A collaboration with the Chris Hani Institute

Long after the decolonisation wave swept across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, two large countries—Brazil and South Africa—remained in the grip of wretched political systems. The military dictatorship in Brazil (1964—1985) and the apartheid regime in South Africa (1948—1994) faced significant challenges from a range of political and social forces. Although many of these struggles are etched into public memory, the role of workers’ resistance is little known outside of unions, as if workers’ struggles were marginal to the story of democratisation.

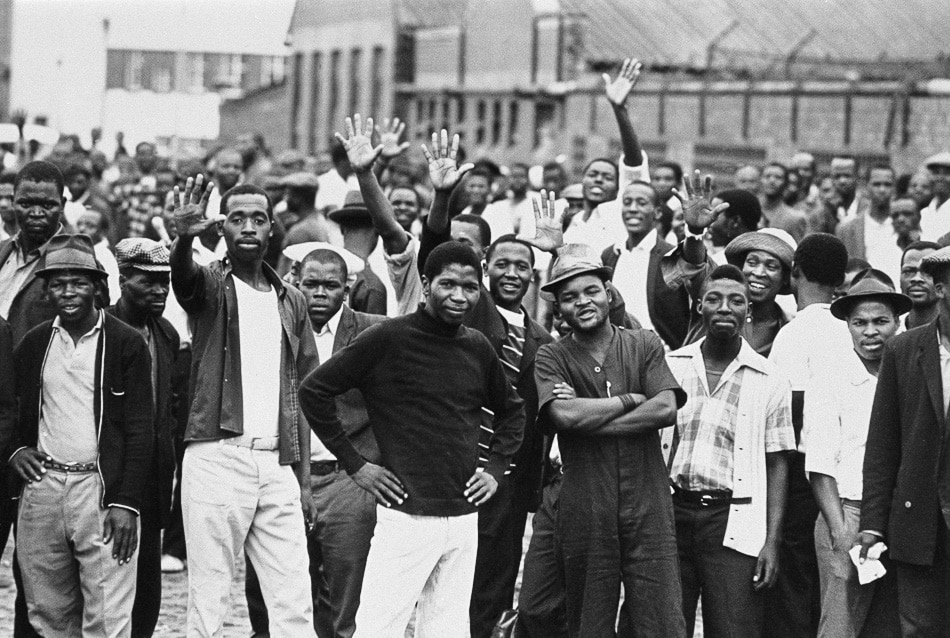

Striking Frame Group workers meet for a report back on negotiations with management in Bolton Hall in 1973.

(Credit: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.)

On the contrary, in both countries, the struggles of workers were central in bringing down odious regimes. In South Africa, the 1973 strikes in the industrial port city of Durban began the process of building a militant trade union movement that would, by the second half of the 1980s, have the apartheid regime reeling from its blows. In Brazil, the 1978—1981 strikes in three industrial cities in greater São Paulo—Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, and São Caetano do Sul—are often said to have marked the beginning of the end of the military dictatorship. The strikes were led by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, then president of the ABC Metalworkers’ Union and the current president of Brazil.

Workers led the way against entrenched forms of domination that not only exploited them, but also oppressed the people as a whole, and the democracies to come were first incubated on the shop floor. This dossier is a contribution to recovering that part of South Africa’s history.

The 1973 Durban strikes were part of a wider political ferment in the city in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when it became a generative site of political experimentation and innovation. Black workers had a long history of organisation and mobilisation in Durban and its surrounding areas. African dockworkers first struck in 1874, and in 1906 many workers, including those labouring in white homes, walked off their jobs to join the rural rebellion against a new poll tax. Led by Bhambatha kaMancinza, the rebellion took the form of guerrilla attacks launched from the sanctuary of the Nkandla forest near Eshowe, a small town to the north of Durban. In 1913, Indian workers on sugar cane plantations, most of them indentured, organised a massive strike. Dockworkers in Durban went on strike again in 1920, and the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union, which was formed on the docks in Cape Town in 1919, became a major force in the city in the late 1920s1 Zulu Phungula, a charismatic worker leader, led another period of confrontation on the Durban docks from the late 1930s.

In 1930, Johannes Nkosi, a dockworker organiser and powerful presence in the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), which was known to workers as abantu ababomvu (‘the red people’), was murdered by the police after he led a public burning of pass books, the documents that the apartheid government required Africans to carry in order to access cities. Between 1949 and 1959, workers on the Durban docks organised another five strikes.

