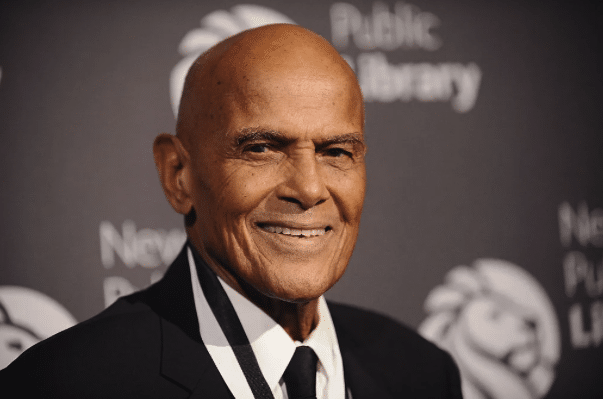

Iconic actor, musician, and lifelong activist Harry Belafonte has died at the age of 96. The cause, per his longtime spokesman Ken Sunshine, was congestive heart failure.

Belafonte’s singing shaped a musical consciousness for generations of Americans, from traditional folk music and spirituals to Caribbean calypso and protest songs. His acting in films such as “Carmen Jones” and “Odds Against Tomorrow” won praise and helped pave the way for Black performers who would follow. And his activism took him to the front lines of the civil rights movement, where he marched with Martin Luther King Jr., lobbied for the release of an imprisoned Nelson Mandela, and joined other stars to raise money for famine relief on the African continent. Realizing from an early age the power of celebrity to advance social change, Belafonte was among the rare few to have been equally entrenched in the worlds of entertainment and politics with genuine results to spare.

“I wasn’t an artist who’d become an activist,” Belafonte wrote in his 2011 memoir, “My Song.”

I was an activist who’d become an artist. Ever since my mother had drummed it into me, I’d felt the need to fight injustice wherever I saw it, in whatever way I could. Somehow my mother had made me feel it was my job, my obligation. So I’d spoken up, and done some marching, and then found my power in songs of protest, and sorrow, and hope.

Harry Belafonte was born Harold Bellanfanti Jr. in 1927 to Jamaican parents who had immigrated to New York City. Young Harry’s father, a man who was in and out of Harry’s life during his childhood, as a ship’s cook, was a violent man who beat his wife and son, sometimes with bloody results. His mother, Millie, eventually fled, taking Harry and his younger brother, Dennis, with her. She sometimes passed as Irish or Spanish to get decent apartments, and changed their last name at least twice, while evading immigration authorities.

Against his mother’s wishes, Belafonte dropped out of high school, worked odd jobs, and eventually enlisted for WWII service in a very segregated United States Navy. He emerged from the Navy in 1945, with an even more curious mind and an ambition to learn. Those early years would help shape the young Belafonte’s political ideology, as he devoured the writings of civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois, while developing a respect for labor unionist, civil rights activist, and socialist A. Philip Randolph. Belafonte’s political beliefs were also greatly inspired by the singer, actor and Communist activist Paul Robeson, who would later become a mentor.

Belafonte chose to study acting on the G.I. Bill and would soon meet an eager Sidney Poitier, as both men were members of the American Negro Theatre in Harlem before it closed in 1949. They bonded over a mutual love of cinema, and would maintain that connection throughout their lives. Belafonte would later transfer to the New School’s Dramatic Workshop in the late 1940s, where his classmates included Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Bea Arthur, Elaine Stritch, and Rod Steiger, also early in their careers.

During those years, Belafonte discovered New York’s jazz scene. The city had become the music genre’s epicenter, and Belafonte routinely hung around jazz clubs, notably the Royal Roost in Manhattan’s Theater District, curious about this dominant style of music. Roost regular, saxophonist Lester Young, encouraged him to sing, and soon enough, he did. On his first outing at the Roost, Belafonte was backed by a band comprised of artists who would go on to become highly influential themselves, including drummer and composer Max Roach, saxophonist Charlie Parker, and pianist Al Haig.

He became a regular, winning over audiences with his soft melodic voice and performing many jazz standards. However, the exclusivity of jazz, which found him playing in front of mostly white audiences, didn’t suit Belafonte, who felt the need to connect with the struggles of everyday people.

“Listening to the voices of those who sang out against the Ku Klux Klan, and out against segregation, and women, who were the most oppressed of all, rising to the occasion to protest against their conditions, became the arena where my first songs were to emerge,” Belafonte wrote in his memoir.

At the Library of Congress, he discovered and studied the folk songs collected by Alan Lomax, a musicologist credited with bringing prominent folk, blues and protest musicians to a wider audience. Lomax’s repertoire included Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Lead Belly. Soon, Belafonte was singing folk songs at union rallies, and to raise money for civil rights causes.

The song that would become his breakthrough was a nod to his Caribbean roots; in 1956, he recorded “The Banana Boat Song,” with its “day-O” refrain. A reworking of a traditional work song created by Jamaican dock laborers who loaded shipping vessels with bananas, it became Belafonte’s signature for much of his career.

It was a prosperous decade for Belafonte, whose music career was thriving. It was also his most prolific period as an actor. His first film role was in the drama “Bright Road” (1953), in which he was introduced to Dorothy Dandridge in her first lead role. The two subsequently starred in Otto Preminger’s hit musical “Carmen Jones” (1954). A year later, he co-starred in the original Broadway production of the musical, “3 for Tonight” (1955).

With Sidney Poitier as his only real competition for lead roles for Black male actors, Belafonte was subsequently allowed to take on parts that were seen as controversial at the time, including playing one-half of an interracial romance in 1957’s “Island in the Sun,” opposite Joan Fontaine. As was common practice at the time, in order to appease prickly white audiences, the most the two shared together on screen amounted to intense stares.

