“Nicaragua Frees Hundreds of Political Prisoners to the United States,” the New York Times (2/9/23) reported. In an unexpected move on February 9, the Nicaraguan government deported to the United States 222 people who were in prison, and moved to strip them of their citizenship. The prisoners had been convicted of various crimes, including terrorism, conspiracy to overthrow the democratically elected government, requesting the United States to intervene in Nicaragua, economic damage and threatening the country’s stability, most relating to the violent coup attempt in 2018 and its aftermath.

The New York Times (2/9/23) reports that Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega “rose to power after helping overthrow another notorious Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza, in 1979.”

President Daniel Ortega explained that the U.S. ambassador had unconditionally accepted an offer to send the 222 “mercenaries” (as Ortega called them) to Washington. Two others opted to stay in prison in Nicaragua, and an additional four were rejected by the U.S.

Despite the Times’ relatively benign headline, its story was heavily weighted against a country that had “slid into autocratic rule,” and whose government had “targeted opponents in civil society, the church and the news media.” For the Times, the “political prisoners” were not criminals but “opposition members, business figures, student activists and journalists.”

For the Washington Post (2/9/23), they included “some of Nicaragua’s best-known opposition politicians” and “presidential hopefuls.” Their release had “eased one of Latin America’s grimmest human rights sagas.” It added that “several of the prisoners had planned to run against Ortega in 2021 elections, but were detained before the balloting.”

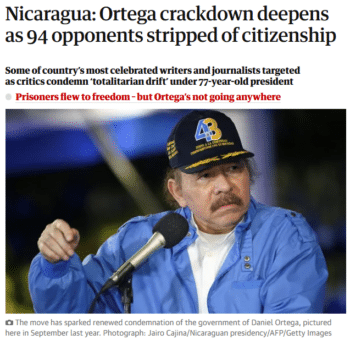

The Guardian (2/9/23) blamed the imprisonments on “Nicaragua’s authoritarian regime” and its “ferocious two-year political crackdown,” intended to “obliterate any challenge” before the last presidential election in 2021.

Bad when they do it

The corporate media were given a second bite of the cherry when the Nicaraguan government announced, six days later, that it was rescinding the citizenship of a further 94 people, most of them living abroad, in some cases for many years. The list included such notable names as authors Sergio Ramírez and Gioconda Belli. The Times (2/17/23) quoted the United Nations refugee agency as saying that international law “prohibits the arbitrary deprivation of nationality, including on racial, ethnic, religious or political grounds.” For the Guardian (2/16/23),

Daniel Ortega’s authoritarian regime has intensified its political crackdown.

The Guardian (2/16/23) did not note that the British government has stripped at least 767 people of citizenship since 2010.

Neither mentioned that law in the U.S. and Britain, and other countries, permits the revocation of citizenship in the U.S. for, among other things, engaging in a conspiracy “to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States,” and in Britain of “those who pose a threat to the country.” The British government has made orders to deprive at least 767 people of citizenship since 2010.

There are other important considerations that apply in Nicaragua’s case, which the media ignore. First, it is a small country, with limited means to defend itself, that has been the subject of U.S. intervention for decades—militarily in the 1980s, politically more recently, and economically since sanctions were imposed in 2018. Those calling for even stronger U.S. pressure (e.g., curbs on trade) are putting the well-being of Nicaraguans at real risk.

Second, there is a precedent for a country’s unelected citizens being recognized as its “real” government by the U.S. and its allies, in the case of self-proclaimed “president” Juan Guaidó in Venezuela, a gambit that successfully stole the country’s assets (Venezuelanalysis, 1/11/22), even though it did not provoke the hoped-for military coup (FAIR.org, 5/1/19). The possibility of similar tactics being used against Nicaragua might well have been a factor influencing the action it took.

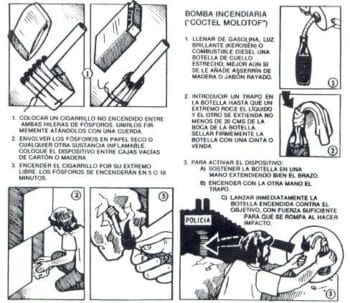

In 1983, the CIA wrote a manual, Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare, that advised Nicaraguans fighting the Sandinistas to lead “demonstrators into clashes with the authorities, to provoke riots or shootings, which lead to the killing of one or more persons, who will be seen as the martyrs; this situation should be taken advantage of immediately against the government to create even bigger conflicts.”