On 12 August 1946, there was a new moment of rupture as African mine workers in and around Johannesburg struck, demanding higher wages. They continued the strike for a week in the face of police terror, which killed nine workers and wounded another 1,248. Although the strike was crushed, it had an enduring impact on struggles for freedom and provoked a shift towards more direct confrontation with the state. The communist-led African Mine Workers’ Union, which had organised the strike, gave birth to the South African Congress of Trade Unions (Sactu), formed in Johannesburg in 1955.

Sactu was aligned with the African National Congress (ANC) and sought to connect labour organising to the struggle for national liberation. The federation played a leading role in the wave of national strikes, which picked up frequency and militancy in the late 1950s. This was also the case in Durban, which, largely as a result of its dockworkers’ tenacity, became a key node of militant trade unionism.

The attempt to exclude Africans from any autonomous presence in urban life was central to the logic of apartheid. Cities were seen as sites of white modernity in which Africans could only be present as strictly subordinated and segregated workers. Pass laws were the key mechanism in the system of oppression that increasingly sought to confine African family life to ethnically delineated rural ‘homelands’ governed in the name of ‘tradition’.

In 1960, the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), a breakaway faction from the ANC, resolved to directly challenge the state on pass laws. On the morning of 21 March 1960, around 20,000 people gathered outside the police station in Sharpeville, a township in today’s Gauteng Province. Tension grew as fighter jets swooped low over the protestors. Barricades were rushed, and the police opened fire on the unarmed crowd, murdering 69 people. As Frantz Fanon wrote, the Sharpeville massacre ‘shook [global] public opinion’.2 On 8 April, the state banned the ANC and the PAC.

Despite its open affiliation with the ANC, Sactu was not banned. It initiated a few strikes the following year, most significantly in Durban, where nurses at King George V Hospital and workers at the Lion Match Company went on strike. But in December 1962, the apartheid government banned 45 officials in Sactu and its affiliate unions, excluding them from public life, and the federation was forced underground. Black trade unionism had largely been smashed.

White supervisors undertake Black labourers’ work in a market in January 1973.

(Credit: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.)

For more than a decade, white power was at ease. The economy grew unevenly but rapidly, and the state appeared impregnable. An authoritarian regime, on and off the shop floor, as well as rising employment and workers’ increased purchasing power, resulted in relative acquiescence. But in 1969, a sudden economic downturn produced retrenchments and an erosion in real wages that put Black workers and their families under growing strain.

New Ideas on Campus

At the same time, new forms of dissent emerged among staff and students on the University of Natal’s Durban campus. Initially this flourishing of political creativity centred around two charismatic men, Steve Biko and Richard Turner, both of whom used their charisma to enable collective deliberation rather than to act as gurus to passive followers.

Biko, who was from King William’s Town (now eQonce) in the Eastern Cape, was educated at Mariannhill Monastery’s St. Francis College outside Pinetown, an industrial area on the western edge of Durban. In 1966, at the age of 22, he returned to Durban to study medicine at the University of Natal’s segregated Black medical school.

Turner was from Cape Town and had completed a doctorate at the Sorbonne in Paris on the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, whose ideas were also important to Biko. He was interested in a range of other thinkers, such as Frantz Fanon, Herbert Marcuse, and Karl Marx, and in recent political experiments in China and Tanzania, as well as Yugoslavia, which he had visited in the 1960s.

Turner proposed a democratic, participatory vision for society rooted in a humanistic Marxism with, he wrote, a specific commitment to ‘popular participation, based on workers’ control’.3 Biko, also a radical humanist, drew on thinkers such as Stokely Carmichael, James Cone, Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, and Kwame Nkrumah.4 He was a sharp critic of the racial paternalism of white liberalism and insisted, against the thinking of some white intellectuals on the left, that discussions of class should not eviscerate the question of race.

Turner, Biko, and their comrades were thinking from Durban amid global political upheaval. The political energies generated by the Black Power movement in the Americas (from the United States to Trinidad) were in the air, as were the primarily youth-driven 1968 uprisings that rocked cities from Mexico City and Dakar to Lahore and Rio de Janeiro. Anti-colonial wars in Vietnam and Algeria were a key influence in the Paris uprising, where there was an alliance between workers and students. As the scholar Kristin Ross writes, this enabled ‘unforeseen alliances and synchronicities between social sectors and between very diverse people working together to conduct their affairs collectively’.5

In the same year, Biko led the formation of the South African Students’ Organisation (Saso), a Black student group. Headquartered in Durban, it incubated ideas that came to define the Black Consciousness Movement. Barney Pityana, a leading figure in Saso, recalled ‘long hours of interaction and debate among friends’ during which Biko ‘listened and challenged ideas as they emerged, concretised them, and brought them back for further development’.6

David Hemson (second from the left), Harriet Bolton (far right), and textile workers Joyce Gumede (second from the right) and Desmond Matabela (far left) attend a strike meeting in Bolton Hall.

