is either coal or nuclear.” Hlubi-Majola explained.

Even as Germany is reopening its coal plants, South Africa is closing them down. Germany is not the one facing frequent blackouts.

Load shedding has cost South Africa’s economy over $4 billion rand (US$2.3 billion) in 2022 alone.This has a direct impact on our economic outlook. If we are serious about job creation, about building the economy and absorbing the unemployed, we must industrialize. Unfortunately, the renewable energy plants are not labor-intensive.

Despite the fact that all of Africa has contributed a miniscule portion of global carbon emissions, Hlubi-Majola asked, why are countries on the continent “racing to implement a transition which we know objectively is very disruptive and will result in more poverty and unemployment. Why are we doing more than those who are actually responsible for this climate crisis?” Especially when there is no plan in place to mitigate the effects of the JETP deal on local communities.

The importance of a just transition is not lost on the global South, where communities at the frontlines have been fighting for survival for decades. The question is what does a truly just transition look like?

For years, NUMSA has been calling for a ‘socially-owned renewable energy sector’.

“When you look at the JET-IP, there is no ownership component for the benefit of workers or communities,” Hlubi-Majola noted importantly,

they are not talking about renewable energy companies that are owned through cooperatives.

“For us, a just transition would have been one that allowed workers and communities of Mpumalanga, who stand to lose the most from this deal, ownership of renewable energy companies. The technology that is being used should be owned by South Africa… How do we stand to benefit from this deal when there is going to be so much disruption and displacement for ordinary workers and their families?” she asked.

The only people who stand to benefit are a minority of the elite. Among the biggest beneficiaries is Patrice Mostepe, who is related to President Ramaphosa through marriage, and whose firm won 12 out the 25 renewable energy plans.

A just transition, Hlubi-Majola stressed, would have been one where “ESKOM (an SOE) would control at least 70% of the renewable energy space in this country. In doing so, you would have safeguarded the jobs of the thousands of workers at ESKOM, you would also be transforming it from the coal-guzzling, polluting entity that it is to one that is contributing to tackling climate change directly.”

They must stop perverting the term just transition. There is nothing just about this current process.