The corporate media’s accounts of the Nicaraguan government’s reasons for the deportations and cancellations of citizenship were both perfunctory and disparaging. For example, the Guardian’s second article (2/16/23) said the government “called the deportees, who were also stripped of their citizenship, ‘traitors to the motherland.’” The rest of its article was given over to criticism of the Ortega government.

The New York Times (2/9/23) quoted Nicaraguan journalist Carlos Chamorro, one of the 94, as saying, “All prisoners of conscience are innocent.” It made no assessment of his claim.

The Washington Post (2/9/23) did include Ortega’s criticism of U.S. financing of opposition groups: “These people are returning to a country that has used them…to sow terror, death and destruction here in Nicaragua,” Ortega said. But it went on to report in its own voice that “Ortega crushed a nationwide anti-government uprising in 2018, the beginning of a new wave of repression.”

Three months of January 6

As FAIR has shown in a range of articles, media coverage of Nicaragua consistently presents the image of a country suffering extreme repression. The story of the 222 deportees was a further opportunity to repeat this treatment. For example, included in the Guardian’s coverage (2/16/23) was an official from Human Rights Watch saying, “The country is on the verge of becoming the Western Hemisphere’s equivalent of North Korea.” Whether it is the closure of NGOs, the results of the 2021 presidential election, the reasons for increased Nicaraguan migration to the United States, or the country’s response to Covid-19, corporate media ignore good news about Nicaragua, give prominence to the views of government opponents and, if Daniel Ortega is quoted, this is done in a disparaging way.

The most extraordinary example of this bias is the corporate media’s pretense that the “terror, death and destruction” of the 2018 coup attempt either never occurred or were perpetrated solely by the “authoritarian regime.” Yet there was ample evidence at the time, and since, of horrific acts of violence against police and Sandinista supporters. Examples can be seen in two short videos (warnings about content apply), here and here, which include clips made by opposition protesters themselves and uploaded to social media.

In the United States, the New York Times (12/19/22) does not express shock that people who try to overthrow the elected government are treated as criminals.

The uprising that shook Nicaragua lasted roughly three months, resulted officially in 251 deaths (including 22 police officers; others put the total deaths as higher) and over 2,000 injured. It allegedly “caused $1 billion in economic damages,” and led to an economic collapse. (After years of growth, GDP fell by 3.4% in 2018).

The coup attempt led to at least 777 arrests, with many of those convicted given lengthy prison sentences. But importantly, and mostly ignored by the corporate media, 492 prisoners were released between mid-March and mid-June 2019.

Nicaragua’s experience in 2018 stands comparison with the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, and the response to it by the U.S. justice system, generally with the corporate media’s support. The siege of the Capitol lasted only a few hours and led to five deaths, about 140 injuries to police and $2.7 million in damage. Reporting uncritically on the sanctions against those responsible, the New York Times (12/19/22) said that more than 900 people had been charged so far, facing prison sentences of up to ten years.

Later, the Times (1/23/23) reported that four culprits had been charged with “seditious conspiracy,” under a statute dating from the civil war period. In words not dissimilar to those used by the Nicaraguan judge who announced the order stripping 94 people of citizenship, one of the prosecutors was quoted as saying that the defendants “perverted the constitutional order.” He added that they “were willing to use force and violence to impose their view of the Constitution and their view of America on the rest of the country.” Unlike the Times’ reports on Nicaragua, there is no hint of criticism of these charges, nor questioning of whether they are justified.

Evidence of wrongdoing

William Sirias Quiroz testified that Medardo Mairena, one of the prisoners deported by Nicaragua, personally supervised his torture at the hands of opposition militants, saying, “We have to make an example of this one.”