(Credit: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.)

Biko is well known for sparking engagement with ideas of Black Power, Caribbean radicalism, and African nationalism. However, he is less well known for introducing Paulo Freire’s ideas to South Africa, ideas that were widely taken up by radical academics and students in Durban, including Turner when he arrived in the city in 1970.7

A Return to Labour Militancy

In 1969, dockworkers in Durban went on strike and were met with swift repression at gunpoint. Around 2,000 dockers were dismissed and forced onto trains that took them back to rural areas. In 1971, they threatened another strike. In neighbouring South West Africa (now Namibia), which was ruled by South Africa at the time, a general strike was organised in December of the same year, and strikes continued until April 1972. It was clear that the period of labour quiescence was coming to an end.

A confluence of factors battered the apartheid economy in the early 1970s, including a drop in international oil production, higher oil prices, and the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank delinking the U.S. dollar from the gold standard. The vast majority of African households were living in poverty, and an increase in rail fares compounded the situation.

On 23 February 1971, more than 24,000 workers walked out of clothing factories in and around Durban, and many participated in a mass meeting held at the Curries Fountain sports ground, a storied site in the history of popular organisation. Employers, unable to resort to disciplinary action due to the scale of the walk out, quickly agreed to the workers’ demand for a 20 per cent wage increase.

After the strike in the clothing factories, two students in Turner’s orbit, Halton Cheadle and David Davis, along with David Hemson, a young academic and committed militant, sought to connect with the growing labour militancy. The group was approached by Harriet Bolton, who had helped organise the Curries Fountain meeting and was part of the Garment Workers’ Industrial Union (GWIU), an Indian union. Her attempts to include African workers in unions had been rebuffed by the white leaders of the Trade Union Council of South Africa (Tucsa). In 1974, Bolton would lead the GWIU’s departure from the council. She approached Turner for help and, working closely with Hemson, they decided to offer union jobs to radical students. The students engaged workers and unions in various ways, including undertaking research related to wages and producing Isisebenzi (‘The Worker’), a newspaper that published interviews with workers, as well as more wide-ranging articles derived from the practice of careful listening.

Dockworkers struck again in 1972. Contrary to the idea that renewed labour militancy in the early 1970s was entirely ‘spontaneous’, Hemson has noted that various letters and pamphlets that appeared before and during the strike ‘provided concrete evidence of an underground network which did not declare itself even when open trade unionism started among dockworkers’.8

When dockworkers went on strike again in 1972, they were not only defying their white bosses: the strike was also a challenge to traditional authority, which, in a standard technique of colonial domination, was integrated into the domination of labour along with broader African life. In 1972, J.B. Buthelezi, the uncle of Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the reactionary Zulu nationalist organisation Inkatha, found his authority contested by dockworkers. One demanded to know ‘Who is this man, who elected him to represent us?’.9 Cheadle, who was at the meeting, recalled that when Buthelezi ‘got up to speak for the workers, they all shouted him down. It was absolute chaos’. Morris Ndlovu, a dockworker, affirmed: ‘It was at that meeting where we realised our power because we were talking for ourselves’.10

The situation came to a head in early 1973. On 9 January, African workers in factories across the city went on strike to demand pay increases, in many cases by two to three fold. They woke at 3 am and made their way to a nearby football stadium, chanting, as they moved through rush hour traffic, ‘Ufil’ umuntu, ufile usadikiza, wamthint’ esweni, esweni usadikiza’ (‘A person is dead, but their spirit still lives; if you poke the iris of their eye, they still come alive’). Hemson recently recalled that day in moving prose:

Out of the dawn they streamed, from the barrack-like hostels of Coronation Bricks, the expansive textile mills of Pinetown, the municipal compounds, great factories, mills and plants and the lesser Five Roses tea-processing plant.

