17 years ago, the residents of 12 informal settlements in the city of Durban came together and formed Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM), or ‘shack dwellers’ in Zulu. The movement emerged at a time of widespread mobilizations against the ruling African National Congress’ failure to fulfill its promises to provide services and housing for the poor in post-apartheid South Africa.

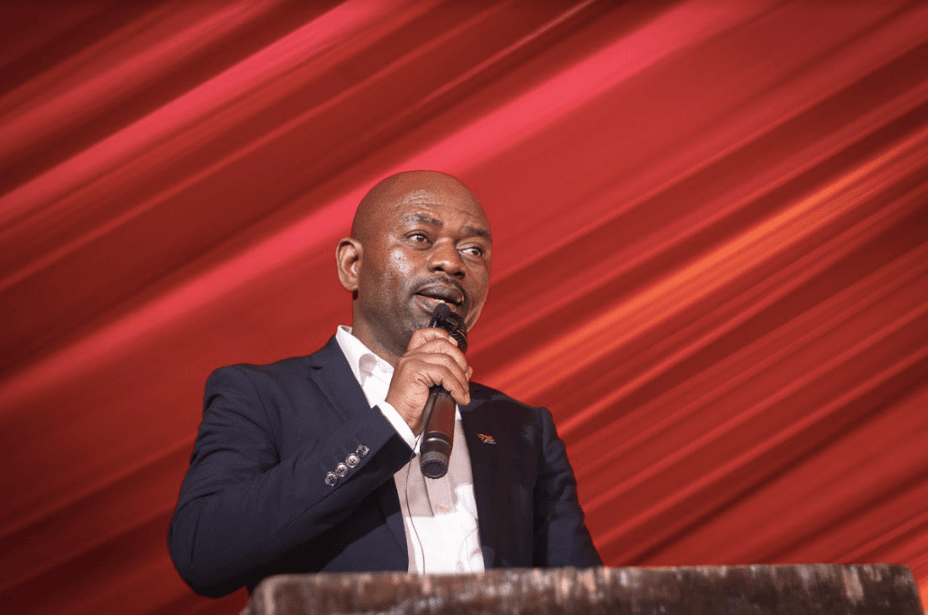

Abahlali baseMjondolo President S’bu Zikode speaks at the funeral of slain leader Lindokuhle Mnguni. (Photo by Siyabonga Mbhele)

“What do we want?” AbM’s founding member and president, then 30 year-old S’bu Zikode had asked in 2005,

The basics. Water, electricity, sanitation, land, and housing.

Over the following years, AbM grew into a militant collective with more than 100,000 members, fighting for dignity and land for the urban poor in the face of deadly repression by state forces.

The movement’s struggle was the subject of a photo exhibition which opened at The Forge in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, on November 17, titled “Socialism or Death,” featuring the work of two photojournalists, Nomfundo Xolo and Siyabonga Mbhele.

The event’s name was a reference to a conversation between the leaders of the AbM’s eKhenana Commune, Ayanda Ngila and Lindokuhle Mnguni, when they had been imprisoned. “We used to talk a lot about death because we knew someday luck won’t be on our side. They will kill us. He [Ngila] even said, Socialism or Death,” Mnguni would explain later.

Because we want it, no matter what it takes. Even if it means death, because we can’t really continue living in these inhumane conditions.

February 9, 2021. Best friends reunited. Lindokuhle Mnguni (left) and Ayanda Ngila (right) were each other’s support system. After being rejected by the City and pushed out of their rural homes due to poverty, they finally found a place of belonging. Both were leaders in the Commune who believed in self-sustenance and communism. (Photo and caption by Nomfundo Xolo)

29-year-old Ayanda Ngila was shot and killed on March 8, 2022, by four gunmen allegedly led by Khaya Ngubane, the son of a local leader of the ruling ANC.

