In 1973, fifty years ago, Amilcar Cabral, the leader of the national revolution in Guinea and Cape Verde was murdered. For the next three weeks roape.net will be celebrating his contribution to radical political economy, Marxist and liberation politics in a series of blogposts. We will be republishing a tribute to Cabral that first appeared in our print journal thirty years ago.

Cabral was a unique thinker and fighter for African liberation, and emerged as a leading figure in the ‘second liberation’ struggles against Portuguese colonialism in the late 1960s and 1970s. Throughout the battle to liberate Guinea, Cabral argued for the need to detail one’s own reality and any revolution must be grounded in a concrete understanding of conditions on the ground.

Cabral’s Marxism emerged in part as a reaction to the failures of an earlier wave of national liberation in Africa. The apparent freedom of the first wave of independence had extended and, in some respects, strengthened foreign control of the continent.

Many activists saw in the revolutionary movements in Guinea and Cape Verde (and to some extent in Mozambique and Angola) examples of more participatory and democratic practice, that could be harnessed to provide a radical alternative for the continent. Cabral’s organisation PAIGC (the Partido Africano de Indendencia de Guine e Cabo Verde) was formed in 1956, and for a generation, came to express the hopes for real liberation across Africa.

In 1963 PAIGC embarked on a campaign to explain the realities of the anti-colonial struggle across Guinea which involved a fusion of ideas. Cabral spoke of a people’s culture developing as a result of the liberation movement, and emerging from the ‘masses in revolt’.

Speaking to supporters of Africa’s liberation, in America, and Europe, amid the Black Power movement and revolutionary upheavals across the global North and South, Cabral pushed further than any other figures of radical national liberation. Yet he was acutely conscious of the problems and limitations of the liberation he sought.

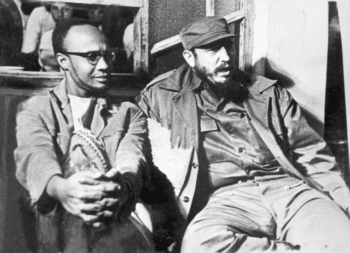

Amílcar Cabral with Fidel Castro in Cuba for the Tricontinental Conference. January 1966, Wikimedia Commons.

For Cabral what was done with the state after independence was a central question—the ‘fundamental one’ for him. He acknowledged that this was an issue that had never been satisfactorily answered, yet with brilliant insight he wrote: ‘It’s the most important problem in liberation movements. The problem is perhaps the secret of the failure of African independence’ (1977: 84).

Once independence was won these movements consolidated in the state. In the case of PAIGC after Cabral’s murder, and independence in 1974, the leaders of the party were compelled to take up the statist model of the Soviet Union and quickly transformed themselves into an exploiting class.

The petty bourgeoisie Cabral referred to in his 1966 paper The Weapon of Theory could not continue to identify ‘with the aspirations of the people’ (1969: 89). After independence these aspirations, like many others, were jettisoned. So the seemingly fluid and radical structures of the anti-colonial revolution hardened into a bureaucratic one-party state.

The short papers in this collection were edited by Mike Powell in 1993. Powell knew Guinea-Bissau and had worked with the radical historian of modern Africa, Basil Davidson, who also contributed to this collection. Powell was close to the politics and disappointments of the PAIGC in the 1970s. Today, we republish Mike’s introduction beneath this piece.

Next week, we will publish Lars Rudebeck’s celebration of Cabral’s extraordinary writing, speeches and interviews, including reflections on personal conversations Rudebeck held with Cabral at various points. While celebratory, and acknowledging that Cabral saw with remarkable prescience the eventual betrayal that would be handed down by the petty bourgeois leaders of the liberation struggle, Rudebeck also perceives in the writings and politics of Cabral inadequate attention to the post-colonial situation and the question of how to democratise power over the economy and transform the relations of production (a point on which Basil Davidson also agrees).

The following week, we look at Shubi Ishemo’s short study of Cabral’s thought and practice, and lessons for revolutionary movements. Ishemo notes Cabral’s stature as an agronomist, a revolutionary theoretician, a political strategist, and an historian. In Ishemo’s recollection of Cabral’s commitment to a rigorous historical approach as he sought to gain a concrete understanding of the social, economic, political, and cultural realities of Guinea and Cape Verde, we find echoes of the Guyanese revolutionary Walter Rodney who took a similar historically grounded approach and rigour to his own research and writing.

The Amilcar Cabral Foundation in Praia, the capital city of Cape Verde. 28 February 2015, Wikimedia Commons.