The downtrodden and exploited rose to their feet and hammered the bosses and their regime. Only in the group, the assembled pickets, the leaderless mass meetings of strikers and the gatherings of locked-out workers did the individual have an expression of confidence.11

The moment had the feel of a general strike and opened the way for the ructions to come. Writing in early 1974, Sam Mhlongo, a medical doctor who had been imprisoned on Robben Island as a teenager, observed that ‘this strike, although settled, had a detonating effect’.12

The bosses blamed ‘agitators’ and ‘intimidation’ and threatened severe punishment against ‘ringleaders’. They refused to negotiate with the workers, called the riot police, and insisted that the workers elect a committee of representatives. Following a long history of dockers’ struggles in Durban, the workers refused. The Zulu king, Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu, arrived and appealed to the crowd to return to work, promising to negotiate on their behalf. He also cynically sought to divert vertical conflict between African workers and white bosses onto a more horizontal plane by dividing Indian and African workers.13

By the end of the month, workers in around 100 factories and other workplaces went on strike, including more than 6,000 workers at the notoriously exploitative Frame Group, at the time one of the largest textile companies in the world. In the words of one worker, ‘Although I make blankets for Mr. Philip Frame, I can’t afford blankets for my own children’.14 The police beat and detained some of the strikers, but despite the repression, strikes cascaded up and down the coast and as far inland as Pietermaritzburg, affecting the docks, mills, manufacturing, and transport industries. Many Indian workers joined the strikes, and the consistent demands from the bosses to elect representative committees were refused.

On 5 February, 3,000 municipal workers, African and Indian, walked off the job; by 7 February, this number rose to 16,000. Municipal work was classified as an essential service, and so the strike was considered illegal. Rubbish was not collected, graves were not dug, and food was left to rot as the municipal market and abattoir shut.

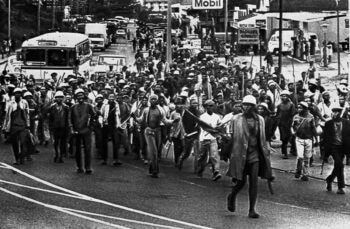

Workers began to march through the city under observation from police on the streets and helicopters in the air. The presence of rebellious workers on the streets became a symbolically insurgent presence in the apartheid city. At the end of March, estimates of the number of workers that had gone on strike ranged from 65,000 to 100,000 across more than 150 factories and workplaces.

Coronation Brick workers march along North Coast Road in Durban, led by a worker waving a red flag.

(Credit: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.)

Unions were formed at a rapid clip in the chemical, garment, metal, and textile industries. As workers began to unionise, there was a terrible incident at Prilla Mills in Pietermaritzburg, where the brutal labour regime was rooted in systemic sexual abuse as well as child labour (which was highly unusual in urban South Africa). Princess Osman, the leading organiser at the mills, was attacked on her way home and her face disfigured with acid.15

Educating the Educators

The strikes began with an affirmation of humanism, a politics that exceeded the demand for wage increases. There were also public hints of a connection to the national liberation struggle, with workers singing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika (‘God Bless Africa’), a Christian hymn that had become an anthem for the nation being forged in struggle. As Hemson observed, ‘The workers started to talk about [the African National] Congress. If you went to their homes at night, they would dig up the floorboards and bring out old ANC pamphlets’.16

Edward Webster, who arrived in Durban in February 1973 to take up an academic post, recalled that the working class ‘was not some collective tabula rasa waiting for white intellectuals to tell them what to think. They had their own history and political traditions… [including] the national political tradition [which] had deep roots in Durban and its surrounding areas’.17 However, some university-trained intellectuals were unable to understand that workers had entered into open contestation with their own political histories and ideas. This tendency, which remains common today, is exemplified by the reaction of an influential radical white academic to a survey of workers. When the survey results showed that Moses Mabhida, a trade unionist and communist who had gone into exile a week after the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, was one of their most respected leaders, the academic declared that no such person existed and that the survey must have been fabricated.18

Connections to the national liberation movement were not only at the level of ideas; there were also personal connections. For example, Harold Nxasana, a former Sactu militant and political prisoner who was active in the labour milieu in the early 1970s, was employed in one of the organisations set up by university radicals to service the labour movement.

Hemson has noted that Turner and Biko, and many of their followers, did not grasp the enduring power of the national liberation struggle and its close ties to the ANC. However, in the years since, several scholars have come to recognise that this tradition maintained a strong presence among workers. As a result, workers’ commitment to the ANC tradition in the 1970s is now much better understood.

The enduring tendency to overlook rich political traditions among the oppressed underscores that ‘it is essential to educate the educator himself’, as Karl Marx wrote in Theses on Feuerbach.19 Hemson has made an important observation in this regard:

In truth, the ‘teachers’ had much to learn about the militancy of women workers; existing networks in the workplace and society; the underlying loyalty to the ANC when there was the opportunity to safely express this; the spirit of the Mountain (of rural armed resistance against chieftainship in Pondoland); the militancy of many migrant workers; how to struggle for reforms without becoming reformist; how to exercise leadership without tutelage; and what approaches to adopt to maintain workers’ control over leadership in the union.20