March 8, 2021. The body of Ayanda Ngila wrapped in a body bag while forensic police document the scene. Ngila was gunned down in broad daylight by known suspects who opened fire on eKhenana residents who were on their way back from fixing a disconnected water pipe. (Photo and caption by Nomfundo Xolo)

Just months later, Lindokuhle Mnguni was killed by two gunmen at his home in the early hours of August 20. He was 28 years old.

Lindokuhle Mnguni’s home. Gunmen broke the shack’s window using a spade, kicked down his door, and opened fire on him and his partner. (Photo by Siyabonga Mbhele)

“I received a call at around 8am that comrade Lindo [Mnguni] had been shot, at first I could not believe it…,” Siyabonga Mbhele told Peoples Dispatch.

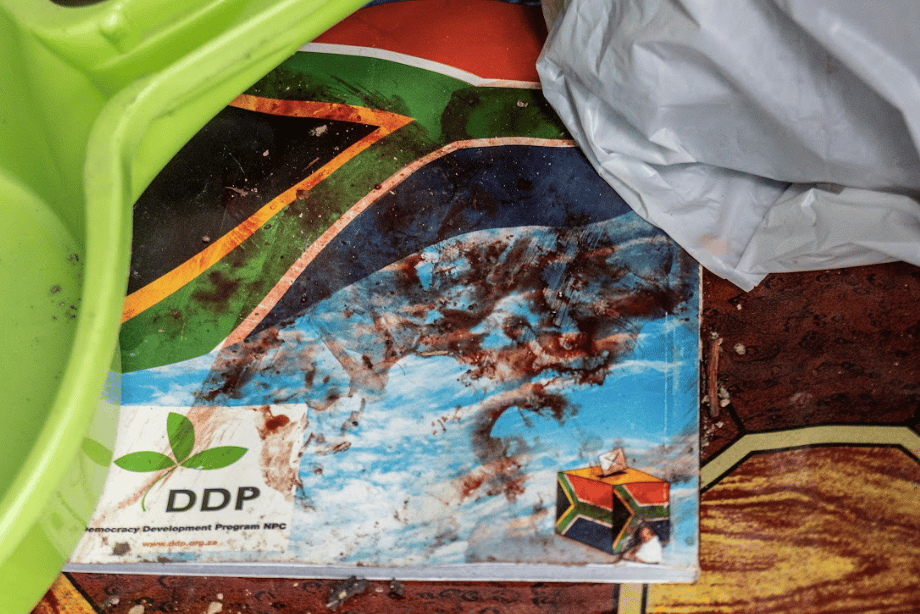

When I reached his house and went inside, I found a book with the words ‘Democracy’ and ‘Development’ under a picture of the South African flag. The flag was covered in Lindo’s blood.

A booklet titled “Democracy Development Program NPC covered in the blood of slain leader Lindokuhle Mnguni inside his home. (Photo by Siyabonga Mbhele)

“This picture is the closest to my heart because Lindo was fighting for democracy, not the so-called democracy that we have today that only works for the rich and not the poor. This picture shows that the South African flag is covered in the blood of the poor. We have lost so many comrades since 2005. This picture portrays that while it may be a beautiful flag, it symbolizes nothing for the poor of South Africa,” Mbhele added.

A scene from the burial ceremony of Lindokuhle Mnguni. (Photo by Siyabonga Mbhele)

Mnguni was laid to rest on a plot of land in a rural area in the KwaZulu Natal province, which had been bought along with his mother. “They have not built anything on that land because materials are very expensive, especially for the poor,” Mbhele said,

But Mnguni became the first person in his household to occupy that land. His house in a sense, his grave, became the first thing to be built on that land.

Mnguni and Ngila are among four AbM leaders killed in 2022, so far. As the eKhenana Commune was still reeling from the assassination of Ngila, 40-year-old Nokuthula Mabaso was fatally shot on May 5, a day before she was set to appear at a court in Durban to oppose the bail of Khaya Ngubane. Ngubane’s father and his uncle were arrested for Mabaso’s murder and are awaiting trial.

These killings have punctuated the near-daily violence and intimidation faced by Abahlali baseMjondolo. Its members have been repeatedly arrested and imprisoned on trumped-up charges, only to be released months later due to a complete lack of evidence.