In the final week, we will be returning to Basil Davidson’s intimate political and personal portrait of Cabral, who Davidson knew during the 1960s and 1970s. Davidson’s piece contains fascinating detail and insight on Cabral’s principles of organising, as well as how Cabral and his comrades started their successful anti-colonial struggle in the early 1950s, all of which retains its relevance in the context of ongoing struggle and revolt across the continent today.

A Tribute to Amilcar Cabral, 12 September 1924–20 January 1973

Mike Powell

ROAPEs decision to mark the twentieth anniversary of the murder of Amilcar Cabral reflects the view that this is an opportune time to consider his achievements and the relevance of both his thought and practice–especially regarding events that are unfolding in Africa today. The contributions from Basil Davidson, Shubi Ishemo and Lars Rudebeck each provide a stimulating analysis that covers enormous ground but hardly overlaps at all.

One enduring relevance of the life of Cabral and of the struggle of the PAIGC (Partido Africano Pela Independencia de Guine e Cabo Verde) is its very success. When the Portuguese responded to a peaceful wage protest on 3 August 1959 by killing fifty dock workers, it must have been inconceivable to the survivors of Pijiguiti Quay that within sixteen years Bissau would be theirs–after defeating a 70,000 strong NATO supplied colonial army. These historical moments need, especially now, to be remembered.

Cabral’s own writing continues to be an invaluable source of inspiration. This is not to suggest, and Cabral himself would have hated the suggestion, that his writing formed some great dogma–the conclusions of which should be obediently followed. What they do provide is an astonishing range of insight and analysis. For instance, environmentalists may discover in his work and in particular his essay on ‘The Utilisation of the Land in Africa’ (first published in the Boletime Cultural da Guine and then in English in Ufuhamu, 1973), an early and possibly original analysis of the links between export-oriented production and soil erosion. As Rudebeck points out, Cabral saw theory not as any end in itself but as a highly practical tool for understanding and changing the reality he faced which was one of armed colonial domination. Soil erosion was important because it affected agricultural production.

The role of women was important because their support was vital to the struggle. From as early as the PAIGC’s First Congress in 1964, it was agreed that at least two of the five person committee which would be elected to run each village should be women. Cabral’s commitment to women’s participation did not stop at playing a numbers game. In informal interviews which are published in Return to the Source and with discussions with PAIGC militants such as those interviewed by Stephanie Urdang, it was clear that there was a need to understand the more subtle differences of perception and work towards accommodating them. By the end of the war, women were beginning to put forward their own proposals and did not, in the main, seem to feel they were pushing against closed doors.

According to Mario de Andrade (founder member of the PAIGC), the greatest danger for socialist governments was the failure of communication between the governors and the governed. Cabral clearly gained increasing satisfaction from the results of popular participation in the politics of the revolution, particularly the two-way process of education which was happening as the revolutionary petty bourgeois lived amongst the peasantry and together they shared the joy and the relief of winning a war. It was this shared experience, in the forest, in war, this forging of a common purpose which created the image of the local bourgeoisie changing sides, committing suicide as a class, a concept which has always given more sedentary Marxists conceptual headaches.

However, it is very important to note that Cabral was not simply assuming that all would work out smoothly. He was actively trying to build mass participation into the structures of the state that was being created and, more in interviews than in any major speeches, he appeared to be thinking increasingly of a very decentralised state. I remember one interview i in which he suggested that ministries would be spread around the country and that there would be no traditional capital city.

Cabral’s written and recorded work is important both historically and as a stimulus for creating new ideas. So also is his methodology, described in all the pieces which follow. It was a methodology which, for example, sought to understand ethnic differences through careful studies of how people live, and rather than hiding differences, sought ways for people to unite. It also made exhortations to ‘tell no lies, claim no easy victories’ which might appear banal but, if applied, gain real credibility for any political movement. Equally important in looking at Cabral’s achievements are the skills, in modern parlance, management skills developed during the struggle. As Basil Davidson records, the PAIGC’s ability to train cadres to overcome the warlordism of early years and successfully delegate authority, was vital to its success. In very different circumstances, such training and such delegation are central to any effort to launch a popular-based struggle today.

No direct parallels are being suggested. As Davidson points out, one of the advantages that the PAIGC had was an implacable enemy which left families no room for sitting on the fence. Many of the political struggles developing in Africa now offer far less simple options to the people around them. Cabral’s legacy is not a blueprint for these struggles. What is offered is a wonderful example of victory against the odds, a fountain of ideas, a way of approaching the problems that face us and the benefit of some very practical experience of how to organise.