Vusi Shezi, who went on to become an organiser with the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) and whose frustration with management’s treatment of him and his co-workers led him to join the 1973 strikes, also spoke to broader anti-colonial motivations behind the strikes, recalling an event where his anti-colonial perspective got him in trouble with the bosses, who in turn reassigned him to more demanding work:

I was working the night shift… I was saying to myself, ‘I am wasting my time and I am not studying. If I was using this time to study… but I don’t have books’… Then I started writing on the big trolley… taking a piece of chalk, what I know about the arrival of the whites starting in 1652 and how South Africa was colonized… Unfortunately, I forgot to wipe it off. Then the next morning, it was seen by senior management. They see this trolley with a very good map of Africa, and some background on colonialism, with a bit of an attack on the apartheid government and complaints about black leaders that were jailed.21

But, of course, enduring commitments to the national struggle did not overshadow that fact wages were a critically important issue in the 1973 strikes. Speaking in the heat of the strikes, one worker declared, ‘The child that does not cry dies… we should cry for ourselves for working hungry’.22 Another remarked, ‘Our bosses go in Mercedes cars, yet their workers do not even have overalls for work’.23 Other workers reported that they had to use loan sharks to get through the month. The bosses, the white media in Durban, and the Afrikaner nationalists who held state power largely abandoned their simultaneously paranoid and comforting fantasies about ‘agitators’, ‘communist plots’, and ‘overseas influence’ and settled on the idea that the strikes were strictly about wages rather than a wider political project.

Reports on the strikes from the Institute for Industrial Education founded by Turner and others in May 1973 and in the Black Review, a publication initiated by Biko in the same year as a project of Black Community Programmes, also looked at the strikes in solely economic terms, as a question of wages.24 The historian Julian Brown has argued that this understanding likely resulted in the state not resorting to the kind of intense violence and large-scale repression it had previously used against mass mobilisation. This insight generates another: it may have been tactically useful for the workers to avoid directly political issues in their public speech while sustaining a more political understanding in private speech.

Brown also notes that white elites frequently saw the strike in ethnic terms, as an outcome of a particular Zulu history and culture. But of course, as he observes, the strikes included Indian and African workers, and Africans of various ethnicities, including Pondo and Shangaan workers. Moreover, the interpretation of the strikes through a masculinist understanding of Zulu culture could hardly account for the many women who came to the fore, including Indian women in some factories.

Hemson has reminded contemporary audiences that Turner made a fundamental political mistake in aligning with the reactionary ethnically constituted organisation Inkatha, which, he argues, Turner misunderstood as an at least potentially progressive movement of the rural poor. In contrast, he notes that Biko was very clear on the collaborationist character of Inkatha. In the 1980s, it would violently attack the labour movement, and, in 1989, murder one its great woman leaders, the Numsa shop steward Jabu Ndlovu.

Some academic work has, explicitly or implicitly, ascribed the deliberative collective practices and formal democratic commitments that emerged from the Durban strikes and characterised the union movement for decades to come to the involvement of mostly white intellectuals inspired by the New Left in Western Europe and North America. This eviscerates a well-known history of collective practices of deliberative consensus-seeking rooted in rural life that has long shaped myriad struggles by workers and others. This history is well described in the work of T. Dunbar Moodie and Vivienne Ndatshe on migrant workers in the Johannesburg gold mines.25 It was highlighted by Nelson Mandela in his statement from the dock in 1962 when he argued that the ‘seeds of revolutionary democracy’ lay in the councils, known as Pitso, Imbizo, or Kgotla, through which rural communities, following pre-colonial practices, governed themselves.26 Describing the practices in these councils as ‘democracy in its purest form’, Mandela explained that, there, everyone could speak, and ‘meetings would continue until some kind of consensus was reached’.27

This collective and carefully deliberative search for consensus remains a constitutive force in the contemporary movement of the urban poor Abahlali baseMjondolo (meaning ‘residents of the shacks’), which emerged in Durban in 2005 and today has more than a 100,000 members. The same is true of the African humanism manifest in the moment of rupture on factory floors in Durban in 1973, as powerfully expressed by Emma Mashinini, a leading trade unionist in the 1980s: ‘I am human. I exist. I am a complete person’.28 The oppressed do not enter the political terrain without pre-existing ethical and political commitments, practices, and memories.

Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu addresses Coronation Brick workers in Durban North, January 1973.

(Credit: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.)

The democratic character of the labour movement that emerged from the Durban Moment is best understood as a productive encounter, what Fanon called ‘a mutual current of enlightenment and enrichment’ between university-trained intellectuals and working-class militancy.29

After the Durban Moment

In March 1973, Biko and Turner were both banned, the former exiled to his hometown in the Ciskei Bantustan and the latter to his home in a white working-class Durban suburb. Hemson, who had helped found dock, furniture, and metalworker unions in the first three months of 1973, was banned the following year.