In a statement on November 27, the movement announced that three members, Maphiwe Gasela, Lando Tshazi, and Siniko Miya, had been arrested yet again, in relation to a murder committed in 2020. The matter of their bail hearing has been adjourned to December 13.

While documenting the horrific attacks on AbM in their photo exhibition, Nomfundo Xolo and Siyabonga Mbhele also drew close attention to what the movement, and its slain leaders, have striven to build.

“While the desire and urgency to address land matters is enshrined on paper, land deprivation in South Africa mimics an unequal and unjust reality which indicates a legacy of the extreme structural oppression from Apartheid,” Xolo has argued.

“The main things that the apartheid regime insisted on was segregation, to ensure that Black people were excluded from the economy. You can sense it even now in the city, it is as if you are not supposed to be here. People have been cast aside in the shack settlements,” she said in an interview with Peoples Dispatch.

In rural areas, people are deprived of what they should be able to get from the land and as a result, young people are moving to the city. However, once you are in the city, you cannot live off the land, you cannot plant anything, you cannot stay anywhere. You are fighting for your place in the economy.

Under these conditions, the AbM offers hope. Xolo added,

Through a movement, people are fighting, they are resisting… I want to make sure that they are not forgotten. You see them being evicted, their houses being burned, or their children being killed, yet they are back to the struggle the next day. They have the will.

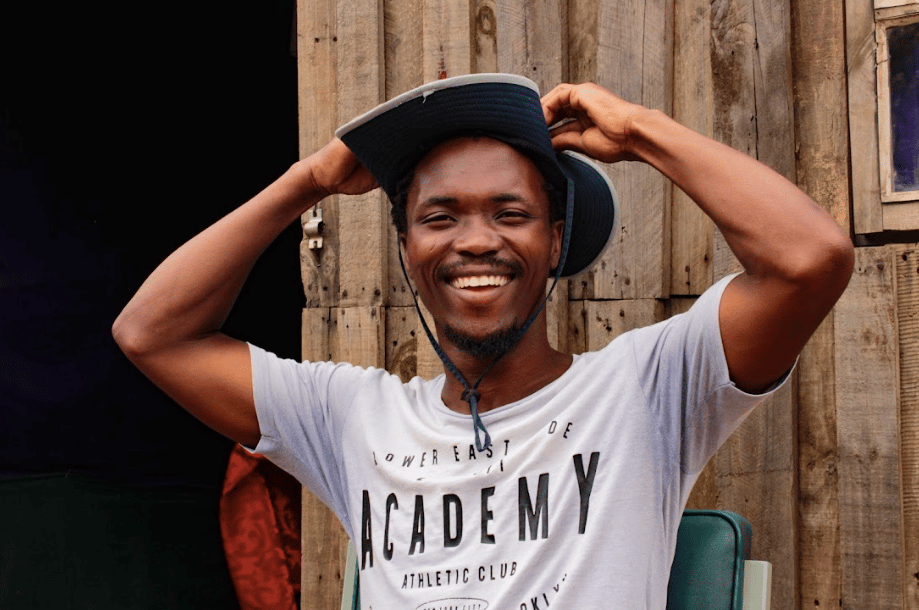

February 9, 2021. Chairperson of eKhenana Commune, Lindokuhle Mnguni dedicated his efforts into creating the land of milk and honey. He believed in working the soil: “It is not enough to only work the soil, community members need to also understand and embrace that the soil is us, it feeds us and defines us. If we can feed ourselves, we have begun unchaining ourselves from the oppressor.” (Caption and Photo by Nomfundo Xolo)

In 2018, AbM occupied vacant land in Cato Manor and set up the eKhenana settlement. It was organized as a commune, with a collectively-managed kitchen, vegetable garden, poultry farm, and a tuck shop. In late 2019, the Frantz Fanon school for political education was established.