Generally, Belafonte was dissatisfied with much of what he was offered, including the male leads in “Lilies of the Field” (1963) and “To Sir With Love” (1967), which he rejected because he felt the characters were “neutered.” (Poitier replaced him in both.) Belafonte was also offered the role of Porgy in Otto Preminger’s “Porgy and Bess” (1959), where he would have once again starred opposite Dandridge (as Bess), but he passed on the role because he objected to its racial stereotyping.

Meanwhile, Belafonte’s accomplishments at the time included becoming the first solo singer (of any race) to have an album sell over a million copies with “Calypso,” in 1956. He would also become the first African American to win an Emmy for “Tonight With Belafonte,” in 1959.

In response, he launched his own production company, HarBel Productions, under which he starred in and produced films like Robert Wise’s “Odds Against Tomorrow” (1959), in which he played a bank robber teamed with a racist partner (Robert Ryan) to pull off a heist. HarBel also produced the post-apocalyptic drama “The World, the Flesh, and the Devil” (1959), in which Belafonte co-starred with Inger Stevens. Still, even with a modicum of control, the film–Belafonte’s highest payday (including a percentage of the profits) as an actor–muted his character’s agency and sexuality.

The decades that followed saw his commitment to acting gradually supplanted by his social and political activism (as well as a lucrative music career, where he found far more freedom). He drew inspiration from his mentor Paul Robeson, who stood in firm opposition to not only racial prejudice in the United States, but also colonialism in Africa. And just like Robeson, along with other civil rights activists during the “Second Red Scare” of the 1940s and 50s, Belafonte was frequently targeted for allegedly conspiring with communists, although those investigations ultimately led nowhere.

In 1956, as Belafonte’s entertainment career blossomed, with “Day-O” at No. 1 on the Billboard chart for 31 weeks, he received a phone call from a young Martin Luther King Jr. At the time, King was known for the Montgomery bus boycott (1955-56), which began when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white person. King wanted to bring national attention to a burgeoning civil rights movement, and thought an entertainer of Belafonte’s growing stature and temperament might help.

It was a pivotal year for the 29-year-old Belafonte–as well as a truly wondrous, but also precarious time for Black artists, especially those who insisted on being outspoken. He was struck by King’s sense of calm, humility, and determination to accomplish what he saw as his mission, and he was inspired by King’s leadership, and supported King’s efforts until his assassination in 1968.

Ultimately, King and the movement gave Belafonte’s life ballast, as he became a key figure in the civil rights movement who was directly involved in almost every related cause, from organizing to fundraising efforts alike. These included Mississippi Freedom Summer voter registration drives, which provided bail money for King and other arrested civil rights protesters; bankrolling the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); backing the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech; the cultural boycott of apartheid-era South Africa, and the 1985 charity fundraiser global hit song, “We Are the World.” Belafonte also provided for King’s family financially, since the leader made roughly $6,000 a year as a preacher.

Belafonte’s activism continued into the next century: He called out the George W. Bush administration in the early 2000s, for the Iraq war. And even when it was very unpopular to do so, he rebuked the Obama administration for what he saw as its lack of courage in tackling social ills, especially rising, devastating poverty levels.

The 1960s were spent primarily on activist causes and his music. Invited by Johnny Carson, Belafonte guest-hosted “The Tonight Show” for a week in February 1968, featuring an eclectic guest list that included King, Robert F. Kennedy, Lena Horne, Bill Cosby, Wilt Chamberlain, Marianne Moore and Zero Mostel.

In the 1970s, Belafonte did start to appear in more films, although very few. Highlights included the western “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), and the action-comedy “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), both with Poitier. And in 1984, he produced the musical drama “Beat Street,” which explored New York City’s burgeoning hip-hop scene.

The remainder of his acting career was scattershot, as he primarily took on supporting or peripheral roles in both independent and studio films, including John Travolta in the drama “White Man’s Burden” (1995) and in Robert Altman’s jazz age-set “Kansas City” (1996), for which he was awarded the New York Film Critics Circle trophy for Best Supporting Actor. And in 2006, Belafonte appeared in “Bobby,” Emilio Estevez’s ensemble drama about the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, in which he played Nelson, a friend of an employee of the Ambassador Hotel (Anthony Hopkins). His last screen appearance was in Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman” (2018) more or less playing himself as an elderly civil rights pioneer.

Belafonte stopped singing in 2004 due to longstanding issues with his vocal cords, which began when he had nodes removed in the 1950s. It was a significant moment for a performer whose singing shaped a country’s musical consciousness. “I believe my time was a remarkable one,” Belafonte wrote in “My Song.”

I am aware that we now live in a world overrun by cruelty and destruction, and our earth disintegrates and our spirits numb, we lose moral purpose and creative vision. But still I must believe, as I always have, that our best times lie ahead, and that in the final analysis, along the way we shall be comforted by one another. That is my song.

In 2020, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture acquired Belafonte’s vast personal archive, which includes photographs, recordings, films, letters, artwork, and much more, which serve as documentation of his career as an musician and actor, and maybe most importantly, as an activist, who crossed paths, at one time or another, with a veritable who’s who of the entertainment and political spaces, from Paul Robeson, Sidney Poitier, Bob Dylan, Frank Sinatra and Marlon Brando, to Eleanor Roosevelt, Martin Luther King Jr., the Kennedys, Fidel Castro and Nelson Mandela, to name just a few.

He is survived by his wife, Pamela Frank, four children, and two step-children.