On 25 September 1974, Saso organised a rally at Curries Fountain in solidarity with the Liberation Front of Mozambique (Frelimo), whose struggle for independence in Mozambique was nearing its conclusion. The event was banned the day before it was scheduled, but 5,000 people turned up and the atmosphere of defiance was electric. The police disrupted the rally, and nine Saso activists were arrested, tried, and jailed. The arrests brought the period of political innovation that scholar Tony Morphet famously called the ‘Durban Moment’ to an end.30 In September 1977 Biko was murdered by police, and Turner was assassinated in January of the following year.

After the successes of the 1973 strikes, workers became increasingly conscious of their position as the industrial proletariat driving the industrial economy. They were more aware of their power and the fact that employers could not easily dismiss large swathes of the semi-skilled workforce. In addition, more women began to emerge as union leaders: in 1975, Emma Mashinini founded the South African Commercial, Catering, and Allied Workers’ Union (Saccawu) in Johannesburg, and Jabu Ndlovu would become a powerful leader in the Metal and Allied Workers’ Union (Mawu) and then Numsa in the 1980s.

In June 1976, a series of protests led by Black school children against both apartheid education and the wider system of oppression was met with murderous repression. The Soweto uprising, as it came to be known, shifted the primary locus of resistance to Johannesburg and ignited a national turn to open revolt. In 1979, Black trade unions were legalised, and many of those that emerged after the Durban Moment came together through the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu) in Hammanskraal, north of Johannesburg.

Fosatu was committed to workers’ control of unions and on the shop floor, as well as the empowerment and education shop stewards. There was a clear sense that the democracy being developed in the labour movement would, in time, become the nucleus for the democratisation of society. This was expressed in the slogan ‘Building tomorrow today’.31 Like the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union before it, Fosatu undertook impressive cultural work including organising theatre, poetry, and choir projects. Again there were productive connections between grassroots militants and university-trained intellectuals. Ari Sitas, an academic in Durban, played an important role in the explosion of cultural work and innovation in unions. Alfred Temba Qabula, a migrant worker from emaMpondweni who had participated in the 1959 peasant uprising known as the Pondo Rebellion as a teenager and joined Mawu while working at the Durban Dunlop factory in the early 1980s, became known among unions and the broader progressive movement as a renowned poet.

A famous speech, discussed and drafted by many and delivered in 1982 by the Fosatu Secretary-General Joe Foster, made a strong argument for the organisational autonomy of labour from the national liberation movement:

Workers must strive to build their own powerful and effective organisation, even while they are part of the wider popular struggle. This organisation is necessary… to ensure that the popular movement is not hijacked by elements who will, in the end, have no option but to turn against their worker supporters.32

Although Fosatu was a powerful force, it was unable to unite all the unions in one federation. The first moment of unity in action across the progressive labour movement took place when the radical doctor and trade unionist Neil Aggett, an organiser for the African Food and Canning Workers’ Union, was murdered in police detention in 1982. In response, unions across the country went on strike, opening new possibilities to forge the wider unity that was to come.

The historian Jabulani Sithole writes that Sactu began to encourage its ‘underground operatives to infiltrate them [unions] with the aim of undermining them from within if they were regarded as reactionary, or in order to take them over if they were deemed progressive’.33 Between 1981—1985, Sactu underground operatives Samuel Bhekuyise Kikine, Thobile Mhlahlo, Sydney Mufamadi, Samson Ndou, Themba Nxumalo, Matthew Oliphant, and others participated in building unity among a range of unions.

The high levels of organisation first built on the shop floor began to move into wider society. On 20 August 1983, the United Democratic Front (UDF) was launched in Mitchells Plain, Cape Town. Hundreds of organisations became affiliated with the UDF, including unions; youth, women’s, and student organisations; religious groups; and professional associations. In a famous speech from 1987, UDF leader Murphy Morobe affirmed its commitment to radical democracy in clear terms: ‘we are talking about direct as opposed to indirect political representation, mass participation’.34 Many commentators who were in or close to the UDF argued that its formally organised democratic practices were drawn from trade union experiences.

However, the relationship between the UDF and the union movement was not uncomplicated. There was a significant degree of distrust between the unions aligned with the UDF and the Fosatu unions that remained independent from it. This escalated a simmering debate between two factions of the radical intelligentsia, who described each other (but not themselves) as either ‘workerists’ or ‘populists’. The workerists wanted the union movement to remain independent of the ANC so that it could sustain the autonomy of organised working-class power from the multi-class national liberation movement. The populists saw white supremacy as the primary problem confronting Black people across class and wanted to marshal maximum unity in the struggle for national liberation.

