The United States is an employment “at-will” country. That means, absent a union contract, a boss can fire a worker for almost any, or even no reason, and without advance notice. Well—with the exception of Montana. As the state’s employment division explains:

Montana is not an ‘at-will’ state. . . generally, once an employee has completed the established probationary period, the employer needs to have good cause for termination.

While Montana is the exception in the United States, the United States is the exception among developed capitalist economies. In those other countries, most workers can only be dismissed for “just cause,” with just cause statutorily or judicially defined. For example, German workers employed for more than six months by a company with more than ten workers cannot simply be dismissed. The company must have a valid business or personal conduct reason. Moreover, the company is also required to notify the employee in advance, and in writing, of their termination. Many employees also receive severance pay proportional to their length of employment.

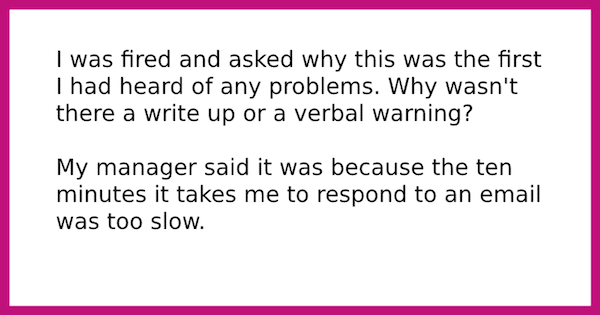

So, how big a deal is employment at-will in the United States? According to the results of a recent survey by the National Employment Law Project (NELP), carried out by YouGov, more than two out of three workers who have been discharged received no reason or an unfair reason for their termination. Almost three out of four received no warning before discharge.

Employment at-will is a judge-imposed doctrine. There is no federal law imposing employment at-will on workplaces. We need to shine a bring light on the destructive consequences of this doctrine and mount a campaign to replace it with a just cause standard.

The origins of at-will employment

The U.S. embrace of at-will employment has its origins in the work of Horace Gay Wood, a New York-based legal writer, and his 1877 treatise titled Master and Servant. American law originally followed early English law on contracts. English courts, as early as the 17th century, had developed a set of laws to settle disputes over the termination of master-servant contracts covering what were known as “general hirings.”

In broad brush, the courts prohibited servants (which covered a large and variable class of workers) from taking sudden leave from their employment and masters from unexpected discharge of their servants before the end of a term, which was often defined as a year or a relevant season of work. Wood argued against this tradition, writing:

[T]he rule is inflexible, that a general or indefinite hiring is prima facie a hiring at will, and if the servant seeks to make it out a yearly hiring, the burden is upon him to establish it by proof…. It is competent for either party to show what the mutual understanding of the parties was in reference to the matter; but unless their understanding was mutual that the service was to extend for a certain fixed and definite period, it is an indefinite hiring and is determinable at the will of either party.

And it was not long after the publication of Wood’s treatise that state courts began adopting employment at-will as their ruling doctrine, with most citing Wood’s argument for support. Thus, as a Roosevelt Institute report on at-will employment explains:

The rule that employees can be fired even for bad reasons or no reason at all derives from judge-made “common law” dating to the 1870s. During the early 20th century, the Supreme Court gave constitutional significance to the judge-made doctrine, most famously in a case called Lochner v. New York, but also in cases like Adair v. United States and Coppage v. Kansas. Invoking the employment-at-will rule, the Court repeatedly struck down democratically enacted legislation that protected workers’ rights on the grounds that such legislation violated the “liberty of contract.” Freedom of contract during this period also permitted employers to fire or refuse to hire union supporters, African Americans, immigrants, women, and other disfavored classes of employees. The Lochner-era cases have long since been overturned: No longer does the law hold that legislation protecting workers’ rights to join unions or to earn minimum wages violates the Constitution. Yet employment-at-will remains the rule in nearly all U.S. jurisdictions.

Of course, it should come as no surprise that some corporations would prefer to have it both ways—employment at-will when it comes to termination and restricted freedom of movement when it comes to employee mobility. A case in point: In January 2022, the Wisconsin-based hospital group ThedaCare sought a temporary restraining order to keep seven of its interventional radiology specialty support team from leaving for a competitor health care provider, Ascension. All the members of the team were employed at-will, which meant that they could be discharged at a moment’s notice and were also free to leave in pursuit of other work whenever they wanted.