This is the context in which the 222 supposedly “innocent” people released into the United States had been charged and found guilty during 2021 and 2022. Questions about the wrongdoing of the 222 were set aside in corporate media coverage, yet it would have been easy to find evidence of wrongdoing. Here are three examples:

- Cristiana Chamorro headed an NGO, the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation, that received $76 million from USAID. This was used to influence Nicaragua’s elections via an array of opposition media outlets, several owned by the Chamorro family. She refused to comply with transparency laws and closed her foundation; she was then convicted of money laundering.

- Félix Maradiaga was convicted of treachery because he had pleaded for economic sanctions against Nicaragua.

- Medardo Mairena and Pedro Mena had organized a range of armed attacks in 2018, for which they had been pardoned in the 2019 amnesty. These included the siege of the police station in Morrito on July 12, 2018, in which five people were killed. Both were later convicted again for further offenses. In 2020, a large number of victims provided evidence of the violence directed by Mairena and his associates in 2018 in the central region of Nicaragua.

For U.S. corporate media, none of this was relevant. The real reason for the original arrests in 2021 was simple: Ortega expected to lose that year’s election, so he locked up his opponents.

It is true that several of those imprisoned had expressed interest in running. But in a joint post-election analysis with journalist Rick Sterling, I argued that they would have had little chance of taking part, much less of winning.

However, according to the Washington Post (2/9/23), this meant that Ortega, “essentially unopposed, cruised to a fourth consecutive term.” In fact, he won 76% of the vote on a 65% turnout, standing against five others, including two candidates from parties that had been in government in the years before Ortega returned to power.

‘A terrible place’

Why were the prisoners released? The Post admitted that there had been no “quid pro quo,” but then carried a quote claiming that Ortega was “buying some breathing room internationally.”

Travel + Leisure (4/29/22) praises Nicaragua as “home to a rich cultural heritage and friendly locals who go out of their way to get you the most delicious seafood, help you catch a wave, or show you the way around the backroads.”

The New York Times reported that the releases “bolster the argument that sanctions are effective,” linking this to its portrayal of Nicaragua as an authoritarian regime:

The sanctions have also stretched the government’s ability to pay off pro-Ortega paramilitaries or expand the police force to manage dissent.

Not that sanctions would be relaxed, of course: “Officials…said they would continue to apply pressure to the Ortega administration,” the paper reported, as “the Biden administration does not believe that ‘the nature of the government’ has changed.” Dan Restrepo, President Obama’s national security adviser for Latin America, declared,

Nicaragua remains a terrible place for Nicaraguans, and a lot more has to change.

Readers of the corporate media who are unfamiliar with Nicaragua receive impressions of the country, reinforced with every news item, that it is a “terrible place,” in the grip of a police state. As someone who lives in the country, I find a huge disjuncture between these descriptions and the reality of Nicaraguan daily life.

Readers of the Times or the Post might be surprised to hear Nicaragua was recently judged to be the place in the world where people are most at peace (CNBC, 1/7/23). InSight Crime (2/8/23) ranked it the second-safest country in Latin America, according to reported data on homicides. It tackled Covid-19 more successfully than its neighbors, and has the highest vaccination rate in the region. Websites devoted to tourism dub it a favorite destination in Central America and extol its friendliness.

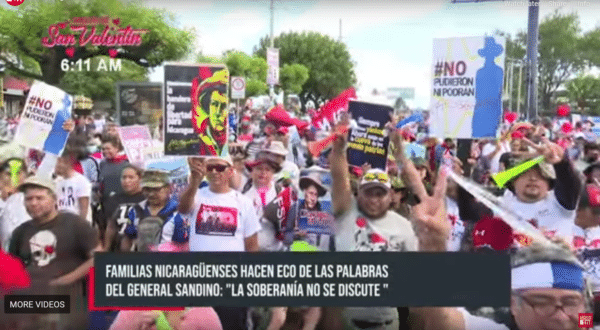

Finally, the government’s decision to deport the 222 was popular in Nicaragua itself, at least among government supporters. There were enthusiastic demonstrations in at least 30 cities the following weekend, including the one where I live. Unpersuaded, the British Independent (2/12/23) said that the “Sandinista political machine mobilized a few thousand of its faithful.” They must not have seen the reports from the capital, Managua, where tens of thousands filled the streets.