The workerists dominated Fosatu until 1985, when a new and much bigger federation—the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu)—was formed and launched in Durban at Curries Fountain following a process of unity summits and meetings that had begun in 1981. The balance of power had shifted to the populists. Fosatu dissolved into Cosatu, which explicitly allied itself with the UDF, and later, the ANC.

But, notably, the expression of the national tradition associated with the ANC and now expressed in Cosatu had, in important respects, been shaped by the Durban Moment, including ideas of worker control and Black Consciousness. Jay Naidoo, the first general secretary of the new federation, recalls first being radicalised at a stirring public meeting led by Biko in an Indian neighbourhood in Durban.35 Cosatu rapidly became extraordinarily powerful in workplaces and wider society and, along with the UDF, made significant and decisive contributions to the collapse of the apartheid regime.

In 1990, the apartheid state began to concede that a shift to some form of democracy, limited of course to liberal democracy, was inevitable. The Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani has argued that ‘The most important force for this change was not the armed struggle, nor exile politics, nor the international boycott movement’, but rather the political work of ‘student activists of all colours and by migrant and township labour’.36

The democratic popular politics with their roots in the Durban strikes were not entirely forgotten as apartheid gave way to a new order. As Mashinini insisted, ‘When we elect leaders to be public representatives, we do not mean that they have divine rights to rule us. They are servants of the people and must accept that we have a right to criticise them. That’s what we learnt from the trenches of the labour struggle that dealt a death blow to apartheid’.37

However, the socialist hopes of the unions gave way to deep disappointments resulting from the accommodation between capital, white power, and national elites. As Qabula, the most compelling voice among the worker poets, lamented, ‘Slovo and Hani saw red everywhere… But Tutu and the Bishops… saw rainbows’.38 In 2002, he died in poverty, like so many others who were on the frontlines of struggle. He left these haunting lines:

we are the movable ladders

that take people up towards the skies,

left out in the open for the rain

left with the memories of teargas, panting for breath.39

A section of the crowd of striking Coronation Brick workers in Durban North, January 1973.

(Credit: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries.)

The Durban strikes, and the workers’ struggles that built a powerful trade union movement in their wake, were not given their rightful place in official memory. Today, they are seldom remembered outside of union circles.

The sometimes bitterly personal and sectarian battles that have been waged in academic journals over which political forces—workerists, populists, Black Consciousness activists, white intellectuals, or operatives in the ANC underground—should be credited for both the wider Durban Moment and for building the post-strikes union movement have not helped matters. On the contrary, this contestation has often taken the form of an intra-elite battle.

The workers who built democratic forms of counter-power from within a deeply oppressive society, eventually bringing down that system, are seldom given full acknowledgement and respect. Their history still awaits an adequate telling.

Notes:

- ↩ Tricontinental, A Brief History of South Africa’s Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (1919-1931).

- ↩ Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 75.

- ↩ Richard Turner, The Eye of the Needle, 65.

- ↩ More, Biko: Philosophy, Identity and Liberation.

- ↩ Ross, May ‘68 and Its Afterlives, 7.

- ↩ Macqueen, Black Consciousness, 105.

- ↩ Tricontinental, Paulo Freire and Popular Struggle in South Africa.

- ↩ Cole, Dockworker Power, 180.

- ↩ Davie, Poverty Knowledge in South Africa, 190.

- ↩ Cole, Dockworker Power, 179.

- ↩ Hemson, ‘Freedom’s Footprints: Freire and Beyond’.

- ↩ Mhlongo, ‘Black Workers’ Strikes in South Africa’, 41—49.

- ↩ Brown, The Road to Soweto, 84.

- ↩ Institute for Industrial Education, The Durban Strikes 1973.

- ↩ Hemson, The 1973 Natal Strike Wave.

- ↩ Hemson, The 1973 Natal Strike Wave.

- ↩ Webster, ‘Exodus Without a Map’.

- ↩ See, among other accounts by Webster, ‘Exodus Without a Map’.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach.

- ↩ Hemson, ‘Freedom’s Footprints’.

- ↩ Davie, Poverty Knowledge in South Africa, 195.

- ↩ Brown, The Road to Soweto, 94.

- ↩ Davie, Poverty Knowledge in South Africa, 194.

- ↩ Institute for Industrial Education, The Durban Strikes, 1973; Black Community Programmes, Black Review; Tricontinental, Black Community Programmes.