The seven members had repeatedly expressed their dissatisfaction to ThedaCare’s management, citing chronic underpayment and firings for trivial policy violations. When higher paid openings were posted at Ascension, the workers gave ThedaCare an opportunity to match them. And, when the company refused, the workers applied for the positions and were hired.

ThedaCare argued that the workers were essential to its operation and should be blocked for an extended period from leaving. The judge did grant a temporary restraining order, encouraging the two health care providers to work out a compromise. When none was reached, he ended the order and the workers took their new jobs. This attempt to use the courts to restrain the employment freedom of at-will workers, and the court’s willingness to intervene, even if only for a few days, is a telling example of how business is always seeking to use and shape labor law to its advantage.

The human costs of at-will employment

The NELP survey reveals that abrupt and often unfair terminations are quite common in the United States. Of the 40 percent of U.S. workers that have been fired or let go by employers at some point in their lives, 72 percent report that they were terminated without warning or a chance to improve, and 69 percent report that they were terminated with no reason given or for an unfair reason. Adding insult to injury, only 34 percent of workers who were let go received severance pay.

There are huge costs to this system of at-will employment. The most obvious is the unexpected loss of income and the threat this poses to the wellbeing of workers and their families. As the NELP points out, 41 percent of U.S. workers have only enough savings to cover up to a month of expenses if they lost their jobs today. This is true for 53 percent of Black workers and 39 percent of white workers.

But there is also a less obvious cost that deserves attention. Workers, fearful of losing their jobs, are often reluctant to speak out about their workplace concerns—including health and safety hazards, harassment, discrimination, and wage theft—for fear of termination. In fact, the survey findings include:

- More than one in three workers (35 percent) worked under hazardous or unhealthy conditions to avoid being fired.

- More than one in three (33 percent) accepted less than what was owed to them to avoid being fired.

- Almost half (44 percent) endured verbal abuse or hostility from a manager or supervisor to avoid being disciplined or fired.

- More than half (57 percent) worked unwanted overtime or (59 percent) skipped breaks to avoid being fired.

- Almost two in three (66 percent) worked while sick to avoid being fired.

- Almost half (47 percent) postponed medical care to avoid being fired.

- And almost half (45 percent) neglected important family responsibilities or events to avoid being fired.

It can be different

The court rulings which made employment at-will the law of the land were a response to a changing political and economic landscape, one marked by a growing industrialization and celebration of unregulated markets. There is nothing sacred about the doctrine; it can and should be challenged and changed.

The NELP report highlights a few successful worker-led efforts to replace at-will employment with just cause protections:

In 2019, parking lot workers in Philadelphia won the right to fight unfair firings with a just cause law. In 2020, fast food employees in New York City won similar protections. Workers in unions have continued to fight for just cause in their contracts. In recent years, journalists at publications ranging from the New Yorker to the New York Times’ Wirecutter to BuzzFeed have successfully fought for and won just cause protections in their union contracts. And rideshare drivers won new legislation—first in Seattle and then in Washington statewide—protecting them against unfair terminations.

Of course, much more needs to be done, and the NELP report provides a useful list and discussion of key protections to be included in any just cause legislation. Some of the most important are:

- The employer must be required to demonstrate a good reason to discharge an employer.

- Certain actions, such as refusing to work under dangerous conditions, should be excluded as grounds for discharge.

- Workers must be given fair notice and an opportunity to address problems.

- Just cause protections should apply to temporary and staffing agency employees.

- Discharged workers should receive severance pay.

- Gig workers should be protected from “deactivation” without just cause.

- There should be strong remedies for violation of the just cause policy.

- There should be effective enforcement vehicles that include opportunities for workers to bring enforcement actions on their own.

Sadly, most workers in the United States know little about labor laws and working conditions in other countries and as a result tend to accept existing arrangements, such as at-will employment, as best practice. We need to shake things up—that should include a concerted effort to educate students from elementary school on up about the realities of work under capitalism and a trade union-led campaign to press elected local, state, and federal representatives to pass legislation that replaces the current at-will employment standard with one that protects worker rights.