AbM members gather outside the Frantz Fanon school for political education established at the eKhenana Commune, after the assassination of Lindokuhle Mnguni. (Photo by Siyabonga Mbhele)

The residents of eKhenana have built community toilets and set up systems for sanitation and electricity supply by themselves, without the permission or patronage of the state.

Since 2009, 24 members of AbM have been killed, out of which eight were leaders associated with the eKhenana Commune. Several have been arrested on charges ranging from public violence to murder. The commune itself has been violently and illegally evicted at least 30 times. Its members have been attacked by the metro police, armed private security, and the Anti-Land Invasion Unit under the local ANC-ruled municipality.

October 1, 2021. Nokuthula Mabaso pioneered the communal projects and dedicated her life towards feminism at the movement, Abahlali baseMjondolo. She was instrumental in developing the commune’s food sovereignty projects, which included a poultry farm. This allowed the residents to generate enough revenue to sustain their community. On this day, she had just given a welcome speech after detained activists, Ayanda Ngila, Siniko Miya, Lindokuhle Mnguni and Landu Tshazi were finally free. (Caption and Photo by Nomfundo Xolo)

For both Xolo and Mbhele, a key emphasis of their work was to challenge the dominant portrayals of shack-dwellers as “illegal occupants” by the government and in media coverage. This criminalization is explicit in the terms used by state forces, as Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI) researcher Thato Masiangoako highlights, calling informal settlements ‘land invasions’.

It was important to portray AbM members as human beings, to have readers resonate with them, and to be enraged at their circumstances, Xolo explained. She has been documenting the struggle at eKhenana since 2018, since the very first evictions. “The Calvin Family Security [a private security company contracted by the eThekwini municipality became synonymous with eKhenana. There were evictions taking place almost every day, sometimes twice a day. And these evictions came with arson, they would burn people’s houses down,” she says.

“Even the security agency and the municipality would have assumed that after 10 evictions the people of the settlement would get tired.” Yet the members of eKhenana continued to rebuild.

Amid this violence, Xolo added, “A question that then came up was why couldn’t these people go home? Was there somewhere they could go back to?” However, there was a realization that “These people are displaced, they do not have an option B, not even to return to the rural areas. To survive as a young Black person in rural areas, you need access to resources… access which is not there.”

“A lot of the people in eKhenana are young… they understand the value of land, that it can feed you and others. They are much more aware of the goal, to ensure that future generations are in a much better place… You see communism in its reality, in an urban space, in eKhenana…and that is seen as a threat.”

“The initial plans behind the commune were very concrete. I remember talking to Nokuthula and spoke about how, especially if you have experienced poverty, you have a vision of where you want to see your children, to not have them have to struggle for informal work,” Xolo said.

After Nokuthula Mabaso was killed, work on eKhenana’s communal projects, including the tuck shop, had been halted. However, in July, the commune’s residents decided to resume working on the vegetable garden and poultry farm. There is a clear understanding, Xolo said, that “when you really try to break out of the capitalist system they will make sure to chop off your roots immediately”.

Despite this, the garden and the farm have sustained eKhenana, pulling them through the court cases and the arrests, “which makes you think, that if all this is possible through just two small projects, what would it look like if the other initial plans could survive, we could have an entire economy in the settlement.”

“Even in the midst of all this chaos, eKhenana offers hope, they are still struggling to find that land of milk and honey, and it is hard, yet they keep going. They are still getting arrested, but one leader emerges after the other, it does not stop,” she added

“The fate is death and that cannot be accepted,” Xolo stressed. “We cannot get used to this, for people to be killed just for wanting a decent life. My purpose with this exhibition was to make sure that people do not forget their faces, Mabaso, Ngila and Mnguni are an example of what it means to be a young African today, where you have to struggle just for land and housing.”

“They were people with beautiful ambitions for their futures and for the land. We cannot turn away from these assassinations, history has repeated itself again when people have paid by blood… But the picture in eKhenana will always be one of encouragement and hope”

All images shared courtesy of Nomfundo Xolo and Siyabonga Mbhele.