- ↩ Moodie with Ndatshe, Going for Gold.

- ↩ Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, 64.

- ↩ Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, 64.

- ↩ Mashinini, Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life, 27.

- ↩ Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 143.

- ↩ Morphet, ‘Richard Turner: A Biographical Introduction’, in Turner, The Eye of the Needle.

- ↩ Friedman, Building Tomorrow Today.

- ↩ Foster, The Workers’ Struggle.

- ↩ Sithole, ‘Contestations Over Knowledge Production or Ideological Bullying?’, 231.

- ↩ Morobe, ‘Towards a People’s Democracy: The UDF view’.

- ↩ Naidoo, Fighting for Justice. 33—34.

- ↩ Mamdani, Neither Settler Nor Native, 164.

- ↩ Mashinini, Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life, xvii.

- ↩ Qabula, Collected Poems, 87.

- ↩ Qabula, Collected Poems, 86.

Bibliography:

Black Community Programmes. Black Review. Durban: Black Community Programmes, 1974.Brown, Julian. The Road to Soweto: Resistance and the Uprising of 16 June 1976. Johannesburg: Jacana, 2016.

Callebert, Ralph. On Durban’s Docks: Zulu Workers, Rural Households, Global Labour. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2018.

Cole, Peter. Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area. Champagne: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Davie, Grace. Poverty Knowledge in South Africa: A Social History of Human Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Dunbar Moodie, T. with Vivienne Ndatshe. Going for Gold: Men, Mines and Migration. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Fairburn, Jean. Flashes in Her Soul: The Life of Jabu Ndlovu. Johannesburg: Fanele, 2018.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin, 1976.

Foster, Joe. The Workers’ Struggle: Where Does Fosatu Stand? Durban: Fosatu Printing Unit, 1982.

Friedman, Steven. Building Tomorrow Today: African Workers in Trade Unions 1970—1984. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1987.

Hemson, David. Class Consciousness and Migrant Workers: Dock Workers of Durban. PhD diss., University of Warwick, 1979.

Hemson, David. ‘Freedom’s Footprints: Freire and Beyond’. New Frame, 27 October 2020. www.newframe.com.

Hemson, David. The 1973 Natal Strike Wave: How We Rebuilt the Unions. Durban: Congress Militant, 1990.

Institute for Industrial Education. The Durban Strikes 1973: Human Beings with Souls. Durban: Institute for Industrial Education, 1974.

Macqueen, Ian. Black Consciousness and Progressive Movements under Apartheid. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press, 2018.

Mamdani, Mahmood. Neither Settler Nor Native. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2020.

Mandela, Nelson. Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. New York: Little, Brown & Company, 1994.

Marx, Karl. Theses on Feuerbach. 1845. www.marxists.org.

Mashinini, Emma. Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life. Johannesburg: Picador, 2012.

Mhlongo, Sam. ‘Black Workers’ Strikes in South Africa’. New Left Review 1, no. 83 (January—February 1974): 41—49.

More, Mabogo. Biko: Philosophy, Identity and Liberation. Pretoria: HSRC Press, 2017.

Morobe, Murphy. ‘Towards a People’s Democracy: The UDF view’. New Frame, 15 November 2018. www.newframe.com.

Naidoo, Beverly. Death of an Idealist: In Search of Neil Aggett. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2012.

Naidoo, Jay. Fighting for Justice. Johannesburg: Picador, 2010.

Qabula, Alfred Temba. A Working Life: Cruel Beyond Belief. Johannesburg: NUMSA, 1989.

Qabula, Alfred Temba. Collected Poems. Cape Town: South African History Online, 2016.

Qabula, Alfred Temba, Mi S’dumo Hlatswayo, and Nise Malange. Black Mamba Rising: South African Worker Poets in Struggle. Durban: Worker Resistance and Culture Publications, 1986.

Ross, Kristen. May ’68 and Its Afterlives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Sithole, Jabulani. ‘Contestations Over Knowledge Production or Ideological Bullying?: A response to Legassick on the Workers’ Movement’. Kronos 35, no. 1 (2009): 222—241.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. A Brief History of South Africa’s Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (1919—1931). Dossier 20, 3 September 2019.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Paulo Freire and Popular Struggle in South Africa. Dossier 24, 9 November 2020. thetricontinental.org.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Black Community Programmes: The Practical Manifestation of Black Consciousness Philosophy. Dossier no. 44, 10 September 2021. thetricontinental.org.

Turner, Richard. The Eye of the Needle: Towards participatory democracy in South Africa. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1980.

Webster, Edward. ‘“Exodus Without a Map”: What Happened to the Durban Moment?’. SA History Online, 2022.